Gathering together with friends to compose poetry has been a pastime enjoyed over the whole course of Chinese literary history. In Taiwan, poetry societies wrote the first page in the history of the island's literature, and they have operated without interruption for hundreds of years. It's just, now that most of their members are elderly, who will carry on the legacy of these once flourishing groups?

On the second floor of a bathroom fixtures supply company, the "Keelung Poetry Research Society" holds its monthly meeting. Its chairman Wang Chien writes the topic for poems on the blackboard: "gathering around the stove." With New Year's approaching, it's a topic much in keeping with the spirit of the season. By custom, a woman member draws a lot to select the rhyming scheme, and the contest begins. They've got only two hours to finish their poems. Wearing reading glasses, the elders start to fill their pages, which are specially designed for composing poems. On the side of the table by the window sit the greenhorns--"youngsters" in their forties. Some with shallow poetic experience seek inspiration in reference books like the Shiyun Quanbi.

"They are composing 'hitting the bowl' poems," explains Chen Shu-kang, who is standing off to the side. The name comes from the method formerly used to time poetry competitions. In the old days they'd tie a coin to a cotton thread above a bronze bowl and attach an inch-long stick of incense to the middle of the thread, which they would light after the topic was given. When the stick was finished and the thread burned, the coin would fall to the bowl with a "dong" and the contest was over. Although they've been using watches for years now, they still make an allusion to the coin "hitting the bowl."

When everyone has turned in their poems, the rules require that two copies be made of each, which are then given to judges sitting in separate rooms. "This prevents cheating and social pressures, and it's fairer having two judges," explains Wang Chien. "But nowadays we just send them to be evaluated by a poetry association in another city or county."

The results of the last competition are in. Just as this month's poems are half finished, the directors start to call out names one by one, giving out awards for last month's efforts. Almost all of the poems that aren't in the top three still get honorable mentions. The consolation prizes, covered smartly in wrapping paper, are either socks or toothpaste, and the grand prize is MSG! Laughing, people say that they can use it to enhance the flavor of their holiday cooking.

Reading poetry and making friends

The scene just described is typical of poetry societies. One can't divide composing poetry from reciting it, and while waiting for the winners to be announced, people read poems to raise everyone's spirits before they eat and go on their separate ways. Besides poems composed extemporaneously at meetings, it is popular these days to take assigned topics home, much like homework at school, and then bring the completed works to the next meeting to be read and critiqued.

Similar poetry societies exist in cities and counties all across Taiwan. Some have long histories. Taipei's "Ocean Society" was established over 80 years ago, and its former members include famous Japanese-era poets such as Lien Ya-tang. Even the newer groups have been established for a decade or two. Sometimes the break-up of an old poetry society would give rise to a few new ones. Sometimes younger poets who couldn't see eye to eye with the elders in charge of a society founded a new one. The groups show varying degrees of vitality. Some directors are already in their eighties, and society activities have virtually ceased. The Keelung Poetry Society counts as a relatively lively one for holding a meeting just once a month.

Apart from members' meetings, these groups also take turns holding inter-society activities, such as poetry readings. The grandest in scale is the "Great National Poetry Reading" held every Poets' Day. Several hundred people always attend. Some enthusiasts are members of several poetry societies, and go far from home to attend meetings. Contrary to the stereotype of the poet-scholar, members come from all walks of life: factory owners, bureaucrats, teachers, legislative assistants.... Very few were Chinese literature majors in college. For them, poetry is an avocation. Many threw themselves into their careers when they were young, casting aside poetry and literature as they struggled to make a living. They waited for things to settle down before picking up their old interest years later.

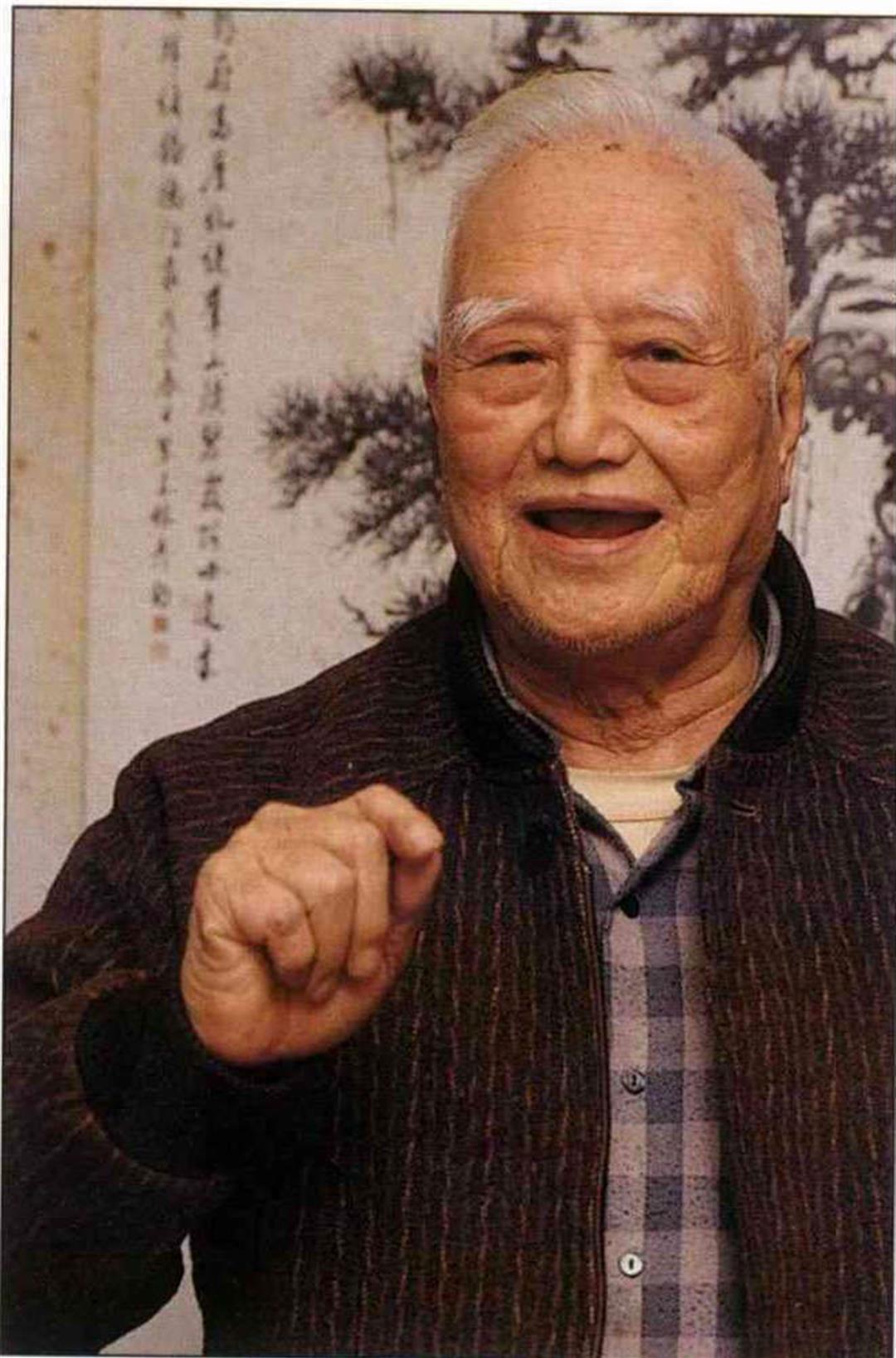

"The pleasure one gets from poetry is like what a general gets from deploying troops or what a high-level manager gets from directing the operations of a whole company," animatedly describes Su Nai-chang, a member of the Chiayi Poetry Society. He finds it fascinating to see how a few dozen words can be used to express an entire story.

Classical and down-home

When you ask them about how they first became interested in poetry, most of these elder poetry enthusiasts recall studying Chinese in private village schools during the Japanese era.

Wang Chien, who is now in his sixties, read Japanese books in school. "When the Chinese retook Taiwan after World War II, the schools began teaching Mandarin phonetic symbols. By that time I had already graduated, and couldn't study formally any more, but to add to my learning I studied Chinese privately. After reading the Four Books and other classics with my teacher, we turned to classical poetry, and I found it fascinating. That's when I started."

Others come from scholarly families. Their fathers or grandfathers were scholars, perhaps even successful candidates in the old civil service exams, and they were introduced to poetry at a young age. Chiang Meng-liang, director of the Keelung Poetry Society, remembers that his father was a member of a Japanese-era poetry society, and recalls meetings of his father and his poet friends. "I still remember my Four Books, which I studied privately. It's like I've stored their phrases in my belly, and they come out on their own accord when I compose poetry."

Poetry societies have a long history in mainland China (see the accompanying article), and they came over to Taiwan with Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong) in the Ming Dynasty. When the ROC government moved to Taiwan in the late 1940s, high officials from other provinces came to the island, and they formed poetry societies with a heavy political flavor. The China Poetry Research Association, for instance, is always chaired by the President of the Control Yuan, and its board comprises members of the legislature, Control Yuan, Examination Yuan and National Assembly. The ranks of the ROC Classical Chinese Poetry Society are also filled with senior KMT officials, and its magazine, The Voice of Chinese Poetry, often features pictures of gathered government bigwigs.

Still, few poetry societies have been formed by mainlanders, and the memberships of the local poetry societies are still almost wholly Taiwanese.

"Taiwanese poetry societies have two special features," concludes Chien Chin-sung, associate professor of Chinese at National Sun Yat-sen University, who is a forceful promoter of poetry activities and himself a poet. First, they are very much connected to traditional culture, because their style of poetry is closely related to the classics read in the Ming and Qing dynasties. Second, because the members of these societies don't have a high level of education, the clubs are very much a part of local Taiwanese culture--virtual reflections of common Taiwanese society. "These poetry societies were not established in the modern academic era, and so they are representative of local temple fair society," Chien says.

In praise of Taiwan's eastern peaks

Why is it that what was originally a gathering of literary sophisticates is now viewed as part of the realm of folk culture? Why does Taiwan have so many poetry societies? And how did they develop?

As Huang Yung-wu, a professor of Chinese, tells it, poetry can make up for deficiencies in history, because "poetry can enter deeply into the very fabric of one's life, to one's inner spirit. Sometimes it's more real than history." From the incomplete records of poetry societies, one can piece together how Taiwan inherited a cultural legacy from mainland China before striking out on its own.

"Taiwanese poetry societies can be traced back to the Fu and Ji societies in the late Ming dynasty," writes Chinese Culture University Associate Professor of Chinese Liao Yi-chin in The History of Poetry in Taiwan. Poets of the Fu Poetry Society were among the settlers Koxinga led from Fujian, and they brought poetry with them.

In 1685, during the rule of the Qing emperor Kang Xi, a pro-Ming settler from Koxinga's era named Shen Kuang-wen established a poetry society in Chiayi with other poets. At their first meeting, the topic for poems was "Dongshan"--or "the eastern mountains." Because the mountains of eastern Taiwan bore few human footprints, and no one had written verse in praise of them, they named the society Dongyin, meaning "intoning the eastern mountains." This was the beginning of poetry societies in Taiwan, and also the first page in the history of Taiwanese literature.

For those full of grief and anger at being so far from home, it is only natural to express their feelings in poetry. They approached this new island with fresh eyes, and the customs of the island's people and its scenery would both enter their verse. Take, for instance, such vivid descriptions of pastoral scenes as "The petals of the peanut flowers fall to the ground, and the sweet potatoes are ripe." How about this description of aboriginal society: "The aborigines celebrate a wedding with song under the moon, and all the villagers, whether married themselves or not, gather." Or this description of the locals' lack of sophistication: "Ink has never touched their hands or hearts, but their mouths are stained through and through by betel nuts."

Thriving under Japanese rule

The golden period for poetry societies in Taiwan would come during the Japanese era.

"Many educated Taiwanese back then grieved over the island being severed from China," Liao Yi-chin says. "With the civil service examination system discarded, the literati realized that what they had studied would no longer be of any practical use, and so they consigned their literary talents to verse." The formerly renowned Chestnut Leaved Oak Poetry Society of Taichung takes its name from the tree described in Zhuangzi that survived because of its uselessness. When such leaders in the fight for Taiwanese participation in government as Lin Hsi-tang and Tsai Hui-ju joined the society, it became a base for pro-Chinese activities. Once, copies of its poetry journal were prohibited and destroyed for promoting an ethnic Chinese consciousness.

In 1911 Liang Qichao came to Taiwan at the invitation of Lin Hsien-tang, and the poets of the Chestnut Leaved Oak Society read poetry together in celebration. The famous poet Lin Yu-chun captured the true spirit of the celebrations: "After reading his words for a decade, to see his face at last. Venerating him like an ancient, I doubted I would see him in this life. But now I have enjoyed the satisfaction of a lifetime, and feel the caress of the spring wind." Besides rejoicing, they also sobbed over their fate of being "severed from the nation of our roots."

The Southern Poetry Society, established by Lien Ya-tang (author of The General History of Taiwan) and his friends in Tainan, and the Ocean Poetry Society, founded shortly afterwards in Taipei, were the day's leading literary societies, and membership in them was highly valued.

Why did the Japanese, after prohibiting Taiwanese from establishing social organizations, not try to suppress these poetry societies? "It was because most of the Japanese officials posted in Taiwan also wrote classical Chinese poetry, and so they cut poetry societies some slack," explains the old poet Chuan Yu-yueh. "In those days the elders in Taiwan would use writing poetry as a way to study Chinese." This was all the more so after war broke out between China and Japan and all private Chinese schools were outlawed. Many joined poetry societies so as not to forget their Chinese. Most of the private schools' former teachers joined too, as the societies assumed many of the schools' old functions.

Taiwan's "new literature" movement took off in the early 1920s, and in this period many of its masters would also write some excellent classical-style poems. Take, for instance, Lai Ho, the father of Taiwan's new literature, who started his career writing classical poems. In old age, when he was very ill, he wrote "The Setting Sun" about Japanese imperialism in its final moments: "The sun's slanting rays yellow as west it creeps/ For what place has brilliance left so soon?/ How short men's torment in the bitter heat/ Behind them rises the waxing eastern moon."

Trans-ethnic poems of praise

With the native Chinese and colonial Japanese both using poetry societies for their own purposes, these organizations had a lot of room for growth. In Taiwan Poetry Societies Lien Ya-tang says that there were a total of 66 such organizations in Taiwan in 1924. The figure had ballooned to 178 by 1936, according to the Taiwan history Taiwan Tungchi. Based on his own research, Liao Yi-chin reckons that the number was probably closer to 260.

Determining historical truth is always a complicated business, and from any single viewpoint it's hard to come to firm conclusions. Did the Japanese really let these societies flourish because they loved classical Chinese poetry? "They wanted to win over the Taiwanese," says Li Ying-hui, president of the Tiaoshan Poetry Society. In fact, poetry writing competitions with two guest judges were first promoted by the Japanese.

In those days Japanese governors-general would often write poems in response to those written by members of the Taiwan poetry societies, and they even established poetry societies themselves. They used their participation as a way to pacify and win over the native literati. Nor were the Taiwanese poets one and all imbued with Chinese patriotism. When Lien Ya-tang was serving as a reporter, for a poetry contest sponsored by the government he praised the Japanese governor-general: "In his embrace our people are protected from calamity." Other poets were scorned for making the most of the word games in poetry competitions to suck up to the powerful.

Those were confusing times for Taiwanese politically. But what can't be denied is that poetry societies were important cultural groups in the Japanese era, tying together some of the most important literary and educational figures. "The poetry societies of today pale by comparison," says Chuang Yu-yueh, an 80-something member of the Ocean Poetry Society. Chuang believes that the poets of former days were more learned. Following generations could only study Japanese, and then after retrocession the method of education changed, leaving the level of Chinese attained by youth far short of its former glory. Was this a necessary result of progress?

Hoarse voices of old poets?

Because the ROC government imposed strict regulations on citizens forming social organizations after retrocession, poetry societies were quiet for a period before once again reviving in the 1970s. Because sensitivity about the character "she"--which means society and was regarded as having socialist connotations (as in the term "renmin gongshe" or "people's commune")--many of these groups changed their names from the elegant "shi she" (poetry society) or "yin she" (reciting society) to "yanjiu hui" (research association) or "lian yin hui" (group reciting association).

In the wake of rapid social change, the voice of traditional Chinese poets has grown ever softer. Poetry was always an activity partaken in by a few, but now that these few are almost entirely elderly, who will carry on their legacy? "The youth of today don't write poetry," say many of the old poets in disappointment. Very few of even their own children have any contact with verse. "There's no money in poetry, and making a living comes first," says Tsai Chiu-chin, executive director of the Taipei Poets Reciting Association, giving voice to what many others know in their hearts. Poetry is a hobby to pursue at one's leisure. But in today's busy, work-oriented society, no one has time for such pursuits.

Arguing that every form of literature has its limits, Ko Ching-ming, a professor of Chinese at NTU, sees a literary age coming to a close. In modern society, vernacular written Chinese has already changed the way people think, Ko believes. The glory of classical literature is a thing of the past that some cling to with affection. But under the pressures of this age, modern poetry changes quickly, getting fresh injections of blood that give it new vitality. "It's like making ceramics. The China Pottery Arts Company can make gorgeous reproductions of classical blue and white porcelain, but this is different from creating modern ceramics," Ko says by way of comparison.

On behalf of the poetry societies, Professor Li Jui-teng of National Central University argues that they have long been unfairly overlooked by the government and academia. "Though the past decade has witnessed great cultural interest in 'the native soil,' the cultural establishment has shown a bias for preserving and developing folk arts. Classical poetry hasn't gotten the attention it deserves."

In poetry circles you often can hear complaints such as: "Performers of hand puppet theater and Taiwanese opera are regarded as national treasures, and the president shakes their hands. But those of us who have spent our time studying the classics of literature aren't given any recognition. It's strange."

Is this just the age-old whining of literati? Can the old poets in these societies still continue to read their poems? Will the glory of the past be relived?

Seeking former recognition

Chien Chin-sung looks at poetry societies from the standpoint of their preserving folk arts and providing education outside of the schools. He recognizes that they face many problems, but argues that if they can recover or rebuild their relationship with the local people, they can serve as an important link between traditional and modern Taiwanese culture.

"Poetry societies were important cultural organizations in the past, and the need in Taiwan for poetry has not declined. Moreover, this tradition is a part of both Taiwanese 'native soil' culture and the culture of the East Asian mainland." Half a year ago, a three-year project into "the ability of Taiwanese poetry societies to modernize" was sponsored by the National Science Council. Chien is now out in the field, making surveys and conducting interviews at each of the poetry societies that will serve as oral history. Then he will investigate the possibility of guiding these societies to become modern organizations, links in the chain of the culture of a community that "help the Taiwanese discover the glory of their ancestors and find cultural recognition that suits their needs."

And what of the current situation in poetry circles? "Everyone feels that their own poems are best, and that others' aren't worth a second glance," Chien observes. Hsu Chih-cheng, an elderly poet and member of Lukang's Wenkai Poetry Society, recalls in his series of memoirs about literary circles, "Others' beloved concubines and one's own poems, however common, are always regarded as exceptional. Cancer may await a cure, but these delusions of the literary are far harder to treat."

Poetic patchwork

Most of the members of these poetry societies did not receive much education, and their knowledge of the history of Chinese literature is often stuck at a beginner's level. Most show a special fondness for Qing poetry, and Tang poetry, usually regarded as China's most magnificent, is not popular among them. If they don't read much, they are liable to elicit comparisons to a general store that doesn't acquire new stock for decades--"How can it sell anything worth buying?"

As for the poetry competitions these societies sponsor, because the topics are limited and everyone brings in reference books from which they borrow extensively, critics have been known to carp that "the poems sometimes end up sounding all alike." Even more to the point is that the topics are all too often weddings or funerals, gatherings of friends, or even current events, which give the poems a heavy political flavor. Hsu Chih-cheng, that old poet of Lukang, remarks, "Poems should express one's feelings, but now they are all written on topics like celebrating the 80th anniversary of the nation's founding or the birthday of some Taoist deity. What kind of poetry is this?"

Wang Wen-yen, professor of Chinese at Chengchih University, holds that there is nothing wrong with these competitions and notes that the whole idea behind the societies is to provide practice in writing poetry and to stir up enthusiasm for poetry. "Since ancient times, great works have rarely been created in the exam room, but rather have come out of the feelings imparted by one's own experiences. Still, getting together with fellow enthusiasts and creating is a cultural activity and a way to promote poetry."

Modernizing old societies

The truth is that poetry lovers needn't have high educations, but if poetry societies can establish links with academia, this may provide some cultural stimulation. Yet poets of the older generation tend to stress practical experience and criticize poetry professors for reciting theoretical mumbo-jumbo while not necessarily being able to write poetry well themselves. "It's like trying to teach someone how to swim in a classroom." On the other hand, scholars at research institutions, well versed in the famous poetry of history, feel that the work produced in these societies can't really be considered poetry at all.

There is, furthermore, the basic problem of the two sides literally not being able to understand each other. Because the Taiwanese dialect is similar to the original spoken classical Chinese, Taiwanese speakers can usually grasp the proper cadence of a line at first glance, and so many Taiwanese poetry enthusiasts are strong supporters of promoting the mother tongue. Yet while these elders want to pass along their methods, many of the young academics can't even understand Taiwanese. Meanwhile, the obstacle of Mandarin keeps the old poets from pursuing higher degrees. For example, once National Chungcheng University in Chiayi held a poetry appreciation activity in its cultural center, but only one member of the Chiayi Poetry Society, a mainlander, attended.

If the idea is to modernize, perhaps the place to start is with activities. Besides gathering to read the poems of their own members, poetry societies sometimes put on poetry writing and reading classes for outsiders, or hold riddle-composing activities for the Lantern Festival. But a generation gap plagues these societies. The young hope for a livelier atmosphere that will attract more people, but under the elderly's leadership the form of the activities rarely changes, and there is even a limit to the suggestions that can be made. "Old folk are very stubborn, and many have tempers like little children. They often scold us," one young poet says in confidence.

Getting classical poetry into people's lives

To look at it from another angle, is it absolutely necessary that members of these poetry societies compose poetry? If people are avid readers of poetry, "they needn't write poetry to be able to read it aloud." The Kaohsiung Classical Poetry Research Association led by Chien Chin-sung provides another way to approach poetry besides those offered by academia and most poetry societies. Its curriculum includes classes on poetry appreciation, philosophy, and Taiwan history. "The object isn't to learn how to write poetry but rather just to appreciate it--and through it taste some of the flavor of life."

They also advocate making classical poetry more relevant to people's lives, such as by uncovering ten steps of brewing tea in Su Dong-po's poetry, starting from the breaking up of tea leaves: "Mincing the body and grinding the bones releases the flavor." When the water is boiled, bubbles float to the surface one after another: "Fish eyes follow crab eyes." And finally, "See, smell, taste and touch. "

Last July they even held a poetry competition for children that mimicked the old civil service exams. Each contestant was asked to write a four-line poem extemporaneously and make a matching illustration. The Poetry Society has held a Tang poetry camp at Hsitzu Bay where they brewed tea and listened to poetry. The camp's layout was modeled on Tang dynasty military encampments, and they even held a traditional Chinese soccer match. The camp attracted many families and may well prove to be a good way to indirectly promote the study of poetry.

But what of these traditional poetry societies and their poet-members? What place can they be given in the history of Taiwan that will let them both read their verse and attract others to join them?

Delighting themselves and their listeners, old poets recite Tang poems with the original pronunciation.

In the 1920s there was an all-women's poetry society. Generally speaking there are fewer women poetry enthusiasts.

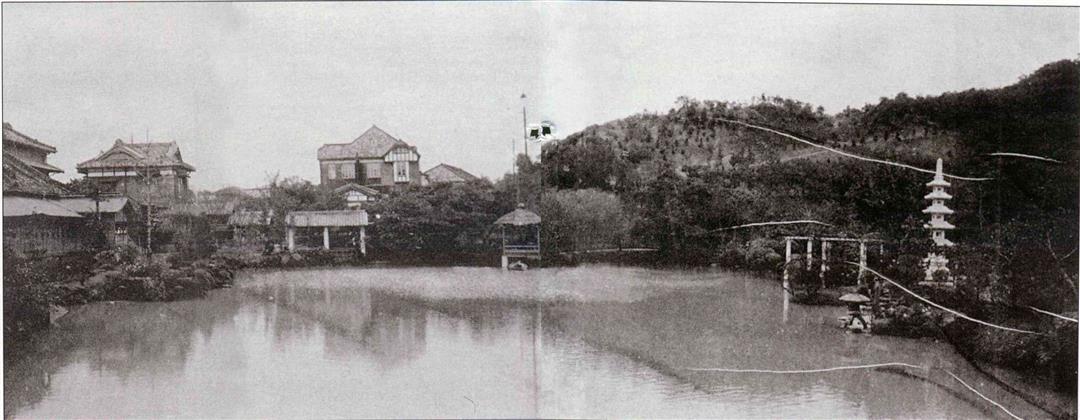

Yen Yun-nien, a mining magnate of the Japanese era, once invited Ocean Society poets to Lou Yuan, his villa in Keelung. (photo courtesy of the Yen Family)

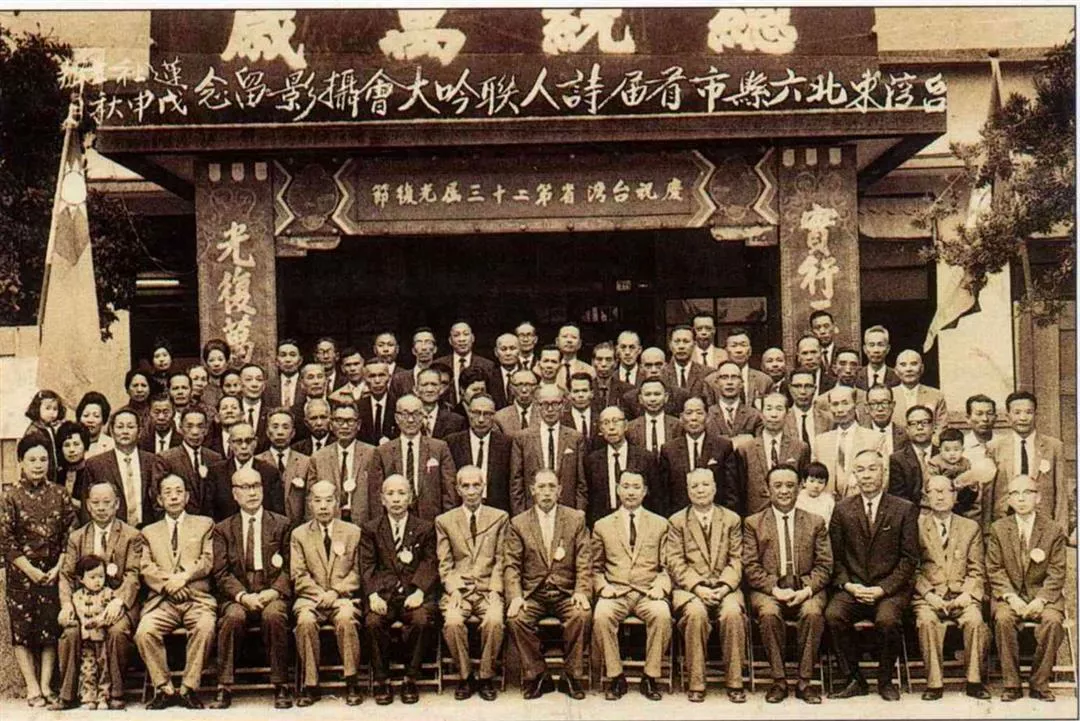

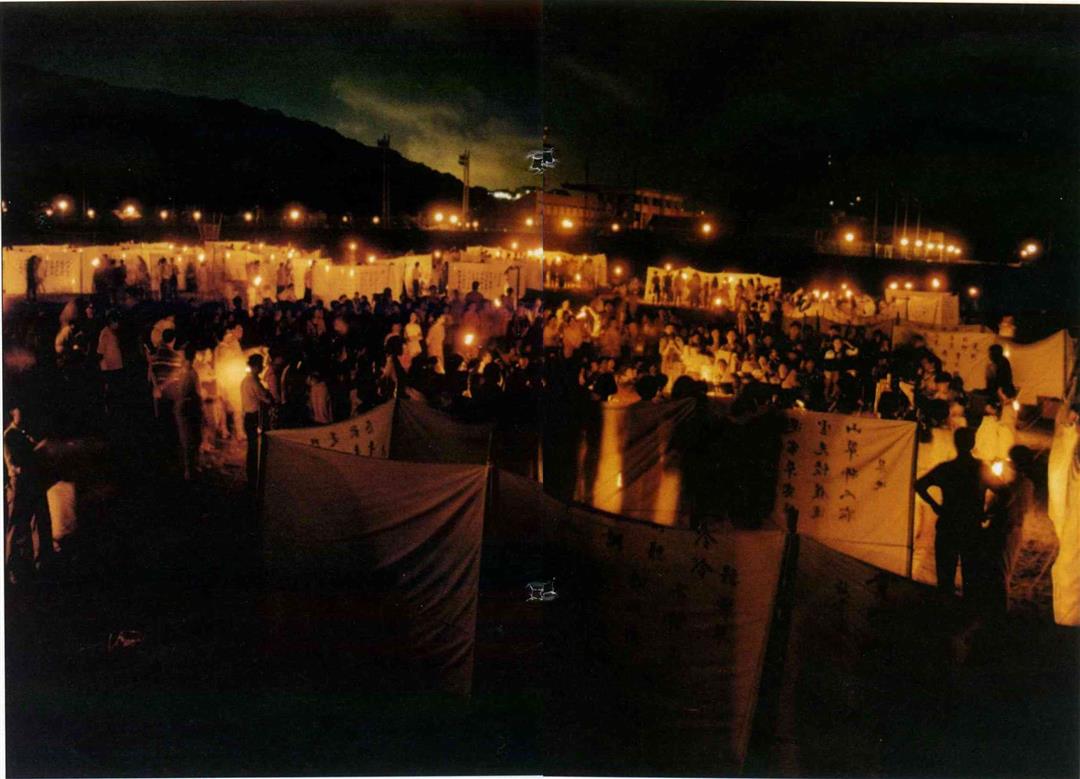

The societies often work together to hold big poetry readings. The photo shows one such gathering in 1968. (courtesy of Tsai Chiu-chin)

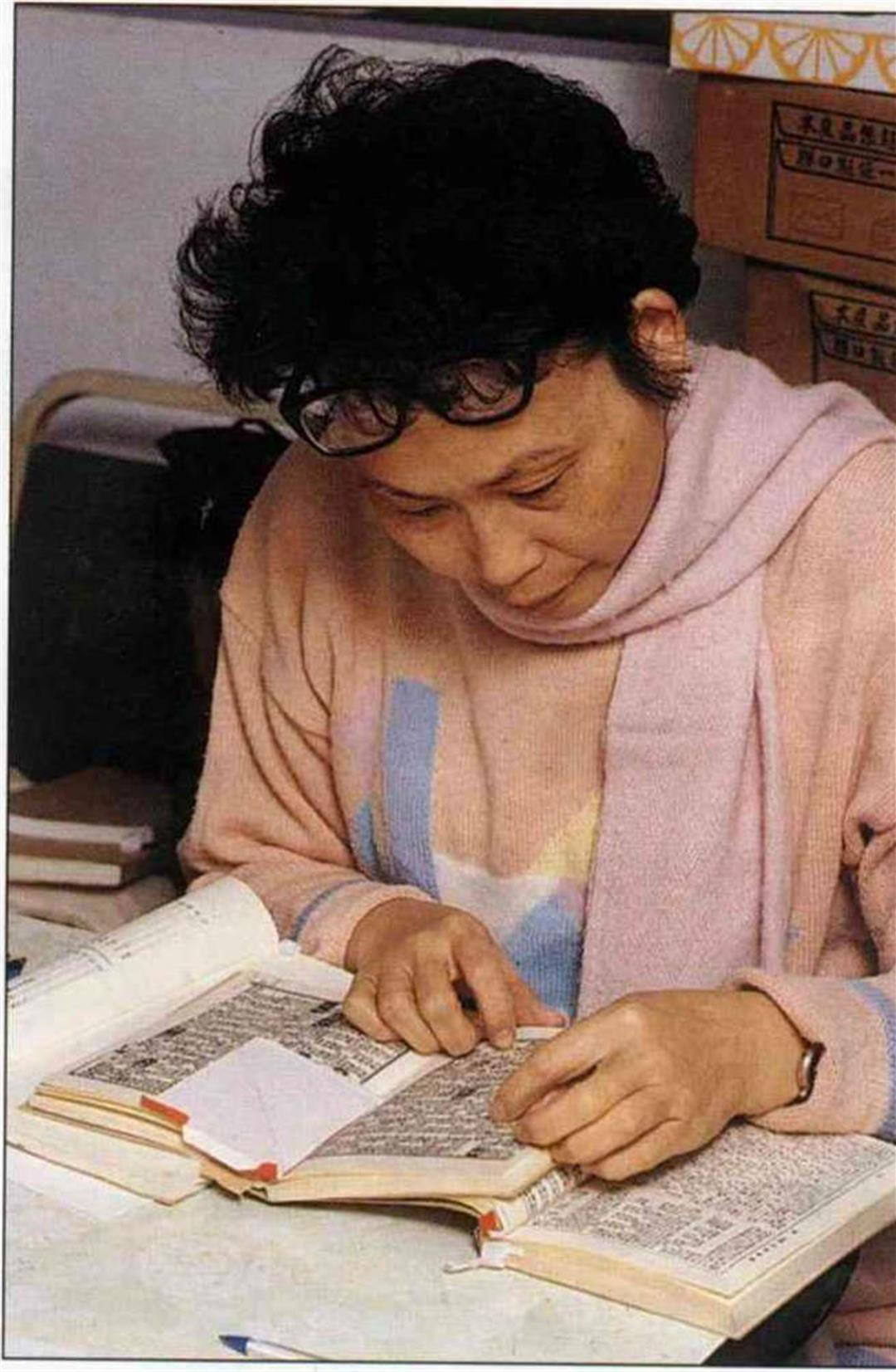

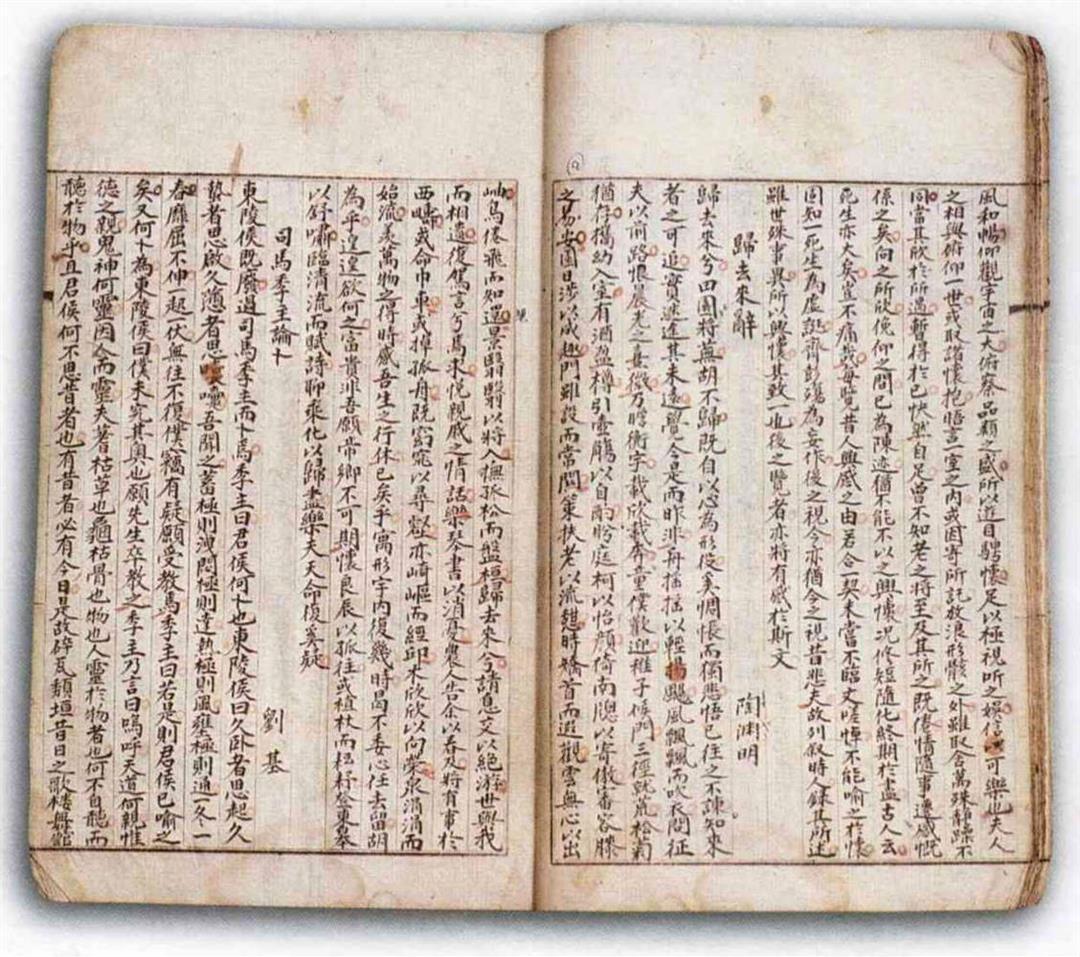

During the last years of the Japanese era, poetry societies in Taiwan to ok up where private village schools left off in passing along Chinese culture. A textbook from that era is spotted yellow from age.

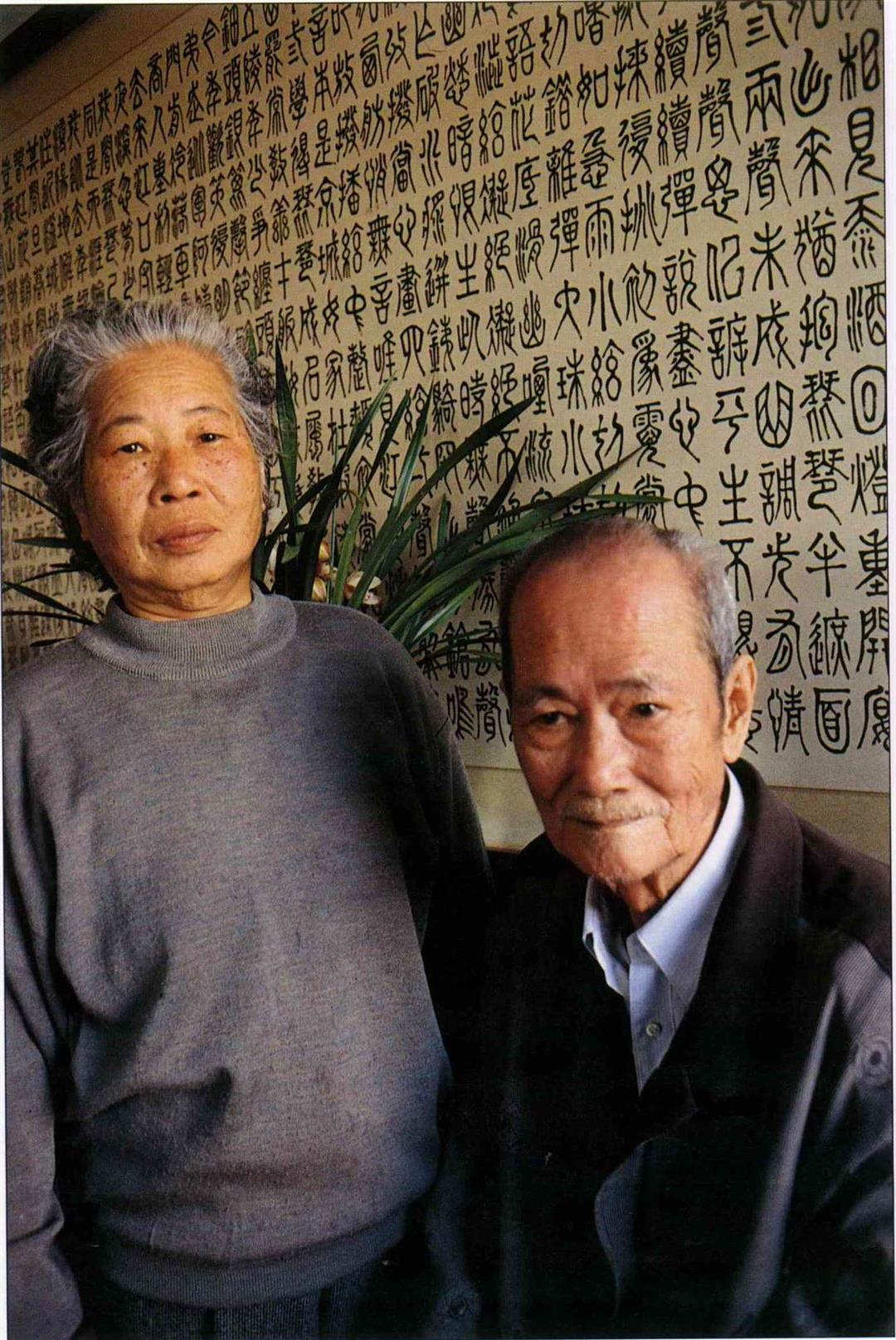

Hsu Chih-cheng (right), leader of Lukang's Wenkai Poetry Society, is an excellent calligrapher, and his study's wall is covered with his own work.

Chien Chin-sung, an associate professor of Chinese at National Sun Yat-sen University, has criss-crossed the province visiting poetry societies. He hopes to find some way to let the societies enjoy a miraculous renaissance.

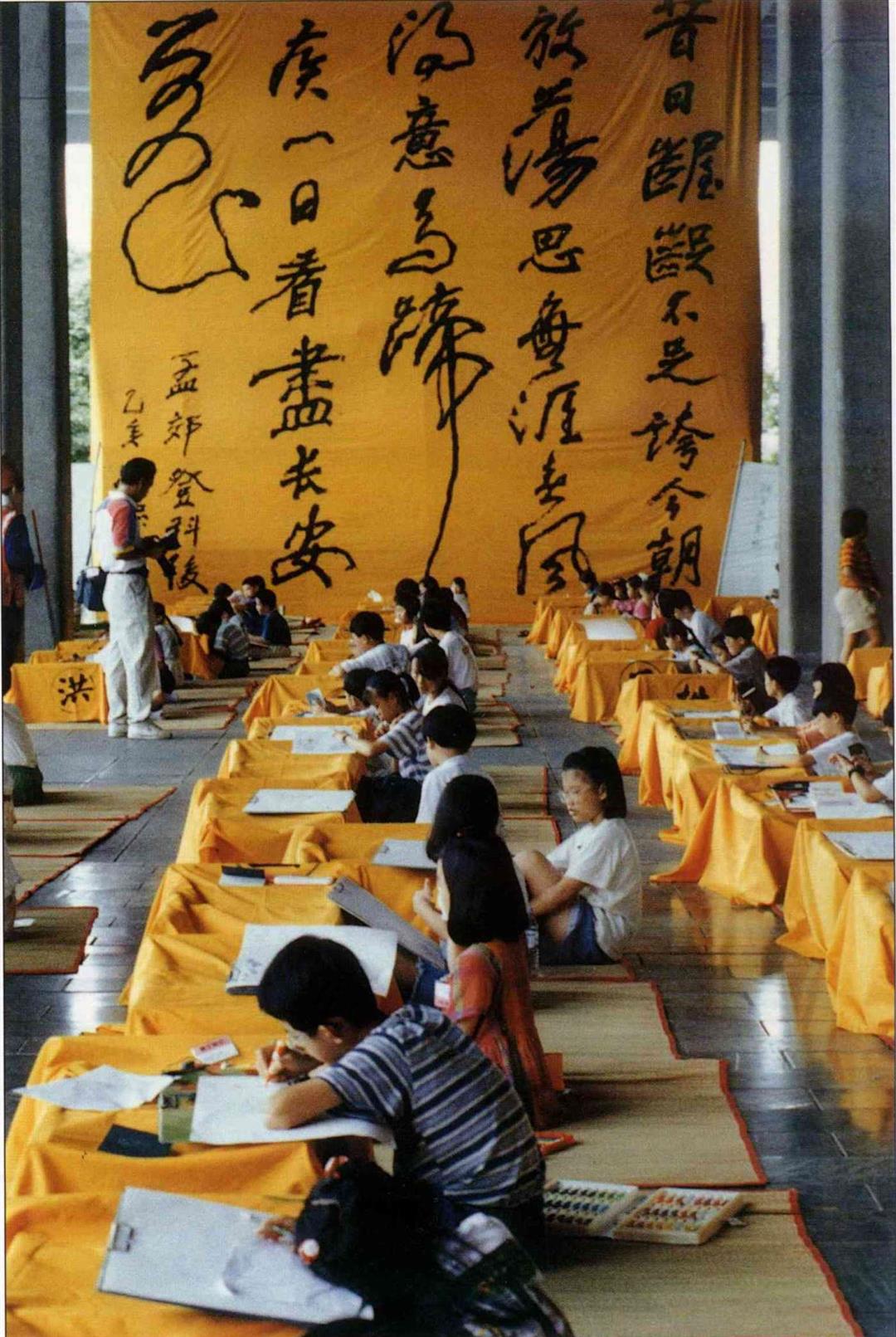

Among the screens raised at Kaohsiung's Hsitzu Bay, people sip tea and listen to poetry. How romantic! (courtesy of the Kaohsiung Classical Poetry Research Association)

For a children's poetry competition imitating the Chinese civil service exams of history, each contestant must write four outstanding lines of verse and draw a matching picture. The atmosphere is even tenser than during the joint entrance exams for high school and university. (courtesy of the Kaohsiung Classical Poetry Research Association)