Rock climbing and mountain climbing are two different worlds in Taiwan. Geology has given the island few sheer rock faces, and those that do exist often have a leisurely slope on the mountain's other side, making an ascent up the steeper face unnecessary. As a result, rock climbers, with their lizard-like, step-by-step climbing techniques, are few in Taiwan, having relatively little contact with mountaineers, in a situation unlike that found in other countries.

What makes people excited at the sight of huge, steep, dead rocks? One expert, noting how monkeys climb around all day, claims it is simply a case of people returning to their primal nature. Walking to the summit itself does not satisfy this breed of person; they need an extraordinary amount of excitement and challenge. Disdaining competition with others, rock climbers prefer to push their bodies and spirit to the limit, with their four limbs shaking by the side of a cliff Rarely do they admit defeat and descend an unconquered mountain. All agree that reaching the top yields an unparalleled sense of exhilaration and accomplishment.

The number of those participating in this "dangerous" activity each year grows in Taiwan, and now there are about 200-300 fanatics, who will go every weekend. Their ages are dropping, with more and more college and high school students taking up the sport.

How dangerous is rock climbing, to be suspended in mid-air by a nylon rope or perched on a cliff with the smallest of footholds, blown about by a stiff wind hundreds of feet up above nothing but rock? N people have been killed in Taiwan rock climbing in over ten years, an accident rate far lower than swimming or conventional mountain climbing. The riskiness of the sport demands extra care and precaution, which insures that accidents will be kept to a minimum. Commenting on a mountain climbing disaster this summer, when a college student lost her life, a rock climbing expert says that if the group used safety rope techniques standard to all rock climbing ascents, the tragedy need never have happened.

Precautions and prudence aside, it still looks dangerous, which has held back its growth in Taiwan. In Hong Kong, some employers send their employees for rock climbing training, and those that pass the test find their promotion opportunities greater than those that fail.

A shortage of suitable rock faces has also created problems. Most spots are located in the northern part of the island, within easy reach of Taipei. Among the favorites are Tap'ao Cliff, known as both the "beginning course" and the "graduate school" for rock climbers, with a broad range of ledges suitable for novices and experts alike Dragon Cave, the "university," with its coarse, clean rock and multitude of levels, also has many visitors, some of whom drive hours from south Taiwan to test their skills.

Rock climbing is a sport of hands and feet. Instructors teach pupils to move only one limb at once, keeping the other three fixed on the side of the rock. The advance person protects those beneath, affixing the rope to a spot in the cliff and waiting for the others, the rope tied round their waists, to climb up, step by step. Then the advance person must ascend, without the benefit of such protection.

Before climbers ever see a mountain, they undergo a training program. Such a course will teach them how to conserve their strength and a variety of climbing techniques. One method, called "Chimney Climbing," involves putting one's back and feet on opposite walls and then using the limbs and back muscles to inch upward. When faced with a protruding, slanting formation, climbers will straddle the edge, as in riding a horse, earning this technique the name, "Jockey Climbing." Everyone can learn these techniques, but what makes a good climber is his or her ability to find footholds and handholds. Long arms and legs, of course, never hurt.

Among the attributes necessary to make a good climber, speed ranks very low, but courage is quite important. Many beginners, fearful of falling, put their whole body on the cliff, which only increases their chances of a slip. Instructors tell students to use their feet for support and their hands for balance, but finding a sense of balance suspended in mid-air is difficult for many.

Suppleness and good cardiovascular condition are also important. Climbers need agility to latch onto hard-to-get-to places and use their muscles in ways they rarely do in everyday life. A strong heart and pair of lungs prevent climbers from tiring easily. Experts frequently do limbering exercises, lift weights and jog to maintain their physical condition.

Sometimes strength and nimbleness are not enough, however, and climbers must use nails and picks. True moutaineers will take them out of their bags only as a last resort. Besides being a waste of energy, climbers dislike the marks and scars they leave on the cliffs' surface, preferring "clean climbing." Nevertheless, most parties bring along a set of pins just in case.

Equipment includes helmet, rope, harness, pitons, slings, hammer, chocks, carabiners, and boots. Total expenses amount to NT$20-30,000 (US$500-750), but ten years ago, costs were considerably higher, due to the lack of production facilities and market in Taiwan. Proper standard nylon rope was unavailable, leaving climbers to settle for hemp. Now the situation has improved considerably, with supplies being adequate if not plentiful.

The rope is every climber's lifeline. Most kinds, whether nylon or hemp, are simply not up to the job, which requires that they stand 2000 kilograms of stress. One missed stitch disqualifies a rope, since it may mean a life on the mountain. One standard nylon rope costs about NT$4000 (US$100), and most climbers would sooner lend their toothbrush than their rope, such is the emotional tie formed between experts and this vital piece of equipment.

Assembling a climbing team receives the same dead seriousness. From one angle, this sport could be viewed as a small group of people who take turns in placing their lives in each other's hands. Close rapport is essential. Climbers are often separated by long distances, unable to see or hear their partners due to rock and wind, dependent only on the tug and tension of the rope for information on whether to stay or advance. One team which climbed the east face of Yushan in 1981 added a new climber at the last moment, which resulted in another climber being exposed unnecessarily to fierce winds for an hour and a half because he misread the message sent via rope by the new climber.

With opportunities limited by the terrain, many people hope to go overseas to improve their skills, but the costs and time involved rule out this option for all but a few. Some urge foreign climbers be invited to Taiwan, feeling that their skills and objectivity in judging sites will benefit the sport here, but cost remains a formidable obstacle.

Rock climbing is not for dilettantes. Climbers must practice and exercise often. Perhaps students are best suited for the sport. Most men, after college graduation and military service, find jobs and start families, and lack the freedom which allowed them to spend hours on a rock. One climber says he regularly hammers two more pitons for added security every time he thinks of his wife and children. Perhaps he can help satisfy his climbing urge by passing on his expertise to the younger generation, for as long as there are massive, sheer cliffs, there will be rock climbers.

(Translated by Mark Halperin)

[Picture Caption]

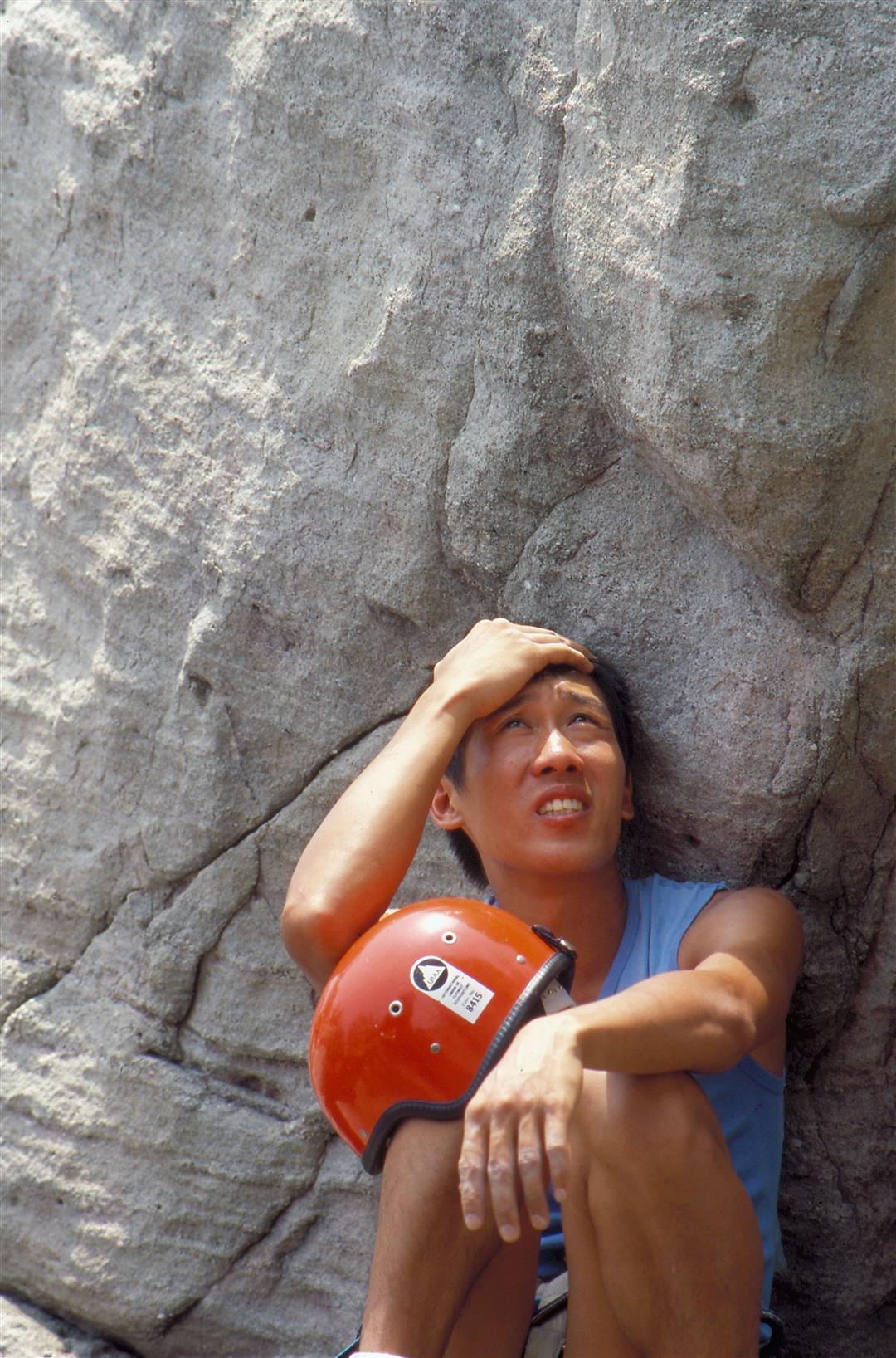

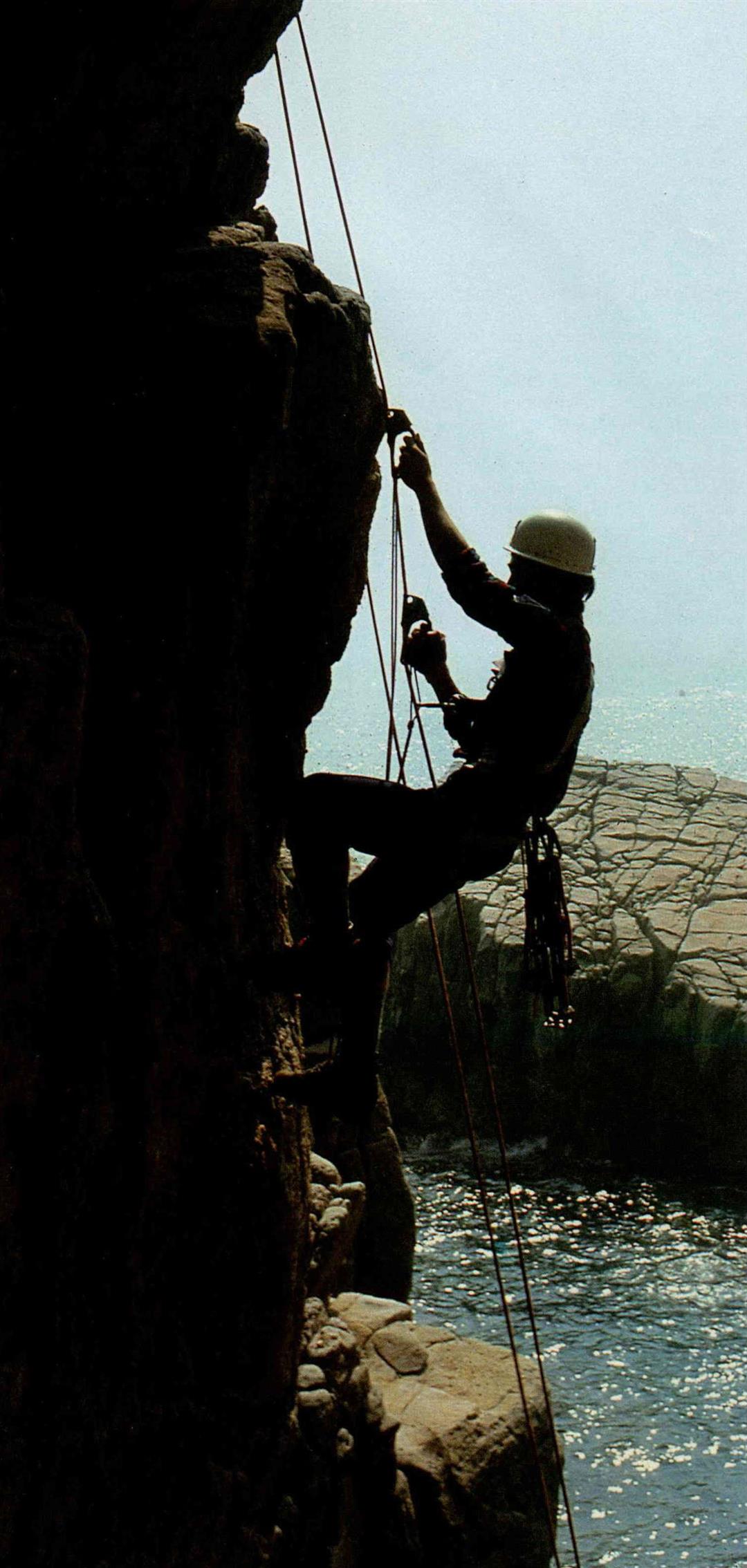

On the face of it at Dragon Cave Rock climbing requires unusual courage and agility.

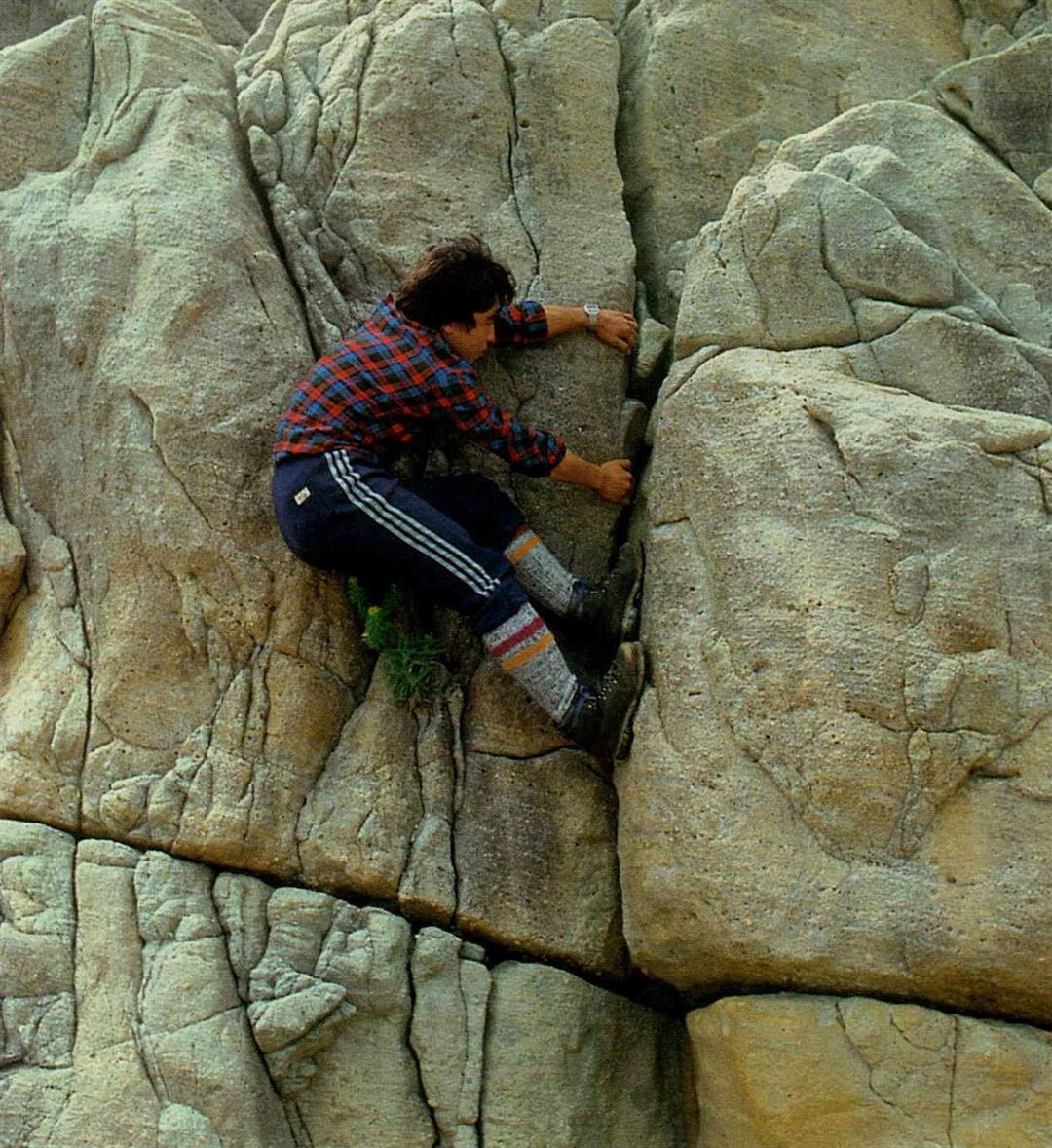

Climbing without rope, this expert braces his feet against the rock while inching upward with his hands, one of the most difficult maneuvers in the sport.

Rock climbing even makes spectators tense.

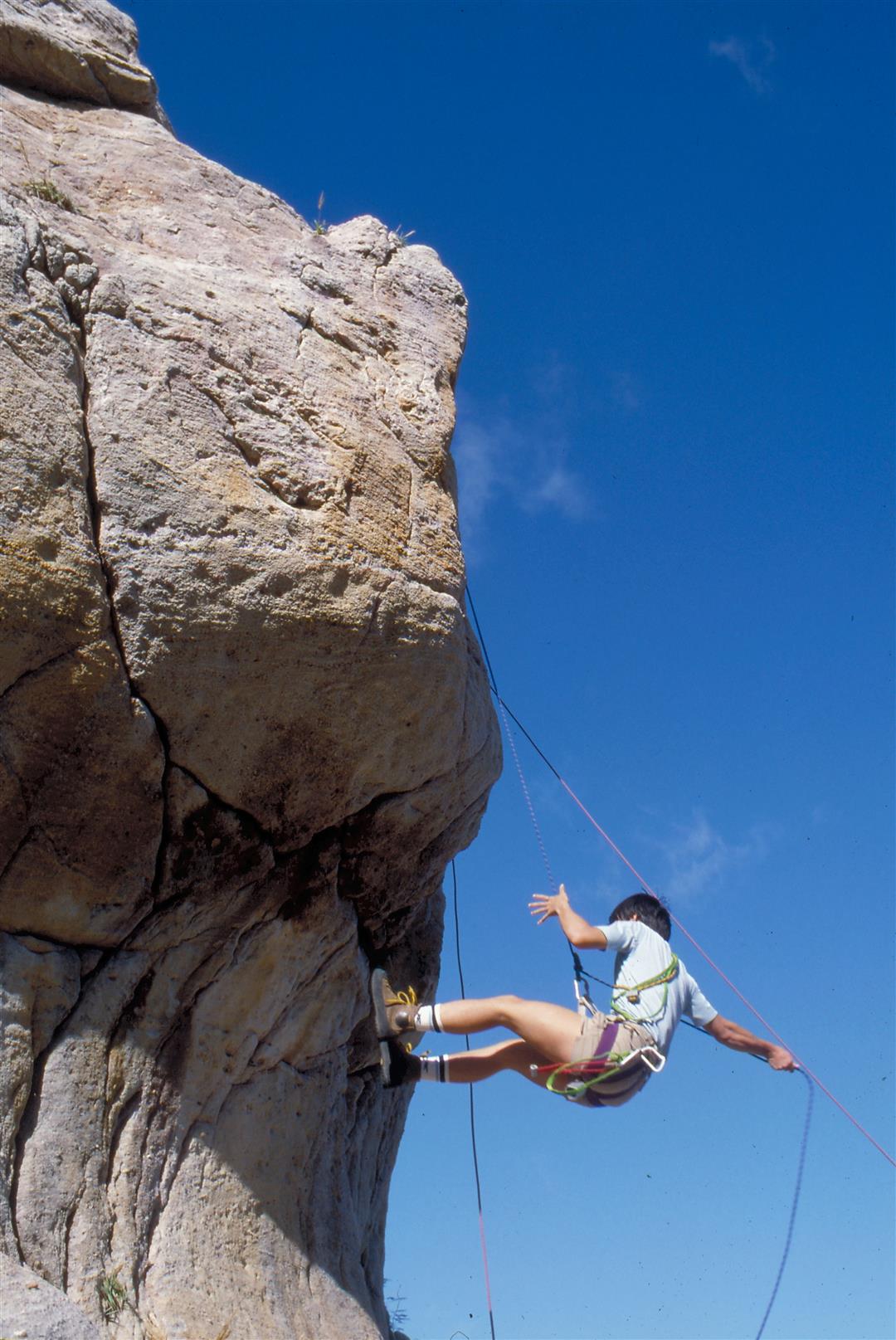

Using the right hand to steady his descent, this climber proceeds at a slow, rope-climbing pace.

This dangerous cliff at Dragon Cave is one of the most difficult courses at "the university."

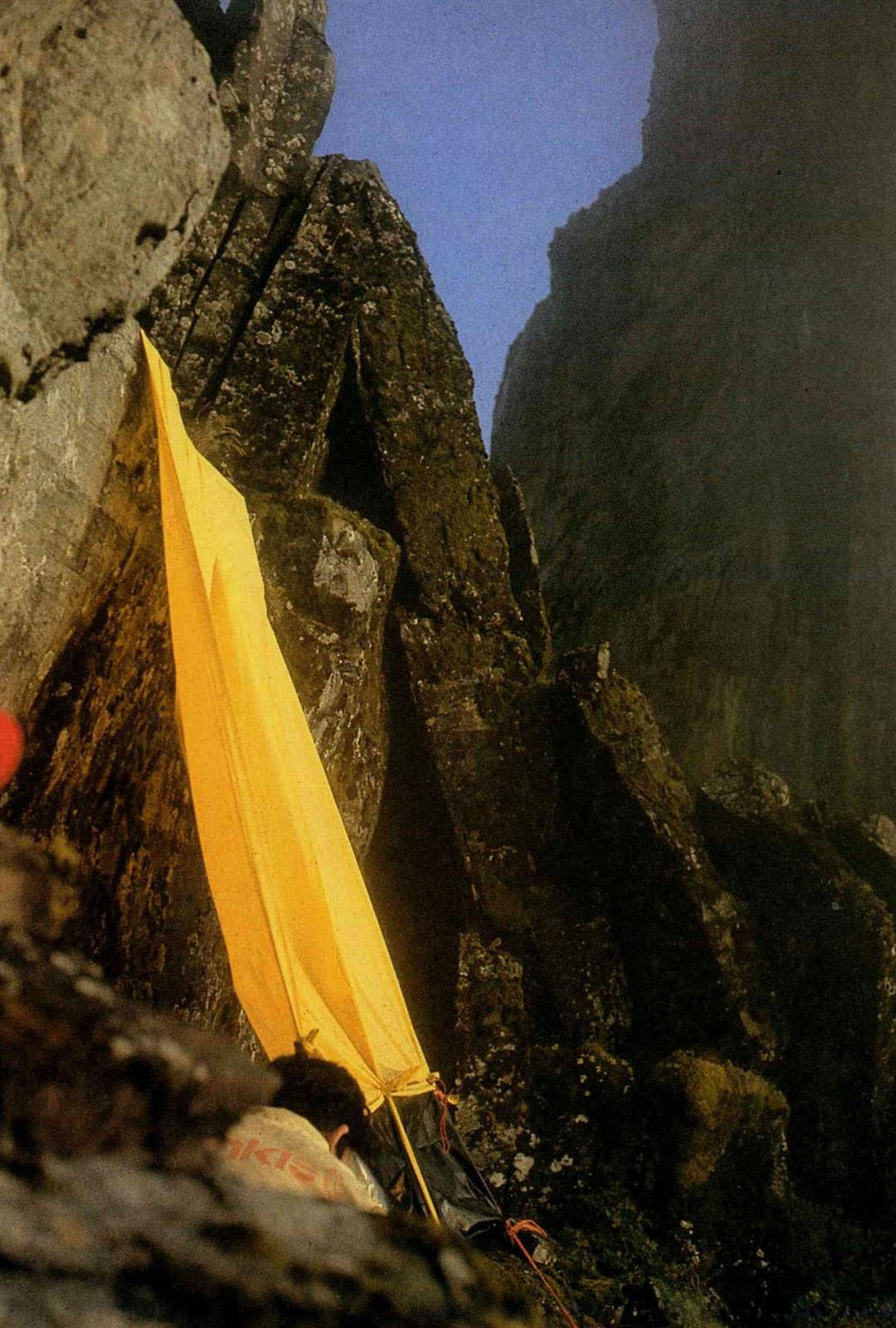

Climbers prepare to spend the night on the north face of Tapa mountain.

This chock wedged tight may save a life.

A climber adjusts his safety harness and prepares to climb.

Having already reached the top, climbers pass the chock.

The jumar is an indispensable tool. Climbers to the rear use it to steady their ascent up the rock.

Rock climbing even makes spectators tense.

Climbing without rope, this expert braces his feet against the rock while inching upward with his hands, one of the most difficult maneuvers in the sport.

Using the right hand to steady his descent, this climber proceeds at a slow, rope-climbing pace.

This dangerous cliff at Dragon Cave is one of the most difficult courses at "the university.".

Climbers prepare to spend the night on the north face of Tapa mountain.

This chock wedged tight may save a life.

A climber adjusts his safety harness and prepares to climb.

Having already reached the top, climbers pass the chock.

The jumar is an indispensable tool. Climbers to the rear use it to steady their ascent up the rock.