A Tale of Strong Presidents with Weak Constitutions

Laura Li / photos courtesy of Historical Commission, Central Committee of the KMT / tr. by John Murphy

March 2000

The countdown to the millennial elec-tion has begun. When the results are revealed on March 18, no matter who stands at center stage, he will have to face critical problems of constitutional reform and of inter-party coordination. Looking back at the history of the Republic of China, new presidents have often faced problems of constitutional change and relations with the parliament. But, fortunately, we can see that the century-long road to democracy has not been walked in vain.

When New Party nominee Li Ao, who is well versed in modern Chinese history, registered as a candidate for the "Tenth Term of the Presidency of the ROC," he noted that these ten terms only cover the period since the formal adoption of the ROC constitution in 1947, while in fact Republican-era presidents had been chosen by set procedure even before that, and he reminded everyone not to ignore them. But if you went back to the first year of the Republic, 1912, when Sun Yat-sen was named first provisional president, and tried to count the number of presidents, you might have a hard time figuring out just how many presidents the ROC has had. Even an historian might find it a tough assignment.

Constitutional confusion

Just as the number of presidents is hard to figure, so is it difficult to pin down just how many constitutions there have been, and of what type. Since the passage of the first provisional constitution in 1912, the ROC constitution has had a turbulent history, and even today the pains of constitutional transition are still being felt. There have long been triangular wrestling matches putting the parliament, the president, and the constitution in the ring together. Because the vote is likely to be split three ways, whoever wins the March 18 presidential election will have to forge coalitions and mediate among the different parties, and there are fears of more constitutional turbulence ahead.

Fortunately, there are a few things we can be confident about: Though today's constitutional environment is confused and rapidly changing, no one will be assassinated, the parliament will not be forced to dissolve, there will be no division of the national territory, and there will be no bloody wars. Chinese have, after all, been through all that before.

Let's go back to the early years of the Republic. In 1912, Sun Yat-sen was elected first provisional president. In hopes of encouraging the "last emperor" of the Qing dynasty, Pu Yi, to peacefully abdicate, Sun struck a deal with Yuan Shikai, a Qing military leader, that Sun would give up his position to Yuan if Yuan forced Pu Yi to step down.

But the constitution-makers of the time did not trust the ambitious Yuan. They therefore abandoned the outline plan for the new government, which had originally envisaged a presidential system, and adopted a new provisional constitution which would establish a cabinet system. Under such a system, the premier would act as a counterweight against Yuan. Not surprisingly, this system led to constant power struggles between President Yuan and successive premiers. Even Tang Shao-yi, an old friend of Yuan's who was the first premier under the system, resigned in anger after Yuan issued executive orders without respecting the cabinet's power of approval.

In 1913, the Kuomintang won an overwhelming majority in the parliamentary elections. KMT leader Song Jiaoren had always strongly favored a cabinet system. If a true cabinet system had been established, there would certainly have been bitter power struggles between Song, whose KMT commanded a parliamentary majority, and Yuan, who did not have any party organization. Unwilling to either withdraw or cooperate, Yuan simply hired killers who assassinated Song in the Shanghai train station.

Song thus became the first person in ROC history to be sacrificed over the constitution. There was no doubt about Yuan's complicity-telegrams from Yuan arranging the murder were found in the assassin's home-and public opinion was outraged. But those were the days when political power grew out of the barrel of a gun, so what could the courts do to Yuan Shikai? Yuan then coerced the parliament into awarding him the presidency, after which he promptly declared the KMT to be a rebellious organization, and "revoked" the powers of office of more than 400 KMT members of parliament. The parliament was left with too few members to even reach a quorum, and was forced to dissolve.

Means or end?

Why was Yuan so anxious to dissolve the parliament? Chang Yu-fa, an expert on modern Chinese history at the Institute of Modern History of the Academia Sinica, says that in the early Republican era, there were still many idealists in the parliament, and they would not bow to Yuan's threats nor succumb to his bribes. They were determined to produce a draft constitution that would create a cabinet system and a division of powers between central and local government. This was precisely the opposite of Yuan's ambition to create a highly centralized presidential system. When Yuan sent people to the parliament to lobby on behalf of his preferences, they were driven away in anger by the members. You can imagine how furious and desperate Yuan must have been.

Yuan's greatest injury to the young republic was in making the nation's basic law a tool in his power ambitions. After the dissolution of the parliament, Yuan then convened an extra-legal convention to draw up a new provisional constitution. This created a "super-presidential system" in which the president could declare war, make peace, and establish the official civil service system and its rules without requiring approval from the assembly. The president could also issue emergency decrees and enjoyed emergency financial powers. Later Yuan amended the presidential election law so that the president could serve an unlimited number of terms, and could choose his own successor-even his own son-without restriction or outside approval. There was virtually no difference between such a president and an emperor.

"In the early Republican era, on the surface all the political figures were talking about creating a constitutional system or drafting a basic law, but what they really meant was 'rule by law' (using the law as a tool to control others, with the option of altering the law to meet the needs of the elites) rather than true 'rule of law' (in which the law would stand above the rulers, and could not be easily altered)," says Ger Yung-kuang, a professor in the Graduate Institute of the Three Principles of the People at National Taiwan University.

Chang Yu-fa, on the other hand, notes that, however much the advocates of constitutional democracy wanted to get on with the work of establishing the nation's basic law as quickly as possible, it was necessary to take into account the political realities of the time. Under the circumstances, it is no surprise that the civilians of the constituent assemblies, divided as they were among many parties, had to concede to the demands of a series of warlords-Yuan Shikai, Feng Guozhang, Cao Kun-and elect these warlords or their puppets as president. They could only hope that one of these military leaders would respect the power of the parliament to create an enduring basic law for the country. But Yuan's dismissal of the parliament delivered a harsh blow to parliamentary and party politics, causing severe damage to the budding young democracy.

The presidency up for bid

Ultimately, Yuan attempted to restore the imperial system with himself as emperor, but died soon therefter. His successor Li Yuanhong lacked real power, and the political situation deteriorated into increasing anarchy. In 1917, Duan Qirui replaced the parliament with an assembly of his own followers.

Some of the members of the original parliament then responded to the call by Sun Yat-sen to go to Guangzhou and set up a provisional assembly. But, despite Sun's dedication to rule of law, circumstances were against him. In Guangzhou, the ideal of constitutional politics was never realized. The government system there changed frequently and proved to be no more stable or capable than the northern regime.

Thus, in the early ROC, the constitution was mainly a tool to legitimate the aggrandizement of power by those with the force to back themselves up. Meanwhile, elected assembly members, who should have stood for the rule of law, were bought by various parties, culminating in the purchasing of the presidency by warlord Cao Kun.

In 1922, war broke out between Hebei warlords led by Cao Kun, and the forces of Manchurian warlord Zhang Zuolin. After winning victory, Cao-under the pretense of "restoring the legitimate system of government"-forced then-president Xu Shichang from office, reconvened the old parliament, and invited former president Li Yuanhong back in to office. But less than a year later, Cao Kun, who was anxious to make himself president, employed criminal gangs to force Li to resign and flee for his life. With the presidency in sight, Cao then embarked on bribery of the assembly members.

At this time Sun Yat-sen formed a three way alliance with the Manchurian and Hubei warlord armies to organize an attempt to bribe parliamentarians not to vote in Yuan's charade of an election. The alliance declared that any assembly member willing to leave Beijing could go to Tianjin and collect 500 yuan in silver in travel expenses to go south; if they went to Shanghai, they could collect another 300 yuan. Faced with offers of money from both sides, assembly members passed each other heading in one direction or the other as they waffled between denouncing Cao as having unlawfully unseated Li Yuanhong and supporting Cao as president. Most adopted a wait and see attitude, and bent with the wind.

The decisive factor in this battle between "bribes to vote" and "bribes not to vote" was-need we say it-the highest bid. In the end Cao offered 5000 yuan in silver for each vote, far more than the 3000 offered by the alliance. Chiang Yung-chang, a professor of history at National Chengchih University, says with a sigh that back then you could get more than 100 catties of rice for less than 10 yuan. 5000 yuan was enough to purchase a small Western-style house, and was equivalent to two years' salary for a professor. Facing an uncertain fate, and caught between the northern and southern governments, parliamentarians were unable to hold meaningful sessions, nor could they collect any regular salaries, so it is no surprise that these early parliamentarians, many idealistic to start with, ended up giving in to temptation. There is nothing new under the sun about intellectuals being sullied by the realities of hard-nosed politics.

Chang Yu-fa points to an irony of history: In 1923, as the whole country was lambasting Cao Kun, in fact the parliament was finally able to pass the first formal written constitution in the nation's history; this is known to history as the Cao Kun constitution. This document incorporated the spirit of the cabinet system and the division of powers between center and regions, and in many ways conformed to the aspirations of Sun Yat-sen. But by then the pressure on Cao to step down was enormous; warlords were attacking each other verbally, and it appeared civil war was imminent. Who had time to think about the constitution? In the end, there was not even an opportunity to promulgate and put into effect this basic law which had taken so much time and effort just to write.

A three-stage process

After Cao Kun, people in China lost trust in words like "democracy," "parliament," and "constitution." The situation deteriorated into anarchy and civil war. Many intellectuals concluded that another revolution was necessary to save China. By that time, Sun Yat-sen had already established the Whampoa military academy and begun building the National Revolutionary Army. This period also witnessed the rise of radical communist thinking.

In 1931, the Nationalist army, led by Chiang Kai-shek, completed the Northern Expedition and reunified the country. This completed the stage of "revolutionary government" and marked the beginning of the stage of "tutelary government." In this period, which was supposed to prepare the country for future constitutional government, the KMT was in full control, and such terms as parliament, elections, and political parties disappeared from view. But Chiang, in his own way, never forgot the project of constitutional government. In 1931, the Nationalist government invited selected representatives of rural society, labor, business, and the education sector to convene to draw up a provisional constitution for the tutelary period. Later the legislature drew up a draft constitution, and eventually, in 1936, the "May 5 draft constitution" was made public.

Unfortunately, shortly thereafter Japan began its war on China, and the constitutional project was put on hold. It was only in 1946, after the war, that the government was able to convene the the First National Assembly, which was charged with writing and passing the constitution. Working from the blueprint of the May 5 draft, the Assembly adopted the Constitution of the ROC, finally completing this historic mission.

There are many interesting anecdotes surrounding the adoption of the constitution. Chang Yu-fa reveals that Generalissimo Chiang, like other power-holders before him, favored a strong presidential system and opposed a cabinet system (which would have been more balanced). He once sharply remarked to the delegates, "I am not Yuan Shikai, why do you want to restrict my powers?" Chiang also had a plan to "defer" to the scholar Hu Shi and leave the presidency to Hu, while Chiang himself would hold real power as the premier. This idea came to naught because of opposition to Hu-who was not in the KMT-from KMT heavyweights.

If not for the civil war pitting the KMT against the Communist Party, would constitutional government have really effectively come into operation after the formal promulgation of the constitution on December 25, 1947? No one can say for sure. In any case, the Nationalist government quickly collapsed and the remnants retreated to Taiwan. Fearful that the Communists would also swallow up Taiwan, Chiang essentially suspended the constitution and began to rule based on the so-called "Temporary Provisions" to that document. The government suspended all rights to free assembly, including the right to form political parties or civic associations. The era of constitutional government turned out to look not much different from the era of "tutelary government," and the "emergency" provisions remained in effect for 40 years.

Where to next?

Chu Yun-han, a professor of political science at National Taiwan University, says regretfully that the "Regulations for the Period of Mobilization for the Suppression of the [Communist] Rebellion" were a severe blow to the spirit of constitutionalism, which had only resurfaced after many setbacks. The provisions concentrated power in the hands of the president and eliminated real elections; Chiang Kai-shek would eventually serve five terms before dying in 1975, still in office, at the age of 87.

There was some return to the spirit of cabinet government under Chiang's successor Yen Chia-kan because the real strongman, Chiang Kai-shek's son Chiang Ching-kuo (who succeeded his father as KMT party chairman), wanted to observe the form of a constitutional succession and therefore ruled the country from the post of premier, while Yen served as a figurehead. But in 1978 Chiang Ching-kuo assumed the presidency, and it naturally became once again the center of power. Meanwhile, the National Assembly members elected in China in 1946, who were said to represent the legitimacy of the ROC, were exempt from having to face new elections in Taiwan, and over time an ever-growing gap emerged between these aged mainland-elected elders and Taiwan's rapidly changing society.

In his last years in power, Chiang Ching-kuo lifted martial law and began the return to constitutional government. But how could a constitution drafted in 1947 for the 35 provinces of China be suited to little Taiwan? In the last nine years, consequently, there have been five sessions of constitutional revisions to adapt the basic law to Taiwan's situation. In this process there has been so much incessant wrangling that people are inured to it, and hardly even consider this process strange at all.

Chu Tsao-hsiang, a National Assembly member from the New Party and a professor at Chinese Culture University, says: "When I was a student, I remember our constitution class teacher saying, 'forget that article,' 'skip that provision.'" Now that Chu himself is teaching a course on the constitution, he faces a different problem: "I often have to remind students that the constitution gets amended virtually every year, so they should be careful not to buy an outdated version!"

A constitution is meant to be the nation's basic law, so naturally it is not a positive sign if it is frequently amended. Yet, compared to the sense of irrelevance that teachers had about the constitution in the old days, the fact that Chu can, as an elected member of the opposition, stand up in the National Assembly and call for a boycott or can, as a scholar, be a "dog barking at the passing train" without having to worry about being "crushed under the wheels," definitely marks progress. The constitutional environment over the past hundred years has at least improved that much. As we hold the mirror of history up to today's reality, what can we learn?

p.35

Early ballots did not list candidates. Voters had to write in the name of their preferred candidate. After Sun Yat-sen agreed to relinquish the presidency in the first year of the ROC, it was with this type of ballot that Yuan Shikai was elected provisional president.

p.37

At one time people had hoped Yuan Shikai would be "China's Washington." But his lust for power was too great, and he attempted to restore the imperial system with himself as emperor (as pictured). His reign lasted only 83 days.

p.38

In the early years of the Republic, assembly members who represented the legitimacy of the regime were courted, and even bribed, by political factions. This commemorative photo shows various provincial representatives at the opening of the assembly in 1913.

p.39

KMT leader Song Jiaoren was assassinated in 1913. The photo shows him dressed in formal attire for a post-mortem photograph prior to interment.

p.39

Warlord Cao Kun, who started life as a butcher, used silver to buy the presidency. But he ended up as an object of scorn.

p.40

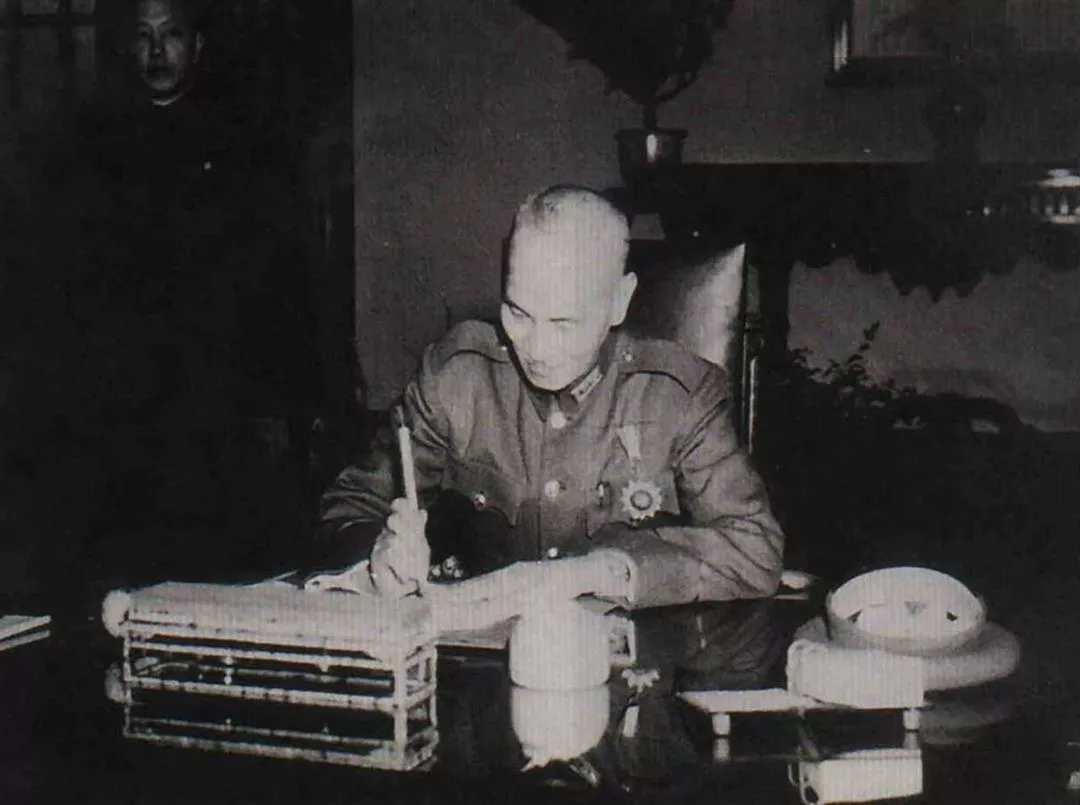

At the end of 1946, Chiang Kai-shek, chairman of the national government, promulgated the Constitution of the ROC, and the era of constitutional government formally began the next year.

p.41

This photo shows Chiang Kai-shek with Taiwan provincial representatives at the First National Assembly to draft the constitution in 1946. They included Li Wanju and Zhang Qilang. Fifth from right, wearing glasses, is Lien Chen-tung, father of current vice-president Lien Chan.

At one time people had hoped Yuan Shikai would be "China's Washington." But his lust for power was too great, and he attempted to restore the imperial system with himself as emperor (as pictured). His reign lasted only 83 days.

In the early years of the Republic, assembly members who represented the legitimacy of the regime were courted, and even bribed, by political factions. This commemorative photo shows various provincial representatives at the opening of the assembly in 1913.

KMT leader Song Jiaoren was assassinated in 1913. The photo shows him dressed in formal attire for a post-mortem photograph prior to interment.

Warlord Cao Kun, who started life as a butcher, used silver to buy the presidency. But he ended up as an object of scorn.

At the end of 1946, Chiang Kai-shek, chairman of the national government, promulgated the Constitution of the ROC, and the era of constitutional government formally began the next year.

This photo shows Chiang Kai-shek with Taiwan provincial representatives at the First National Assembly to draft the constitution in 1946. They included Li Wanju and Zhang Qilang. Fifth from right, wearing glasses, is Lien Chen-tung, father of current vice-president Lien Chan.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)