Literary seas

Chang had no idea he could write, but was well aware that he had no future in soldiering. Knowing that feigning illness wouldn't free him of his enlistment and that he had nowhere to desert to, he began studying on his own, working character by character through stories in discarded newspapers he picked up. Military life was filled with slogans and posters, so he practiced reading these as well. He went over them again and again, making a game of rearranging the characters and phrases they used, then reassembling them into a poem he scribbled in a notebook.

When a squad leader responsible for "ideological inspections" read it, he told Chang, "You could submit this for publication." Chang was just a foot soldier and had no idea how to submit something to a publisher, so he let the squad leader handle everything. Soon thereafter, his poem appeared in the "War Stories" section of the Taiwan Xinsheng newspaper. The NT$15 the paper paid for submissions was a good deal more than his NT$12-per-month salary!

Chang had originally planned to use the money to buy the cheapest of the then-fashionable Wearever brand fountain pens, but it ended up being confiscated by the army. His monetary setback aside, Chang had at last come to appreciate the saying that "the quest for knowledge is a thirst."

He bought complete editions of the Tang and Song-dynasty poems on a payment plan to improve his writing skills, and also began devouring "linked chapter" novels. The books introduced him to so many unfamiliar words that he was obliged to read with a dictionary by his side. He then persuaded a friend to pay NT$18 to register for a course with the Chinese Literary Arts Correspondence School. "My friend paid for it, but I studied the materials and did the work," recalls Chang. He was at last swimming in the vast seas of literature.

Chang piled up poems during his time in the military and in 1962 published a collection entitled A May Hunt. He also placed second in the short poetry category in the very first Armed Forces Golden Statues Awards for Literature and Arts contest, and had poems included in Collected Poetry of the 1970s (Ta-yeh Booksellers) and A Collection of Contemporary Chinese Poetry, published by the Epoch Poetry Club.

When Cheng Chou-yu read Chang's poems, he commented on Chang's adroitness at creating images and putting words together. Chang, on the other hand, felt that while reading poetry was his greatest pleasure in life, he himself had no talent for writing it. Being honored as a "poet" left a bitter taste in his mouth.

"In those days," he recalls, "you had Luo Fu, Ya Xian, Xiang Ming and me. We got started together and were at about the same level, but when we hit a certain point, they kept moving onwards, while I just marched in place."

Though Chang himself stopped writing poetry without a second thought, Luo Fu turned Chang's uncertainty about whether his childhood betrothed had lived or died into the famous "Mailing Shoes":

Separated by 1,000 rugged miles / I mail you a pair of cloth shoes. / A single / letter without words / containing 40 years of conversation. / Things I want say to but cannot / simply sewn / sentence by sentence / into the soles.

I've kept this conversation inside for so long / a few phrases beside the well / a few in the kitchen / a few under the pillow / a few in the flickering light of the midnight lamp....

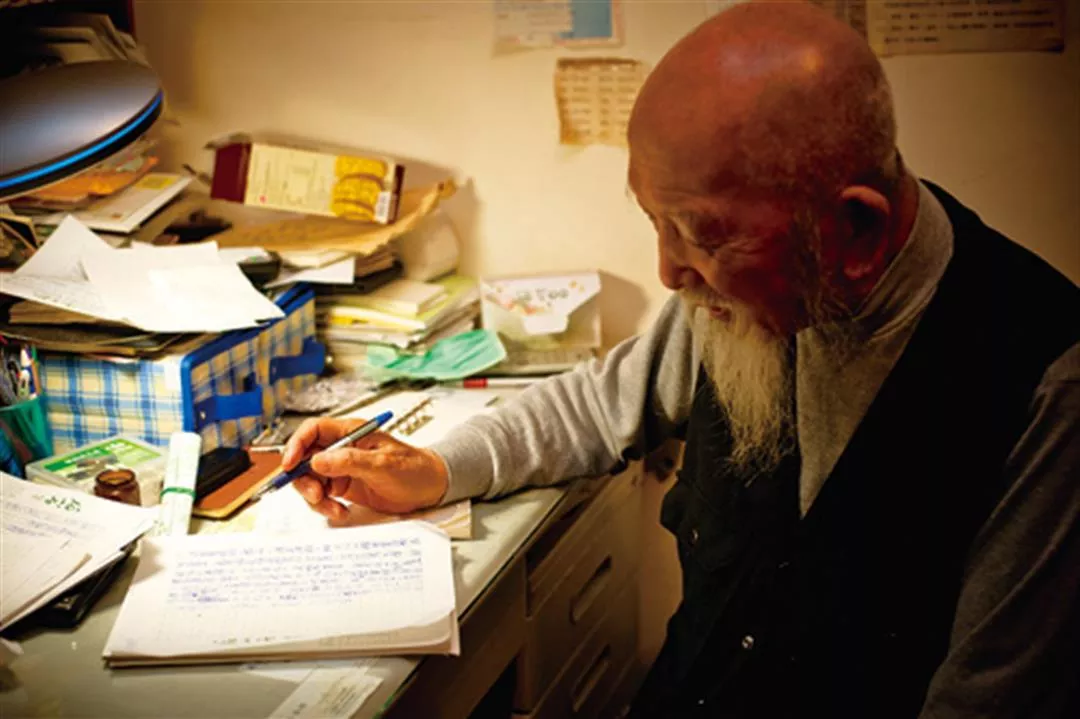

Chang doesn't get computers, and instead writes his stories stroke by stroke on sheets of manuscript paper. Chang's lady friend "Fan" then posts the stories online, where they are creating a stir among young people.