Put them to the torch

What will happen to his books in the future? "Put them to the torch!" This is Lin's idea of a joke, but it also reveals the understanding of a true man of learning that nothing, in the end, is all that important.

"I've seen very clearly in this business that its virtually impossible to pass one's books along to the next generation." Lin compares old books to old homes. Outsiders will say what great value the old house has, but those inside will want to lear it down and build a new one. That's the way old books are. The person who collects them sees them as precious, but the one who grows up surrounded by them might treat them like garbage.

Lin doesn't think about the future. He's also in no hurry to publish his research. Lin just keeps on collecting materials and doing research with what he finds, step by step. He sees that the sources of old books are drying up, and that it's getting harder and harder to sell them, but he isn't worried. Lin says that he will keep going as a bookseller as long as he can, and when it's no longer possible to do business he'll move back to the countryside to concentrate on reading and research.

Some say that you can tell the level of civilization of a place by checking out its old book shops. With a bibliophile like Lin Han-chang around, there is that much more hope for the carrying on of our culture.

[Picture Caption]

p.46

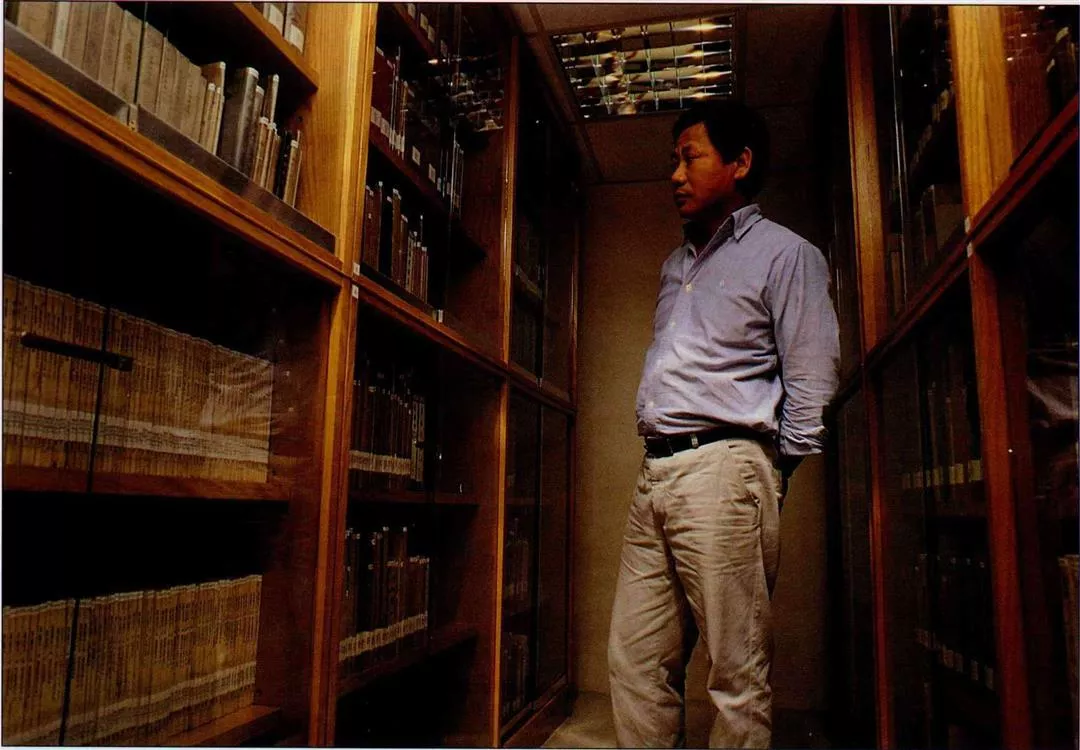

"Bookworm"? "Underground PhD"? Lin Han-chang shrugs off others' taunts and praise.

p.47

(right) Pai Cheng Tang is where Lin earns his living,and also where he does his research.

p.48

As well as second-hand books, Pai Cheng Tang also sells art and curios.

p.49

Buddha figures, furniture, prints, posters, cigarette cards, even old clothes--Lin Han-chang collects anything old.

p.49

"Books hold riches in full store." For Lin Han-chang, they are his whole life.

p.50

For Lin Han-chang, this edition of Inscriptions on Ancient Currency with its beautiful case and cover is one of the favorite books in his collection.

p.51

"I'm always tidying up, but I never get to the end of it!" The ordered chaos of Fan Tien Ko conceals many treasures.

p.52

Giving away books he couldn't bring himself to sell, Lin has donated some of his painstakingly amassed collection of books on Taiwan's history to the Wu San-lien Foundation for Taiwan Historical Materials.

p.53

Lin is aware that his collection may not be valued by his heirs, so though he loves good books he does not cling to them.

Lin is aware that his collection may not be valued by his heirs, so though he loves good books he does not cling to them.