An exhibition of works by eight contemporary Chinese illustrators of books for children began a four-city tour of Taiwan this spring. The exhibition, the first of its kind in the ROC on such a large scale, has focused attention on children's illustrators and their importance in the making of books for children.

If, as one children's writer has said, the golden rule of publishing for children is "no pictures means no book," then the illustrator of a children's book must be considered at least as important as its author. In making books for younger children, the illustrator in fact often plays the more important role. And in books for preschoolers, the illustrator may even tell the whole story through pictures alone without a single word of text.

Illustrated books for children have shown considerable growth in the ROC in recent years, both in quantity and in quality. A number of local publishing companies, joined by the Taiwan Provincial Department of Education, have systematically brought out books written and illustrated by local Chinese, while other firms have purchased plates from overseas publishers and produced Chinese editions of foreign originals. Whether foreign translations or local creations, the books are distinguished by the high quality of both printing and content.

"I've become fascinated with a lot of the books I've bought before the children have ever read them," says a Mrs. Chang, mother of two. "They're enlightening and entertaining. They help me understand the way children think and they give me a lot of ideas on how to educate my kids."

A good children's book, in fact, will attract both children and adults--and the interest of other publishers as well. "Foreign publishers now want to reproduce some of our illustrated books," says Ts'ao Chun-yen, editor-in-chief of a local publishing house and one of the illustrators featured in the exhibition.

Writers, illustrators, editors, publishers and consumers have all had a hand in bringing the children's book to its current flourishing state. But illustrators have perhaps made the greatest strides. The earliest illustrated publications for children here were a couple of periodicals for students put out in the early 1950's by the Provincial Department of Education. The purpose was to lead the students away from comic books, which it was felt they were overly infatuated with at the time. For a similar reason, the Taipei City Government later supported the publication of "The Good Student" extracurricular readers, which came out once a month for each of the six elementary grades. Whether they accomplished their stated objective or not, the readers did succeed in causing a lot of artists to take up illustrating for children. "With six editions a month we needed a lot of hands," says Cheng Mingchin, who edited and drew for the publication for five years.

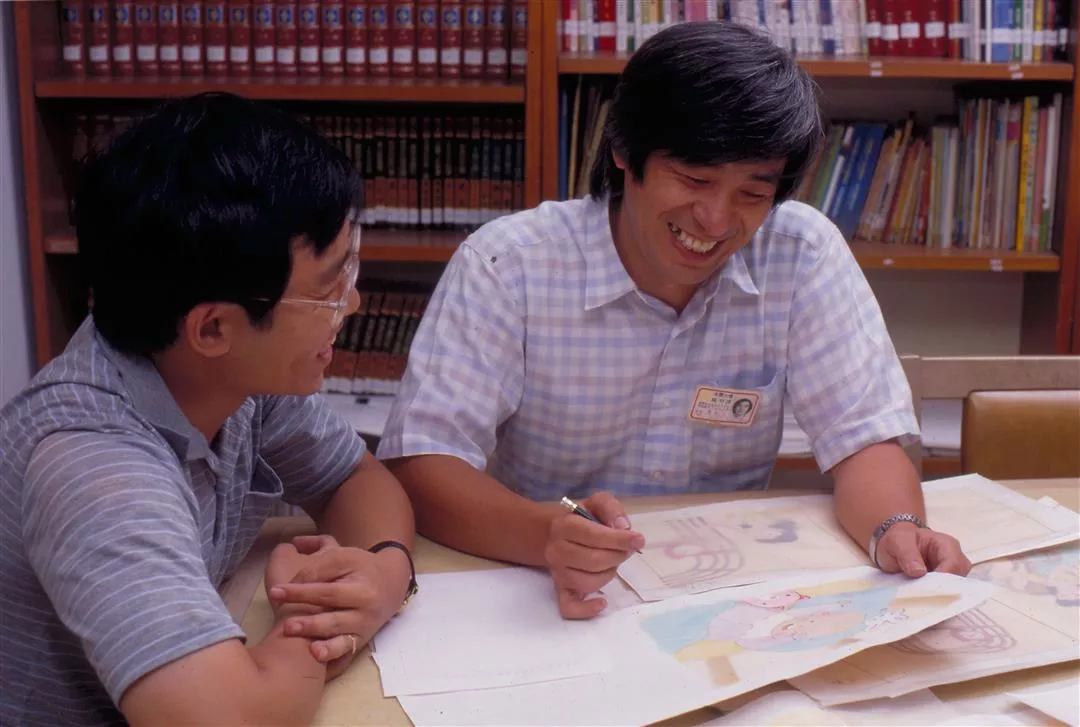

In 1964 the Provincial Education Department, in cooperation with UNESCO, established an editorial board for children's reading material. The art editor was continually seeking out creative talent. He would try to match a suitable artist with each text and discuss with him beforehand what approach he might take. "That way each book had a special flavor all its own," says Ts'ao Chun-yen, who was once art editor for the board. Hung I-nan talked over his first book with Ts'ao just this way. Because it was a historical story, Ts'ao hoped the pictures would have the look of Han dynasty stone rubbings. Using wax pencil, dry brushes and thick paper, Hung produced just the effect Ts'ao wanted.

Through its U.N. affiliation the board exposed local illustrators to the work of their foreign counterparts, stimulating and challenging them. It was while visiting a world exhibition of illustrated children's books that award-winning Tung Ta-shan resolved to take up illustrating for children. "I was very surprised. The illustrations were absolutely equal in standard to paintings for adults."

But stimulation and surprise, they discovered, were not enough--a large measure of enthusiasm and perseverance was also needed. Ts'ao recalls working for the "Children's Monthly" 12 or 13 years ago: "We didn't quibble over money. Everybody knew the work was more or less a donation. The people in charge were getting just token fees themselves." Hung I-nan kept up his drawing from boot camp to discharge while serving in the military. And Liu Tsung-ming, working for a cartoonist he admired, slept in a warehouse.

But they gradually found enthusiasm was not enough either; they also needed to understand their "readers" --kids. Most of them by now had children of their own and had learned firsthand that the youngsters were not to be taken lightly. "When she was small my daughter never thought I drew as well as she did," Tung Ta-shan says. The illustrator can't forget his public. Tung Ta-shan and Chang Chengch'eng show their pictures to their children first.

But it's just this kind of accommodation to children that makes many people think illustrators are merely failed artists for adults. "With our ability and three months practice we could paint as well as that," says Ts'ao Chun-yen, pointing to an expensive ink wash on the wall. "You can only say that each has his special strength. We're not used to expressing the obscure and abstruse but we're more at home than they are with handling what's appealing and interesting." "That's one of the reasons we wanted to open an exhibition," says Cheng Ming-chin, who in an earlier one-man show sold eight works to a bank.

Now that they've proved they're the equal of other artists, will the illustrators rest on their laurels? "He always says if there's time he wants to redo them," Ts'ao says. "He" is Tung Ta-shan. "Liu K'ai is the same; so is Hung I-nan. Actually almost any artist probably has the urge to do it over again."

As to the future direction of children's illustration, there are two schools of thought. Cheng Ming-chin believes in reflecting traditional folk styles and the actual life of the child. Chang Cheng-ch'eng thinks that native or western styles are both acceptable, as long as they're done well. Whatever direction they take, these illustrators and their fellows will try to capture the special wonder and freshness of the world of the child.

(Peter Eberly)

[Picture Caption]

Picture books are favorites with preschoolers.

After he finds a suitable artist, Ts'ao Chun-yen sits down with him to discuss approaches.

A work by Ts'ao Chun-yen entitled "The Year the Dragon Came."

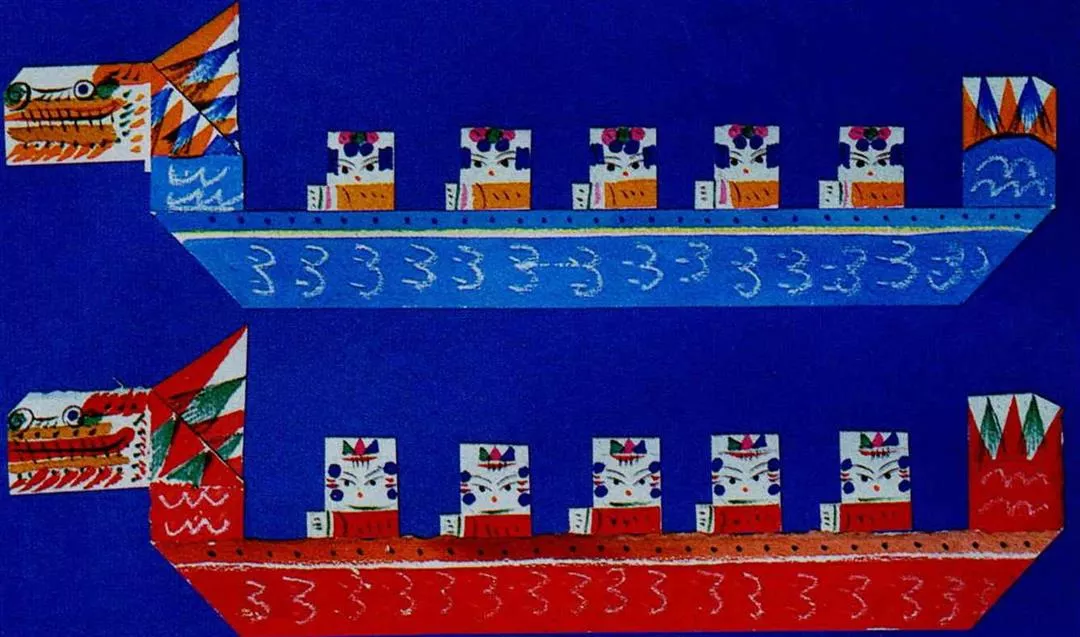

Chao Kuo-tsung's "Dragonboat Race," 1985.

Cheng Ming-chin's "Rooftop Musicians," 1981.

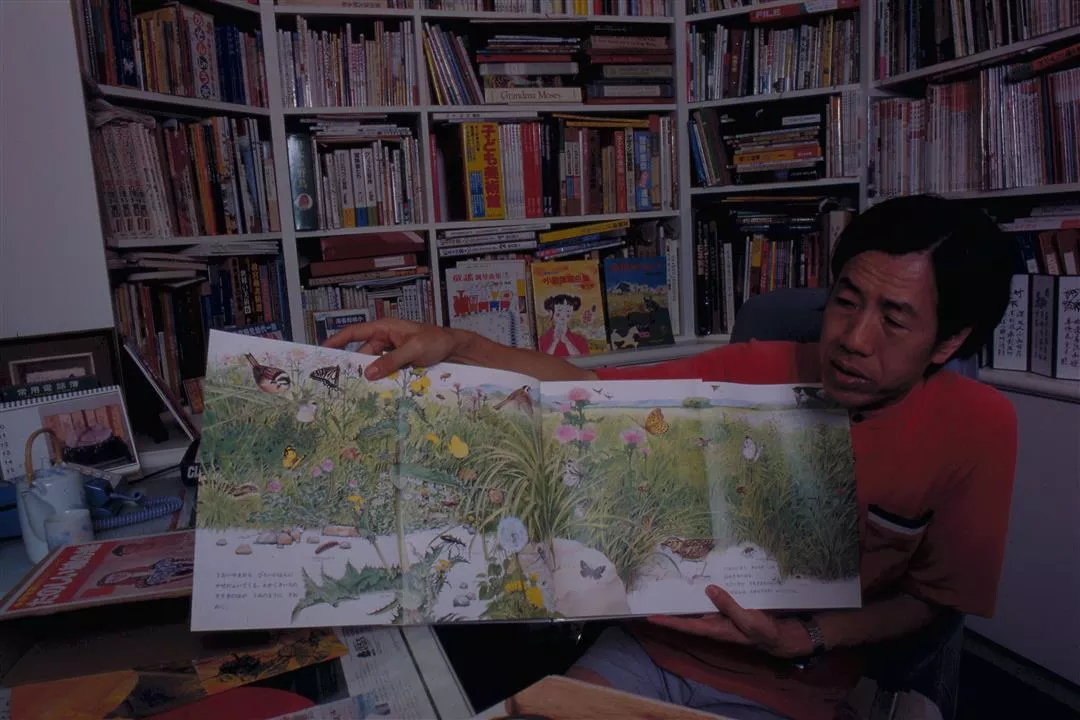

Cheng Ming-chin has been involved in childrens' art education for many years and has investigated both Chinese and foreign picture books.

Hung Yi-nan is one of the few painters who specialize in illustrations for children. He works over ten hours a day in this workship at home.

Hung Yi-nan's "Flying Fish Rowing a Boat," 1984.

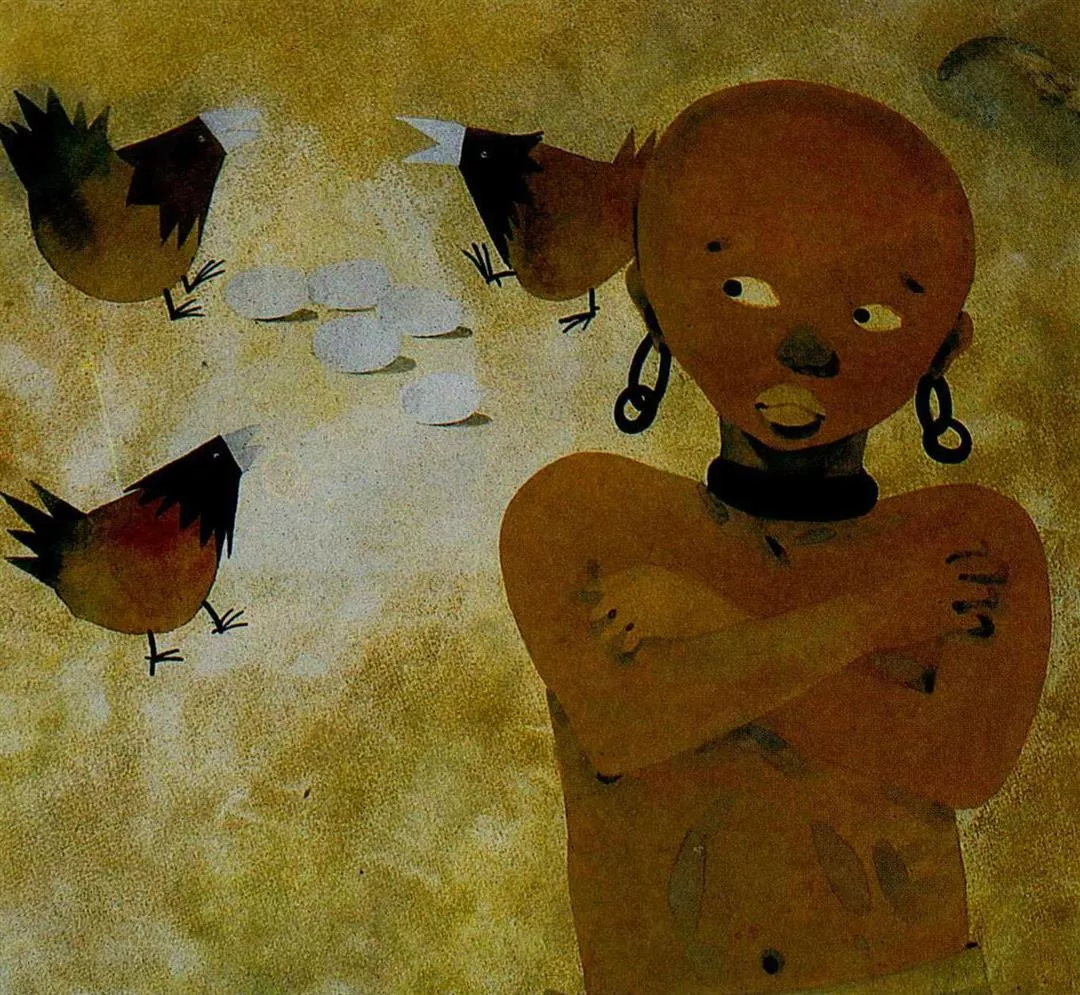

Liu K'ai's "An Egg is Missing," 1984.

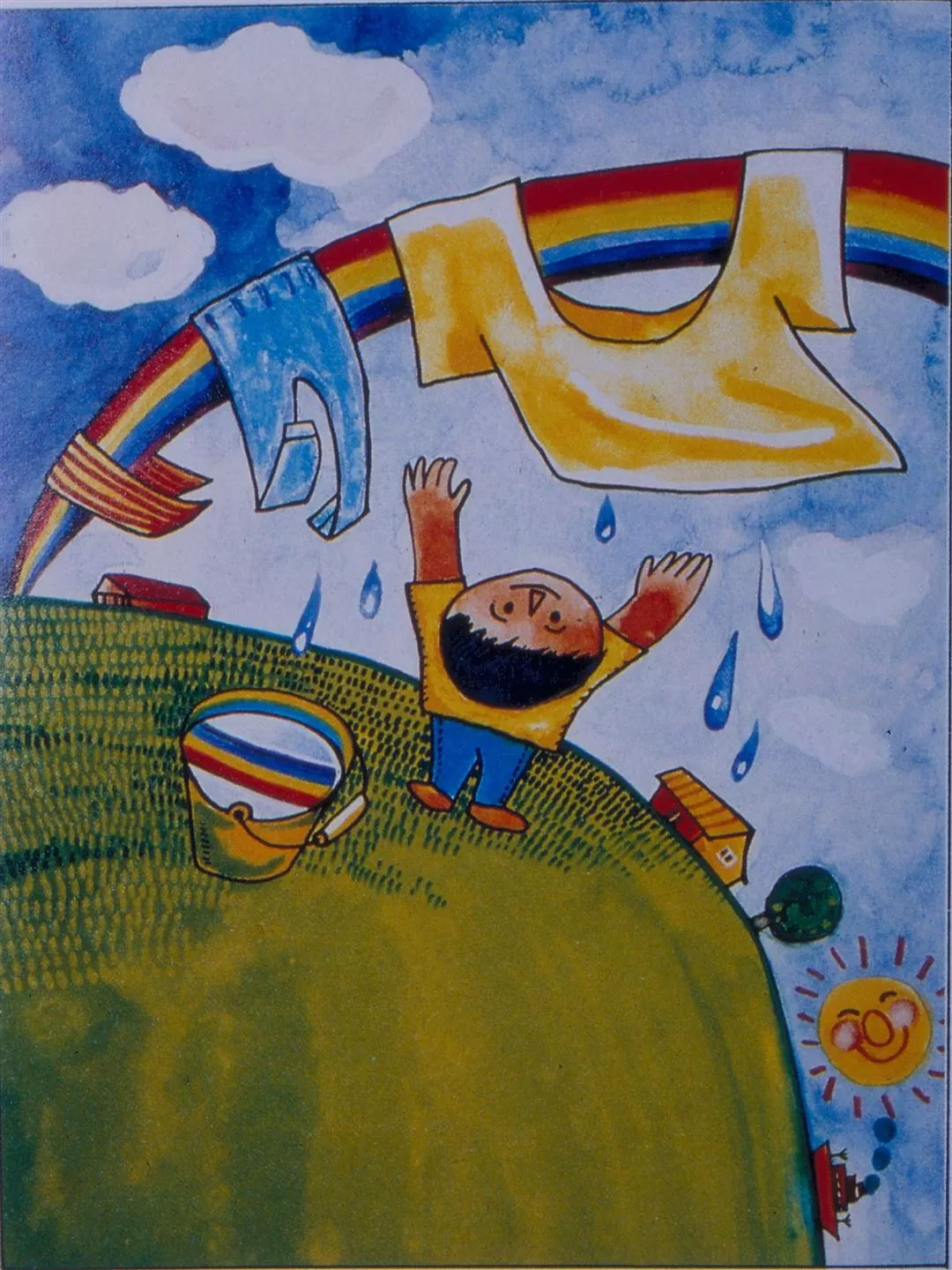

Liu Tsung-ming's "Light Rain," 198O.

Tung Ta-shan and his daughters.

Tung Ta-shan's "The Twelve Animals of the Chinese Zodiac," 1984.

Chang Cheng-ch'eng's Moving House," 1985.

A work by Ts'ao Chun-yen entitled "The Year the Dragon Came.".

After he finds a suitable artist, Ts'ao Chun-yen sits down with him to discuss approaches.

Chao Kuo-tsung's "Dragonboat Race" 1985.

Cheng Ming-chin's "Rooftop Musicians," 1981.

Cheng Ming-chin has been involved in childrens' art education for many years and has investigated both Chinese and foreign picture books.

Hung Yi-nan is one of the few painters who specialize in illustrations for children. He works over ten hours a day in this workship at home.

Hung Yi-nan's "Flying Fish Rowing a Boat," 1984.

Liu K'ai's "An Egg is Missing," 1984.

Liu Tsung-ming's "Light Rain," 198O.

Tung Ta-shan and his daughters.

Tung Ta-shan's "The Twelve Animals of the Chinese Zodiac," 1984.

Chang Cheng-ch'eng's Moving House," 1985.