Bo Yang often says that he is a rubber ball-the harder you throw him down, the higher he bounces up. But I think that he is a current of water from canyons deep within the mountains, full of self-confident vitality, pushing at rocks and pulling at earth, only gaining in strength from exposure to fierce rains, and ultimately flowing into a sea of knowledge and strength.

Q: Your memoirs could be described as a tale of blood and tears. How did you feel as you orally recounted these memories? How can your life, which has more suffering but also more achievement than most, enlighten readers? Is there something else you would like to say to your readers, or friends of your generation, the younger generation, or even the "new new youth"?

A: The way I feel about these incidents now as I recall them is very different from how I felt when I was experiencing them. In one of his poems, Du Fu wrote, "As I enter the gate, I hear wails; my son lies dead from starvation." Returning from distant travels, neither happy faces nor passionate embraces welcomed him. A lonely figure in front of a ramshackle house, he heard sobbing from inside. He bounded through the door to discover his youngest son lying dead on the bare planks of the wooden bed. Grouped around the small corpse were the rest of his family-as thin as rails, dressed in rags, hungrier even than his dead son. Did Du Fu take out buns from his traveling bags for everyone to enjoy? Did he pull out some silver coins and urge his family members to go and buy some food? Or did he stand there dumbly, his mouth agape, because he had spent all his money on his long travels and hadn't eaten himself for two days, having only been able to keep himself going with visions of a homecoming feast? We don't know the details, but we know this fact: Du Fu wrote these ten simple characters long afterwards, as a recollection of that moment of suffering. The sparse description conveys great human suffering, the worst tragedy that can befall a father. Yet his was just a weak little voice amid the thunderous flood waters of society. At the moment Du Fu entered his home, he couldn't write lines of poetry like these. When he could write them, he had already calmed down. Though he may still have been shedding tears, he would have nonetheless been in complete control of his emotions. When I orally recounted my memoirs, Dr. Chou Pi-se was sitting across from me. Occasionally I would hear her sigh, but she didn't say much. When I paused, she drank tea. My feelings were much like Du Fu's when he wrote those two lines of poetry. I coolly and clearly described events, as if they had happened to someone else. God has given me more than my share of hardship, and so He has also made me better able to endure and transform it. Each memory is like a wisp of smoke, under which you can see the scenes and people of an earlier era, and practically even hear its sounds. Under these wisps I am very calm and enjoy a sense of accomplishment. Though Dr. Chou is much younger than I and has had very different life experiences, she could completely understand.

Passing the torch

You said that I have suffered and achieved more than most people! I appreciate your praise, but I beg to differ. My troubles haven't been out of the ordinary. Do you know how many people died because of war or starvation or at the hands of other Chinese? Do you know how many people were crippled, how many homes were broken, how many people cried and suffered in jail? Mine was a generation deserted by God, trampled by tyrants, exploited by those with overweening ambition, and abused by oppressive officials. If I was forced grudgingly to say that I have had some success, it has only been in maintaining my health and spirit up to now. And this can't really be called an accomplishment, for it is just the result of changing times and God's mercy, which have allowed me to have a normal life in a democratic country. So I don't know what to tell the younger generation. I can't tell them, "Don't love your country." But I know that you can end up suffering as a result of your patriotism. I can't encourage the young to lie, yet telling the truth can cause people to tremble with fear. This is my greatest regret. I can only tell the young that my generation's time has gone, but we have passed on a legacy of democratic government and economic prosperity. This is a golden age unlike any ever seen before in the history of China. The people of our generation can die in peace. As we pass the torch to the next generation, we should reflect upon what kind of society it is that we are leaving them. Is it one with more freedom and more equality? Or is it one where the White and Red terrors could be revisited? Is it an affluent, prosperous society, or one where our workers have to go abroad to find jobs?

Q: Your life has spanned traditional China's passage into the modern age. How do you look at classical Chinese culture and Western civilization? The dark side of Chinese culture is closely connected to all the suffering you have endured. Did this have an effect on the views you expressed in your best-known work, The Ugly Chinese, which describes the dark side of Chinese culture and human nature?

A: A poet [Kipling] once said "East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet!" At first I didn't believe in stressing the differences between East and West for the reasons expressed in the Chinese expression, "People's minds are alike, and from similar minds come similar ideas." This was a starting point for how I looked at things in the first half of my life. But in the days since, I have gradually revised my way of thinking. While people may have similar minds, they don't necessarily reach the same conclusions with them. Cultural differences can cause different conceptual systems to arise from the same basic human feelings. At the beginning I felt that Chinese culture's dark side grew out of the political system and political thinking, but after I deeply examined it, I discovered that our culture's dark side comes from lacking a conception of human rights, which has caused the Chinese to be concerned only with face and not with dignity. Someone who wants face is constantly taking measures to cause others to lose it while they keep it. But someone who has dignity must show respect for other people's dignity before he can establish his own. And so the basic thinking of "the emperor is respected and his inferiors reviled" has resulted in a culture where the ruler and government officials have face but where ordinary people have none. This kind of culture will surely become decadent, and any kind of political system built on it is sure to be warped.

Still the "ugly Chinese"?

Then there is an even more serious problem: More even than lacking a conception of human rights, our "cultural genes" lack an ability to judge beauty. Up to the 20th century, I have my doubts about how important "beauty" has been in Chinese culture. In other words, our culture became ugly because we didn't know what beauty was. Binding women's feet not only disfigured Chinese women's bones but twisted Chinese minds into somehow thinking that bound feet were beautiful and that natural feet were ugly. It was all due to the lack of an aesthetic sensibility. Not knowing what is beautiful, we can't and won't seek it, express it and praise it. Even now schoolboys will disparage schoolgirls for "loving to look pretty." Making oneself beautiful should be praiseworthy, but to young minds it becomes something negative. In reality, the person who attacks aesthetes has a passionate love of beautiful women, but daunted by the prospect of taking on the whole culture, he won't dare to admit it or talk about it. This is our "pickling pot" culture. The suffering I endured since I was young has of course had a big impact on me, but it has also been a lot of help in getting me to think constantly about the primary causes of this suffering. One of these is the heinous tradition of "mistreating others the way we were mistreated"; it's our mother-in-law-daughter-in-law culture. This is a vicious cycle: You bound my feet, so I'm going to bind her feet. Its whirlpool-like effect pulls people under. And to jump out of this whirlpool, we need the freedom, equality and human rights of Western culture (although Western culture isn't without its faults too).

Q: Many of the "bad guys" who seemed to be badly lacking humanity in your book are still alive. In writing this book, did you have any misgivings? What do you hope to achieve by exposing these people? Some of these people still hold high positions. How do you feel about that?

A: In one of Erich Maria Remarque's novels, a mild-mannered shopkeeper serving as a guard at a concentration camp stomps to death a Jewish prisoner without giving it much thought. When he leaves the camps, he becomes once again a warm and friendly shopkeeper who is very courteous to everyone. The people who have hurt me, including my stepmother, did so because it was as if they were in concentration camps themselves. Of course, some people who have a basically evil nature will become only more vicious. But most people are like that shopkeeper Remarque described, and might be quite lovable individuals in other situations.

Not seeking revenge

I used to think a lot about exacting revenge, which is the hero's way of getting satisfaction. But since the taking of revenge came in conflict with my later ideals, I have done my best to restrain myself, and finally my original nature has yielded. Purely from a cost-benefit perspective, a revenge- oriented society will make rulers cling to power until the bitter end, meaning that more violence would be needed to unseat them. This is what the 5000 years of Chinese history is all about. It's not that I'm hard to scare (God has given me an adrenal gland, which is His way of telling me to be scared). It's just that I react slowly to authority, and although I am afraid, neither being assassinated, nor being arrested, nor being jumped in a dark alley is a threat to me anymore, because how many more years do I have to live anyway? "From ancient times to the present, who hasn't died or won't die? The important thing is to leave something behind!" An attack will just firm my resolve. To my grave I will adamently believe that society can be righteous and the human heart can be reasonable, and I am not afraid that day will come too late. With the few years I have left, there are too many truthful things I want to say-where is there time to lie? I have just recounted what has actually happened to me, and I haven't made any judgments. I will leave those to others who follow. I have always held romantic notions about things, so that my family calls me "an old innocent." It's important to remember that the secret police and any movement of terror always need the support of a tyrant. In eras where there are no tyrants, secret police have no power to indulge in atrocities and abuse power, because public opinion will put a stop to it.

Q: Disadvantaged by the environment of your childhood, how have you managed to transcend it and achieve such great learning? Do you have any unusual methods of study that could be used by those who also missed out on a good educational environment when they were young? When you encounter obstacles how does your personal philosophy allow you to maintain your sense of self and not buckle under? And when you pass these obstacles, how should that affect your view of the world? Has it allowed you to avoid being consumed by a burning desire to exact revenge upon those who wronged you?

A: The truth is that I'm a very ordinary sort of fellow, not someone who has harbored a great ambition since childhood to work on behalf of some great cause. And I'm not just being modest. Yet there is a story I can tell that might be illuminating. A frog fell into a deep rut left by a truck, and called out to his companions, who heard his calls and came quickly to help. Unfortunately, no matter what they tried, they couldn't pull him out. Finally, they just gave up. The next morning, they returned to the same spot, expecting to find their friend's corpse. Instead they found him jumping hither and thither in the grass and singing a joyful song. They couldn't help but ask, "How did you manage to jump out?" And he responded, "I had no choice-a huge truck was coming." I'm just like that frog. Fate and character, like two long whips, have constantly been forcing my moves. It's not that I've wanted to demonstrate my technique at jumping out of truck ruts. It's just that after getting pushed into the rut, I had no choice but to jump out of it.

Reading everything

From the process of my maturing, you can see that my knowledge is very limited. First of all, I didn't have a great upbringing. My father was rarely home and my stepmother didn't like children. My life has been full of terror and tragedy. Moreover, I didn't have a lot of time to peacefully study at school, I didn't like classroom learning, and I didn't have a benevolent teacher who nagged me to keep at my studies. And my own method of studying (hardly worthy of being called a "method") is just to read: any books I can understand, and even books I don't understand. I like to read them all, and don't read with any express purpose (except when I read those two English essays for the exams). And I read without any plan. For me reading is my greatest source of satisfaction. Not only do I read sitting on the toilet, sometimes I stay in the bathroom long after finishing what I came to do, all because I don't want to have to stop reading. And I even read and walk at the same time. When the Independence Evening Post was on Taipei's Chang-an Road, I would read on the way to work. Once I walked smack into a telephone pole by the Liukung Aquaduct on Hsinsheng South Road. As for the content of the books, sometimes they move me and sometimes they trigger my skepticism, but I always feel that I have absorbed every word as a kind of nutrition that has helped me grow. Unfortunately, I haven't read those books that people pore over for years to gain some sort of expertise, so I lack skills to make a living. I am very envious of those people who have had easier lives. It isn't as if they don't have their own troubles and haven't suffered. The difference is just to the extent of their troubles and their knowledge of suffering. Betrand Russell once said that no people in jail are smart, which is clear from the simple fact of their being in jail. And so I don't think that I am qualified to counsel young people on the proper way of doing things, because if they heed my advice, they may end up in jail. As for what I personally revere, I believe that one must constantly try to uplift oneself and grow. To put it more concretely: keep reading and absorbing, eating your meat and your vegetables, so that you can turn them into muscle and spirit. Intellectuals often sigh that they have talents but are ignored. The question is, if you got recognized, would your talents be enough for the job? Know yourself so that you don't end up suffering from "30-year-old's Alzheimer's disease." That's most important. I think that if you really are good, you'll get recognized.

One of my faults is that I never talk about the past, unless someone starts talking to me about it or I am writing my memoirs. Regarding past glory, some people can go on about themselves ad nauseam, but there wasn't anything glorious in my past. As for what was humiliating, talking about it will make me angry. And I'm quite selfish and don't want to be engulfed by hate and don't want it to govern my emotions, so I turn it into a little wisp of smoke. I can't stop loving the world of friendship and feeling, so I don't have enough energy left over to hate.

Many loved ones

Q: What has made you happiest in your life? What are your regrets? Who do you love most? Is there something or some person that you despise most? Of your work, what are you most satisfied with?

A: The happiest things in life, as far as I'm concerned, happen all the time in the normal course of things. Our family has something joyous happen every day: In particular, when we leave the house, we always discover that we've lost something, and look for a purse, or a bag, or a wallet, or spectacles, or house keys, or car keys, or an identity card, or an insurance card, or an ATM card or whatever, and this becomes a big deal, with everyone in an anxious panic, desperately trying to figure out how the thing got lost in the first place. This is especially so when trying to find our cat, who is called "Bear." He rarely strays from the house, but since we usually haven't a clue where he went, we turn the house upside down and go calling everywhere, as if some great disaster had occurred. And every time, without fail, we end up finding whatever we lost, and so experience great joy every day.

As for whom I love the most, I'm sure that you can predict the answer: my wife Chang Hsiang-hua. But I should also mention some people who have been very good to me, such as Mr. Wu Wen-yi, who brought me to Taiwan; Mr. Sun Kuan-han, without whose help I couldn't have struggled through ten tough years; Ms. Chen Li-chen; Ms. Liang Shang-yuan and Luo Tzu-kuang, who cared for me after I got out of jail; and Ms. Chou Pi-se who has greatly helped me in the later years of life. They have all been fires in a cold world. As for some other friends whom I intentionally or unintentionally offended or hurt, I am eternally grateful for their forgiveness and acceptance of me.

There's no one I hate, let alone hate most. I've already said that I don't have time to hate. There are only some people I look down on, and some people I think are pathetic, but I'm constantly trying to learn from my friends' acceptance of me and likewise accept these people.

As for my own works that I find most satisfying, I'll only tell you if you promise not to mock my pride. My favorite is An Historical Outline of the Chinese People. Of all the many historical books, only it clearly and concisely describes the 5000 years of Chinese history. Other such books just make you more confused than you were before you read them. My second favorite is Bo Yang's Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government [a translation into modern Chinese of a famous classical work]. This is of course sharing honor belonging to Sima Guang [the original author], but I did make two contributions: (1) I made recondite classical Chinese understandable, and (2) I have given Chinese-or foreigners interested in uncovering the splendor of Chinese history-a chance to gain a complete familiarity by reading just one work. Nothing can substitute for it.

Q: Today's Taiwan finally has true freedom of speech and political democracy, and the political repression that you encountered ought to have been entirely eradicated. Do you think it has been? What are the true crises we are facing today?

A: Today Taiwan truly enjoys a prosperous economy and democratic government. This is a miracle. When 5000 years of traditional Chinese culture absorbed some bits of Western civilization, it gave birth to something completely new here. I believe that it is something glorious for the people of Taiwan, for all Chinese and for Asia as a whole. As far as the economic prosperity is concerned, I haven't made a contribution, but in working hard to push for democracy, I have shed sweat and tears. Nonetheless, political democracy is like a precious silver artifact, which must be carefully polished every day if it is to keep its luster. Otherwise, it will change color or even change shape.

Taiwan's crises

I believe that Taiwan is facing two potential crises: The first is that people at the highest levels of power make poor policies. For instance, internal government documents show that after the Communists unsuccessfully bombarded Kinmen Island 40 years ago, the Communists came to the conclusion that it wouldn't be necessary to go to war again. Mainland officials believed that Taiwan would surely adopt mistaken policies, and that all they needed to do was to wait patiently. The second potential crisis is the heating up of conflicts between various communities within Taiwan [i.e. mainlanders, Taiwanese, Hakka, aborigines, etc.]. I will make a bold prediction: If there is fighting between these groups on the streets of Taipei (say in response to linguistic discrimination), which leads to shots being fired, this will mean that Taiwan is bringing about its own downfall. People are always talking about how the groups are merging together harmoniously, and everyone understands the importance of this, but the truth is that it can't be done. There are some people who will try to stir up these antagonisms to further their own ambitions.

Some things can be predicted, and some things can't. Besides praying that the two sides will have long-term peace, I wish the next generation of Chinese the best of luck.

Photo:

p.126

No so long ago Bo Yang returned to Green Island to plan the building of a memorial for political prisoners who, like him, had been imprisoned there. What was he thinking as he stood in front of the locked iron gates of the Ministry of Defense's Rectification Prison? Could he really recall the events of his past without emotion, as he claimed he could when dictating his memoirs?

p.128

Walking around the prison with Chang Hsiang-hua, his wife and closest companion of his later years, Bo Yang shows that he really is the Chinese proverbial hero who is "able to walk out of the darkness."

p.131

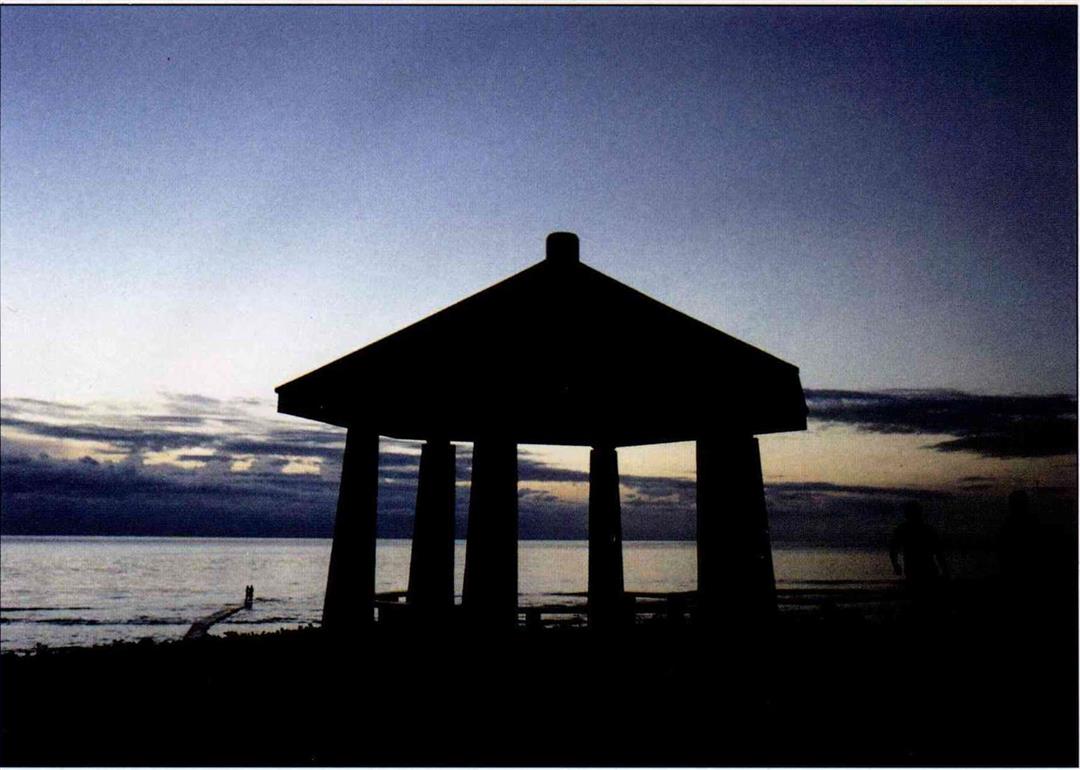

How peaceful Green Island seems in the twilight! Why did it of all places serve for nearly a century as a "gulag" for political prisoners?

How peaceful Green Island seems in the twilight! Why did it of all places serve for nearly a century as a "gulag" for political prisoners?