A string of pearls

The climax of a visit to the museum is a visit to the Avatamsaka World, which as of this writing is not yet completed. Here at this very impressive museum, constructed entirely with donations from faithful followers of Buddhism, the Avatamsaka World is the only room with a deeply Buddhist ambience. According to interpretations of the Avatamsaka Sutra, our universe is formed of pearl-like individual objects strung together in a net, so that it is difficult to separate what is real from what is illusion; past, present, and future exist side-by-side; and no individual can exist in isolation. As a result, people should live in the present, embrace goodness and do good deeds, so that the universe will tend toward harmony.

This Buddhist philosophy finds concrete expression in the MWR itself, in particular through the medium of the Internet. The Internet in fact closely resembles the intangible, borderless world of connected individual "pearls." We never know how extensive or long-lasting might be the impact of a single small idea or action, but we can imagine that every molecule in the vast universe is connected.

The area which illustrates such profound ideas is also, interestingly enough, the one that provides the most plain fun. The youthful Internet game crowd will probably find it easiest to navigate Avatamsaka World. With just a few commands, you can link up to religions, customs, philosophies and celebratory rituals and festivals from around the world. Visitors will discover that religion is in fact a way of life, and that no matter what you believe, or don't believe, the life of every individual is nevertheless touched by the shadows of religious culture. For example, no matter how deep or shallow your understanding of Christianity may be, you may get Christmas presents. Of course, the thing to most look forward to is the unknown opposite number you may link up with, so that life is filled with the pleasure of unexpected surprises.

Finally we come to the Great Hall of World Religions. Ten major religions from ancient times to the present-including Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Shinto, Buddhism, Taoism, primitive religions, and the belief system of ancient Egypt-are introduced to the visitor through precious artifacts. Not only does the visitor come to understand and appreciate these crystallizations of human civilization, but naturally to feel a sense of awe and respect as well.

Ideally, this brief journey through the MWR should allow visitors to transcend the noise of ordinary existence and reflect on the meaning of life, and then return to aspects of concrete existence in the Avatamsaka World. It's like a spiritual sauna. Or, like a pilgrimage to the great cities of the ancient world, for modern people this is a relaxing and enriching education. Unfortunately, construction of the Internet part of the Avatamsaka World is still ongoing.

Thus far, the museum is not widely known, and most visitors are either intellectuals with a particular interest in culture, or students led by their teachers. Thus, the "soul-saving" work of founder Hsin Tao is still in its initial stages. Yet we must not forget that this step, though small, is the product of more than a decade of effort on the part of Buddhist clergy and of thousands and thousands of the faithful followers or friends of Dhar-ma Master Hsin Tao.

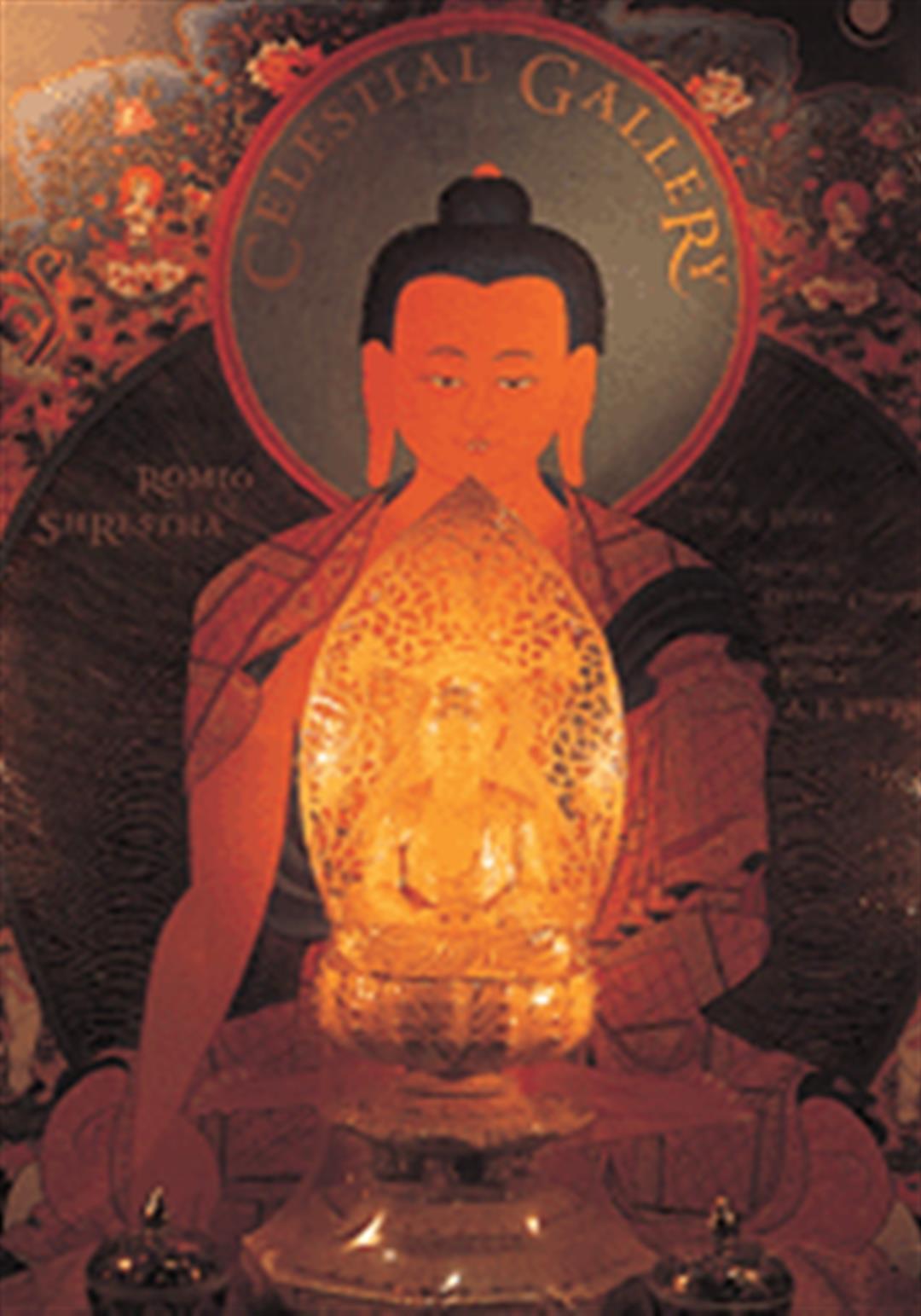

A Buddhist artifact in the museum's exhibit area.