The Chinese have a saying that "a fallen leaf wants to return to its roots." Earlier emigrants sought to build a new world for themselves overseas precisely in order to return home crowned with success. If they died in a foreign land before they could do so, their wishes were entrusted to a descendant, friend or relative to fulfill.

The Reliquary Hall at the cemetery was built in 1866, chiefly as a temporary resting place for coffins and funerary urns. Back then, a ship used to sail from China to Japan and the Malaysian archipelago once or twice a year specially to carry the remains of the departed back to their homeland, a practice that continued even after the Second World War. Most Chinese viewed the cemetery as temporary quarters for the deceased, not as their final home.

Gradually, however, the cemetery became occupied by long-term guests. Three years ago, after several rounds of consultation, the Yokohama Chinese Association decided to relieve some of the neglect by tidying up more than 600 graves that had long stood uncared for by unearthing the coffins cremating the remains and reburying them in a new location.

During the excavation it was found that some of the departed had not been "resting in peace."

"In graves with southwest-facing tombstones, lime had been spread all around the coffins, and even inside." Wang Ch'ing-jen, the director of the association, explains that southwest is the direction of China and that lime can prevent rotting.

According to his surmisal, these earlier Chinese must have instructed their friends or relatives to have their remains sent back to their homeland after they died, and were buried rather than placed in the reliquary hall because of the concerns that their remains might be destroyed in the war. Perhaps those they had entrusted themselves met with an untimely death, or perhaps because there were no longer ships to take the coffins back . . . so they waited and waited. Waiting for someone to recall them, dig up their coffins, bring them home.

The renovated cemetery faces the ocean, and with their homeland out of sight and out of mind, it seems to be farther away than ever. They have more company underground now, but they still don't understand why those who promised to send them home are so late in coming. . . .

Sometime after six o'clock in the morning, with the temperature just five or six degrees centigrade even though it is still early winter, Takeuchi Kazuo rises. He first opens the doors to the Temple of the King of the Underworld and burns incense for the spirit tablets in Reliquary Hall, and then takes a bamboo broom and begins sweeping under the dark sky, now hinting blue. The swish swish of his broom and an occasional cough float across the one-acre cemetery.

Takeuchi was born in this very place 78 years ago. His father had been the groundskeeper for many years before he died, and afterward his mother took over, but he isn't sure how long ago that was, nor why his parents, both Japanese, began taking care of a Chinese cemetery in the first place.

He used to play in the cemetery as a child, bringing his classmates there for hide and seek, and he would help his parents with the chores. After high school he went to work at a record factory, and it wasn't until 20 years ago, when his parents had both passed away, that he returned to take over their duties. The pay at the factory had been higher, but because of his attachment to the place where he had been born and raised, he didn't feel right with no one taking care of it. Also he was getting on in years, so he decided to come back to this quiet corner away from the hubbub.

The sweeping finished, he recites a Buddhist scripture in a phonetic Japanese version, and even though he has no idea what the words mean, he knows that it is a beneficial prayer for the souls of the departed.

Takeuchi can't read or speak any Chinese, but from the observation of his own two eyes he feels the Chinese have adopted local customs and become more like Japanese. He remembers that coffins used to be brought from Chinatown by crowds of mourners, but now they cremate the remains before sending them to the cemetery, like Japanese. The graves are flat now, Japanese style, instead of the traditional tumulus shape, and they can hold the ashes of six or seven generations. Elderly visitors come with three sets of offerings, for the king of the underworld first, the mountain god second, and finally their own ancestors. But younger people go straight to their ancestors' graves as soon as they arrive, unaware that they should worship those two deities first.

Near dusk, he cleans up the offerings left by visitors and burns any leftover spirit money at derelict graves. He doesn't know what to say to the deceased; he only hopes that they may soon ascend to heaven. In the evening he patrols the cemetery and then sleeps alone in a room adjoining the office. No ghostly visitations or supernatural events have taken place. "It is very still and quiet here," he says. "I hope I can die here someday too."

For the spirits of those Chinese resting underground, especially those of earlier generations, this cemetery is not home; home lies to the southwest, across the sea. But it is for Takeuchi. Their definitions of home may differ, but for him and them alike, the idea that "a fallen leaf returns to its roots" is the pretty much same.

[Picture Caption]

Even though a loved one may stop by for a visit, their dreams of returning home one day remain unfulfilled, alas.

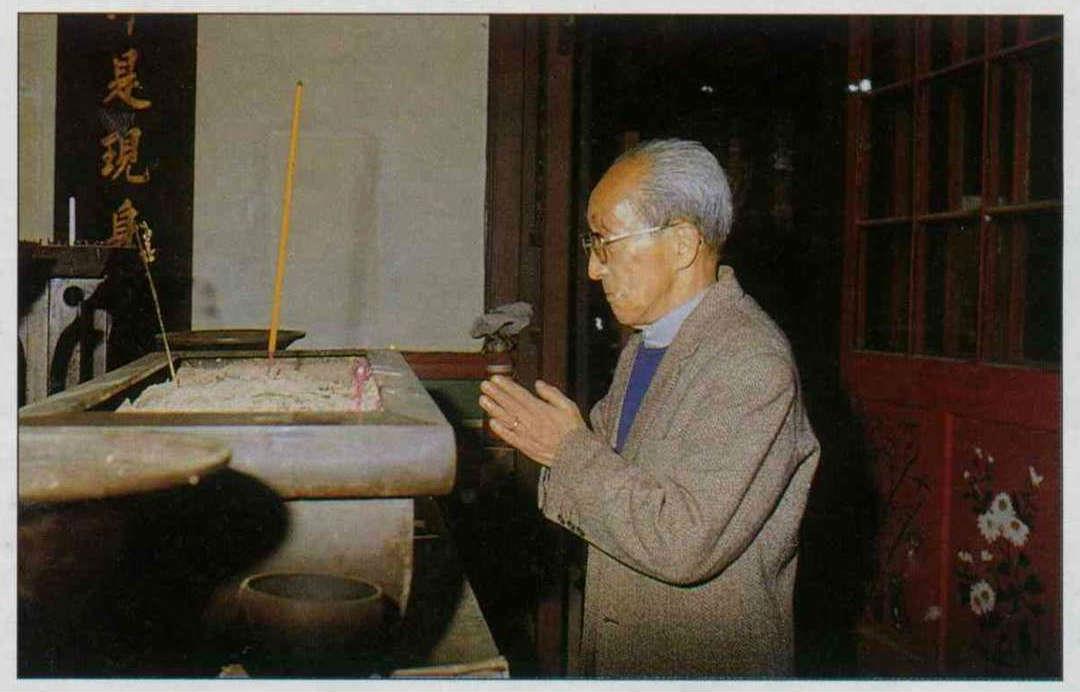

Takeuchi Kazuo goes to the reliquary hall every morning to burn incense to the wandering spirits, in the hope that they may ascend more quickly to heaven.

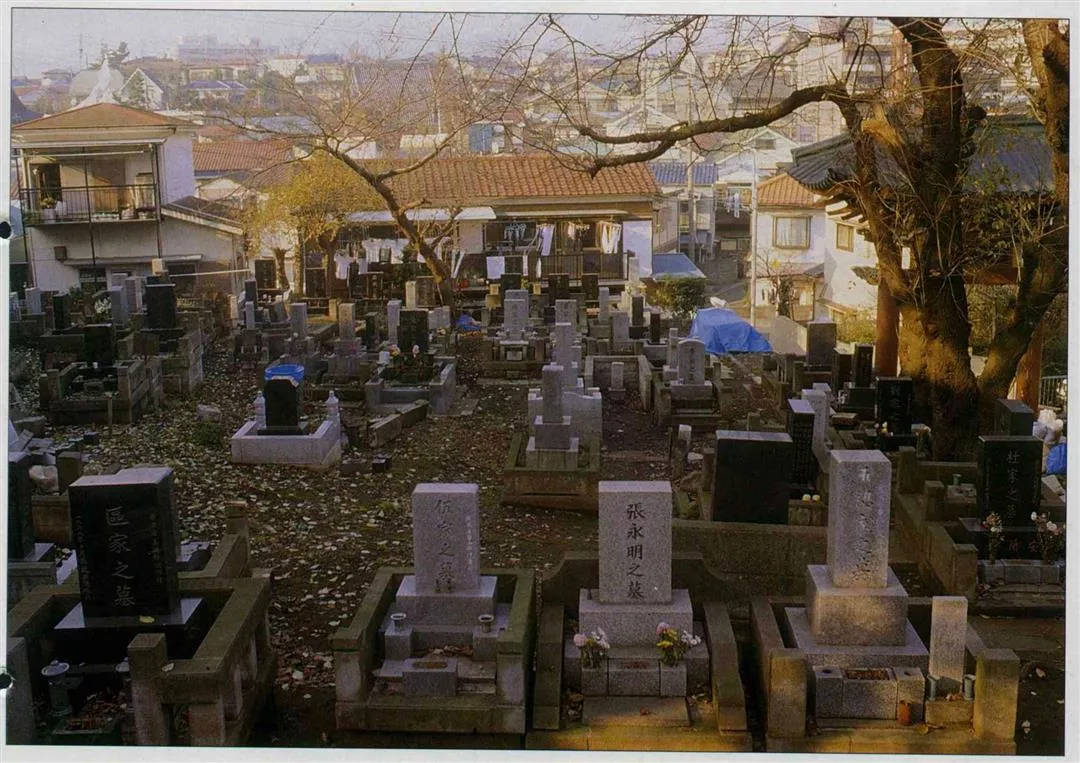

Under the withered branches of cherry trees, the spirits of homesick Chinese sleep the big sleep.

Takeuchi Kazuo goes to the reliquary hall every morning to burn incense to the wandering spirits, in the hope that they may ascend more quickly to heaven.

Under the withered branches of cherry trees, the spirits of homesick Chinese sleep the big sleep.