The recent release of an album featuring both Ami music from Taiwan and aboriginal folk songs from Papua New Guinea has again brought Ami singing into the news. In terms of ethnomusicology, what does Papua New Guinea, far away in the Pacific Ocean, have to do with the aboriginal peoples of Taiwan? And what story does the new album have to tell?

As good a place as any to start is with a new record by the "Betel Nuts." The key figure in the story is an American doctor of musicology-Christopher Roberts.

Christopher Roberts comes from California, and has just turned 40. He has a double doctorate in composition and double bass performance from the Juilliard School, New York. Fifteen years ago he received funding to carry out research in the Star Mountains of central New Guinea and on some small Papua New Guinean islands, the Trobriand Islands. Over the last few years he has collected and written down the words and music of several hundred folk songs.

But Christopher Roberts' story does not end in Papua New Guinea. Nine years ago he came to Taiwan, to study the Chinese traditional stringed instrument the qin. During an excursion, in a hotel in Hualien he heard a performance of singing by the Ami aboriginal 'Api (Chinese name Chang Tsu-hsiang) and others from the village of Ciwidian (Shui-lien in Chinese). Roberts, who often jokingly says that he "lives by his ears," recalls that his immediate reaction was: "How come it's so similar to Papua New Guinean music?" A powerful sense of curiosity led him to step onto the path of researching Ami music.

A big event for 'Mui's family

'Api and his family were one of the keys by which Roberts first unlocked the door to understanding Ami music. In fact, the 'Api family of Ciwidian are no strangers as far as many scholars of folk music in Taiwan are concerned. 'Api's father 'Mui Valah (Wang Chin-tsun), an old Ami chieftain of Ciwi-dian, is known to everyone in the village as one of the best lead singers at Ami Harvest Festivals.

Of 'Mui's twin sons Huegu (Chang Hui-kuo) and 'Api, the one plays guitar to a professional standard, and the other has been described as an excellent singer ever since he was in elementary school. Once he was grown up, 'Api was hired by several tourist "culture villages" in Hualien County as a singing and dancing instructor. He has frequently gone overseas to represent his local area in international aboriginal singing and dancing performances.

A cousin of the twins, Valah Udai, plays the double bass and once put together a rock group. Valah Udai is trained in musical theory, and can write his own multipart scores. He often quips that he is the one among the musicians in the family who "has been most deeply contaminated by Western culture."

Roberts admits that before he came to Taiwan, he knew little about the music of the island's indigenous peoples. It was only after he got to know 'Api and his family that they opened the way for his research into Ami tribal music. He has spent the past seven years shuttling between Taipei, Hua-lien and Papua New Guinea. His greatest hope is that "such beautiful kinds of music and the relationship between them should be known to the people of the world." And putting out a record is the best way he knows to achieve this.

For many years people have been asking 'Api and his family to make records, but they have never allowed themselves to be persuaded. "If they want us to sing a lot of adulterated stuff, for instance with Japanese or Mandarin lyrics, or something too commercial, then we're not interested," says 'Api. He says the reason they agreed to Christopher Roberts' request to make a recording was that "it wasn't just making a record, it was also helping scholarship."

Perhaps partly because of such "scholarly" expectations, even before Betel Nuts was released, it had acquired a very cultured aura.

How are they alike?

The question everyone was most curious about was this: If, as many anthropologists say, the aboriginals of the Trobriand Islands and Taiwan really did share the same origins 1000 years ago, then what features does their singing have in common?

Roberts' research shows that the songs of both Hualien and the Trobriand Islands often end in a repeated series of three emphasized notes, which alert the singers to the end of the song. When one listens to aboriginal singing this peculiarity is easily missed, but when the aboriginal "songs" are written down in musical notation, the feature becomes very striking. Christopher Roberts believes that this is indeed a mark of the common origins of the two cultures.

But not everyone agrees with this view.

Ethnomusicologist Ming Li-kuo says that when comparing two cultures, the fact that one sound is very similar or that this or that musical phrase is the same is generally not sufficient grounds for saying that there is a basic similarity between the two cultures. To cite an example from the past, when one researcher concluded from similarities between a pan pipes melody from South America and one from Tahiti that there had very probably been contact between the two areas, this idea was questioned by many people, because so many examples of such melodic similarities can found in folk music throughout the world that there would be no end to the instances of cultural contact one would have to assume on this basis.

In Ming Li-kuo's view, it is only by studying cultural systems in the context of their original environment, and understanding such factors as the role which music plays in aboriginal life, that one can arrive at a clearer picture of the connections between various cultures.

All for the sake of storytelling

There are indeed many questions of musical theory still to be resolved in comparing the music of these two tribal peoples. But for people listening to the music, it is not difficult to intuitively detect similarities between them.

"The tunes and the voices are very pure!" says Lin Liying, an executive manager with music publishers Trees Music and Art.

"Both in the words and in the music, I feel they are telling their own story," says one woman who went to several successive live performances by the Betel Nuts, and who has listened to the album many times over.

These listeners' ears are sharp. They quickly grasped what the Betel Nuts album is all about: telling stories.

In preliterate aboriginal societies, songs and legends are important ways of transmitting community norms, morals and history. In aboriginal society, family and community memories are preserved by oral tradition.

What people find most enchanting about the Betel Nuts album-the songs collected and published by Christopher Roberts-is this method of "storytelling."

"When wearing an aluvu pouch

When those old men carry an aluvu pouch

What could be inside?

Betel nuts

And mustard leaf

And what's the use of those?

For those old men to brush their teeth with

When wearing an aluvu pouch

When those old men carry an aluvu pouch

What could be inside?

Rice wine

And a shell for a cup

And what's the use of those?

To slowly take their weariness away."

(Aluvu-"The Betel Nut Pouch")

This is a song familiar to people in all the Ami villages in Hualien and Taitung Counties. Most Ami songs have slow and simple melodies, and this one is no exception. According to old Ami people, the content of this song became "fixed" around the time when Taiwan returned from Japanese to Chinese rule (1945).

In 1964 this song appeared in "Ami Folk Songs," an article by folk music researcher Yen Wen-hsiung published in China News-week. The song takes the form of an old man answering an inquisitive child's questions about his betel nut pouch. His humorous explanations serve to teach about the special significance of the betel nut pouch in Ami culture.

"This little betel nut pouch holds so much of the Ami people's love and feelings"-in December of last year 'Api, sporting a brightly colored betel nut pouch of woven cotton, said these words to the audience at a record sales promotion event in the big city of Taipei.

'Api explains that in Ami culture, offering betel nuts is a way of making friends. The betel nut pouch is not only a "highly practical" container for carrying betel nuts and drinking tackle, it is also a cultural symbol.

"At the Harvest Festival, when you put on your betel nut bag, it means you are grown up, and at this kind of social occasion grown-up Ami girls will place betel nuts and liquor inside the betel nut pouch of the man they like best. Hence the betel nut pouch is also called the 'sweetheart pouch.' This forthright, liberated way of making friends has been part of Ami culture since ancient times," says 'Api.

Musicians all

"What could that be?

What could this be?

A necklace

Worn by Wayau

Brilliant as the eyes of the takura frog

How I want her

Really want her."

(Ka Urahan A Radiw-

"What Could That Be")

This song is also very widely known among the Ami people. The very simple lyrics describe feelings of missing a sweetheart. The line "brilliant as the eyes of the takura frog" reveals the aboriginals' understanding of the environment in which they live.

"So good to be drinking

Liquor

Just the ancestors

And me

I go home, swaggering

Sawiriwiri this way

Sawarawara that way

In the center of the road

Drunken and heading home

To a certain violent scolding

From my wife."

(Aso Ai-"So Good To Be Drinking")

Perhaps because this song echoes many aspects of real life in the tribal villages today, 'Api and the others love to sing it, and Huegu has also written a version in Mandarin: "This liquor tastes so good, I gulp it down cup by cup; So I fall into the ditch. When I get home I can't sleep, So I sleep on my wife's thighs. . . ." When they get to this line, the twins and their cousin always burst out into roars of laughter, along with the audience.

When one compares the Ami music of 'Api and his companions to the music from the Trobriand Islands, "their voices seem more rounded and smooth, while the Tro-briand Islanders' voices seem rougher. Could this be because the Trobriand Islanders have been less exposed to outside influences?" So speculates Fan Ching-wen, formerly a researcher of musical anthropology at the Academia Sinica's Institute of Ethnology.

But in terms of the functions the songs fulfill, their use as a vehicle for storytelling is the same in both Papua New Guinea and among the Ami. For instance, Christopher Roberts says, the song Kwetalabogi is used as an expression of love, and is usually sung to the accompaniment of dancing. It was also the first song he played together with local aboriginals when he first arrived in Papua New Guinea. "When the stringed instruments started playing, I discovered that all the people there were musicians," says Christopher Roberts, describing the astonishment and wonder he felt at that time.

"One night

I was dreaming

As if you and I were together

All my mind goes just to you

Favorite one

Bright moon going down to the sea

Bright light alluring

So very quiet

While all the people are fast asleep

But suddenly I stand up from my dream

Realizing

My dreams are tricking me

All my mind goes just to you

Favorite one. . . ."

(Kwetalabogi-"One Night")

A hint of sadness?

Just as in Hualien County in Taiwan, the partners with whom Christopher Roberts researches the music of the Trobriand Islands are a musical ensemble made up of members of one extended family-the Komwa Komwa String Band.

The Komwa Komwa String Band was founded by an old man named Tobwaki. While in his middle age Tobwaki was trying to win the affections of a young woman from a neighboring village. But the girl never responded to his advances, so using his betel nut purse as a drum, Tobwaki made up and sang many "komwa komwa" ("truly inside") love songs to her. In this way, he finally won her heart. When word of Tobwaki's success spread, the young men of his village began to pester him to teach them the skill of composing this kind of song. Some of them got together with Tobwaki, and the Komwa Komwa String Band was born.

Komwa Komwa's songs on the Betel Nuts album more or less trace out the "musical history" of the band. For instance, they have often had the opportunity to leave their own island and go to sing on other islands in Papua New Guinea. While waiting to perform, at the dock when leaving, or when they got homesick, they made up many songs. Accompanied on guitars and Christopher Roberts' double bass these songs' melodies seem light and happy. The singers' voices express their emotions very directly, and their singing is very uninhibited.

By contrast, when listening to the Ami tribe songs, "could it be that because we are more familiar with our own tribes, we feel that 'Api and the others' singing has a hint of sadness about it?" wonders one listener.

For instance, the song Cikur An describes the feelings of Ami from Ciwidian while working for the Han Chinese at a logging camp at Cikur An (Fanshuliao) shortly after Taiwan's retrocession to Chinese rule.

In those days the highway along the coast of Hualien and Taitung counties had not yet been built, and to return from Cikur An to Ciwidian one had to cross several mountains, so getting home to see one's family was no easy matter. When the Ciwidian aboriginals had finished their day's work they would go back to the workers' dormitory hut in threes and fives, and there at night after the torches had been put out, they would sit in a large group, looking at each other and thinking of their girlfriends, and of how once they had worked long enough they would have the money to buy their girls presents. 'Mui and his companions composed this song to express those feelings. "This song is a reminder of our father's experiences, so as his sons we have to learn it," says 'Api.

"From the 1960s and 70s, economic development began to affect Hualien, and Ami tribal society began to be 'marginalized.' Songs such as this, which describe the emotional upheaval among tribespeople in a period of change, still preserve the typical rural color of Ami singing, but they also have acquired a touch of melancholy," says Wu Ming-yi, who teaches at Yu Shan Theological College in Hualien, and who has been studying the changes in Ami songs for many years. He adds that Cikur An is a typical example of this trend.

Another example is Miki Sabi'ay A Ma-tu---asay ("The Old Man in the Shade") which Huegu learned in Taitung County. The whole song is made up of a series of calls such as "Hey, hey, heng, hou!" Huegu says that as this song has no words, it has to be sung from the soul, to express the feelings of an old man who has toiled hard under the hot sun only to see his fields dried up and his plants withered by a drought. Different phrases of the tune go from very high to very low, making the song almost impossible to accompany on the guitar. When Huegu sings it in his deep, powerful voice, there is no need for explanation-everyone knows this is not a happy song.

A diary in song

Folk musicologist Ming Li-kuo says that of the Ami songs on the Betel Nuts album with which he is familiar, many are set to tunes which are so well known throughout the Ami villages that they are "as familiar to everyone as their own language." 'Mui and his family have simply put their own words to them.

Of course, the massive changes in tribal life have also brought some changes to Ami singing.

For instance, The Old Man in the Shade, which Huegu sings, is a southern Ami song which was popular in Taitung. "Originally it was a call-and-response song between a lead singer and chorus, which was the real distinctive style of Ami singing," says Ming Li-kuo-but Huegu leaves out the response sections.

Another example is Yo Pitatalaen ("The Place I Wait For You"). The old people usually sang this song in four verses full of images from nature such as the moon, the stars and the sound of the wind. "Only then was it really close to aboriginal life," says Wu Ming--yi. But in 'Api and the others' recording, they simplify it to leave only the section describing the sound of the wind. Thus Wu feels that Betel Nuts does not really do full justice to the heritage passed down by older singers.

Also, in terms of the changes in traditional Ami singing, most of the songs collected on the Betel Nuts album have been given set lyrics and are accompanied on the guitar. Thus although the tunes are still traditional ones, the songs have already absorbed many outside influences.

Who knows what is genuine?

"In the past it would have been very difficult to speak of the aboriginals singing 'a song,' because most often they had both call and response parts, and one song would lead straight into another. How long each song lasted was also very flexible," says Ming Li-kuo. In his view, 'Api and the others' singing continues in the tradition of the Japanese occupation and post-retrocession era, of taking a section out of one of the tunes used for singing at joyful gatherings. Thus what the Betel Nuts album "records" is the way Ami traditional music has changed in the modern era.

In past times Ami songs had no set lyrics, but could be adapted to suit any occasion. Thus they expressed the original spontaneous creativity in Ami culture. Today, the songs of 'Api and his companions still serve to strengthen emotional bonds within the group, but they have also gained an ever clearer descriptive function, becoming "songs" with tunes and lyrics that are more and more fixed. In terms of both expression and creativity, they are growing more like modern songs.

Ming Li-kuo believes this represents a very important change in the songs' cultural significance. He compares it to the changes in the Harvest Festival, in which the rituals were originally led by men, which for the Ami was a way of redressing the balance of power between the sexes in a matriarchal society. "Originally women were forbidden to take part in the Harvest Festival, but from the Japanese era on, women have been allowed in. Perhaps this is indicative of how the matriarchal social system has gradually been broken down, and the demarcation lines between men and women are no longer as clear as they once were," says Ming Li-kuo. The way Ami singing has been broken down into fixed individual "songs" shows how it too has been influenced by industrial civilization.

But 'Api and his companions, living in the here and now, are not worried about the "cultural significance" of what they are singing. Just to have the chance to sing, and to sing songs they themselves feel are "genuine," is terrific fun!

Christopher Roberts says that from his background of having studied Western classical music, he sees music like that of the Ami or the natives of Papua New Guinea as the only "real music"-music which comes from the forest, the sea shore and "from home." He finds them both equally unforgettable. Nonetheless, because of the two cultures' different stages of development, the music of the Trobriand Islands really does seem more "homespun" than that of Hualien.

On the Betel Nuts album, there is a Tro-briand Island song called Kauyanuba ("The Betel Nut Pouch of Memories"). Roberts says it is representative of a particular type of song from Papua New Guinea. Just like a betel nut pouch, the song is full of memories of the dead.

On the Trobriand Islands, the sun sets behind the island of Tuma, which is where the souls of the dead depart to. Kauyanuba describes a man who wants to see his dead girlfriend again, and who makes magic to speak with her. When he recites a spell, the fragrance of sweet basil flowers has a magical effect: during the night when everyone is asleep, he becomes a spirit, and can hear and reply to her words as she speaks from Tuma. In the spirit world, people become as they were in their youth.

"To the girl's words, the boy replies, their magic made through the aroma of the flowers. . . ," the voice of Trobriand Islander Toilegogula echoes from the CD.

Eternal time

Under a blue sky, as birds call and a mountain breeze brushes lightly across their faces, Huegu and Vala Udai's guitars begin to sound. Amid the paddy fields of their old home in Ciwidian, sitting on the ground, 'Api lifts his voice and again begins to sing. His voice is bright but tender, and full of rural color. To one side, Christopher Roberts, with his tousled brown hair, sets up the tape recorder and microphone, and presses down the keys.

"I await you here

Each of these nights

. . . waiting. . . ."

p.107

In a crowded cultural center in eastern downtown Taipei, the Betel Nuts raise their voices in song, bringing more city folk an understanding of Ami culture.

p.108

"I did it-I killed a wild boar in the mountains!" this Ami hunter of Ciwidian Village says excitedly. Such catches are said to have been rare in recent years.

p.109

The celebration gets under way. The boar meat is cooked, and drink follows drink just as song follows song. In the cold winter of Taiwan's east coast, such a gathering warms both the body and the heart.

p.110

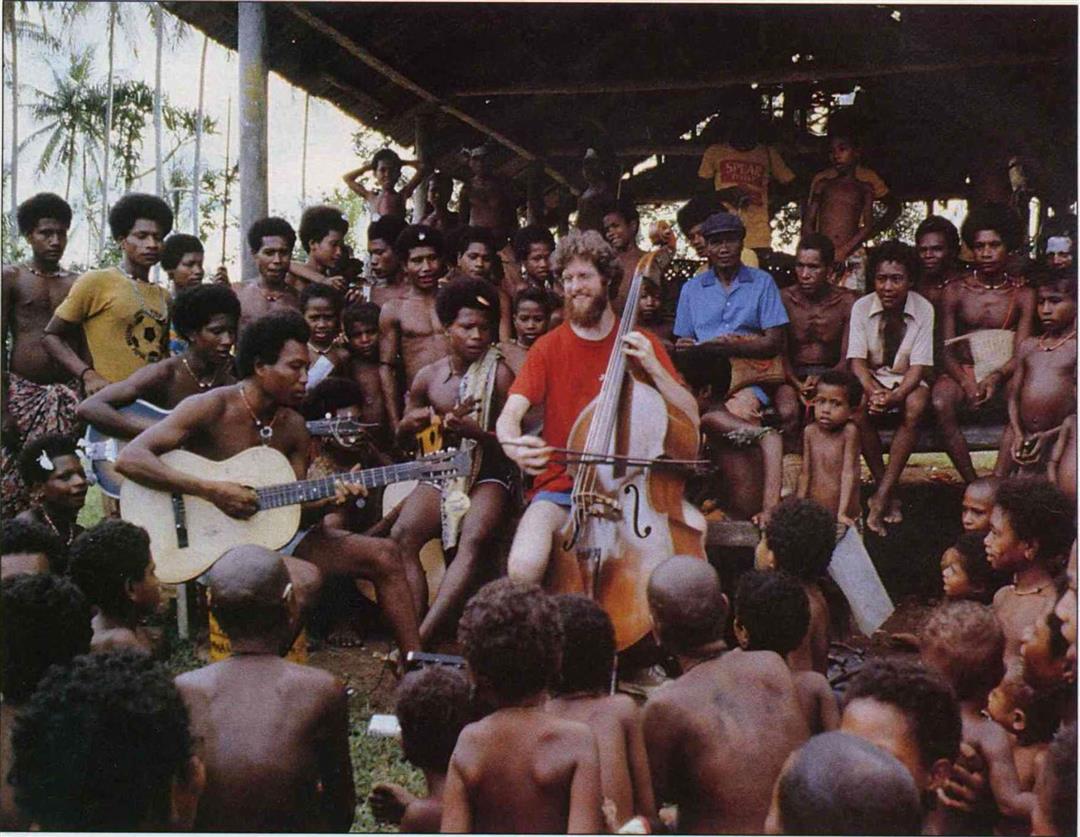

"As evening fell around us, fires were lit as many, many people gathered around my bass and very light rain touched our skin. Young men had ukuleles, and some guitars. I handed microphones to the children to hold as I assembled my flute, tuned up my bass and turned on the tape recorder." Thus writes Christopher Roberts, describing his experiences in Papua New Guinea. (courtesy of Trees Music and Art)

p.111

Traditional hand-held drums used by Trobriand Islanders when dancing.

(drawn by Christopher Roberts' mother, Patricia Hills)

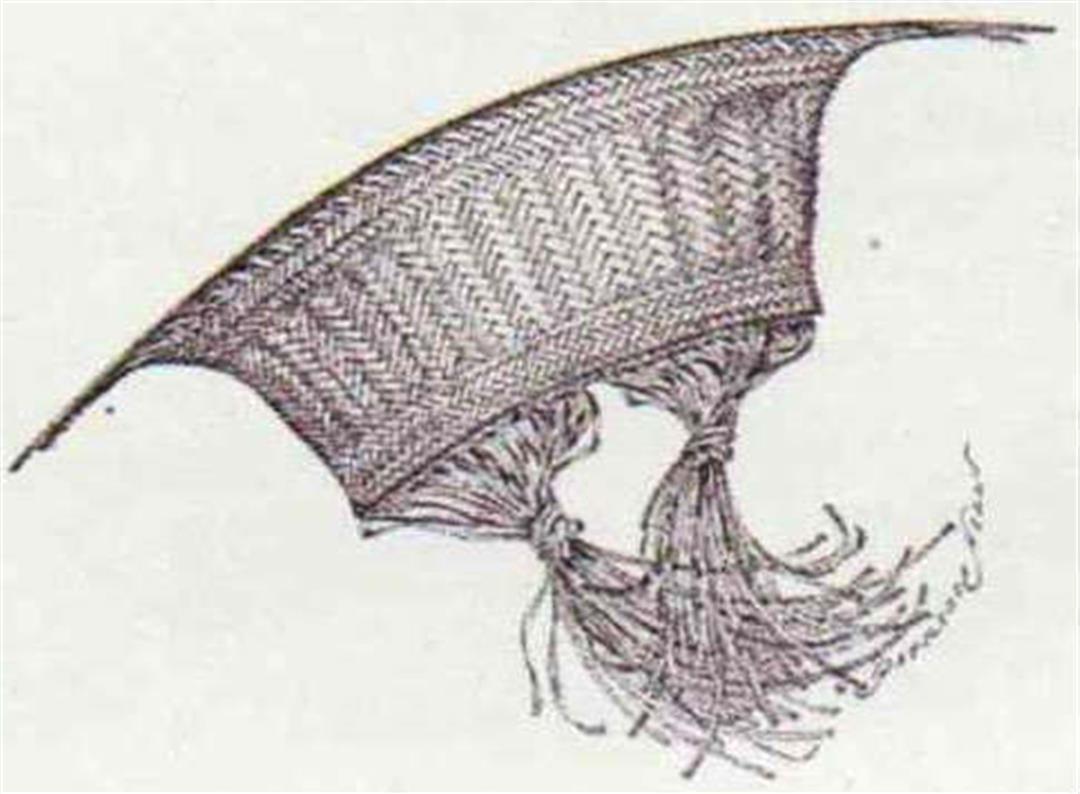

A betel nut purse from the Trobriand Islands, Papua New Guinea. (drawn by Patricia Hills)

For the Ami people, offering betel nuts is the first step in making friends.

p.112

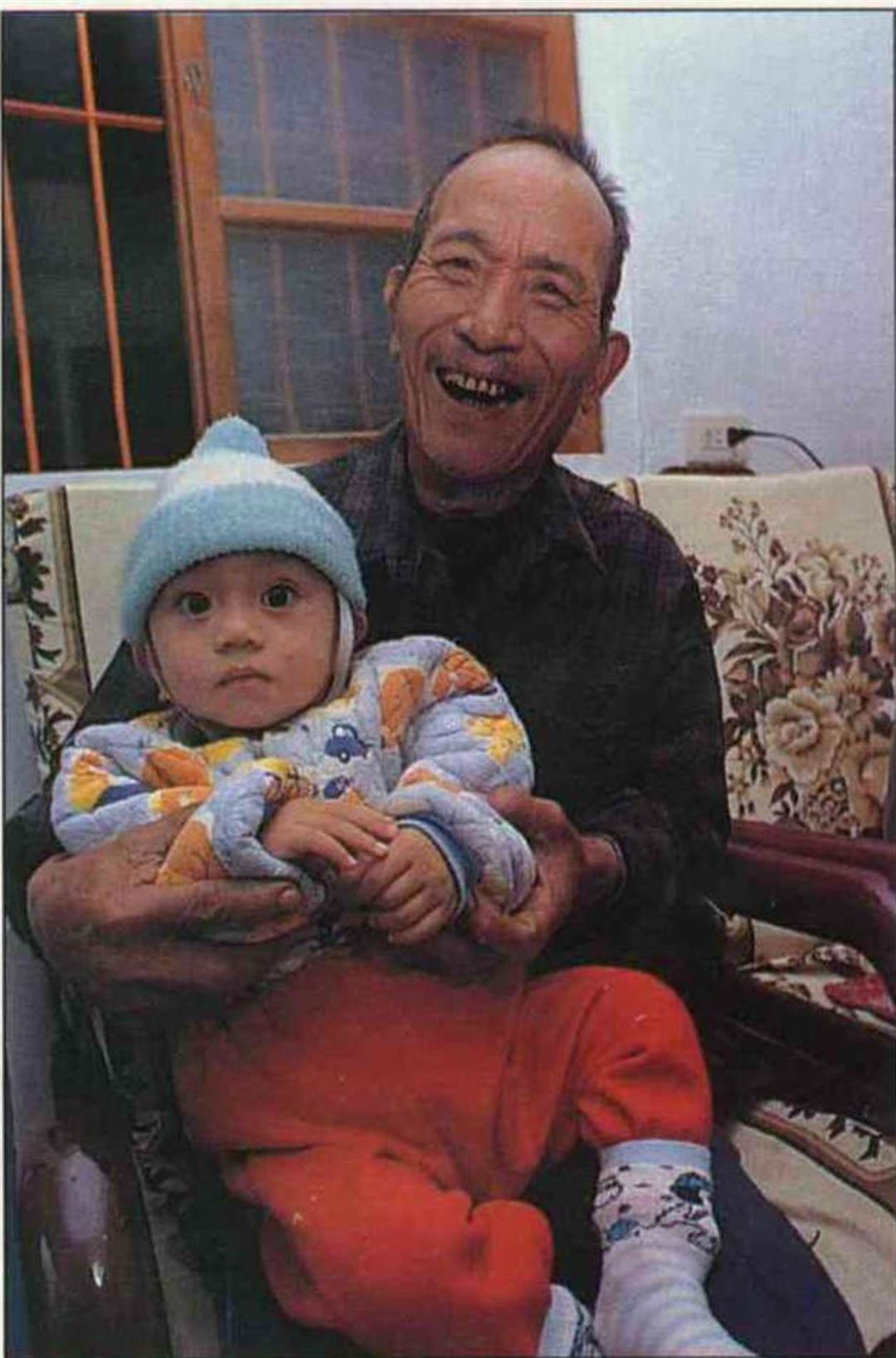

'Mui, an old chieftain of Ciwidian Village, is 'Api's father, and is also recognized as a fine lead singer in tribal singing.

p.113

When Christopher Roberts and the Betel Nuts travel around the Ami villages collecting music, they rely for transport entirely on this taxi, which is also Huegu's means of livelihood.

p.114

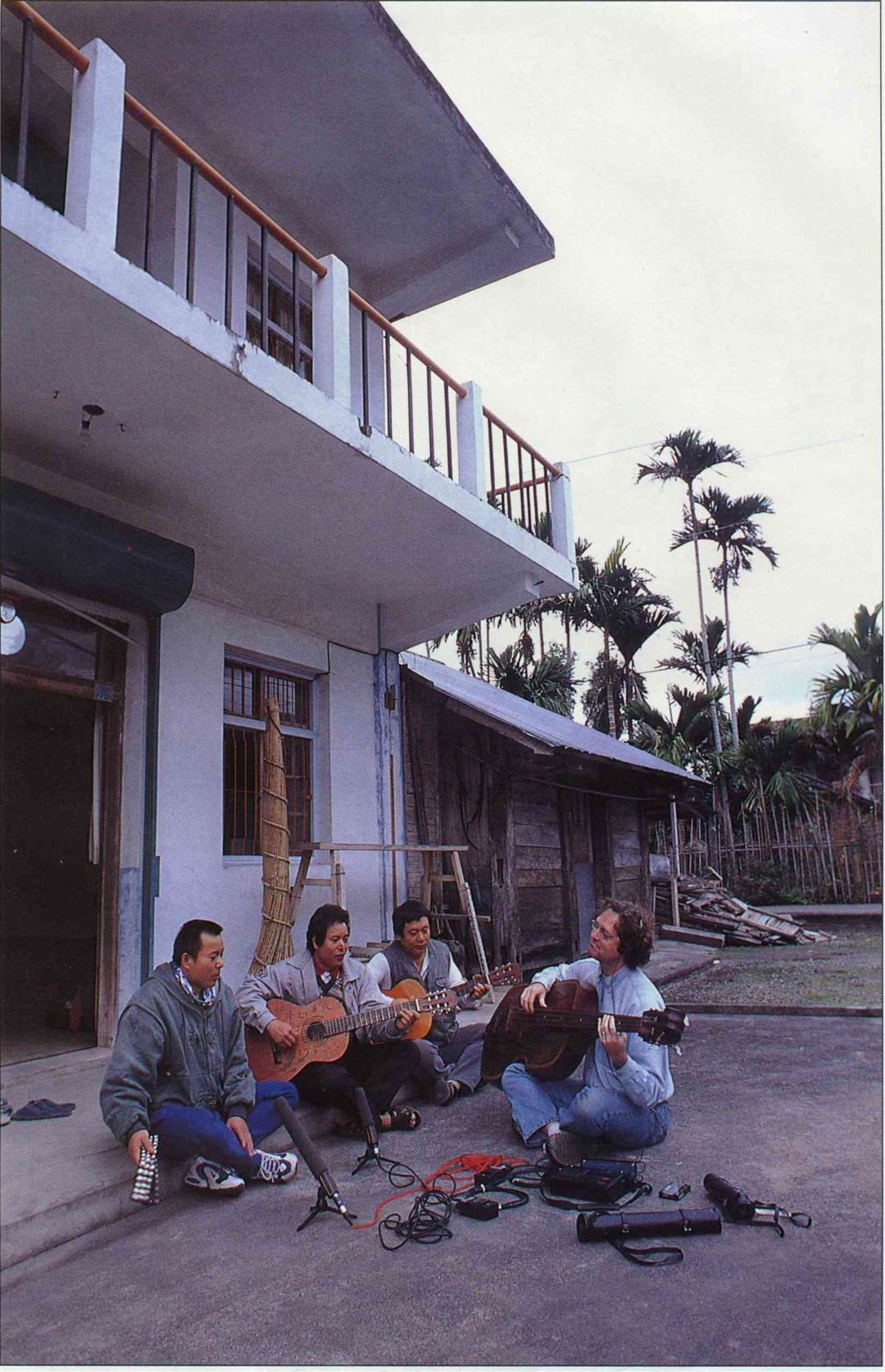

Many many songs have been recorded like this in the yard outside 'Api's old family home in Ciwidian.

"As evening fell around us, fires were lit as many, many people gathered around my bass and very light rain touched our skin. Young men had ukuleles, and some guitars. I handed microphones to the children to hold as I assembled my flute, tuned up my bass and turned on the tape recorder." Thus writes Christopher Roberts, describing his experiences in Papua New Guinea. (courtesy of Trees Music and Art)

Traditional hand-held drums used by Trobriand Islanders when dancing. (drawn by Christopher Roberts' mother, Patricia Hills)

A betel nut purse from the Trobriand Islands, Papua New Guinea. (drawn by Patricia Hills)

For the Ami people, offering betel nuts is the first step in making friends.

'Mui, an old chieftain of Ciwidian Village, is 'Api's father, and is also recognized as a fine lead singer in tribal singing.

When Christopher Roberts and the Betel Nuts travel around the Ami villages collecting music, they rely for transport entirely on this taxi, which is also Huegu's means of livelihood.

Many many songs have been recorded like this in the yard outside 'Api's old family home in Ciwidian.