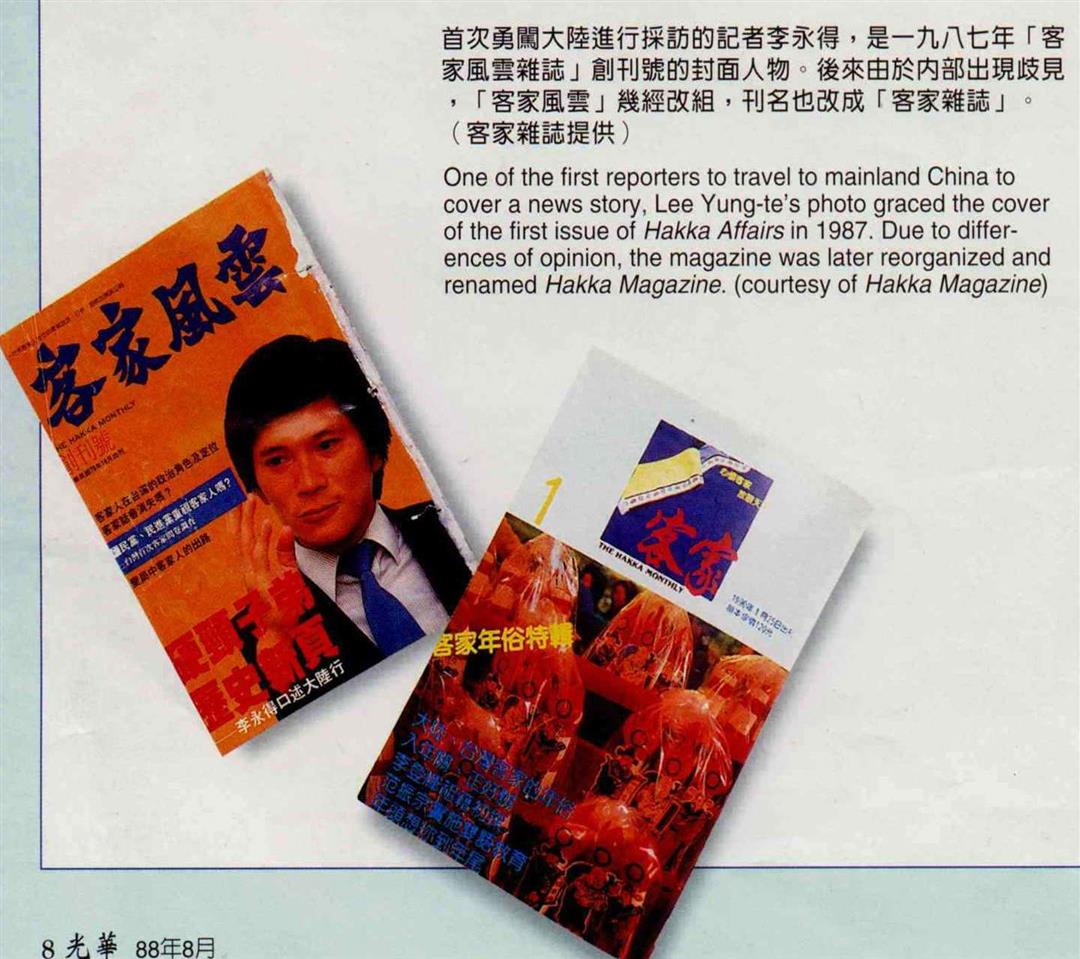

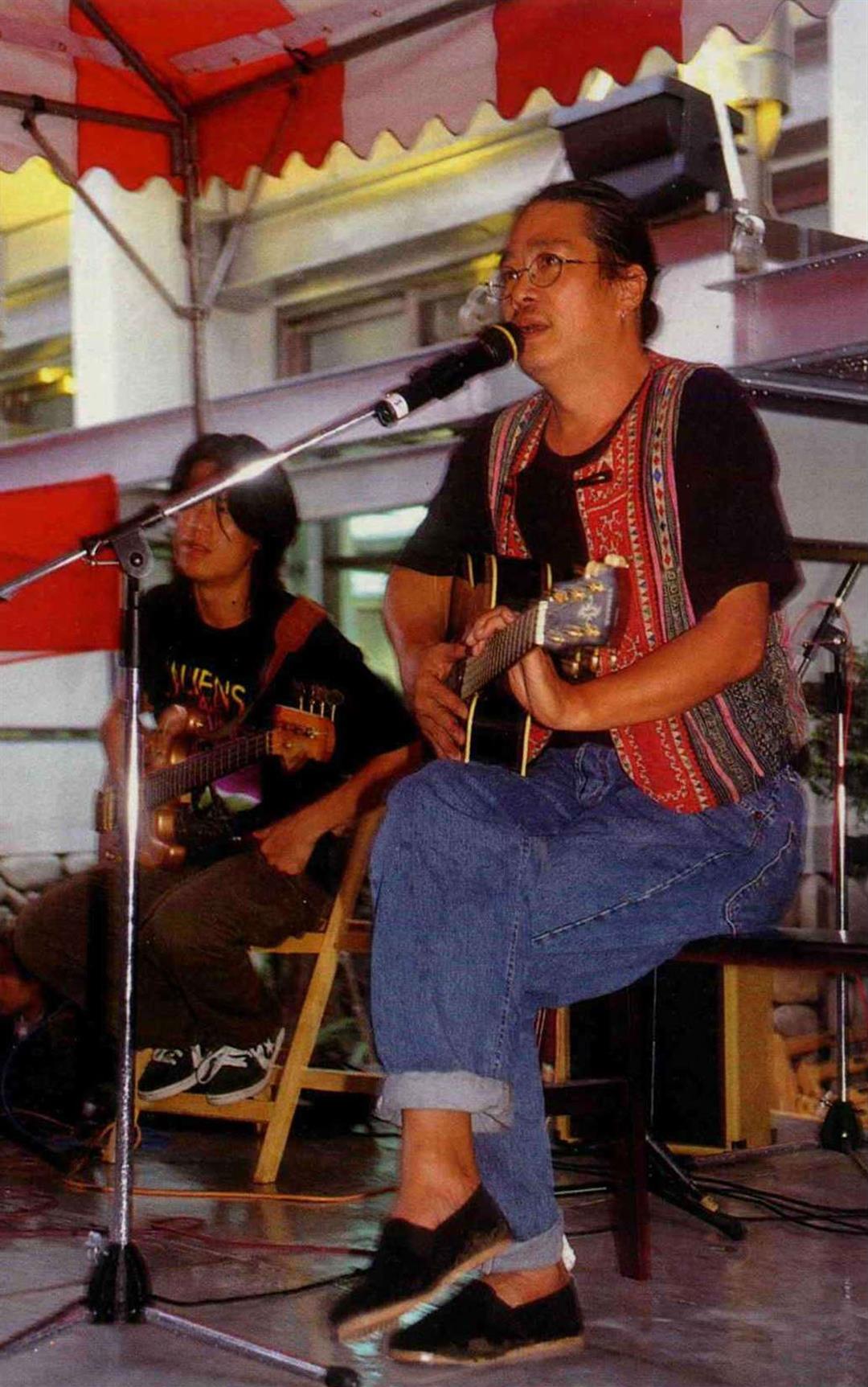

One of the first reporters to travel to mainland China to cover a news story, Lee Yung-te's photo graced the cover of the first issue of Hakka Affairs in 1987. Due to differences of opinion, the magazine was later reorganized and renamed Hakka Magazine. (courtesy of Hakka Magazine)

When you hear the word "Hakka," what comes to mind? Heavyweight politicians like Wu Poh-hsiung and Hsu Hsin-liang? Mountain folk songs? Or maybe the bantiao (broad-rice noodles) and kejia xiao chao (simple stir-fry dishes) that they serve at Hakka restaurants?

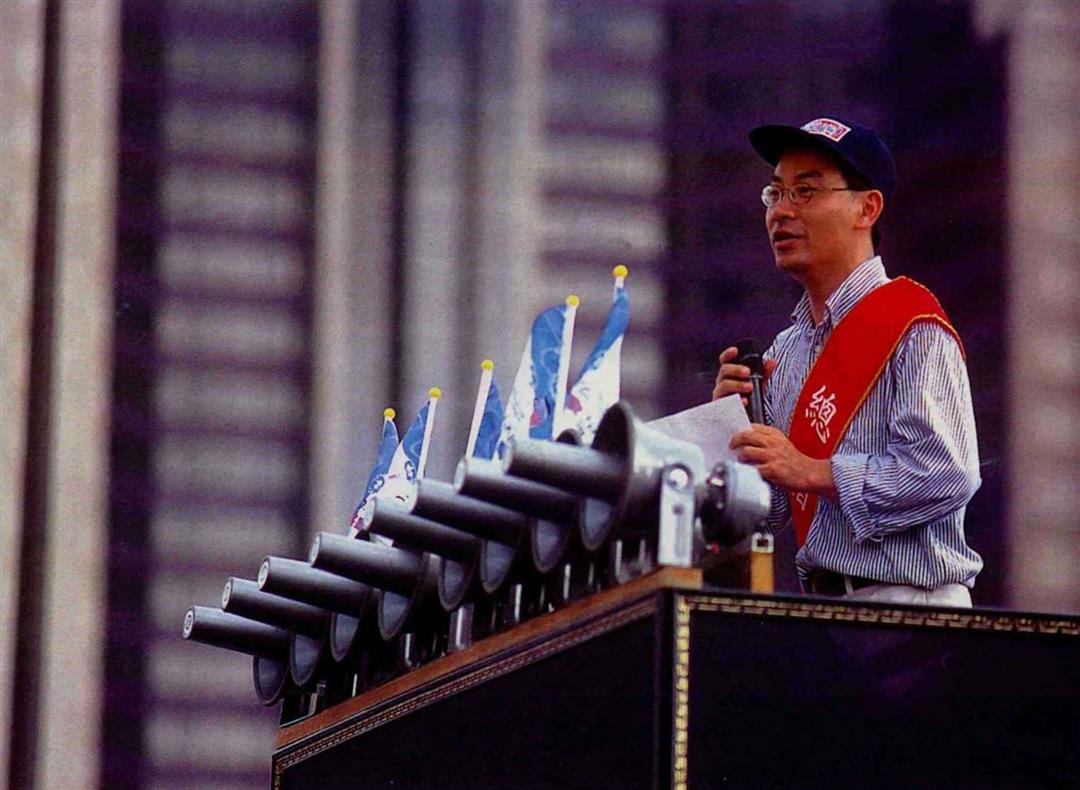

Hugh Lin, director of the Taipei City Government's Bureau of Civil Affairs, is recognized as Taiwan's youngest government official. As a Hakka, Lin couldn't help but feel of welter of conflicting emotions when he helped organize a street march seeking greater visibility for the Hakkas.

The Hakkas, who number more than four million in Taiwan, are the island's second largest ethnic group after the Fujianese. Odd as it may seem, however, it's not likely that you'll ever hear Hakka language or Hakka songs outside of traditional Hakka towns. Hardly any non-Hakkas even know how to say hello in Hakka. Even the Hakkas themselves learn to camouflage their ethnic identity when they move to a big city. Although the movement to improve the social status of the Hakka community has been going on for more than a decade now, the theme of this year's Hakka culture festival in Taipei is still "greater visibility for the Hakkas."

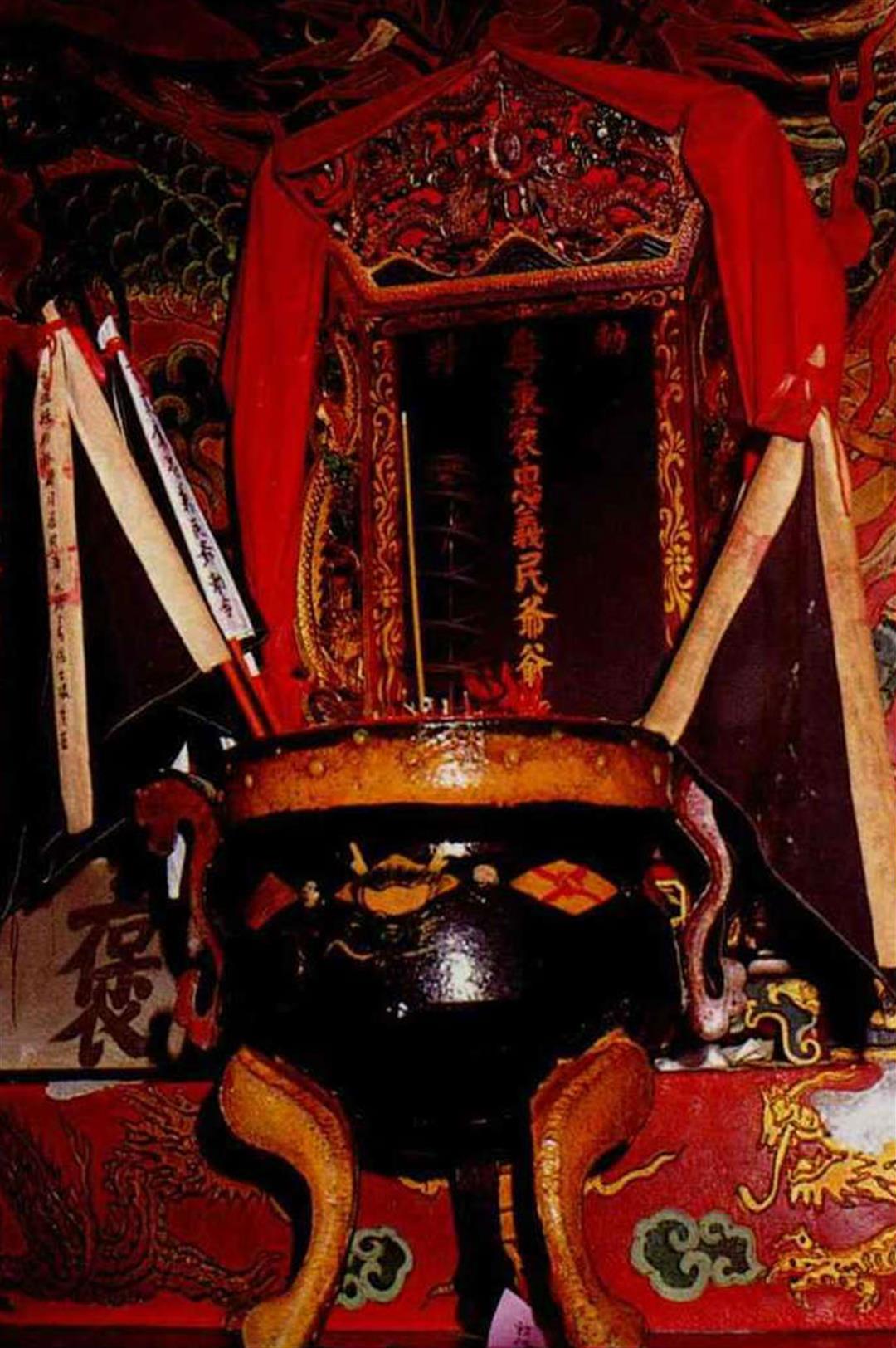

Yimin Temple ("militiamen's temple") in the township of Meinung (Kaohsiung County) has a statuary niche and a carved wooden memorial dedicated to volunteer militia who were killed in battle and later lauded by the Qing dynasty rulers for helping in the fight against rebels. Worship of the spirits of these militiamen is a distinctive feature of Taiwanese Hakka religion. They don't worship idols at this temple. What they worship is the fight-to-the-death spirit of the militiamen who gave their lives in defense of their hometown.

How should Hakkas go about achieving greater visibility? And how should other ethnic groups show concern for the Hakkas? What do we have to do to understand their feelings, and their turbulent past?

Just before the opening of this year's Hakka culture festival, a press conference was called by the festival's organizer, the Taipei City Government's Bureau of Civil Affairs. The press conference was a disaster. They mainly spoke Hakka, and lots of reporters stormed out in anger. Cries of protest arose: "What's the big idea. I can't understand a thing. I'm out of here!" "So you Hakkas are chauvinists too, huh?" Newspaper reporter Chang Wen-hsiung stood up, but didn't say anything. He was confused about something-all these same people had previously attended press conferences where nothing but Taiwanese was spoken, and while some people couldn't really understand it very well, hadn't everyone given it their best shot? Now they had come to the Hakka community center and the Hakka language was being used to discuss Hakka-related matters. Moreover, the organizers had even gone to the trouble of providing interpreting into Mandarin. So why did everyone raise such a big stink?

There was still another question that disturbed Chang more than anything else: "If others aren't interested in Hakka affairs, that's no problem, but why should I, a Hakka myself, be expected to storm out with everybody else?" Having grown up in Taipei, Chang doesn't actually speak a word of Hakka and has never felt any sense of identification with the Hakka community. Under the circumstances, however, he felt terrible about the insult to the Hakkas that day, and his own feckless reaction to it. All of a sudden, he got the desire to understand his people. "Perhaps," thought Chang, "I should take the day off tomorrow and go visit grandmother in Pingtung. I could learn a few Hakka phrases."

The above is historical fiction. The debacle at the Hakka press conference really happened, but the rest is the idea for a play that Chen Ming-jen thought up after he learned about the incident. Chen is an active participant in the movement to improve the status of the Taiwanese language. A number of similar incidents have shown that the movement to raise public consciousness about the Hakka community has made little headway since it started more than a decade ago, even though the government clearly attaches importance to the issue.

They don't worship idols at this temple. What they worship is the fight-to-the-death spirit of the militiamen who gave their lives in defense of their hometown.

Is the best behind them?

The lifting of martial law in 1987 marked the beginning of movements to promote greater democracy and allow greater visibility for facets of culture that are purely Taiwanese in character. The democracy activists demanded an end to "the monopoly on power by authoritarians not born in Taiwan," and a "Hakka movement" was launched by people seeking to protect the interests of the Hakka community.

Hakka Affairs was launched in 1987 and sounded the call for Hakkas to take pride in their ethnic identity. In 1988 Hakkas organized a 10,000-person march in Taipei under the banner "Give us back our native tongue!" Big-city Hakkas have a reputation for being docile and invisible; this was the first time they had ever taken to the streets to show their clout. On the momentum built up by the big street march, Hakkas established Hakka-language TV and radio stations. Various Hakka organizations were also founded, and Hakkas in the academic community began releasing studies on Hakka issues. Taiwan's four million Hakkas began to attract attention.

However, the Hakka movement has always seemed somewhat limited. Today, more than a decade into the post-martial law period, the other two main pre-1945 ethnic groups (the indigenous tribes and the Fujianese) have both achieved quite a bit through ethnic movements launched at the same time as the Hakka movement. These other groups have basically established themselves as the two main representatives of the island-based portion of Taiwanese culture. The Hakkas, on the other hand, still have the same low profile as before. Even many middle-class Hakkas have lost their enthusiasm for the Hakka movement, which is plagued by a sense of frustration and powerlessness. Why should this be?

One of the first chief editors of Hakka Affairs, Yang Chang-chen, now acts as legislative assistant for the prominent Hakka legislator Yeh Chu-lan, and has practically grown up with the Hakka movement. According to Yang, the Hakka movement originally got started in response to calls from people involved in the democracy and native-culture movements, but in a democracy, the majority rules. The success of the democracy movement enabled the Fujianese, who account for 70% of the Taiwanese population, to quickly establish themselves as the masters of the island. Fujianese are "the Taiwanese," and the Minnan (southern Fujian) language is called "Taiwanese." In other words, the authoritarian regime from across the strait may be a thing of the past, but now it's the Fujianese majority that has a stranglehold on power in Taiwan. Nothing has gotten any better for the Hakkas.

Taiwan's indigenous tribes, on the other hand, have done very well for themselves in the native-culture movement in spite of the fact that their population only comes to about 400,000. Not only have the leaders of the indigenous tribes worked vigorously to protect their interests, but they have even been joined in the effort by many Han Chinese, who perhaps feel a need to "atone for their guilt" as representatives of an invading race. Books, records, and TV shows on indigenous philosophy and art have become a market staple in Taiwan, and the Executive Yuan has established the Council of Aboriginal Affairs, which works to help indigenous peoples get a fair shake in terms of medical care, education, job opportunities, and the like.

The economy of a traditional Hakka village is based primarily on such cash crops as tea leaves, fruits, and betel nuts. The women in this picture are picking tobacco leaves and preparing to take them in for curing.

Caught in no-man's land

Yang Chang-chen emphasizes that he has absolutely no objection to the dominant position of the Fujianese; they are the majority, and their predominance is only natural. Nor does he have any complaint with the special treatment received by the indigenous peoples; they are in a very disadvantaged position, and need a helping hand. What he does find regrettable, however, is that no one is interested at all in the one simple request that the Hakkas are making-a request for a measure of respect and equality, and a feeling of mutual understanding and appreciation between different ethnic groups. These things could be achieved without spending huge sums of money, but no one seems to be listening.

Huang Tzu-jao, general secretary of the Taiwan Hakka Affairs Association, describes the Hakkas as being lost in a no-man's land. The Hakkas are not few enough in number to elicit sympathy, but neither are they great enough in number to be mainstream. Hakka culture is not yet on the verge of extinction, but it cannot quite settle in and grow, either. There are barriers which make it difficult for Hakka society to flourish, but it is impossible to say just how it is being held down, or by whom. This "neither/nor" predicament has left the Hakkas high and dry, without support from any quarter. At a time when other groups have achieved heightened visibility and have succeeded in winning general acceptance of their need to preserve their rights, the Hakkas are still saddled with the same old stereotypes they've always had to live with-invisible, docile, conservative, impassive. . . . Hakka activists have to take to the street to get their own people to adopt a bit of a higher profile.

A quick glance at the ranks of society's post-martial law political and business leaders is revealing. Even though the Hakkas account for nearly 20% of the population of Taiwan, Hakkas seldom hold cabinet-level posts in the government, and Hakka firms are scarcely represented among the island's top 500 corporations. Hakkas are very worried by the sense that their culture is rapidly disappearing, and feel deeply affronted by an unequal distribution of political and economic power. So why don't these worries spark a vigorous response?

Tunghua Street is a major Hakka enclave in Taipei. Most of the businesses here are small shops. Mr. Chang, who runs a bicycle shop, has lived here for over 20 years.

Meek as a mouse, or heart of a lion?

Ideology is the foundation of all social movements. For the Hakka movement, it is the first stumbling block.

One must start by answering the question: What exactly does the term "Hakka" mean? Hsu Cheng-kuang, director of Academia Sinica's Institute of Ethnology, is a Hakka from the town of Neipu, in Pingtung County. He notes that there are many conflicting ideas about where the Hakkas originated, and that this question continues to be a riddle in the academic community. According to the most generally accepted definition, however, Hakkas are any member of a group of mountain dwellers who lived for many generations in an area where the provinces of Jiangxi, Fujian, and Guangdong come together.

When these mountain people interacted with lowland inhabitants, it often led to disputes between the two groups. The lowlanders have many pejorative terms for the Hakkas-rednecks, hicks, and other names. The early 20th century Hakka scholar Luo Hsiang-lin conducted a search for the roots of the Hakka people, and concluded that the Hakkas descended from nobility who had fled to southern China long ago from the Yellow River region. Luo argued that the purest of all Han Chinese blood was to be found in the veins of the Hakka people. This idea quickly caught on among Hakkas, and has today achieved the status of gospel. The names of many Hakka organizations today reflect this belief.

Since the lifting of martial law, however, this Han connection has lost it cachet. The emphasis now is on things Taiwanese. Says Yang Chang-chen, "As we came to accept such ideas as 'Taiwan first' and 'our Taiwanese identity,' people with a mainland Chinese identity came to be seen as the cat's-paws for the unjust rule of non-Taiwanese. All of a sudden they were dastardly characters who worked to suppress native Taiwanese culture. These people were to be thrown out of power." Unfortunately for the Hakkas, an identity that they had finally grown to embrace became a cause for consternation. Every Hakka had to ask: "If I don't want to be the representative of the Han Chinese, then what should I be?"

In the midst of a rapidly changing social environment, some Hakkas have begun to ridicule the "spirit of loyalty and righteousness" that has long been the pride of their people, choosing instead to stress a rebellious nature and fighting spirit. Some Taiwanese Hakkas are even unwilling to talk about Hakka worship of the spirits of the yimin militiamen, who died some 200 years ago fighting against Taiwanese rebels who had been seeking to overthrow the Qing dynasty. This identity shift has not been universally accepted in the Hakka community, however; on the contrary, it has led to considerable disagreement and conflict.

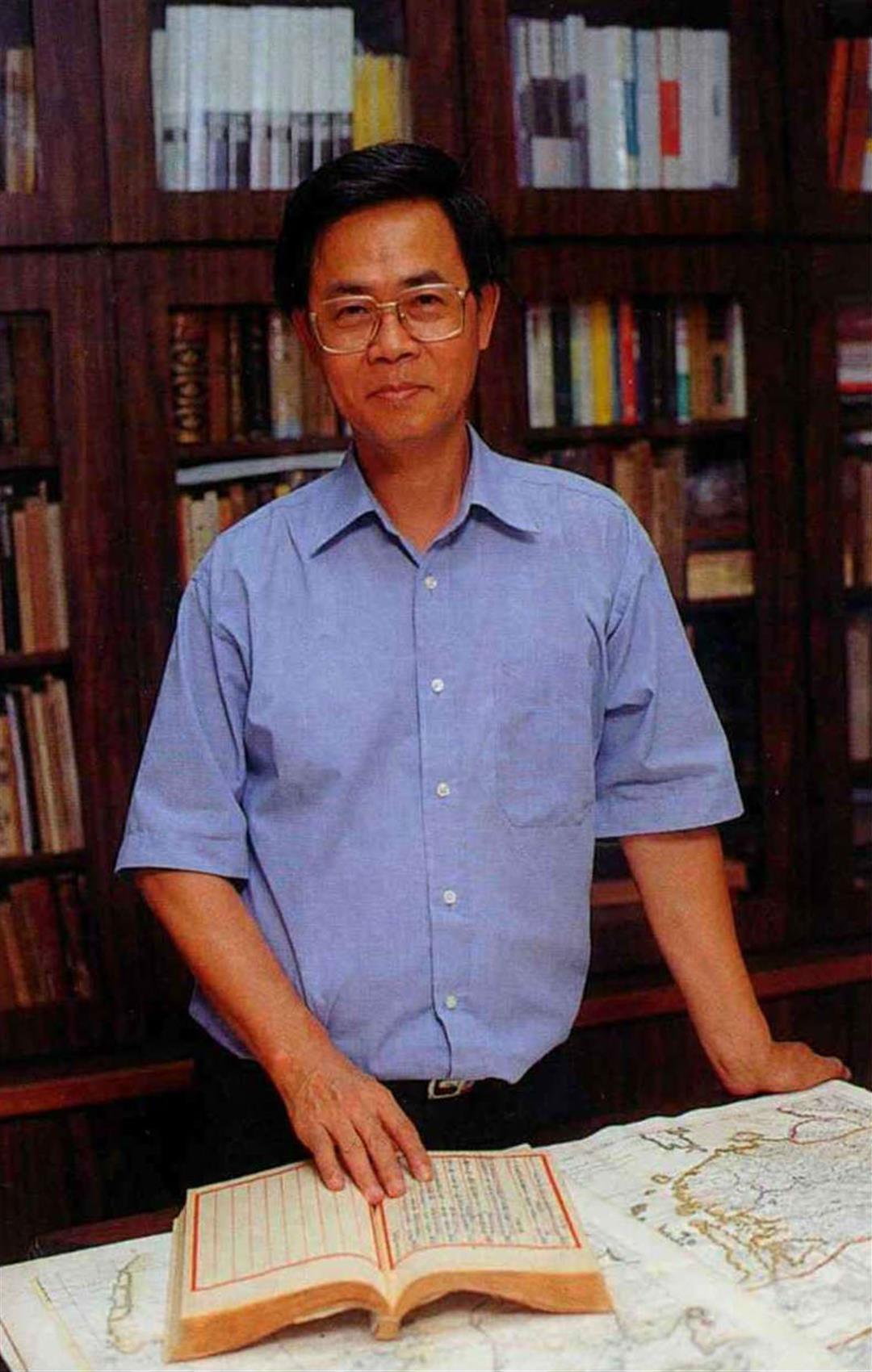

There are many Hakkas engaged in the publishing industry. Wei Te-wen, of SMC Publishing Inc., has won widespread respect in the industry with a series of books on Taiwan history.

Home is where the heart is

Hugh Lin, director the Taipei City Government's Bureau of Civil Affairs, is a long-time social activist. As a Hakka, he has his own interpretation of the distress generated by the question of Hakka identity. According to Lin, the Hakka identity has never been linked to any particular place; rather, it transcends local and national boundaries. Many mainlanders from Jiangxi, Sichuan, Guangdong, Fujian and elsewhere are 100% Hakka in both lineage and culture. In the huge Hakka enclaves of Malaysia, the phrase "I'm Hakka" is a declaration of identity, and a key that opens the door to participation in Hakka society. The same holds true wherever Hakkas congregate, be it Tahiti, Calcutta. . . .

"For a Taiwanese Hakka," says Yang, "the Hakka community itself is their homeland. For Taiwanese of Fujian extraction, however, their homeland is Taiwan." The Fujianese have thrown off their emotional ties to Fujian Province and declared, "I am Taiwanese." The Hakkas, on the other hand, are uncertain about whether they wish to declare, "I am a Taiwanese Hakka."

Also, while the Fujianese have dived ebulliently into the "Taiwan first" movement with a sense that "what's good for us is good for Taiwan," the Hakkas have never gotten over their "vagabond" mentality; they can't quite see themselves as masters of this island.

To the outsider, the Hakka movement has been pursued in great moderation, and when the Hakkas seek to get what they feel is a fair shake, they always dress up their demands in high-sounding rhetoric. They stress, for example, that "the Hakka movement isn't just for the Hakkas, but seeks equality between all ethnic groups." Another oft-heard idea is that "when we speak of Hakkas, we do so not as Hakkas, but as Taiwanese. We are an asset to Taiwan, and ought to be valued by everyone as such." This all is very enlightened and visionary, but it is a tepid way to carry out the Hakka movement.

The historical background of the Hakkas has also done much to mold the character of the Hakkas as a community. Huang Tzu-jao points to the migratory experience of the Hakkas over the past millennium as a major determinant in this regard. Because the Hakkas generally arrived later than their counterparts from Fujian, says Huang, or because they were outnumbered by the latter, they couldn't hold their own in the rich plains, but had to carve out a niche for themselves in the surrounding foothills, where they engaged in agriculture.

Wherever they have congregated-the mountains of southern Jiangxi Province, Mei County in Guangdong, the outskirts of Chengdu in Sichuan Province, or the counties of Taoyuan, Hsinchu, Miaoli, and Pingtung-the Hakkas have never lived in big cities, thus their communities have never developed to a high level of political, economic, or cultural prominence. Their historical role as farmers has left the average Hakka outside the loop in business and politics. In politics, they have not had the resources or savvy to get involved. In business, they have lacked the confidence to start up big ventures.

Chen Yung tao attracted a lot of attention this year when he released a Hakka rock album with a very modern sound. However, lots of Hakkas still like to recharge their spiritual batteries by attending schools where they learn traditional Hakka folk songs.

On the comeback trail

Fan Yang-sung, general manager of a local management consulting firm, has spent a lot of time studying the relationship between business firms and ethnicity. He mentions several reasons for the predominance of Fujianese in the business world. The Fujianese have ruled the roost in the plains for several centuries. During this time, the highly profitable agriculture of the plains has enabled them to build up a strong base of capital. At the same time, their experience in the markets of the plains has enabled them to hone their business skills. As for the mainlanders who came to Taiwan after 1945, although they are a minority, they brought with them the brash confidence of ones who have a special connection to the rulers. What is more, the "Shandong capitalists" and the "Shanghai capitalists" both arrived with a wealth of business experience and personnel resources at their disposal. They stayed right at the top of the business world after coming to Taiwan.

Hakka business activities have been minuscule in comparison. Among the 500 largest corporations in Taiwan today, there are barely any owned by Hakka capital, and among the leaders of industrial associations, the proportion of Hakkas comes nowhere close to reflecting the fact that Hakkas make up nearly 20% of Taiwan's total population. All these facts show the impact of historical factors.

Fan Yang-sung also notes that centuries of grinding poverty have made the Hakkas cautious and conservative. They are very averse to taking risks. Current statistics show that while no Hakkas are fabulously wealthy, as a group they are solidly middle class. A conservative, worry-wart nature is deeply ingrained into the Hakka character.

Fan's own experience as a businessman is a good illustration of this phenomenon. When he first quit his steady job with the government and set up his own company, his family was strongly against it, and relations were quite strained for a time. Even now, every time he visits his parents in Hsinchu, they always have advice for him: "Sell your company! Don't get too mixed up with banks! Don't borrow too much!"

The business behavior of Hakkas, says Fan, contrasts starkly with that of the Fujianese as well as the second-generation mainlanders who grew up in Taiwan's many military housing complexes. Even though the families of second-generation mainlanders generally have no land or assets, these people still dare to try their luck in the business world. Fujianese, in the meantime, have family wealth and personal connections that Fan can only admire with a sigh. The situation with Hakkas, on the other hand, is totally different. They are caught in a vicious cycle-poverty makes them insecure; insecurity makes it difficult for them to succeed in business; difficulty in business makes them all the more insecure. . . . On top of that, the Hakkas have a long tradition of "banding together to defend against outsiders." As a result, the Hakkas are not good at bargaining or creating alliances with outside groups. This has made it difficult for them to reap the benefits of strategic tie-ups or the trend toward global operations.

From an outsider's perspective, the Hakkas appear to be a very cohesive group, and not highly open to non-Hakkas, but it is worth noting the words of Hakka political leader Wu Poh-hsiung, a senior advisor to President Lee Teng-hui. Wu himself runs a family enterprise, and he expresses frustration with the conservative, cautious nature of his own Hakka people, who "insist on getting involved in the management of any business they put their money into." The Hakkas are very skittish about placing their money in the hands of others, says Wu, and even when good friends pool their resources to run a business, the business often folds amidst disputes, with everyone disagreeing on its management. In today's world, businesses must adopt modern, systematic management practices, but Hakka business owners are usually unable to let their businesses grow very large because they are unwilling to trust professional management.

Is the Hakka movement actually making any impact? Where to go from here?

Taiwanese spoken here

Hakkas tend to take a low profile because of their weak economic status. Ability to speak Mandarin is something everyone needs in Taiwan, of course, but most Hakkas who do business in urban areas also learn to speak fluent Taiwanese in order to communicate with customers and, even more importantly, to hide their Hakka identity and avoid discrimination.

Even in predominantly Hakka towns, there is a deeply ingrained concept that "if you want to go into business, you have to speak Taiwanese." The city of Chungli in Taoyuan County, for example, has over 200,000 Hakka residents, and is acknowledged as the largest urban concentration of Hakkas in Taiwan. Take a stroll in Chungli, however, and what languages do you hear? Mandarin and Taiwanese. In fact, you might even run across a few Southeast Asian laborers speaking Thai or Tagalog. What you won't hear is Hakka.

This reporter jumped into a taxi and asked the driver, a man in his 50s who spoke perfect Taiwanese, why he would choose to go looking for work in a Hakka city like Chungli. He sheepishly explained that he was actually a Hakka from the local area.

Explains the driver (Wu Kui-hsin): "We Hakkas are the majority here, it is true, and we have a lot of money, but we don't like to go into business. We prefer to rent our business property on the main streets to Fujianese outsiders. We just collect rent." Over the years, all the stores have come to be run by Fujianese, and Taiwanese has become the language of business. Taxi drivers like Wu naturally take to speaking Taiwanese. Sometimes he will pick up riders that he knows perfectly well are Hakkas, but he still speaks Taiwanese with them, and it even feels quite natural to do so. His linguistic situation is even crazier at home-both he and his wife are Hakka, but they speak different Hakka dialects, so they prefer Taiwanese! Their children can only speak Taiwanese.

Where do they speak Hakka?

Traditional Hakkas are not adept at politics or business, which would seem to put them at odds with the spirit of modern city life.

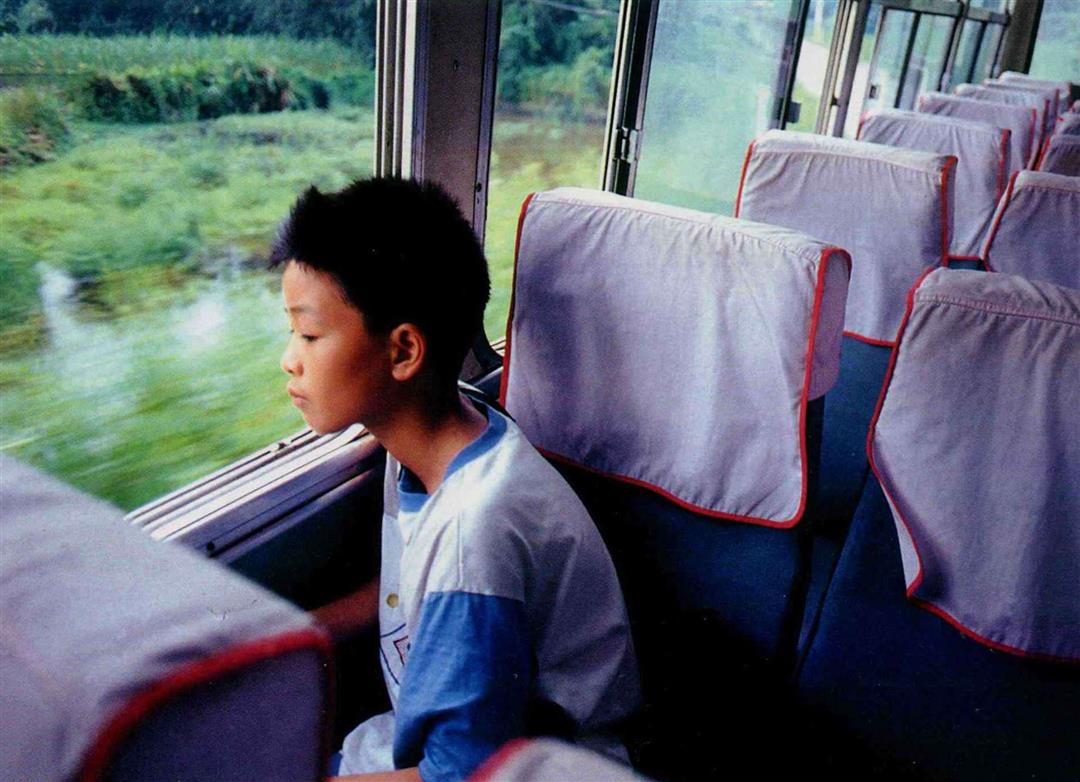

Hsu Yu-ling, a student at Kaohsiung Medical College, grew up in a Hakka town in Miaoli County. She indicates that although the younger generation does not speak Hakka as often as older people do, you can still hear Hakka spoken on the streets, and at weddings and other festive occasions someone will always start singing Hakka folk songs. She does not feel that Hakka culture is in danger of disappearing. At the same time, however, she has not had the opportunity to speak Hakka since coming to Kaohsiung, and there is no place in this big city where she can go to get in touch with her Hakka roots. She feels a lot like a tiny creek that has suddenly flowed into a big ocean-all sense of the creek is quickly disappearing into the vast expanse of sea.

Yu-ling's junior high classmate, Kao Wei-tang, now serves as president of the Hakka students' club at Taipei Medical College. He recognizes Yu-ling's experience as a familiar one. When Hakka students who have been in Taipei for a long time get together, they always speak in Mandarin. Why? Says Kao: "I don't know. No one takes the lead in speaking Hakka. Maybe everybody would feel strange speaking Hakka in Taipei." The Hakka movement calls upon Hakkas to speak more Hakka in public places, and to use Hakka more often even when discussing things not directly related `to home life, but the psychological barriers are formidable.

The Ministry of Education recently adopted a plan to require elementary and junior high school students to study one of Taiwan's non-Mandarin languages (students will choose between Taiwanese, Hakka, and the various indigenous languages), but Li Yung-chi, a professor of history at National Taiwan University, has reservations about the effectiveness of this idea in spite of the fact that he himself is a Hakka who was involved in getting the Ministry of Education to adopt this plan. He bluntly points out that there are many concepts and situations that are difficult to discuss in Hakka, and there are not so many qualified teachers or teaching materials. Li indicates that he would not be opposed if his children decided to study Taiwanese rather than Hakka.

Cream of the crop

It must be stressed, however, that the underprivileged state of the Hakkas as a group does not mean that Hakkas are incapable of individual success. In fact, the Hakkas are noted for their diligence and love of learning. High-ranking Hakkas are to be found in large numbers in all walks of life, including government, business, academia, and the media.

Academia Sinica's Hsu Cheng-kuang points out that the Chinese people attach great value to education, and this is especially true of the Hakkas, who have been called the "Jews of East Asia." With the doors to the elite circles of politics and business virtually closed, Hakkas generally take advantage of every opportunity the government provides to ensure that their children develop into intellectuals. Hakkas parlay knowledge and skills into high-level jobs, and with the hard-working nature for which they are so well known, their bosses typically come to rely heavily upon them. They take the low-profile path to success-no need to vie for the top spot or take risks.

Activists in the Hakka movement criticize this type of behavior, saying that it seeks assimilation into the mainstream at the cost of lower visibility for the Hakkas as an ethnic group, but Hsu Cheng-kuang argues that this is a path that Hakkas have chosen for themselves on the basis of a sober assessment of Taiwanese society. In Hsu's opinion, this path has brought the Hakkas success, and is most in line with Hakka interests.

In recent years, Hakkas have gradually come to realize that economic power is the invisible hand that controls everything. Says Fan Yang-sung, "Economic power is what determines a culture's ability to survive. The economic base determines the direction of government policy." For this reason, the Hakka movement has gradually shifted its focus from the government to the private sector, and from cultural and linguistic preservation to the development of economic power.

The new theme of the Hakka movement is "creating a sense that Hakka culture is a valuable thing." The role of the media is an oft-discussed topic in this regard, for Hakkas do not receive anywhere near the degree of media exposure that their share of the population would seem to merit. Hakka activists have always concentrated on demanding more Hakka-language TV programming and more reporting of Hakka news.

Surprisingly enough, however, a look at the ethnic makeup of the mass media reveals that Hakkas are anything but a disadvantaged minority. In fact, they have quite a bit of clout. The president of the Chinese-language China Times is Hakka, as are the general managers of Formosa TV, Public Television, and China Television (CTV), not to mention the owners of many publishing houses. These people adhere strictly to professional standards on the job, however, and do not attempt to use their positions to create higher visibility for the Hakka community. Hakkas are actually quite numerous, and they wield a good deal of power, but their reluctance to assume a high profile is demonstrated quite clearly in the mass media.

Looking for that "star quality"

Lee Yung-te, acting president of the Public Television Service Foundation, has a thing or two say on the relationship between Hakkas and the media. As a Hakka from the township of Meinung, he recently took a barrage of criticism from his hometown friends and acquaintances on account of the fact that Hakka programming only accounts for 0.2% of total programming at Public Television. He points out that Hakkas already have their own TV station, and that there are two Hakka satellite channels in the greater Taipei metropolitan area. Furthermore, commercial television stations such as Formosa TV have stepped up their proportion of Hakka programming. Lee Yung-te, however, questions the usefulness of these measures, and asks what difference the existence of Hakka mass media makes when Hakkas themselves do not watch Hakka programs, listen to Hakka radio, or read Hakka magazines.

Lee stresses that in a world where the profit motive is king and commerce is dominated by a chase after the latest fashions, Hakkas must find something that sells, and they have to developing markets quickly to attract a following and take their place in the mainstream media. Many people seem to agree that the natural place to get a foot in the door is in pop music.

Chang Hsueh-shun, a Hakka legislator from Chutung (Hsinchu County), mentions Lin Chiang, a male singer who broke Taiwanese pop music out of its "vale of tears" rut by recording some popular upbeat music. His style was a breath of fresh air, and sparked a boom for Taiwanese music. Among Taiwan's aborigines, Ami singer Difang (Chinese name: Kuo Ying-nan) had a song incorporated into the theme song for the 1996 summer Olympics in Atlanta. Among the younger set, Chang Huei-mei ("Ah Mei") has established herself as the leading female pop vocalist, and her inclusion of indigenous flavor in her songs has greatly increased the cachet of aboriginal music.

Hakka singers Bobby Chen and Chen Yung-tao, and the rock band Shan Kou Ta have started to record Hakka songs in recent years. If they can combine Hakka folk music with rock and roll, the idea that Hakka culture is "cool" and worthwhile will rapidly catch on.

Once that happens, says Chang Hsueh-shun, Hakka culture can become the "in thing." Hakka youth would no longer feel embarrassed to be heard speaking Hakka, and other ethnic groups would become curious to know more about Hakka culture.

Onward and upward

Says Babuja A Sidaia, an activist seeking to raise the status of the Taiwanese language, "Sometimes I ask my Hakka friends, 'What impact have you Hakkas had on Taiwan's culture?' I just want to get them to think a bit." According to Sidaia, most people spend their entire lives in Taiwan without ever hearing a single Hakka song, watching a single Hakka movie, or seeing a single Hakka play. The lone exception would be Yuan Hsiang Jen ("a person from our hometown"), a novel by the Hakka writer Chung Li-ho, which came to the public's attention when it was made into a movie. Faced with this ignorance, how is Hakka culture to pique the curiosity of non-Hakkas?

Sidaia notes that Hakkas are actually very creative. Lai Ho, who was known during the Japanese colonial period as "the father of Taiwanese literature," was Hakka. Yeh Ching, who was once one of the most popular performers ofoutdoor Taiwanese theater, was also Hakka. Hou Hsiao-hsien, who achieved international fame making movies with a strong "down home" Taiwanese flavor, traces his lineage to Mei County in Guangdong. The king of Taiwan's TV variety show hosts, Hu Kua, is from Miaoli County. Plenty of Hakkas have made a name for themselves in Taiwan, and if they could stress their Hakka ethnicity a bit more, it would help to raise Hakka consciousness and create a sense that there is something valuable about Hakka culture.

The street march to raise Hakka visibility is over, but the effort to overcome the barriers that keep Hakkas from achieving prominence in political, business, and cultural circles has just begun. Still, as Hugh Lin states, "When you make up 20% of the population, you have no right to be pessimistic." Even though the Hakka movement has produced few concrete achievements in the past decade, it has spurred a lot of thought, introspection, publicity, and alliances. As a result, Taiwan is now at the forefront of a worldwide Hakka movement. A great deal of energy has been built up. In what direction will it flow once it has been released? We look forward to finding out.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)