Whose side are you on?

When the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, not a word was mentioned in the media in Taiwan. And when Japan admitted defeat and prepared to surrender, there were some Taiwanese who turned off their radios because they thought that the emperor's surrender speech (which, among other things, called on people to "struggle" and "unify") was just the same old song-and-dance about the "sacred punitive war." In his memoirs, the well-known attorney Chen Yi-sung recorded just how "absurd" the ending to the war seemed. With that broadcast, the "citizens of a defeated power" overnight became "citizens of a victorious power."

When the events of those days are brought up, many older Taiwanese would prefer not to look back. As Chen Chin-tang, an elderly Taiwanese man who fought in the Japanese army, says with deep emotion, "In those days I was completely confused. I couldn't even tell myself which side I was on!"

[Picture Caption]

P.9

By the time of the formal outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war, Taiwanese had already been under Japanese colonial rule for 40 years. Though the vast majority still felt loyalty to China, under Japan's high-pressure rule it was difficult to express such feelings, and Taiwanese felt very internally divided. (photo courtesy of Chang Wen-yi)

P.10

After the September 18 Incident, the Japanese held a press conference in Shenyang at which they displayed alleged evidence--damaged rail ties, military equipment--that the chinese had sabotaged a Japanese railroad. (photo courtesy of the Kuomintang Department of Party History)

P.11

During the battle for Shanghai in 1937, a child who has just lost her mother cries next to a railroad track in Shanghai shortly after the railroad station was bombed by the Japanese. Her father, holding another child, crouches at her side.(photo by Wang Hsiao-ting, courtesy of the Armed Forces Museum)

P.12

A news photo taken by the Japanese after the occupation of ROC government buildings in Nanjing. The caption reads, "The Japanese flag flies over the capital city of Nanjing. . ., set fluttering in the clear blue sky by the new hope of East Asia." (photo taken from Asahi Shimbun)

P.13

In 1937, Japanese soldiers occupying Nanjing massacred 300,000 civilians, an act that Chinese cannot forget. (photo courtesy of the production team for the TV documentary series One Inch of Land One Inch of Blood)

P.13

During the Rape of Nanjing, Japan's own newspapers proudly reported on killing competitions among the Japanese soldiers. The officer at left killed 106 people, the one at right, 105. They were having a contest to see who could be the first to kill 150. (photo courtesy of the Kuomintang Department of Party History)

P.14

A photo from the Japanese media taken after the capture of Wuhan. The caption reads, "Raising high the slogan of building a new order in East Asia and promoting cooperation between Japan and China, citizens of Hankou attending a 'National Salvation Meeting' swear to 'rejuvenate Asia.'" (photo taken from Asahi Shimbun)

P.15

Taiwan also had its share of propaganda photos with the theme of "soldiers love the people and the people respect the soldiers." This photo was taken in 1943, during the last phase of the war, when economic conditions in Taiwan were most severe. (photo courtesy of Chen Ching-fang)

P.16

Near the end of the war, a large number of Taiwanese were conscripted into the Japanese army. One of them (first at left) was the uncle of Wu Po-hsiung, who is now the secretary-general of the Presidential Office. (photo by Teng Nan-kuang, courtesy of Teng Shih-kuang)

P.17

The Taiwan Courage Corps was active in southeast China, doing medical, propaganda, and other tasks in the war against Japan. (photo courtesy of the Kuomintang Department of History)

P.17

During the war, the Japanese authorities in Taiwan initiated a campaign to encourage women to sew "thousand-stitch cloths" for Japanese soldiers at the front. (photo courtesy of the Kuomintang Department of Party History)

P.17

A booklet entitled "The Current Situation of Imperial Citizens," which attempted to indoctrinate Taiwanese through a question-and-answer format. (photo courtesy of the Ilan Historical Museum)

P.18

In this photo, taken in the last stages of the war, a neighborhood leader (clad in tuxedo) from Luotung in Ilan County leads citizens to the train station to receive the cremated remains of local boys killed overseas. During the war, about 200,000 Taiwanese soldiers were sent overseas, with more than 50,000 killed or missing in action. (courtesy of Chen Huang)

P.19

The ceremony for the acceptance of the Japanese surrender for the area of the China Theater consisting of Taiwan Province was held at the Chungshan Hall in Taipei on October 25, 1945. (photo courtesy of the Kuomintang Department of Party History)

P.20

At meetings of Taiwanese veterans of the Japanese army, both the Japanese and ROC flags are hung. "Who am I?" The doubts and disputes that still exist about national identity in Taiwan can only be understood by going back into history. (photo by Vincent Chang)

P.21

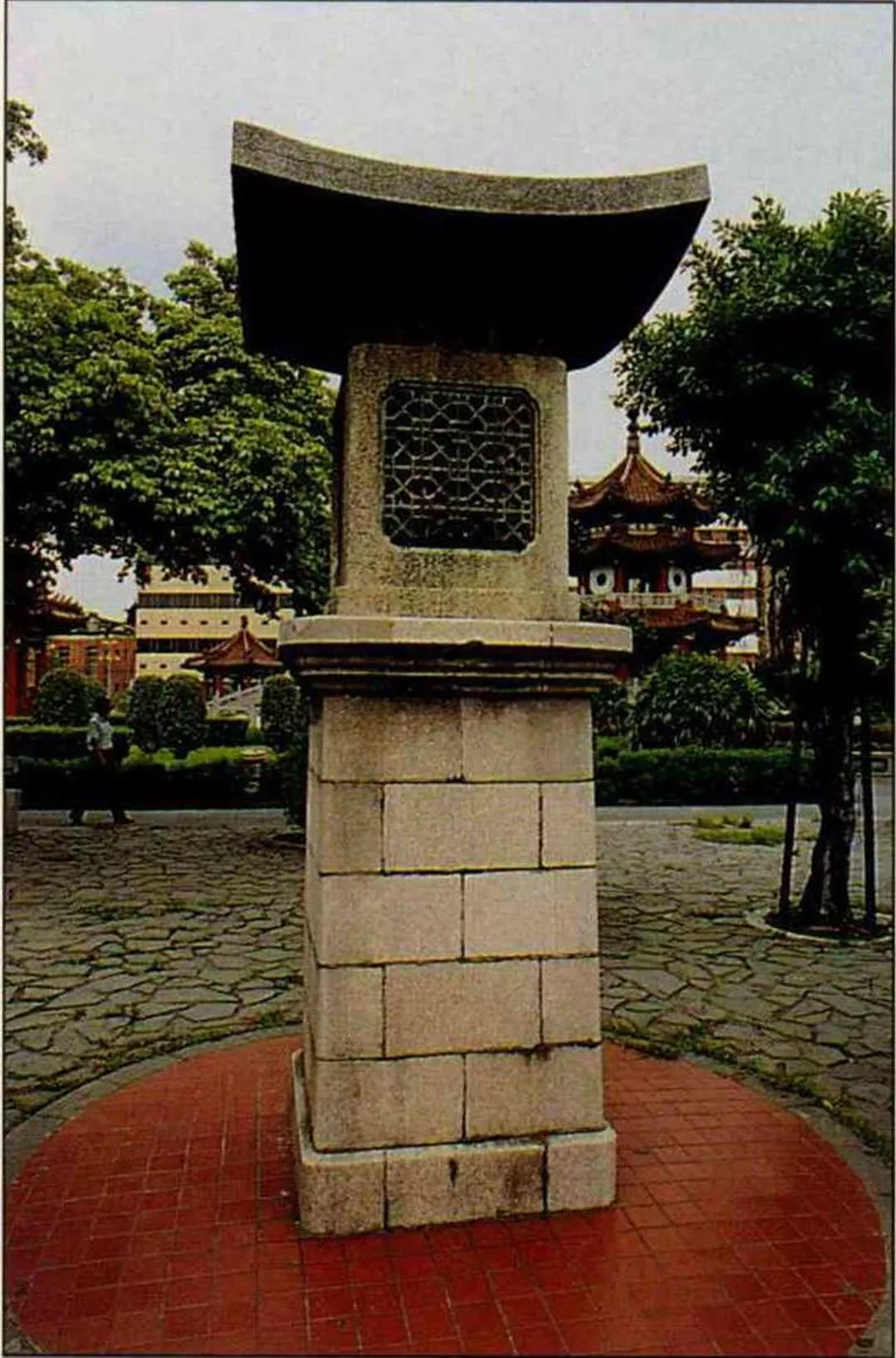

During the war most people got their information from the radio. A public broadcasting tower still stands in Taipei's New Park. (photo by Lin Meng-san)

During the war most people got their information from the radio. A public broadcasting tower still stands in Taipei's New Park. (photo by Lin Meng-san)