To many people in Taiwan, Africa is a vast, mysterious and backward land, a land redolent of the unknown and yet full of promise. Five centuries ago its magnetism drew Chinese navigators to its shores on voyages of exploration. In the seventeenth century adventurous Chinese settlers arrived there and began putting down roots as they built new homes in a foreign land.

According to figures compiled by the Overseas Chinese Affairs Commission, the majority of the 31 million overseas Chinese living abroad as of the end of 1989 were resident in Asia, with fewest of all in Africa. The overseas Chinese communities in Africa number only 92,400 people in all, accounting for just 0.3% of the total overseas Chinese population. Most of these live either in Mauritius, the Malagasy Republic, Reunion or the Republic of South Africa.

With 15,000-odd people, the overseas Chinese community in South Africa ranks as the fourth largest on the entire continent, despite being historically the oldest established. In Transvaal Province (one of the four provinces in South Africa, the others being Cape Province, the Orange Free State and Natal) the Chinese Association has been collecting historical data since 1981 on the South African overseas Chinese community as the basis for a forthcoming book. "It's like doing a jigsaw puzzle, the clearer the picture grows the more exciting the game becomes!" says Liang Jui-lai, a member of the research team. Three researchers have interviewed over 100 members of the Chinese community and searched government records, and about 300 photographs have come to light from both official and private sources.

But there are difficulties to contend with. According to Yeh Hui-fen, another researcher, the biggest problem is that the older generation are dying off. People of 70 or above were targeted for interview, until they discovered that Chinese of this vintage were few and far between. Many of those still alive have patchy memories, and what little information can be gleaned may turn out later to be questionable or just plain wrong. Furthermore, although the researchers themselves are genuine ethnic Chinese, most of them don't have a good command of the Chinese language. In case of difficulty they have to communicate with older people through an interpreter. Lack of historical data also places obstacles in the way of completing the jigsaw.

Yet among such records as have been collected, it is sometimes just possible to glimpse the face behind the veil. . . .

According to statistics kept by the ROC consulate-general in Johannesburg, there are currently over 15,000 overseas Chinese and persons of Chinese descent in South Africa. Two-thirds are persons of Chinese descent, most of whom live in Cape Town (around 3,300) and Johannesburg (around 9,000), with the rest scattered among other towns and cities of South Africa and the tribal homelands.

Records of Cape Province Government show that Chinese people lived there as early as 1660, although no further details are given.

More precise records document a small early influx of Chinese to South Africa in 1815, with the arrival of carpenters and bricklayers contracted to work in Cape Province. These 13 bricklayers, 10 carpenters and one painter all signed three-year work contracts.

Then in 1870 a wave of emigrants from southern China left their strife-torn homeland for a new life overseas, making their way to South Africa via Mauritius and Madagascar. From 1891 onwards more and more immigrants arrived from places such as Shunte, Nanhai and Mei-hsien in Kwangtung province, mostly to work as skilled laborers or as small traders. The majority of South Africa's present-day overseas Chinese community are descended from these.

In those days the sea voyage from China to South Africa took three to four months. People often died en route due to poor hygiene and lack of medical equipment on board ship. It was not a happy experience.

During the Boer War (1899-1902) a rich goldmine was discovered at Witwatersrand, in the Johannesburg area. This was eagerly developed by the Boers, despite a shortage of efficient local labor.

With the end of the war, the government of Transvaal Province decided to bring in Chinese laborers with the help of British connections with the Chinese government. Thus in May 1904 a protocol was signed between the British Foreign Office and the Chinese Minister to Great Britain, Chang Te-i, in which it was agreed to transport Chinese laborers in return for adequate guarantees for their safety.

The first Chinese consul-general to South Africa, Liu Yu-lin, arrived at Johannesburg in 1905, marking the establishment of consular relations between the two countries.

Thanks to their industriousness and efficiency the Chinese workforce soon nearly doubled South Africa's gold output, and the number of Chinese mineworkers eventually peaked at just over 53,000. As far as the Chinese were concerned, the whole of South Africa was one gleaming mountain of gold. Between 1904 and 1907, a total of 63,000 Chinese workers were transported in 34 ships to work at six different mines in the greater Johannesburg area. But the influx of large numbers of foreigners drew hostility from the local community. The South African government introduced strict controls, only permitting the Chinese to work as coolies in the mines; trading licenses were refused and Chinese were not permitted to purchase real estate. Moreover they were only allowed to work at certain designated places. All Chinese had to carry a government-issued pass, which they laughingly referred to as a "dog licence." But they could always go on strike in protest at working conditions and low pay, so the South Africans had no choice but to send the Chinese back home.

The first batch of Chinese workers was sent home in 1907, and by 1910 all Chinese mineworkers had left South Africa. Did any slip through the net? So far the Transvaal Chinese Association has discovered no evidence of Chinese goldmine workers having settled down in the country.

Beginning in the 1920's a certain number of Chinese discreetly entered South Africa from the mainland and lived a hard life under assumed names in order to disguise their illegal presence in the country. Later arrivals received ample help from their pioneering countrymen, and modest Chinese communities gradually took shape.

With the outbreak of war between China and Japan in 1937, the South African overseas Chinese community did its best to assist the Nationalist Chinese war effort. Women even sold their jewellery to set up an armaments fund. The Chinese in far away South Africa still retained warm thoughts for their homeland in its hour of need.

South Africa's introduction of apartheid in 1948 condemned the country to international isolation. This policy of racial segregation restricted the freedom of colored people to reside, travel and marry. Under the Group Areas Act, Whites, Blacks, Asians and Coloreds had to live in designated areas and could not buy or own real estate outside their designated area.

At first the Chinese in South Africa were classed as Asians with restricted rights and status. Since Chinese were legally barred from intermarrying with Whites, they had to go back home to find a wife. This was usually combined with a trip back home to purchase farmland with the money earned working in South Africa. Accountant P'an Kuo-hsuan recounts with a smile how his grandfather went home to China three times--and brought a new wife back with him each time! In due course ROC-RSA relations progressed to the point where the two countries exchanged ambassadors, until in 1985 South Africa officially announced that Chinese were to enjoy equal status with Whites. Overseas Chinese still have to obtain permits for a few things, but they are generally treated as Whites as far as residence, employment, schooling and the use of public amenities are concerned.

In the old days, Chinese working in South Africa belonged to one of two communities, being either Cantonese-speaking natives of Nanhai, Shunte and Panyu counties along the lower Pearl River, or Hakka-speaking natives of Meihsien in northern Kwangtung province. There are about 12,000 of these "established" overseas Chinese.

Most of these people live in East London, Port Elizabeth, Durban and Kimberly. They tend to be shopkeepers running laundries, butcher's shops or general stores, although some are farmers, cooks or carpenters. The majority keep general stores or run restaurants. The older ones worked their fingers to the bone to give their children a better education and free them from enduring the hardships they once knew.

Rodney Leong Man, Chairman of the Chinese Association of South Africa, points out that local state schools used not to be open to Chinese, who had to turn to private education. Catholic and Anglican schools agreed to accept overseas Chinese children, but their fees were high. Chinese parents just gritted their teeth and put up with it because their first wish was to get their children into college. Thus the second- and third-generation overseas Chinese have produced numerous doctors, lawyers and accountants who enjoy a markedly better social position and standard of living.

In the old days members of the overseas Chinese community tended to intermarry with each other and so maintain their Chinese language and cultural customs. With the fall of the mainland in 1949 it was no longer possible for overseas Chinese to "import" wives from China itself, so they married women from other clans. "Unless the parents speak Chinese at home, their children lose the chance to learn the language naturally," sighs Hsieh Jung-ch'un, a member of an extended three-generation household. This is how a culture gap has arisen which means that only a minority of third-generation overseas Chinese still speak a Chinese dialect. Even fewer can read or write Chinese characters.

As happens with overseas Chinese elsewhere in the world, the older generation despair over their children's adoption of "foreign ways." "Such a tragedy!" is all T'an Chih-ch'iang of Port Elizabeth can say about his children's inability to speak Chinese.

In contrast to these "established" overseas Chinese are the more than 3,000 "new overseas Chinese" who have arrived from Taiwan in recent years, most of them to invest and engage in business activities. Generally speaking, they enjoy better economic circumstances.

The team researching into the history of Chinese settlement in South Africa have brought to light much concrete evidence of the past. But gaps still remain in the documentary record. As Yeh Hui-fen points out, about 2,000 overseas Chinese left South Africa in the 1960's and '70's owing to apartheid discrimination and resettled in Australia, Canada and the United States. They might have valuable photographs or historical materials in their possession. Liang Chao-li, a prime mover behind this project, pleads: "In order to help the younger generation understand the lives of the previous and earlier generations of overseas Chinese, I hope they will provide materials to help us make our projected book complete."

[Picture Caption]

Cape Town was the first way station for Europeans arriving in South Africa, and it is commonly said, "If you haven't seen Cape Town, you haven't seen South Africa." (photo by Arthur Cheng)

South Africa's gold mines once attracted Chinese in search of wealth. Their diligence and endurance soon doubled the mines' output. (photo courtesy of the compile rs of A History of the Chinese Community in South Africa)

Johannesburg's Chinatown employs many South African Black workers.

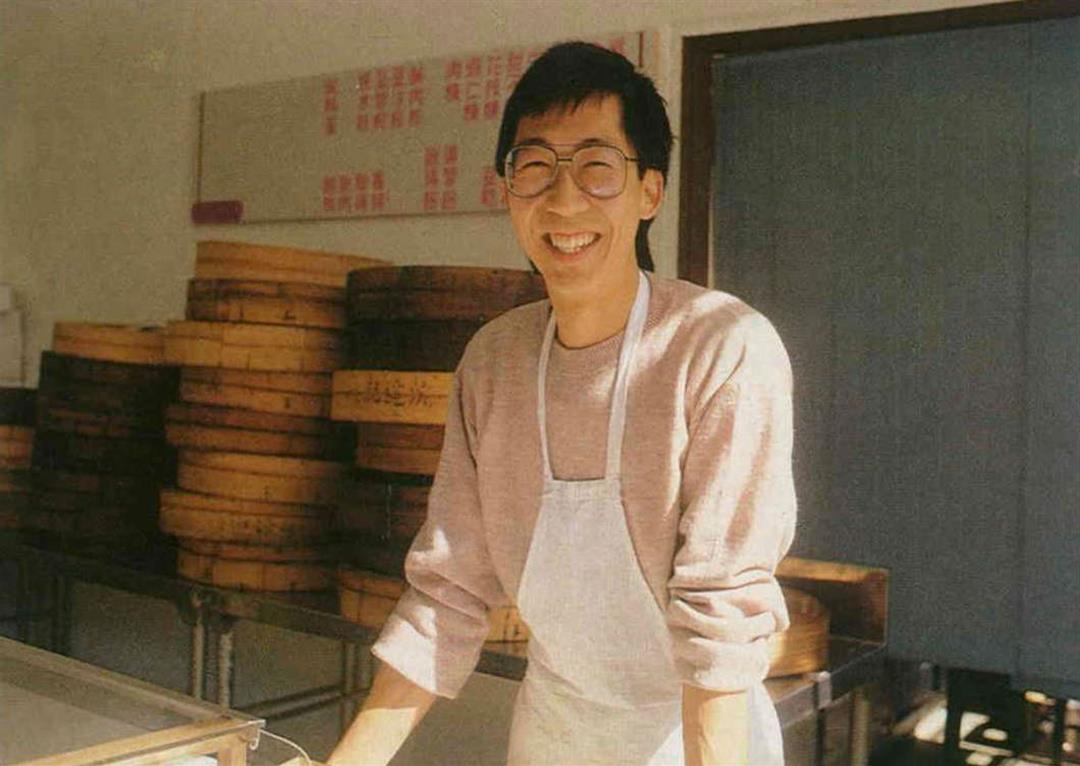

"Sorry, I don't speak Chinese well!" says an assistant at a Chinatown steamed dumpling and beancurd shop. South Africa's second and third generation ethnic Chinese normally speak English better than Chinese.

At a Chinese-financed ball-bearing factory in East London, technicians form Taiwan show local female workers improved techniques.

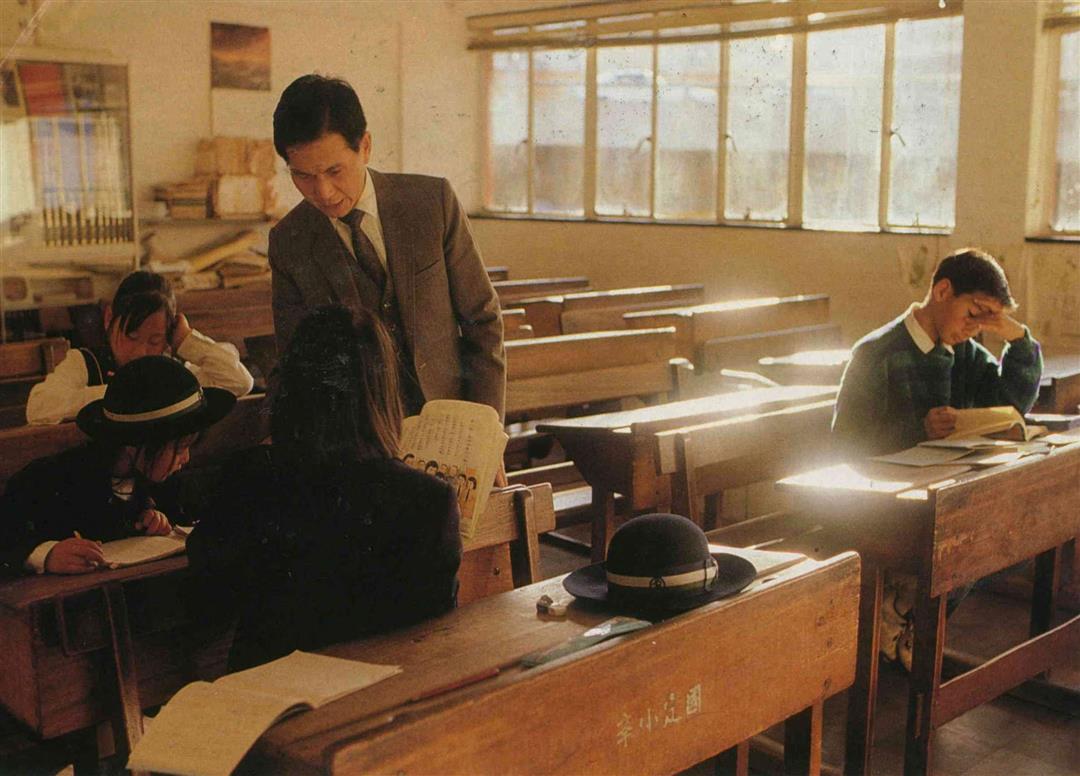

Ethnic Chinese primary schoolchildren in Johannesburg can take an extra- curricular course after school with a Chinese teacher at the local Chinese Cultural Centre, an excellent chance to learn Chinese.

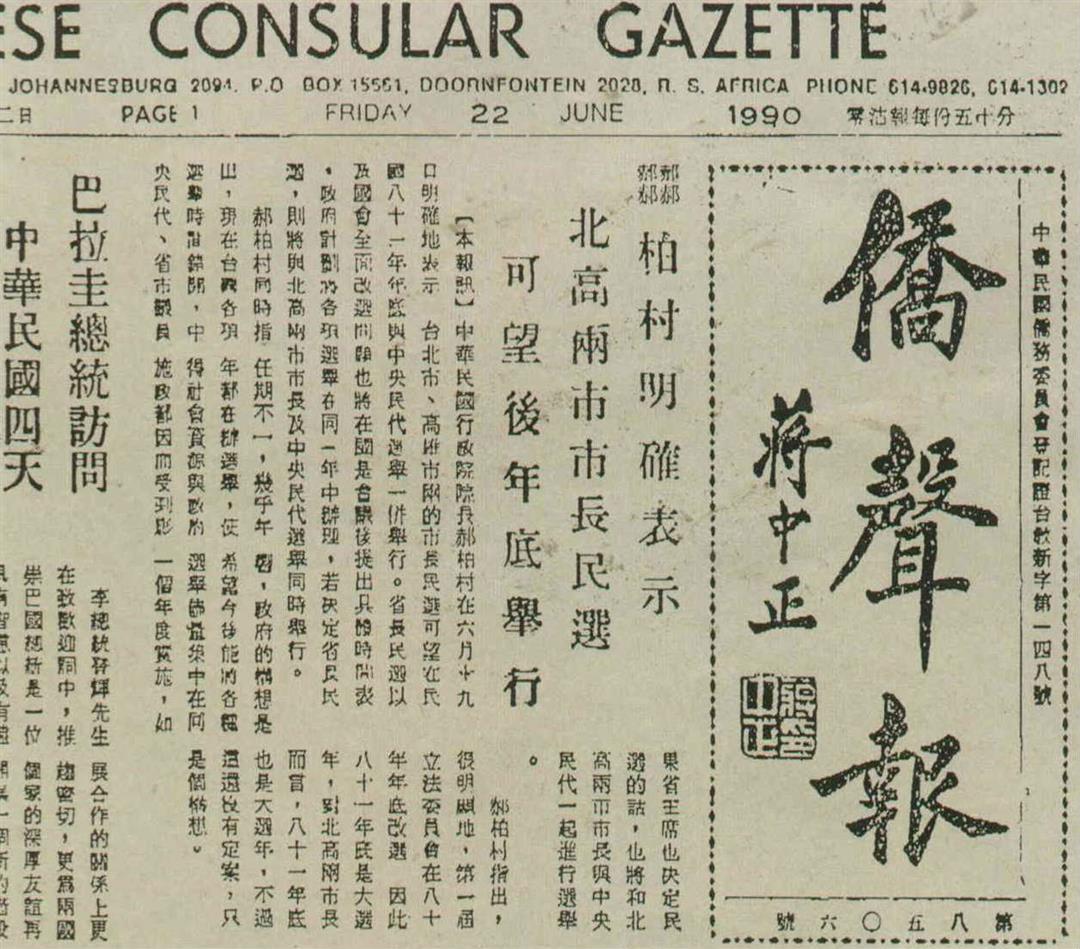

The typefaces for this overseas Chinese newspaper were brought over from Taiwan. In case they ever run out, four small characters can be used to replace one large character.

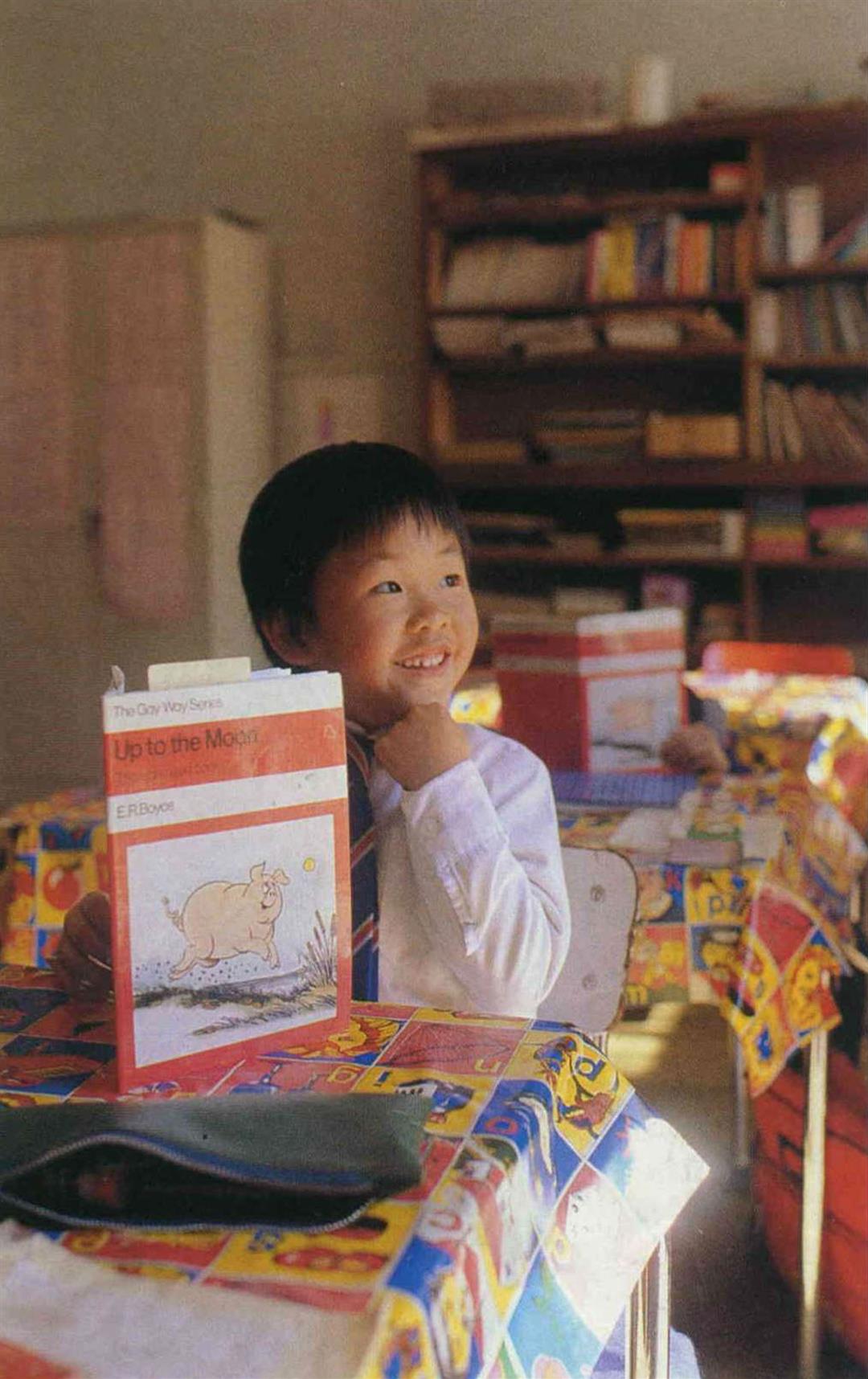

The Chinese public school in the South African capital, Pretoria, was established purely for ethnic Chinese students. English education is provided initially at the kindergarten stage to help the pupils feel more at home.

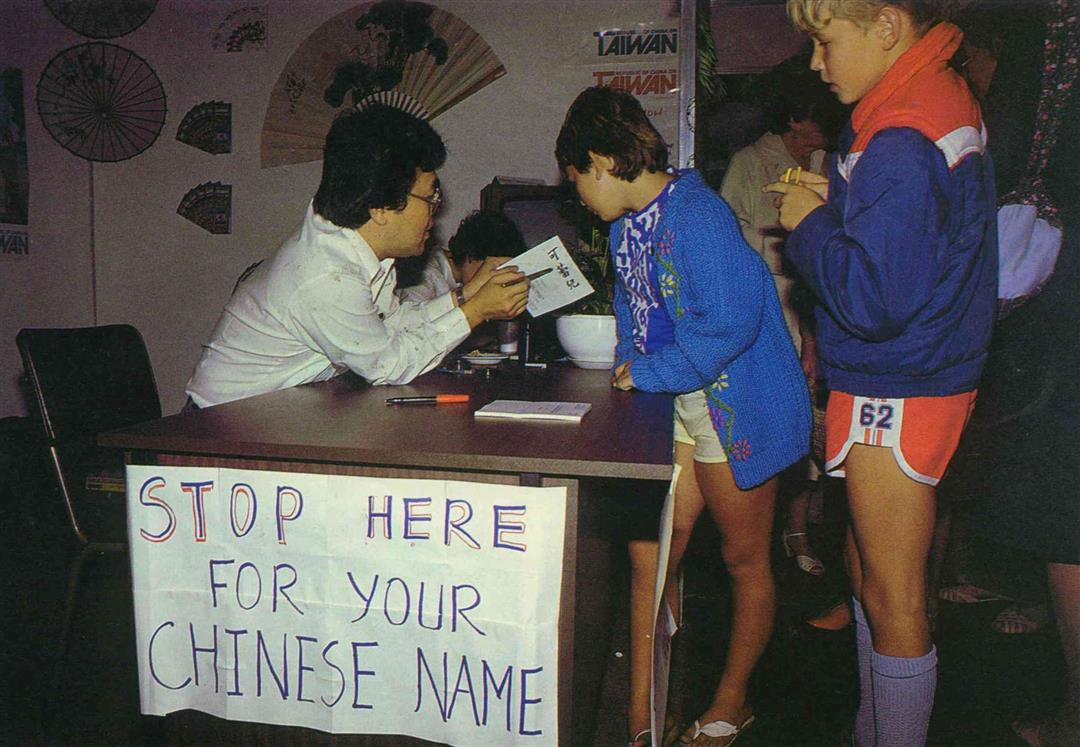

Choosing Chinese names for your foreign friends helps you make friends quickly in strange parts, and South Africa is no exception. (photo by Arthur Cheng)

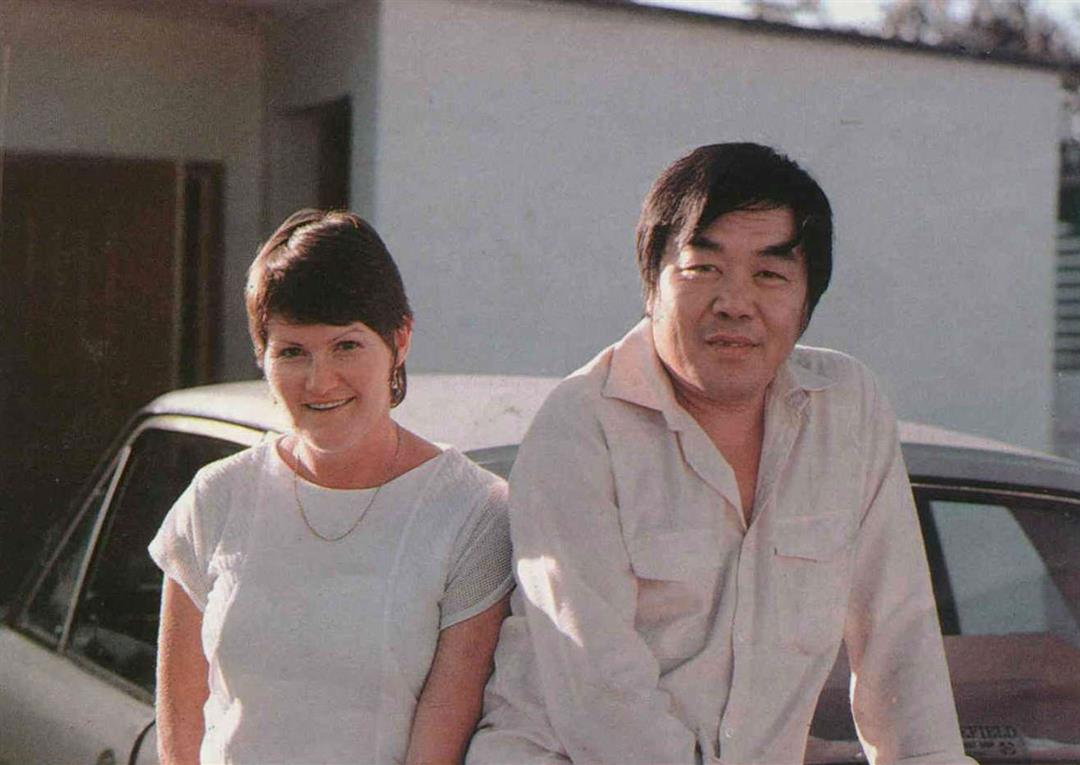

Mixed marriages are fairly common in South Africa. (photo by Arthur Cheng)

South Africa's gold mines once attracted Chinese in search of wealth. Their diligence and endurance soon doubled the mines' output. (photo courtesy of the compile rs of A History of the Chinese Community in South Africa)

Johannesburg's Chinatown employs many South African Black workers.

Sorry, I don't speak Chinese well!" says an assistant at a Chinatown steamed dumpling and beancurd shop. South Africa's second and third generation ethnic Chinese normally speak English better than Chinese.

At a Chinese-financed ball-bearing factory in East London, technicians form Taiwan show local female workers improved techniques.

Ethnic Chinese primary schoolchildren in Johannesburg can take an extra- curricular course after school with a Chinese teacher at the local Chinese Cultural Centre, an excellent chance to learn Chinese.

The typefaces for this overseas Chinese newspaper were brought over from Taiwan. In case they ever run out, four small characters can be used to replace one large character.

The Chinese public school in the South African capital, Pretoria, was established purely for ethnic Chinese students. English education is provided initially at the kindergarten stage to help the pupils feel more at home.

Choosing Chinese names for your foreign friends helps you make friends quickly in strange parts, and South Africa is no exception. (photo by Arthur Cheng)

Mixed marriages are fairly common in South Africa. (photo by Arthur Cheng)