One April day about ten years ago, I took my children with me on a long trip to Saudi Arabia to be reunited with my husband, who was living abroad. Back then my oldest child was in the third grade and her younger brother was in kindergarten. In moving the children so far from home, the question of how they would study Chinese is what worried me most.

We discovered that there weren't many Chinese in Riyadh and no regular Chinese school. Hence, we immediately went to register the children at the American school, so they could go somewhere for full-day classes. Much to our surprise, we were told the older child would have to take an entrance exam (which wouldn't be required of her younger brother because he was entering in first grade). At the time our girl's knowledge of English didn't go beyond her ABCs, so we promptly began force-feeding her the various bean sprout-like shapes of English letters and words. There were about two months between the time we registered and the exam, and every day at 8:00 in the morning we blew the bugle call for intensive English training. We went over the Children's English book I had brought from Taiwan page by page. We crammed into her the words for colors, directions, commonplace objects, animals, fruits and vegetables. To make a deeper impression, I also made some simple drawings to use as teaching aids. If in the course of our daily lives we came across something we had studied in English, we would tirelessly review its pronunciation and spelling. When we were eating, we'd go over again the English for the fish, vegetables and fruits on the table, as well as for knife, fork, chopsticks, bowl, plate, and so forth.

During the course of these two months, I knew that she wasn't really digesting all we were putting on her plate, but for the sake of getting her into the school, we figured it was best that she just chewed on whatever we gave her, however bitter the taste. And in the end she passed the test. From this experience I learned that children are very malleable, and that whatever adults stuff into them, and however bored they may be by it all, they will absorb some of it. Similarly, when I was in elementary school, the teachers would have us prepare for an exam by constantly repeating our lessons. Without needing to do much studying at home, academic advancement went smoothly. Once I came to this understanding, I said to my daughter, "Child, so that you won't fall behind in your Chinese studies and won't regret not going to elementary school in Taiwan, I want-without putting any pressure on you-to read Chinese with you, so that the language will be with you as you grow up."

Parent-teacher coordination

Chinese living abroad want to pass along Chinese culture to future generations, and certainly don't want their children and grandchildren to forget their roots just because they grow up overseas. Fortunately, in Saudi Arabia there was, and still is, a Chinese school for the children of the staff of the ROC representative office. Although it opens for only a half day every Thursday morning, it does allow the Chinese children living here to continue their education in the mother tongue, which greatly helps to pass along the language to the younger generation. But frankly speaking, holding class in Chinese only once a week for four hours is not enough, so parents must do a lot of coaxing and supervising of study at home. In other words, the study of Chinese when abroad ought not to be confined to a certain place and time. Most importantly, parents should take the initiative. Start at home and then coordinate your efforts with those of teachers in the Chinese schools. This approach will bring the best results.

First, parents ought to establish rules that encourage learning Chinese at home, by prohibiting children from speaking other languages there. Take our family. After my older two children began attending a foreign school, they became naturally quite fluent in English, and it was hard for English not to slip from their tongues when they came home. At such times, I would urge them to converse in Chinese, adopting the slogan "English in school, Chinese at home." We have insisted that even our third child, who was born in Saudi Arabia and is ten years younger than his sister and seven years younger than his brother, speak Chinese at home-even though English has predominated among our neighbors and on our television set. We can happily report that the Chinese of our nine-year-old is at third-grade level, despite living abroad for so long. He may only attend Chinese classes for a half day every week, but he lives in a home that is an extension of his Chinese school.

Films and books

Besides demanding that Chinese be used at home, I frequently take it on myself to visit the ROC representative office here to select tapes of Taiwan television dramas or Chinese movies for the kids to enjoy on the weekends or vacations. Both the shows and the commercials provide good material for studying Chinese. And the kids watch happily, especially the dramas, from which they won't be pulled until they've watched clear to the end of a series. Our air-mail subscription to a Taiwanese newspaper also provides a valuable source of study material. As soon as the newspaper arrives the whole family gathers around to read it. The adults read the news, the older children the kungfu fiction serials, and the youngest mainly looks at the "Children's World" section. The paper truly serves as spiritual sustenance for the whole family.

What's more, my children's elementary school library has a variety of books supplied by the Overseas Chinese Affairs Commission, which are suitable for children of varying ages, from those just entering school, all the way up to sixth graders. Everything they should have, they've got. The library has open stacks, and you can freely borrow their books. Parents ought to encourage their children to take out books from Chinese libraries and then read them together. With such exposure, day after day, month after month, their Chinese is sure to improve. Meanwhile, they will be fostering a habit of reading books in Chinese.

Show concern for Chinese homework

Every week, when the children come home from Chinese class, parents ought to ask such questions as "What did your teacher teach you today?" "Do you have any homework?" or "How did you do on the test?" In response to my interest and concern, they tell me about what happened in class. If they do well on a test, I give them a little spending money as a prize.

Every week without fail, there is homework that entails studying new characters and new vocabulary, copying characters over in a notebook, practicing dialogues, copying passages from the textbook, and so forth. To avoid boredom, instead of having the children do one kind of assignment a day, it's better that they do a bit of each kind at an appointed hour every day. They shouldn't do too much on any given day, but they should by all means preserve the habit of writing at least some Chinese every day. On no account should they do a lot on one day and then go for many without writing anything at all. Children are likely to have forgotten all their lessons by the time they open up their notebooks several days later and feel frustrated as a result. Knowledge accumulates a bit at a time, and the same logic applies to learning Chinese. By all means, avoid "feast for a day and famine for ten."

A set time for reading together

To prevent things from getting all mixed up, it's best to keep separate times for children to do English and Chinese homework. Talk with your kids about how they can make their own homework schedule. Ideally, parents should think of their children's Chinese homework as their own, and go over it with them. This both stimulates interest and provides a way to get closer to your children. Parents should try their best to do their own reading and writing at the time their children do theirs, or else they should sit by their children, knitting or sewing. The sight of the whole family gathered around the lamp, each doing their own tasks-what a vision of family bliss!

The period when children most need to read with their parents is from when they first enter elementary school until the fifth or six grade. During these five or six years of tremendous physical and mental growth, parents who are truly concerned about their children's development ought to spend as much time as they can with them, instilling in them a sense of Chinese culture while teaching them to use Chinese. After this period is successfully navigated, there will be no need to be anxious about your children's Chinese.

The best time to read with your children is right before they go to bed. Read from a book of children's stories, or teach them some children's songs, or play some Chinese tapes from which they will learn without even realizing it. Over time their Chinese is sure to improve. If circumstances permit, during summer and winter vacation bring the children back to Taiwan so they can come in contact with your relatives and friends or take summer classes. While these may last only a month or two, the rewards will be great.

Give children turns as teacher

So the children can practice writing, I bought a large, instructional-use white-board at a stationery store. Every week after Chinese class, I am in the habit of talking to my son about his lessons to see if there was anything he didn't understand. He shows an indescribable sort of glee when using the whiteboard. Sometimes, in an impulsive moment, I pretend not to understand an everyday expression or something in the textbook, and ask him to be the teacher and explain it to me. I sit at the table in front of the whiteboard and play the well-behaved student, while he writes out the correct character. Using a discarded radio antenna as a fescue, he taps on the board and says, "Attention! Look! Look here! The character is written this way. . . ." Sometimes he asks me questions, and I act as if I don't understand. The more he speaks, the more energetic he gets, and sometimes he scolds me with a schoolmarmish tone. He really gives the appearance of a little teacher, and sometimes even takes the initiative to say, "Mama, let's have class, OK?" At such times, nothing should be given greater importance than teaching. At home, keep a whiteboard-it makes no difference whether it is large or small. When you're not using it for class, it can serve as a message and reminder board. It is also a good place for children to draw.

Shoots need watering

Studying Chinese overseas is not easy. Parents and teachers need to coordinate efforts to cultivate children's language talents, like gardeners caring for tender new shoots. We need to show love, attention and patience-assiduously weeding and watering. It takes great effort to pass along Chinese culture so that our children and grandchildren, descendants of the Yellow Emperor, can display true Chinese character. But when your sons and daughters speak Chinese fluently and have a broad knowledge of the essence of Chinese culture, understanding what it means to be an upstanding Chinese, you are sure to treasure your memories of the process and think the results were well worth the effort.

p.53

My son, the little teacher, in front of the whiteboard.

p.54

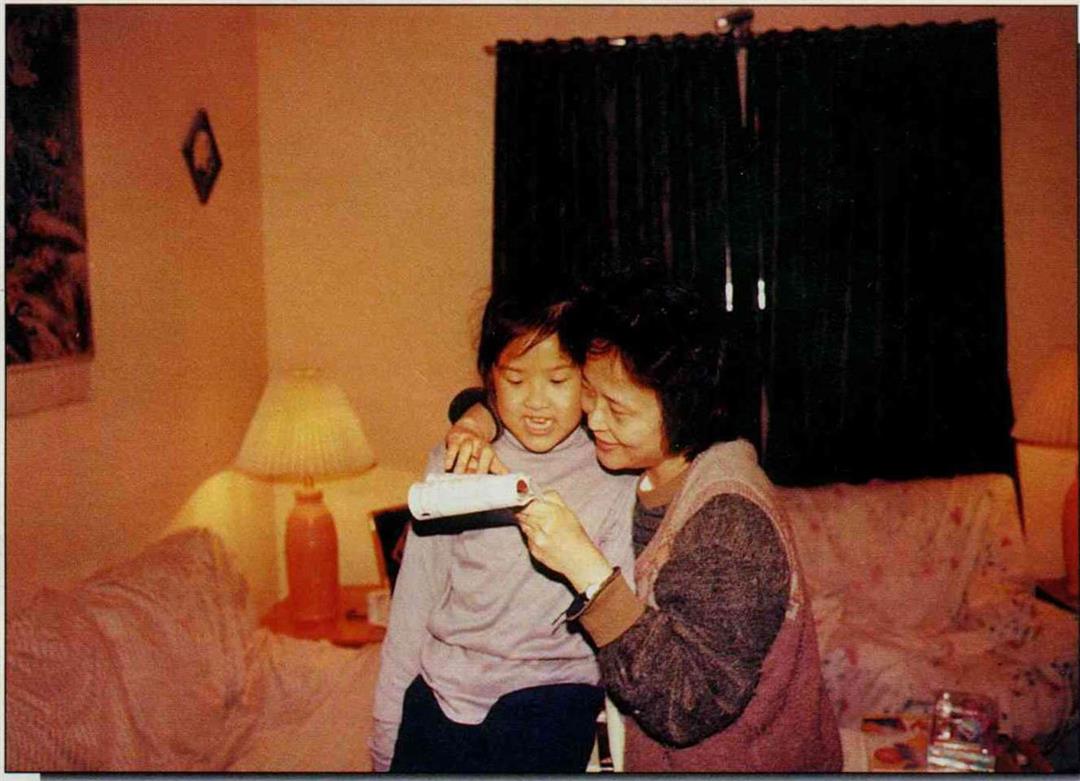

Don't forget to teach your children Chinese when playing games.

Don't forget to teach your children Chinese when playing games.