At the Cutting Edge: Yang Shiyi's Quest for Happiness

Liu Yingfeng / photos Chuang Kung-ju / tr. by Phil Newell

February 2017

Small figures dance with joy; glittering stars fill the red background; flowers and trees burst forth in all their glory…. Every detail of this large sheet of red cloth represents the hopes and wishes that paper cutting artist Yang Shiyi sends out to his audience.

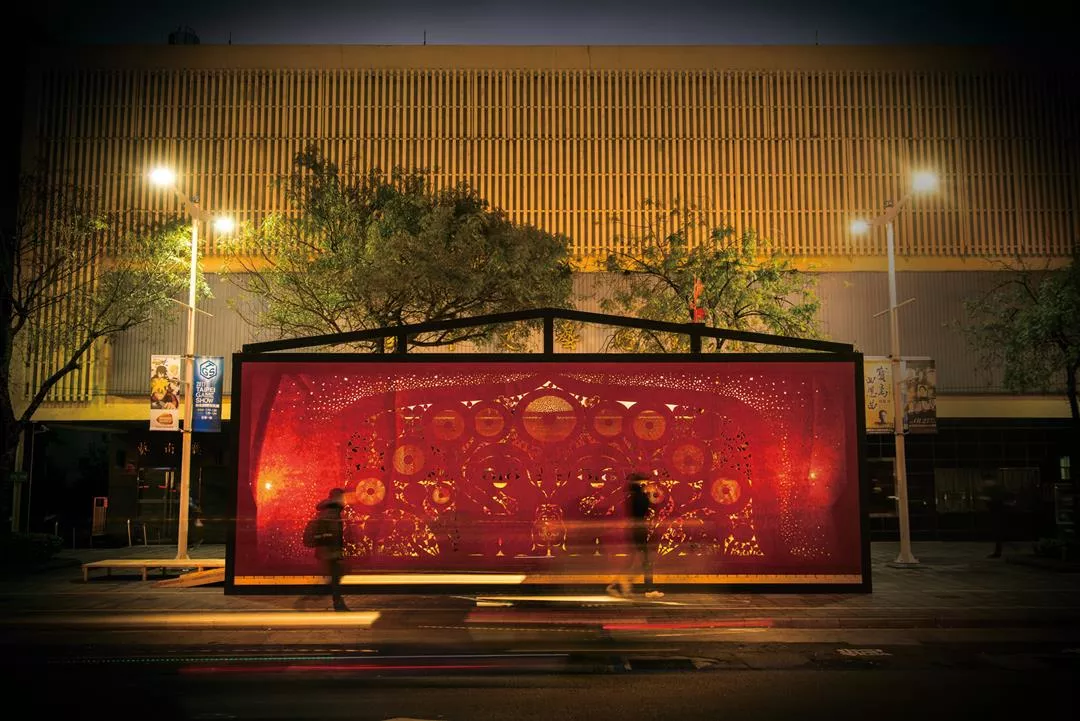

To mark the arrival of the Chinese New Year, Yang combined his paper cutting creativity with the theme of family to create a festive lantern for the streets of Taipei. Knowing that family and friends gather at the New Year, Yang invites everyone to come down to enjoy the world of lanterns and share in their warmth.

The Year of the Rooster is here! An ambience of joy and bustle fills the streets.

On Zhonghua Road in Taipei’s Ximending area, a large red steel weather vane in the shape of a rooster stands atop a temporary structure, gaily turning back and forth in the breeze.

Below the weather vane, a wall ten meters long and three meters high is covered all over with a red cloth, into which delightful images are cut. In the center are two human figures, while stars fill the area above their heads. At the bottom of the cloth, warm light shines through, casting moving shadows of the visitors inside. On the lower rear wall of the structure, next to a stylized cut silhouette of a flourishing tree, the entire surface is covered with “Words for My Family”—family greetings collected from ordinary people.

This house-like structure, entitled Family, is in fact a festive lantern, created by paper cutting artist Yang Shiyi for the 2017 Taipei Lantern Festival, which celebrates the arrival of the Year of the Rooster. Yang was inspired to create this family-themed work by a play on words: in Taiwanese, the word for “rooster” or “chicken” (gei) sounds the same as the word for “family” or “home.”

Yang’s work allows people to literally enter this “family home” and become part of the lantern. “I decided to build a family residence for the Year of the Rooster because I hope that when people gather for the New Year holiday, they will remember that the most beautiful of all lamps is the one that shines at home. And I hope that after everyone admires the lanterns and enjoys their family get-together, they will carry that beautiful strength with them back out into society.”

The work contains a metaphorical wish to all for well-being and happiness. It is made in the cut-paper style that Yang created out of more than a decade of self-doubt and struggle when he took up this art form in 2013.

To mark the arrival of the Chinese New Year, Yang combined his paper cutting creativity with the theme of family to create a festive lantern for the streets of Taipei. (photo by Chuang Kung-ju)

Goodbye to anger

Yang, who studied first in the Department of Visual Communication Design at Kun Shan University in Tainan and then in the graduate school of National Taiwan University of Arts, was a prodigy during his student days. He won countless awards before the age of 27. But he was not happy. He explains: “Although I won a lot of prizes, there was one accolade I couldn’t get: my own self-approval!”

During his childhood Yang was separated from his parents for over ten years, and during those days of living in other people’s care, the naturally sensitive boy became filled with anger and insecurity. The creative world, with an absence of fixed and rigid standards, became his outlet.

Unable to draw, Yang turned to photography. His photographs from that period—cryptic works filled with a sense of alienation—show scenes from his inner life.

One day Yang happened upon a collection of books on paper cutting art, printed by Echo Publishing Corporation. He felt very attracted to one of the works inside, with its clean, simple lines and splashy colors. Imagining that the author must be a very happy person to produce such creative works, a curious Yang decided to find out for himself.

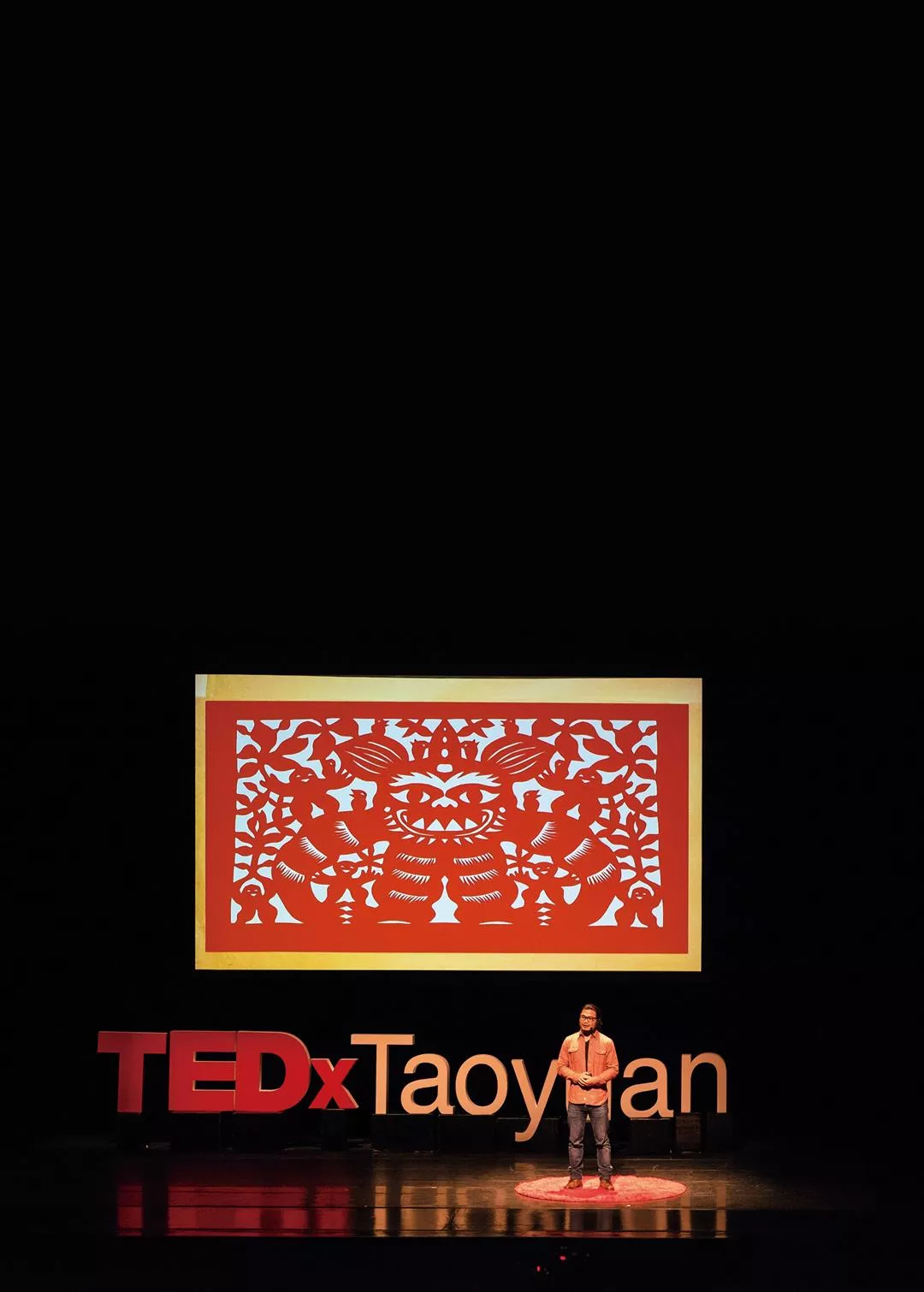

He applied for a grant from the Cloud Gate Dance Theater under their “Wanderers” program, and went off to remote Shaanxi Province in mainland China, in order to visit for himself the source of the work in the book. But when he got there, he was dumbfounded. It turned out that the cut-paper composition came from Ku Shulan, an elderly lady living in Shaanxi, whose photo Yang showed at his 2016 TEDxTaoyuan talk. Ku, completely white-haired by the time Yang met her, lived in a simple house in the loess region of Shaanxi, with yellowed newspaper covering the walls, and a bed knocked together from some odd planks of wood. A small stone slab was her only platform for drafting and cutting her works.

Her life was harsh, and her past even rougher. At age four she was sent to another family as a bride-in-waiting, and she was forced into a loveless marriage at 17. Incredibly, her hardscrabble existence did not diminish the high spirits and joy of her creations. Everywhere in her works you could see dancing people, bright colors, and a spirit of jubilation.

“She had more reason to give up on life than I did. Why didn’t she? Maybe because she saw beauty in the world.” After his three-month journey ended, Yang felt much more at ease, but still he had not even once put his hand to actually cutting paper.

For the next seven years, Yang returned to his alma mater in Tainan as a lecturer, where he started from scratch in relearning how to get along with himself and lived an unostentatious life. It was only when his girlfriend happened to casually make a request that he finally stopped procrastinating and started doing creative cut-paper work. Equipped with nothing but a simple pair of nail scissors, he produced his first work, built around the shape of the Chinese character xi (喜), meaning “happiness” or “well-being.”

At a point where Yang had only produced seven finished products, already a corporate sponsor appeared, inviting him to open a cut-paper workshop, after which firms began showing up in droves to commission works and invite him to participate in shows.

“New Year’s Beast”

Happiness at the cutting edge

As he continued to create, Yang’s works took on a uniquely different style from his past oeuvre. They were not accusatory or dissatisfied with the world, and the lead actors in his large red cut-paper works always beamed—smiling while standing in the middle of a crowd; smiling while gazing at the sky; smiling while embracing…. “That’s because what I want to bring to people is happiness and hope!” Yang explains.

And behind each of these works that make people happy is always a heartwarming story.

Take for example Yang’s 2015 piece Nian Shou (“New Year’s Beast”). Whereas traditionally the nian shou—a creature that emerges at the new year to spread chaos—is portrayed as fierce, with bared fangs and threatening claws, to be warded off with firecrackers and door amulets, Yang depicted it as round and jolly, with a laughing face. And he even thought up a backstory for it.

In Yang’s version, the nian shou is a warm and friendly critter. He bares his teeth and waves his claws only to encourage children who have moved away from home to hurry back to be with loved ones. The firecrackers and lanterns are there to express the profound appreciation of parents to the nian shou, as if to say: “Thank you! Thank you for bringing them back to us!”

Yang’s motivation for rewriting the book on the nian shou is that he saw many people around him weighed down by mutual misunderstanding, so he decided to use paper cutting art to promote straightforwardness, as a gift to those who are willing to bear the burden of misunderstanding for love.

For the winter exhibition of installation art at the New Tile House Hakka Cultural District in Zhubei, Hsinchu County, a giant cut-paper work in canvas, 14 meters high and seven meters wide, seems to reduce viewers walking past it to insignificance. This is a piece entitled Grand-Uncle’s Wishes, which Yang produced based on the theme of “thanksgiving.”

In Hakka tradition, the appellation “grand-uncle” is a term of respect used by a younger person for an older man. It is also used for the Earth God, who watches over each home and family. The earth, like the Earth God, is always there, eternally a companion to ordinary folk, yet is normally silent, so that people forget to treasure it. Yang created this gigantic work not just to make something big as an end in itself, but in the hope that when people raise their faces to look at the complete piece, they will think of the earth beneath their feet.

“Without a story to tell, I can’t put hand to work,” says Yang. He wants every creation he makes to tell a story, so as to move people to think and feel. “Paper cutting is just a kind of handicraft or skill, but through it I want to tell stories and bring some increment of change to society.”

This giant-sized cut-paper work by Yang Shiyi is entitled Grand-Uncle’s Wishes. Exhibited at the winter show at the New Tile House Hakka Cultural District in Zhubei, Hsinchu County, it is a call for people to treasure the earth. (courtesy of Yang Shiyi)

Beauty is not the only criterion

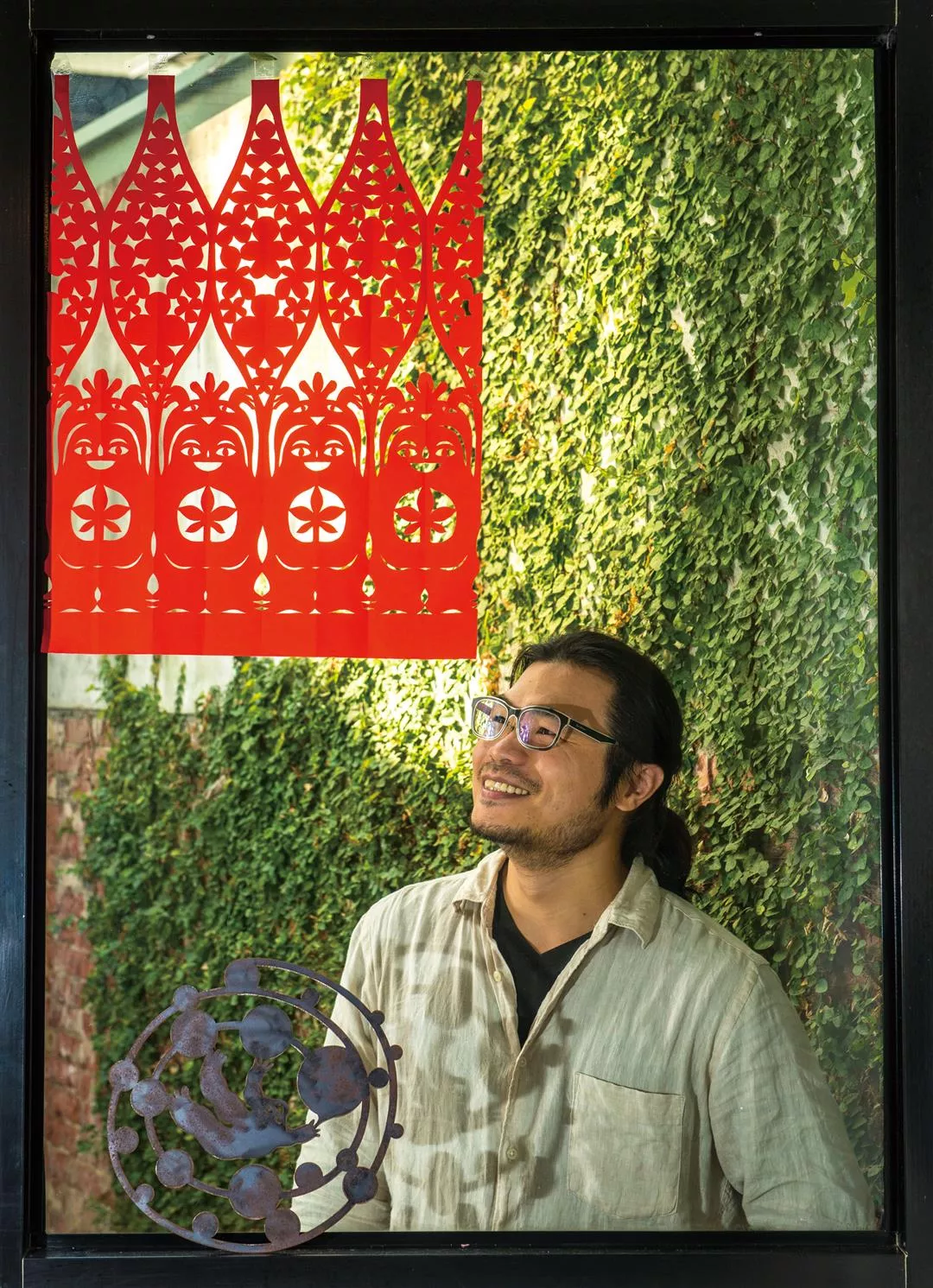

“Not very traditional.” That’s the initial evaluation of Yang’s works you hear from many first-time viewers. Yang’s approach—defined by bold lines, a clean but dashing elegance, and simplified, stylized subjects—is the result of very deliberate culling. When he drafts an underlying pattern, as soon as he sees any traditional motif, he immediately throws it away without hesitation. “‘Faithful to tradition’ is just another way of saying ‘too lazy to come up with creative ideas.’”

Pasted onto the window glass of Yang’s studio are a number of stylized cut-paper flowers, each markedly different from the others, and the whole wall is covered with rough drafts. This year, for a series of works he has been commissioned to make for Taishin International Bank, Yang will do his take on cut-paper blossoms for the first time. In order to find just the right flora, Yang produced no less than 50 patterns. Others might look at the results and see exquisite pieces of art, but not one has yet gotten over the high bar Yang sets for himself.

Yang doesn’t think that beauty is the one and only criterion. “In paper cutting art, beauty is actually pretty easy to achieve. But if you want to make people think and feel, it’s hard. As a form of visual expression, cut paper has limitless possibilities for embellishment and adornment just to fill space, but that’s not necessarily what people want.”

The figures in Yang’s works are always smiling or laughing happily. (courtesy of Yang Shiyi)

Learning to collaborate

The Yang Shiyi of the present day still has moments of anguish and anger. But compared to the past, he has more of a sense of gratitude toward the world and knows that satisfaction with life starts from within. Now that he has opened his heart, everything he sees is like blossoming flowers, and that has allowed him to open himself to collaboration with others.

In May of 2015, Yang worked for the first time with Istheatre Labo, crafting cut-paper backdrops in cloth for a dance piece. This was his first encounter with spatial design, and the first time he took on the challenge of creating giant cut-paper works. Though previously he had always worked alone, for this project he had to recruit assistants to help out.

Two months later, Yang accepted an invitation from the Tainan City Government to create a work on the theme of “royal poinciana” (the flowering tree Delonix regia), as a sort of visual metaphor for the city. There is one photo from that experience which Yang loves to pull out so he can share a story with people. There is an enormous sheet of red paper with a dozen or so assistants kneeling or crouching on it, working with their heads down in concentration. Looked at from a distance, the group takes on the appearance of a caterpillar, climbing up a brilliantly flowering royal poinciana.

What Yang likes about the photo is not just the image of focused teamwork, but also the attitude of humility and respect toward labor that is captured in the shot. “The Taiwanese word for ‘work’ sounds very similar to the word for ‘emptiness.’” Yang, who has continually had to rethink his place in the world, has finally found the answer: “For every individual on earth, it’s as if each person is using the work that they are responsible for to continually fill in the ‘emptiness’ in the world.”

For the work Family for the Taipei Lantern Festival, Yang again opted for a collaborative project, in partnership with the TOGO Rural Village Art Museum in Houbi District, Tainan, and the WeDo Group in Taipei City’s Dadaocheng area. Yang handled the cut-paper artistic creation, while Chen Yuliang, executive director of TOGO, took care of spatial arrangements, and WeDo was responsible for the lighting.

Yang, who had done all his previous creative work on his own, never imagined he would be using the teamwork model he uses today. “When you acknowledge that you don’t know what you are doing, then a team takes shape,” Yang says.

“I believe that with these two hands I can bring people happiness.” Yang Shiyi’s works are seeds of hope that he wants to scatter throughout society. Especially now, at the start of the Year of the Rooster, he hopes that people who see his works will not only feel joy, but believe in themselves—believe that they too, with their own two hands, can bring happiness to others.

Yang isn’t afraid to experiment when it comes to the lines and pen strokes of his draft designs. If the result doesn’t “cut it,” he just throws it out!

Committed to fully experiencing life, Yang Shiyi puts extreme concentration and effort into every stroke of his knife.

In his workshop, cut paper has become the medium through which Yang and his team can together search for beauty and happiness in life. (courtesy of Yang Shiyi)

A splash of auspicious red replete with joyful dancing: Every detail of Yang Shiyi’s works carries a pinch of the pleasure and warmth he wants to bring to everyone. (courtesy of Yang Shiyi)

Yang Shiyi used to be filled with anger and dissatisfaction, but today he has found peace of mind through his art. (photo by Chuang Kung-ju)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)