According to the old Chinese maxim, "Only the fiercest of dragons can cross the river."

Yet as numerous native animals have with-drawn in step with man's encroachment, some "foreign guests" have seized the opportunity to take over, colonizing a foreign land at man's side.

Who said, "A strong dragon doesn't push out the local snakes"?

According to records kept during the era of the Japanese occupation, more than fifty kinds of fish, including the golden carp and Xenocypris argentea, had inhabited the Tamsui River for generations. There were an additional fifty species that returned with the currents or occasionally entered the mouth of the river. Today the situation has vastly changed.

In 1983 a study on fish in the Tamsui River by the Department of Water Resources of the Ministry of Economic Affairs found that the Tilapia, native to Africa, is now lord of the river. In the area by the Hsiulang Bridge in Hsintien, it accounts for 60 percent of all fish. The pollution gets worse the further one goes downstream, where the proportion of Tilapia in the river rises, exceeding 80 percent in the area by the Chingmei and Chungcheng bridges.

Foreign Occupiers of a Treasure Island: Lets leaf through The History Of the Tilapia in Taiwan: Introduced in the fifties from Africa, in the sixties it was widely promoted for breeding by agricultural and fishing agencies. Afterwards, it entered the rivers from the fish ponds, and in the seventies it constituted 5 percent of all fish in Taiwan, rising to 40 percent in the eighties. Today, one can catch Tilipia fry easily--even in such bodies of water as the Chengching Lake of Kaohsiung.

The Ampullarius canaliculatus is another aquatic outsider, second only to the Tilapia in numbers. At first businessmen introduced this snail for human consumption. Unfortunately, its flavor didn't go over well with Chinese eaters, and its eventual fate was far from that of the Tilapia. After being discarded in the wild, this tenacious fish has thrived by helping itself to crops. Today, in the north or south, during any of the four seasons, you can see its pink eggs on crops within a yard of water.

"The Ilan plain has already been invaded by the Brazilian tortoise," stated outdoorsman Yang Ching-hsing at a research symposium. Sport fishermen have recently been catching such aquatic exotica as piranha and Osteo glossum bicirrhosum which--like the flourishing Brazilian tortoise -- were originally introduced in Taiwan by pet fish stores.

The air above Taiwan is also being transformed. Whether by escaping from their cages or being set free, many foreign species of bird have managed to get up there and fight for their piece of the sky. Ecological photographers and bird watchers from the Wild Bird Society have frequently spotted such nonmigratory "imported birds" as the Brazilian Sparrow, parrots native to South America, and the Mainland hwa-mei (Garrulax canorus canorus).

Among them, first in numbers is the mainland hwa-mei, a bird noted for its vocal abilities. In order to win hwa-mei singing competitions, bird mongers have, in addition to capturing the Taiwanese hwa-mei in the wild, imported large numbers of its mainland cousins. Business for males is very good, whereas females, with neither songs nor buyers, are set free. Today you can see them, far from their mainland homeland, in such places as the Taipei Botanical Garden. They have also begun to seek mates in the wild. Crossbreeding with the Taiwanese hwa-mei, they have created a new species.

A Fierce Dragon Blows Its Smoke: Formosa is not unique in its problem with foreign invaders.

On the American continent, there is an ecological case known around the world. Out of homesickness, early immigrants to America introduced starlings from Europe. Today, in addition to brutally taking over the nests of native birds, starlings congregate by day in farmers' fields outside of cities, where they devour the crops, and at dusk fly in hordes into villages, driving the residents to their wits' ends.

The nearby country of Japan also has learned a painful lesson. Lake Biwa is the largest inland lake in Japan, one that used to teem with life. Since the American large mouth bass was introduced there, native species have gradually disappeared. Later people discovered every kind of native shrimp, crab and fish in the stomachs of the perch. Up to the present, the large mouth bass has been a scourge of the Japanese fishing industry.

In truth, whether man introduces a foreign species intentionally or accidentally--because the climate, habitat and sources of food in its adopted land are all different from its native environment--the newcomer will have little chance to survive unless man feeds and cares for it.

Having lived for generations in its native habitat, however, a species will usually have natural enemies there to control its numbers. When first entering a foreign land, it may be without natural enemies--because other animals have no understanding of it, because it hasn't yet met the animal that can overcome it, or for other reasons--and it will have a chance of surviving. "Even if a species has only a one in a hundred chance, there will always be some that will beat the odds," says Li Ling-ling, associate professor of zoology at National Taiwan University (NTU).

When the Natives Meet the New-comers: This chance exists because the native animals have already lived with each other for tens of thousands of years, resulting in an ecological balance wherein things go along happily and pretty much unchanged. Hence, the natives are no match for tough recent arrivals eager to establish a place for themselves.

"In particular, island animals, which have existed in seclusion from outsiders and are thus less aggressive, often don't know how to run away or what to do when encountering natural enemies from outside," says Yang Ping-shih, professor of plant pathology and entomology at NTU. Island ecologies are more vulnerable than continental ecologies. As a result, Taiwan gives outside species a better chance. Yang Ping-shih cites the example of the mild-mannered Taiwan tortoise, which had existed on the island for countless generations, enjoying an easy and stable existence. "How are they a match for the mean Brazilian tortoise?"

If a tough troublemaker is carelessly brought in from abroad, the native species will find it difficult to defend themselves against it. Take for example the Houttyn, which is used to clean the waste in fish tanks. It can survive even in sewers. Its skin--which is used to make files in its original home of South America--is thick and tough. In addition, its predator, the alligator, does not swim in the rivers of Taiwan. It was very expensive when first sold in Taiwan. Later, because it numbers grew and because it does not die easily, people got bored with it, and it came out of the sewers and into the rivers. "Today its traces can be seen in the Tamsui and Kaoping rivers and in Taoyuan's ponds," says Tseng Ching-hsien, a doctoral candidate in zoology at NTU.

Only One Turnip per Hole: "Island ecologies can be said to support 'only one turnip for every hole.' If there is one extra turnip, you won't be able to find a hole for it," says Yang Yi-jung, also an NTU doctoral candidate in zoology.

For a variety of reasons, outside intruders will not bring "greater variety" to the species of the island, but rather will introduce a new round of "survival of the fittest."

Those who have travelled to Sun Moon Lake will know of the Erythroculter ilishaeformes, which is called the president fish in honor of former President Chiang Kai-shek, who was fond of it. Because the president fish does not protect its young, the eggs it lays on water plants have become easy pickings for the Tilapia. As the numbers of president fish have declined, its price per Chinese pound (600 grams) has risen to NT$1000.

In the long run, several species of fresh water fish, such as the zacco and the smelt, can simply not compete with the Tilapia, which eats anything and protects its eggs. It is of such strength that NASA of the United States has selected it as "a fish for use in outer space."

The Coming of the Cray Fish--a Bad Situation Gets Worse: Foreign guests are also making themselves at home in the sky. A 30-year investigation on birds around the globe, carried out by the International Council for Bird Protection, has found that "inability to compete with foreign species" is the reason accounting for 20 percent of all extinctions, a cause ranking higher than environmental pollution.

"It is not unusual for bird watchers to see mainland hwa-mei mating with Taiwan hwa-mei" says Chen Ye-wang, a senior member of the Birds Association, who is worried that Taiwan's hwa-mei, might soon be facing extinction.

The Phasianus colchicus formosanus, easy to raise and of opulent appearance, is also facing a crisis. Its mainland counterparts, which have been imported, are interbreeding with it in artificial or semi-natural environments, slowly eliminating the special characteristics of the Taiwanese gene pool.

Lacking in natural enemies and with startling powers of adaptability and procreation, these foreign species may also be harmful to man. An early historical example are the rats that crusaders brought back from the Middle East as spoils of victory in the fourteenth century. These rats and the fleas on them were the cause of the plague that decimated more than a fourth of Europe.

Because of a lack of rainfall, there is a shortage of water, in southern Taiwan this summer. While many farmers' fields are already dry, many now face the additional menace of the American cray fish.

Introduced by pet fish stores, the (cray fish) is a giant among species of shrimp--growing longer than ten centimeters--and a fearsome combatant. Regardless of size, fellow occupants of a fish tank all give way to it. Even if a person gets hold of its backside, it can still lurch back and cause injury with its pincers. Following in the footsteps of the Ampullarius canaliculatus and the Houttyn, it has been discarded by man only to thrive in the wild.

The cray fish has another ability of note: it can dig a hole several meters deep. As a result, pesticides are of no use against it. It is also a determined builder of roads--whatever stands in its way gets a good clip from its pincers. When the ridges dividing wet fields are worked over by the cray fish, a field can go dry in one night--much to the exasperation of farmers. Ecologists stand in awe of its destructive powers.

The Ampullarius canaliculatus--Endless Trouble: Nevertheless, the cray fish has just started causing trouble, whereas the evermounting mischief of the Ampullarius canaliculatus has already taken a very visible toll. Since it was released and gained a liking for crops, agricultural experts have done their best to find a natural predator. They have learned that--line man--ducks, sparrows, ants, wild fowl, and insects find it entirely unappetizing.

Five years ago the pesticide industry finally discovered something that could pierce the armorlike shell of the Ampullarius canaliculatus: the expensive TTTA. A manager of a pesticide import company says that while it originally sold 500 kilograms of the stuff over two years, it has sold 2000 kilograms in the past year alone. But the killing this mightiest of pests also takes the lives of lots of innocent bystanders. An area of vegetable fields in the Lanya district of Shihlin that has been set aside for development as athletic park was previously a muddy swampland full of great varieties of native fish. The Council for Cultural Planning and Development had once wanted to set it aside as a "Protected Area for Taiwanese Rumble Fish." But since the arrival of the Ampullarius canaliculatus, farmers have had no choice but to use pesticides once a week. As a result all kinds of aquatic life have died together, and the idea of a protected area has died with them, leaving behind worries about tin pollution.

Protecting Your Own: Whether or not descendants of these foreign invaders can survive and prosper, animals just passing through as well as those coming to stay for good pose a threat to Taiwan.

The year before last, smuggled-in Tibetan Mastiffs that were rumored to have rabies caused public panic. Lately people have been introducing snakes. If an exotic snake that has not been defanged bites someone, there will be no available antidote.

"People are introducing animals unaware of the results of their actions, creating potential crises for which even ecologists will be of no help," says Li Ling-ling.

Besides preventing people from hurting themselves, countries around the world are scrambling to establish gene banks in the hope of preserving their native plants and animals. To prevent competition from foreign species, countries are imposing ever stricter controls on the import and export of wild animals.

Biologists have proven that opportunities for outside species grow more numerous as native species grow sparser. Conversely, the more abundant is native life, the smaller is the foothold available for outsiders. "Beyond limiting the introduction of foreign species to those that are really needed," says Wang Ying, professor of biology at National Taiwan Normal University, "preserving native species is an even more important step in closing the door on these unwelcome guests."

[Picture Caption]

While exotic species may be pleasant to the eye and tasty to the tongue, they bring with them no small number of problems.

Since the mainland hwa-mei entered the skies above Taiwan, the Taiwan hwa-mei has faced the crisis of losing its unique identity as a species.

The ampullarius canalicultus has been the nemesis of Taiwan's farmers.

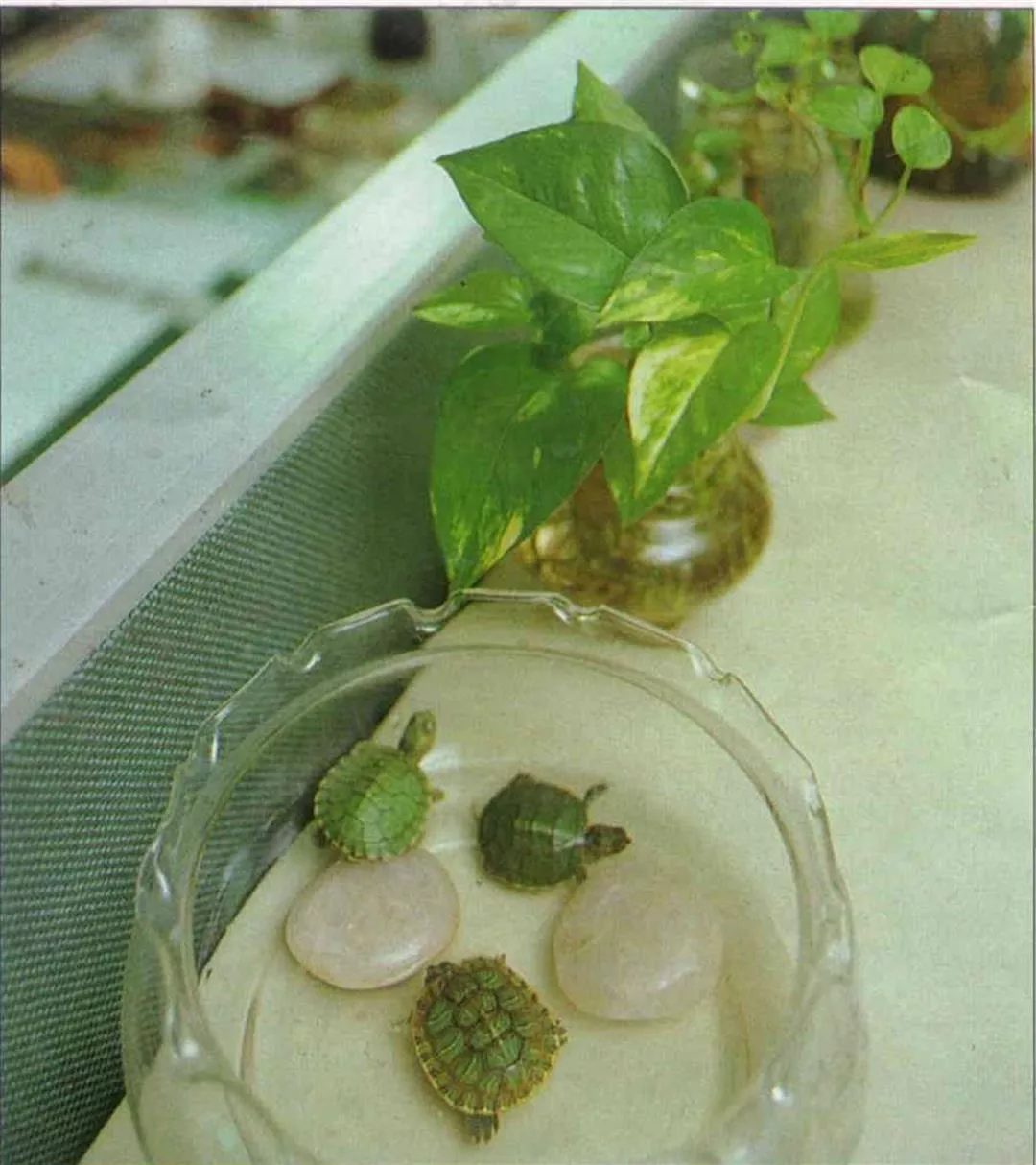

The Brazilian Tortoise does more than take strolls through town. He also plays a major role in the wild.

Originally brought to Taiwan as pets, Brazilian Tortoises have become a threat to native tortoises after some were released by their owners.

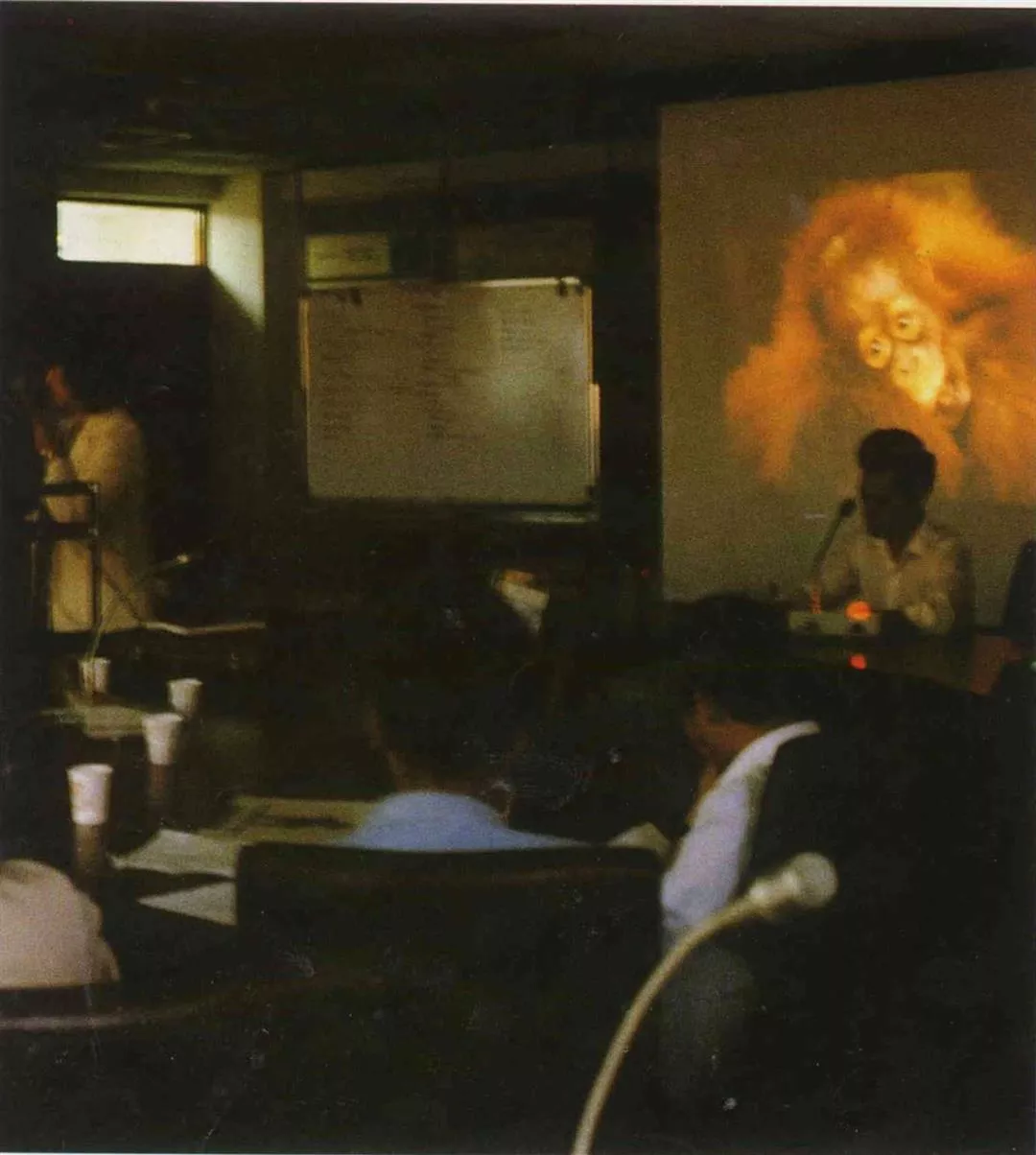

Two years ago businessmen started to smuggle in orangutans. The department of health is worried that they may transmit diseases to humans and has held special public announcement meetings about this problem. (photo by Vincent Chang)

Since the mainland hwa-mei entered the skies above Taiwan, the Taiwan hwa-mei has faced the crisis of losing its unique identity as a species.

The ampullarius canalicultus has been the nemesis of Taiwan's farmers.

Originally brought to Taiwan as pets, Brazilian Tortoises have become a threat to native tortoises after some were released by their owners.

The Brazilian Tortoise does more than take strolls through town. He also plays a major role in the wild.

Two years ago businessmen started to smuggle in orangutans. The department of health is worried that they may transmit diseases to humans and has held special public announcement meetings about this problem. (photo by Vincent Chang)