What immediately comes to mind for Chinese people at the mention of Tunhuang is the variety of Buddhist sculptures, ferocious and serene. Within Tunhuang's more than 400 caves there are preserved over 2,000 colorful carvings and 40,000 square meters of wall paintings. The work was completed over a period stretching from the Northern Liang of the Five Dynasties period to the Sung dynasty. It is the largest discovery of Buddhist caves in modern times with the longest history. From the Bodhisattvas which are placed in a pictorial story about conversion in the early Buddhist period to those who entered the world with happiness, grace and serenity, the Bodhisattvas have a different character in each cave. Along with the sculpture of the Yunkang grottoes and the calligraphy and painting of the Southern Dynasties, Tunhuang serves as one of the three legssupporting the tripod of Chinese medieval art.

Tunhuang's Treasure Is Its Manuscripts

But what fascinates people about Tunhuang does not stop there. It was in 1899 that the monk Wang Yuan-lu stumbled on a collection of ancient scrolls and books quite by accident in the caves. Up to that time Sung wood block prints had been considered by scholars to be the be-all-and-end-all of Chinese literature and art history; suddenly there appeared from Tunhuang more than 40,000 manuscripts concerning the activities of people in the Tang dynasty, a huge number of concrete records of every facet of life at that time that could only enrich other areas of research.

For example, Tang dynasty IOUs, contracts and accounts of interest rates provided economic historians with important evidence. All kinds of censuses, land records and documents of civic associations brought to light the pattern of land transfers and civil activities. Yet the mass of Buddhist sutras and ancient literature was even more important for instilling new life into literary, historical and philosophical research. Tunhuang studies had begun.

It was just unfortunate that the manuscripts came to light at the height of the wave of enthusiasm among Western scholars for archaeological research in Central Asia at the end of the nineteenth century. With the chaotic Ching court possessing neither the means nor motivation to preserve the historical relics, close to half were bought--or misappropriated--by foreigners and scattered throughout the West.

Because the Australian-born British archaeologist Sir Aurel Stein and the French sinologist Paul Pelliot took away large amounts of manuscripts early this century, today there are more than 9,000 chuan in the British Museum and some 5,000 chuan in the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris. Others went to Japan, America and Russia.

Over the Sea to a New Discipline

Unfortunate or fortunate? Would the treasures of Tunhuang still be preserved in their caves today if they had not been surreptitiously removed? Or might they have been destroyed? The scattering of manuscripts to several countries has taken Tunhuang studies across the seas so that today Paris, London, Japan and Leningrad have all become centers of study. Japan alone has published more than 3,000 papers--even more than China itself.

Among these scattered resources from Tunhuang, the collection in the Soviet Union only came to light in the 196Os. Between 1909 and 1914, Sergei F. Oldenberg, the former head of the archaeology department of the Russian Institute of Oriental Studies and scholar of Buddhism and folk studies, went twice to Sinkiang and Kansu and took away many treasures. Among these were more than 300 manuscripts and 18,000 fragments discovered at Tunhuang. This collection is now held at the Institute's Leningrad branch. Apart from Buddhist sutras lying outside the canon, it also contains manuscripts of various kinds of fiction, such as the Sou Shen Chi and Hsiao-tsu Chuan, poems and songs and Taoist and Confucian scripture.

In 1957, so as to further research of Chinese literature, Menshikov began researching the Institute's manuscripts. Under his leadership a small research group first ordered and catalogued the collection and completed two volumes of the Index of the Leningrad Tunhuang Manuscripts. At the beginning of the 1960s, one of the founders of the group, Chuguevsky, set about translating the notes, letters and IOUs of the collection into Russian, adding explanatory notes and issuing research papers.

The Rustic Scholar

In 1963, Menshikov himself produced a thesis related to three chuan among the Tunhuang pienwen literature, including the Wei Mo Chieh Sutra, Sui Ching Chi and Shih Chi Hsiang. Pien-wen is a literary genre of stories told on religious festivals at Buddhist or Taoist temples in the Tangdynasty. The narrator would tend to structure his tales around themes from the Buddhist sutras or literature and embellish them, resulting in something between poetry and narrative prose and unwittingly creating a new form of Chinese literature in the process. Menshikov went on from here to continue his research into the collection and thus became an important figure in the field of Tunhuang studies.

"He is a world-class Tunhuang scholar," says Professor Chin Jung-hua of Wenhua University's Chinese department. Menshikov's achievements are recognized the world over. Moreover, when he attended the international conference on Tunhuang held in Taipei last April he became the first Soviet scholar to accept an invitation in forty years.

Among the books filling the research room of the Institute crammed on the bank of Leningrad's Neva River, the hoary Menshikov scours the sutras, his silver hair revealing a certain erudite glamor; vigorously striding towards his out-of-town residence and bending over to tidy his vegetable patch, there is also something about him of the sincere air of the peasant. The Soviet Union might have shortages of materials, but in hisLeningrad residence the books are wall to wall from sitting-room to bedroom. He dons an apron and prepares a simple but plentiful meal for his guests.

Between these places we interviewed Menshikov about the course of his research. Talking with confidence and composure he told of how four years ago he had his first opportunity to step on Chinese soil like "a toothless old squirrel on a cart of nuts with no way to digest them." Below is the result of our discussions:

The Fascination of Documentary Research

Q. Can you talk a bit about how you came to Chinese studies and how you became particularly interested in Tunhuang?

A. My path to Chinese studies was not at all complicated. When I was young I wanted to be a geologist. In middle school I joined a geological expedition to Irkutsk and while I was there I read a lot of works by exiled writers which gave me my love of literature. In my father's generation there was a scholar of Mongolian on the oriental faculty of LeningradUniversity who suggested that I do research on oriental literature. He told me to start with Chinese culture because, if I wanted to understandMongolia, Central Asia, Japan, Korea, Vietnam and a number of other cultures, I would first have to know about the Chinese culture which had such a powerful influence on all of them. Later I became a student at theChinese research section of the Oriental Department of Leningrad University.

I like plays very much and my earliest topic of research was the reform of modern Chinese drama. After graduation I began working at the Leningrad branch of Institute of Oriental Studies and wrote my first doctoralthesis on the Sou Shen Chi. It was at this time that I saw Chen Chen-tuo's History of Chinese Literature, History of Vernacular Chinese Literature, and understood that if I wanted my research into the development ofChinese literature to progress further then there were very important resources among the Tunhuang manuscripts. It just so happened that I alsoknew there were some Tunhuang manuscripts at the Institute in Leningrad. For me this first hand research was much more fascinating than third hand theorizing, so I decided to make Tunhuang pien-wen the subject of myfinal doctoral thesis.

Finding Chinese Literature's Path of Development

Q. Is pien-wen an important element in the development of Chinese literature? Are the resources you have used for your research only available here?

A. There are seven sections of pien-wen in our Tunhuang collection. Apart from mainland China, it is probably the largest at present.

In the past we only knew that Sung-dynasty literature and what came before it were two different matters. It was only after the Tunhuang pien-wen came to light that we became clear about how the p'ing-hua style developed out of the antithetical p'ien-t'i style and poetical form. You could say that pien-wen is the precursor of the new Chinese literature, drawing on the forms of Tang poetry, Buddhist sutras, fiction of the Six Dynasties and feeding into Ming and Ch'ing novels, drama and story telling.

Q. So the aim of your research is to clarify the path of the development of Chinese literature?

A. Yes. Pien-wen can make a very positive contribution to the understanding of the development of Chinese literature. For example, my pienwen research into the meter of poetry and lyrics revealed that there was already a great change in the pien-wen poetry and lyrics of the Tang dynasty, which could be said to already be preparing the ground for the transformation of meter in the Sung ts'u. Does not this already enlighten us about the development of poetry and lyrics in Chinese literature?

Q. If pien-wen played such an important role in the development of Chinese literature, why is it only to be found at Tunhuang?

Finding Pien-wen in Tunhuang

A. From the history of Buddhism you can discover that in AD 845 Emperor Wu-tsung of the Tang dynasty destroyed Buddhism, closed many of the temples and forced the monks to flee and that many Buddhist works were lost. Then we find that if we look at pien-wen today there is an antigovernment element in some of it, such as criticisms of corrupt bureaucrats, which is quite natural if you have been vanquished. Another aspect is that the Tang dynasty gave a degree of independence and freedom to remote peoples, so pien-wen could be preserved in these far away places.

I have a concrete example from my own research. In the middle-ages there was a monk called Wen Shu in Ch'ang-an. Before Wen-tsung's dissolution of Buddhism, Wen Shu's position was very high and he would often takepart in the debates between the three religions in which the emperor would summon representatives of Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhism to expound on matters of state.

But after AD 845 it seems that Wen Shu is not mentioned; only in the article by Tuan Cheng-shih is it mentioned that Wen Shu has been exiled. Seven years later a delegation came from Tunhuang to Ch'ang-an to request rehabilitation. They were made a prefecture and a number of manuscripts were given to them from the Ch'ang-an temples. It was thus that the Ch'an-gan pien-wen may well have gone west. The Wei-mo Chi and Hua-fa Sutra, according to my research, may then have been written by Wen Shu.

Scrutinizing Chuan and Weighing Words

Q. What is the hardest thing about researching primary sources?

A. I was very audacious when I was young and produced my first pien-wen research paper in three years. Later I came to understand that if I wanted a deeper understanding of pien-wen, apart from the content, structure and style of writing, I still needed to research the peculiarities and cultural context of its grammer, vocabulary, ideograms and so on. An example is the Shuang-en Chi, which originally was translated from a sanskrit story about the affection of two rulers for their parents. Apart from researching the adaptations of this story, the connections between the story's ideal of filial piety and the Chinese ideal, I also put together a dictionary of the vocabulary and a chart comparing erroneous characters. This kind of work takes a lot of effort. Every piece of my later pien-wen research has taken more than five years.

Q. The Tunhuang manuscripts are extremely valuable historical materials and people have felt that those in possession of them have been very con servative about preserving them and allowing access. What is your attitude?

A. The 25th international conference on oriental studies held in Moscow in 1960 was the first time that sinologists in other countries knew we were in possession of Tunhuang manuscripts and research. After the meeting they came to Leningrad and asked to see them. At that time the academician in charge of our research institute said: "Let them see! We do not need to hide our resources!" Since I published the catalogue of the Leningrad collection there have also been numerous requests from foreignscholars to see the manuscripts and I have not stopped them.

Searching But Not Researching?

Q. So your attitude is quite open. What kind of interest then is there among Soviet sinologists towards these materials?

A. Many sinologists from different countries are interested in our Tunhuang materials. In 1964 the French Academie des Sciences supplied us with research funds. However, there is a lack of interest among Soviet sinologists. Although the Institute is the main center for Chinese researchin the Soviet Union, everyone still wants to do theoretical research. There is a lack of people interested in the concrete works of literature.Out of the five members of the original research group, only Chuguesky and myself are left--both over sixty years old and the "youngest" Tunhuang scholars in the Soviet Union!

Apart from this, due to our lack of paper and insufficient budget we are very slow to publish. For example, my work on the Fa-hua Sutra was lying at the printer for eight years. Overall, there are still many problems hidden in our research.

Q. What kind of problems? Are they very serious?

A. For example, I researched the Shuang-en Chi and its relationship tothe Chinese idea of filial piety. Later a Chinese-American did the sameresearch with views very close to my own, but it was his research that came first to people's attention.

There are a lot of people who come to see the Tunhuang materials but are only interested in seeing the manuscripts and do not pay any attention to our own research. I have always researched the particularities of diction in pien-wen and recently mainland China's Tunhuang Quarterly also published material on this area but without mentioning my research atall.

Now that everyone knows we are researching Tunhuang manuscripts here, they can contact us by letter and exchange interests. I think that researchers cannot afford to ignore related research done by their predecessors. If it is because they do not understand Russian, then they can use the Japanese method--collect all the papers and translate the lot.

Getting the Whole Picture from Chinese and Foreign Research

Some Chinese scholars might also feel, "This is our own culture. How can foreign research be letter than our own?" Or, "If our materials were returned to China then we could research them better than foreigners." However, if we look at the sinological research in France, Japan and other countries, we often come across topics that are not researched in China. Is it really possible that foreigners cannot research the Fa-hua Sutra? Perhaps our position and point of view are not the same, but whose conclusions are correct? Only time will tell! Conclusions about things viewed from different points will certainly be different, but if the two ways of looking are put together than perhaps we get closer to the truth.I do not want to criticize anybody in particular but a dismissive or discriminatory attitude in academic research is not of any help.

Q. Do you see this as a reaction to the past misappropriation of Chinese artifacts by the West?

A. We cannot judge the past by the standards of the present; many of the works of Russian artists are today in Paris, Sweden or Germany. Eventhough you can buy antique treasures today, you are not allowed to takethem out of the country. In the past there was no such law. The nineteenthcentury archaeologists also only went to do their work in Central Asia with the permission of the Ching court.

Past is past and the present has its own way of doing things. Just look at developments in facilitating study. Today we are collaborating with a publisher in Shanghai to produce reproductions of our Tunhuang manuscripts so that anybody who is interested can get hold of them.

Translating The Romance of the Western Chamber

Q. Apart from your Tunhuang research, we know that you have translatedquite a number of works of Chinese literature. Can you tell us a bit about this translation work?

A. When I was at university I began translating The Romance of the Western Chamber. At that time there were a lot of Chinese students in Leningrad and I gained a deeper understanding of the work from them. When thetranslation was published in 1960, I became the first person to translate it into Russian, although I did not realize it at the time.

Q. Is it usual for Soviet university students to translate foreign works into Russian?

A. It cannot be considered as usual, but I was fired by interest and the publication was unexpected. At that time there was a close relationship between China and the Soviet Union so the publisher was very interested in this book. After finishing The Romance of the Western Chamber I went on to translate The Peony Pavilion but unfortunately, only got a quarter of the way through. Later on another sinologist saw my translation of The Romance of the Western Chamber and asked me to translate the poetry in The Dream of the Red Chamber.

In 1955 I also translated The Water Margin and the two Yuan dramas, Ch'ien-nu Li Hun and Chang Sheng Chu Hai. As for my first doctoral thesis on the Sou Shen Chi, I have already translated sixteen chuan and I hope to release the complete translation this year along with my own index.

Q. Can you really have so much time outside your research to do all that translation?

A. Endless work, alas! Actually, I really like to translate works of literature. Recently I also translated a novel about Empress Wu, but the publishers thought it too long and cut out a third. In the past works published on Chinese literature in Russian had always been very welcome inthe Soviet Union because they are not like treatises. [Laughs.] But since perestroika the publishers have been responsible for their own profitsand it has become harder to find one.

Old Toothless Squirrel?

Q. Have you been to Tunhuang and if so then what was your impression?

A. I first went to China in 1989 and that was to Tunhuang, where I stayed for ten days. Of course I was very moved by the relics, but this hasalready given way to sadness--so many of the wall paintings in the caves have become patchy, like fish scales, flaking off bit by bit. The Northern Wei clay figures are eroded by the wind so that you cannot see their complete faces.

The mainland has asked experts from Japan and France to help with the preservation but they still have not found a solution. Even more important is the lack of money. Many overseas Chinese and tourists have given money for restoration of the caves but it is just not enough--just likewith our publishers. I really do not know whether this is a problem forthe whole world or just a problem of socialism.

Q. So you only set foot on Chinese soil for the first time three yearsago?

A. Don't be surprised! For someone who has researched Chinese culture never to have been to the country he is researching for thirty years--even I think that's incredible. But in 1989 the five people from our research institute travelled there together and it was the first time in China for three of us! So I really did not speak Chinese well. When I wasat Tunhuang I saw a young lady drinking fruit juice and asked her in Chinese, "Is it nice to eat?" She solemnly corrected at me and said, "To drink!" How embarrassing!

When I was a student I had an opportunity to be sent to China but thenthe Korean War broke out. It looked like the Soviet Union might get involved and the trip was cancelled. Later on there were a few opportunities, but because I was not a member of the Party, they came to nothing in the end. After the Cultural Revolution, apart from diplomats, nobody could go to China. We now have more freedom to leave the country but we lackhard currency.

In Russia we have a story about a squirrel who worked for a lion. Every day the lion promised to give the squirrel his pay but it never materialized. Then, when the squirrel retired, the lion finally gave him a cart of nuts. But the squirrel had already lost his teeth! I am that squirrel! [Laughs.]

Lonely Little Index Cards

Q. After all these years of sinological research, what are you most proud of? What beliefs have supported this research into a completely different culture?

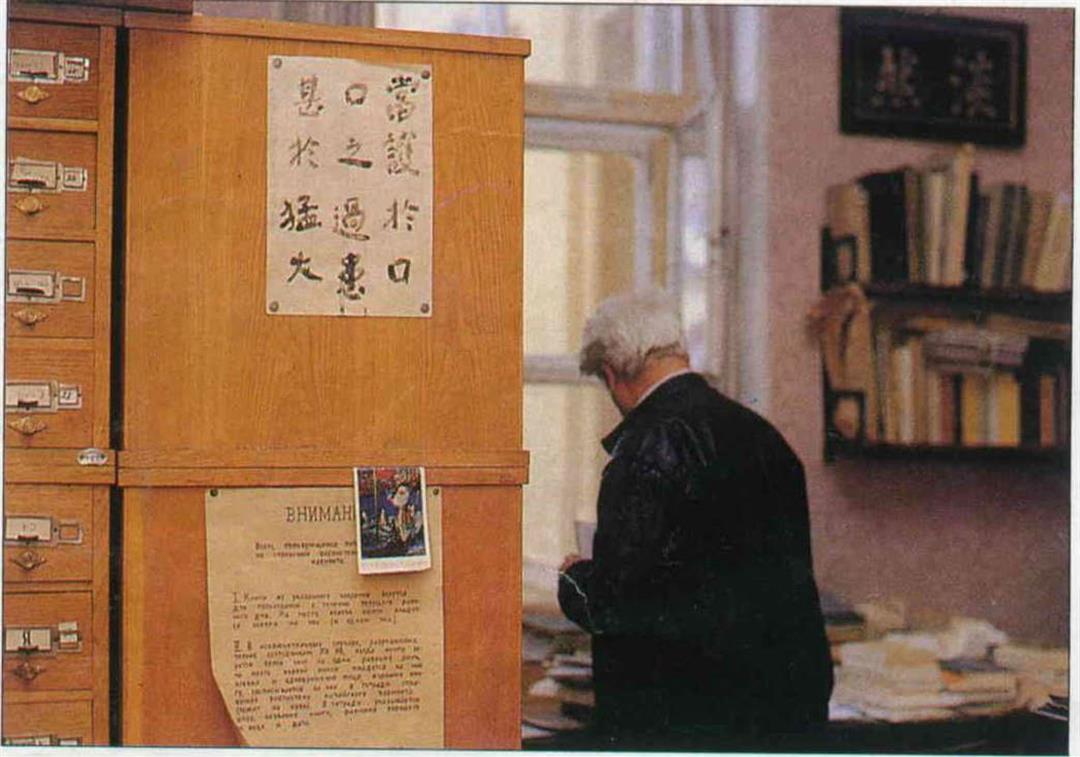

A. My research has revealed a number of newly discovered works of literature, and is it not new discoveries that make people excited? In factthis kind of work is very lonely. Look, all these card boxes have more than a thousand cards. On each one is written a character or phrase, whenit appears, what is its meaning and what characters it is used in conjunction with, how often it has appeared and how many uses it has! They are here in silence, each one a lonely thing.

I am sixty-five this year and most of my life I have spent solely on Chinese studies. But the further down this road I get, the more significant it becomes.

In the past, Europeans liked to compare the development of Europe and China. Independent developments can of course be researched comparatively. But there are people who take Europe as the standard by which to criticize other civilizations, with which I do not agree. I believe that every culture is unique. As a sinologist my work is to understand the peculiarities of Chinese civilization and clarify why it developed in the way it did. The implications of such a problem are too many, too wide and too interesting. Going forward step-by-step for nearly half a century,I still have not had time to think about what beliefs are needed to keepat it.

[Picture Caption]

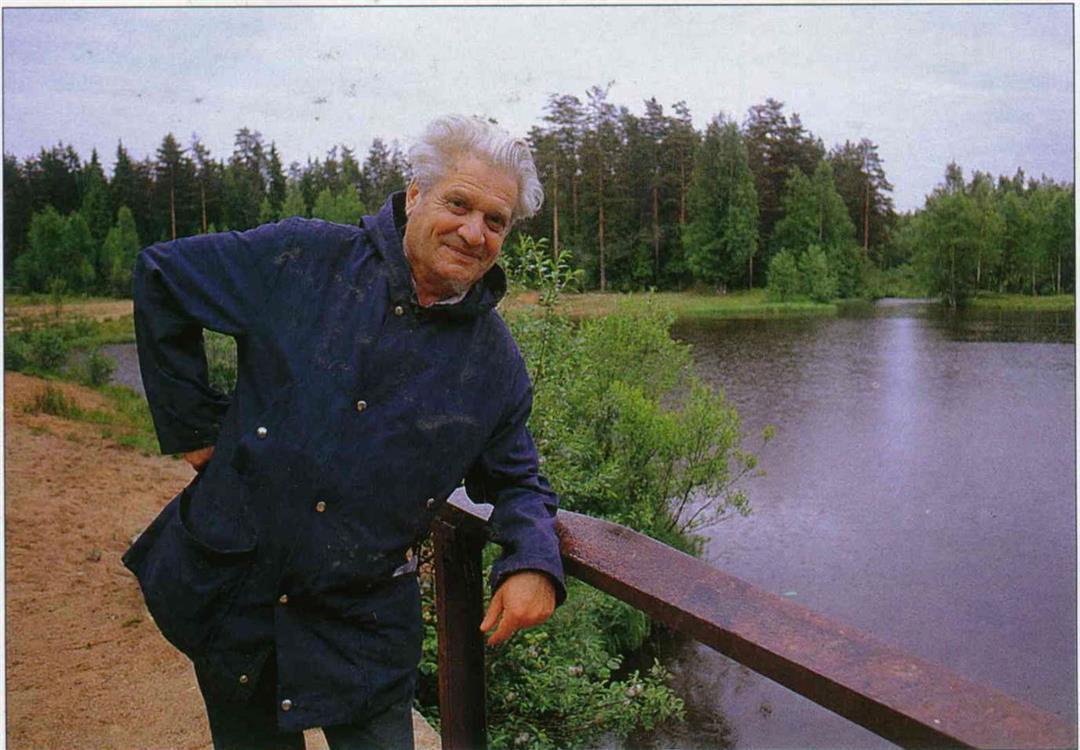

Soviet sinologist Menshikov under a photograph of his predecessor. Menshikov's favorite pastime is walking by the lake near his country res idence.

Menshikov's favorite pastime is walking by the lake near his country residence.

Wall-to-wall books and mottoes reveal the nature of the sinologist.

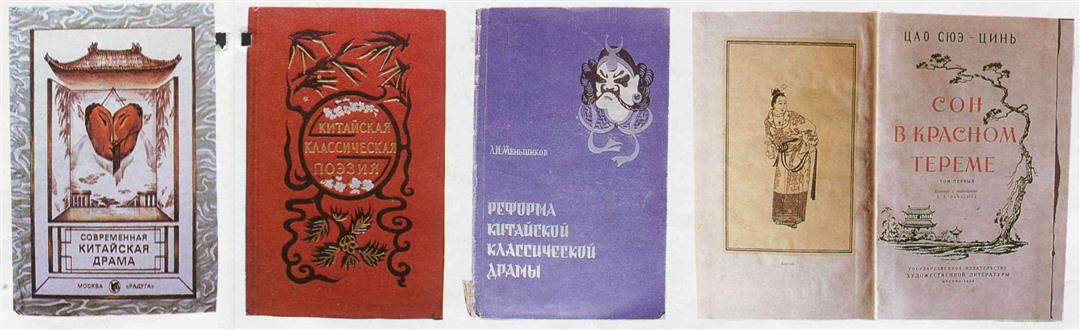

Menshikov and some of his many works, including Tang poetry, The Reform of Chinese Drama and an essay on The Dream of the Red Chamber.

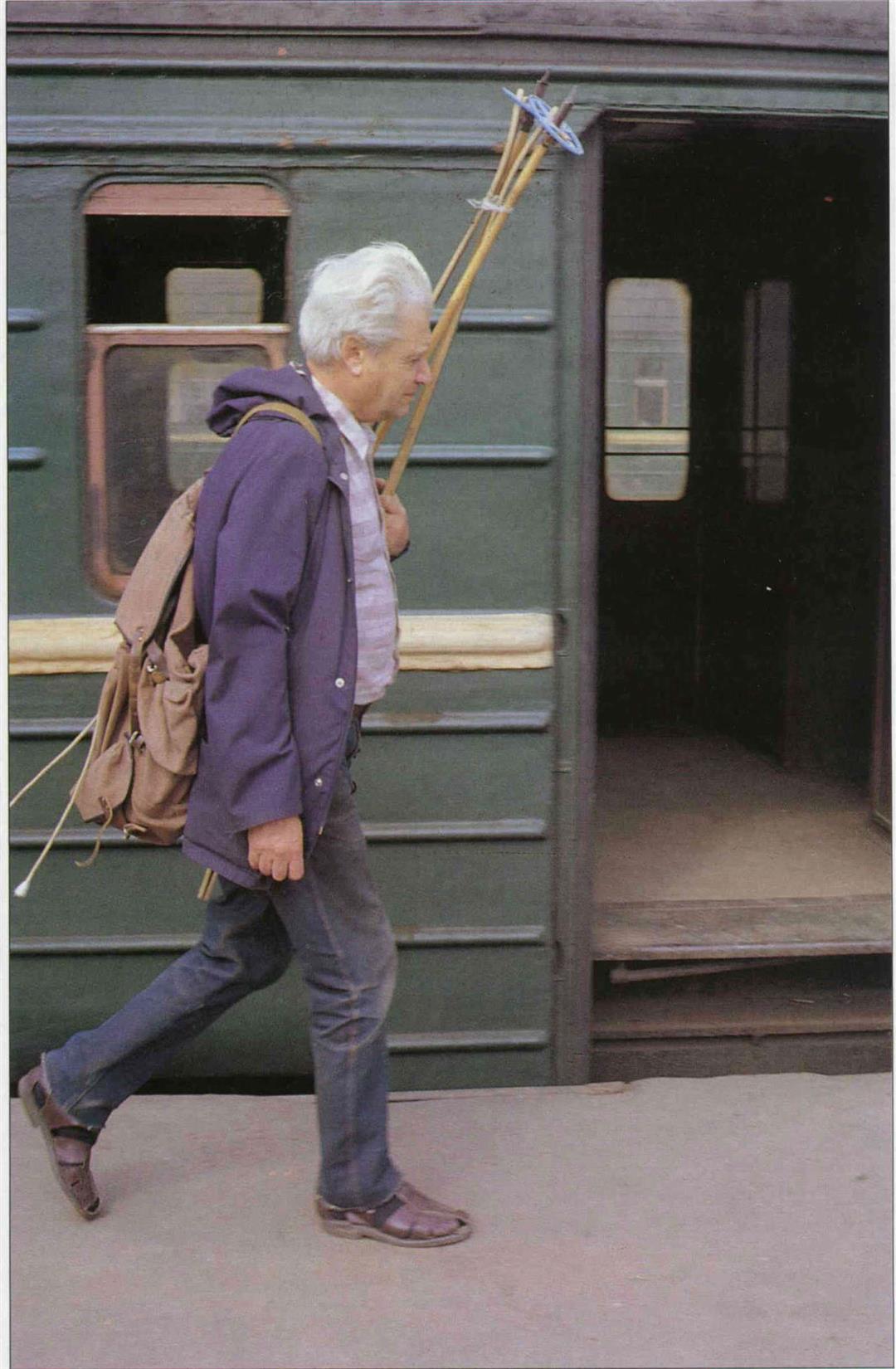

Full of vitality, the silver-haired sinologist puts on his back-pack, jeans and sandals and goes to his country cottage for the weekend.

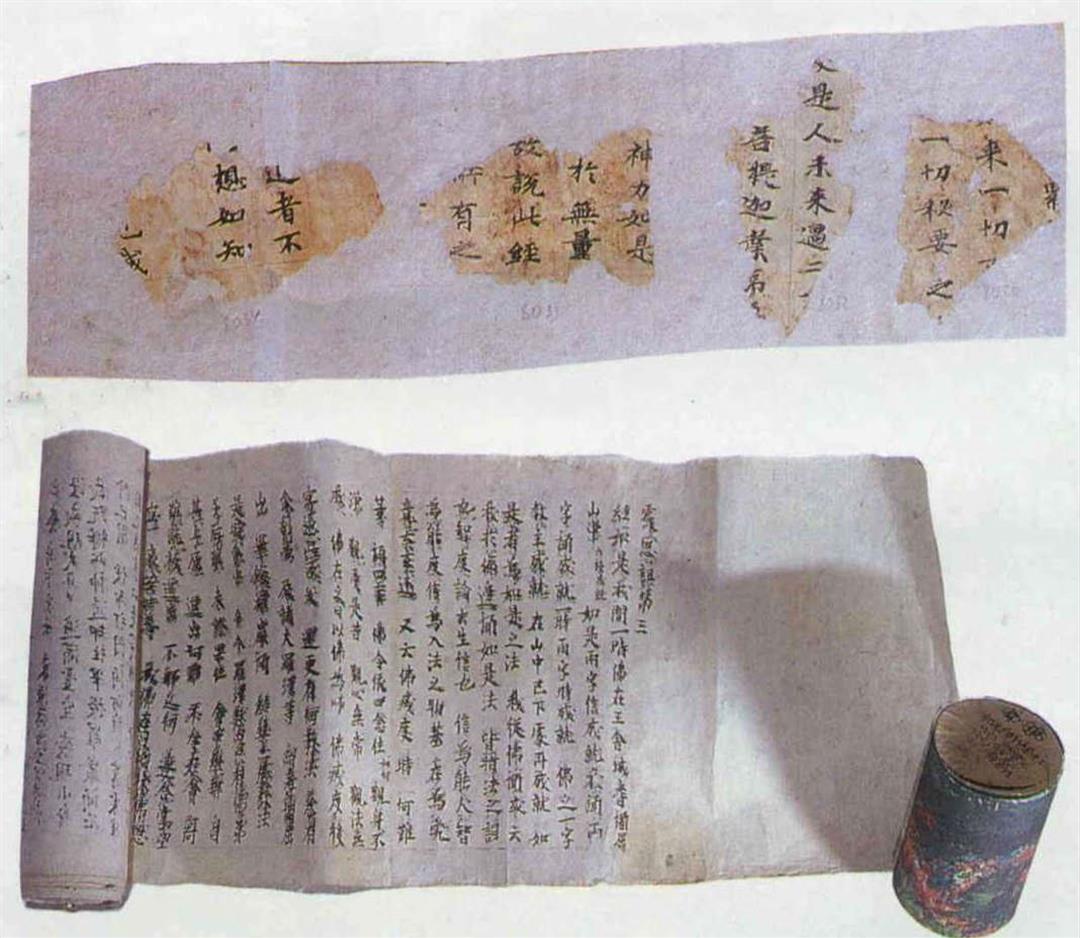

There are more than 300 manuscripts in Leningrad including many fragments (above) and the manuscript of Shuang En chi (below).

Menshikov's favorite pastime is walking by the lake near his country residence.

Wall-to-wall books and mottoes reveal the nature of the sinologist.

Menshikov and some of his many works, including Tang poetry, The Reform of Chinese Drama and an essay on The Dream of the Red Chamber.

Full of vitality, the silver-haired sinologist puts on his back-pack, jeans and sandals and goes to his country cottage for the weekend.

There are more than 300 manuscripts in Leningrad including many fragments (above) and the manuscript of Shuang En chi (below).