Chinese global village

Reporters from Taiwan Panorama have traveled many times to report on Chinese immigrants in the United States, where there are more overseas compatriots than in any other country in the world.

In 1988 our reporters visited Angel Island, home to a former US immigration station that Chinese migrant workers passed through between 1910 and 1940 on their way to gold mining and other jobs. Some 175,000 Chinese spent extended detentions on this small island just north of San Francisco, and left verses carved in the walls that achingly expressed the pain of the experience: “Trapped on Angel Island / in search of a home / no future beckons / to the lost and forlorn....”

Some 400,000 ethnic Chinese immigrants entered the US in the 1970s, and then this number doubled to about 800,000 in the 1980s.

On a visit to “Little Taipei” in Flushing (part of the New York City borough of Queens), our reporters were able get by just fine in either Mandarin or Taiwanese, both of which were spoken in accents familiar to anyone from Taiwan. Then our reporters moved on to the largest Chinatown in the world, in Lower Manhattan. The signs of its long history were everywhere in evidence.

In the newer Chinatown communities of the US, one runs into a very different stratum of society, for many of the more recent transplants come from highly educated backgrounds. This has brought a big change in the image of Chinese immigrants. No longer are they automatically thought of as operators of restaurants and laundries.

South Africa

There is also a large Chinese community in South Africa, and as in the US there exists the same distinction between those who arrived long ago and those who’ve come more recently. While the financially strapped immigrants of an earlier time are mostly shopkeepers and restaurant proprietors, those who’ve come from Taiwan since the 1970s tend to be investors and businesspeople. All of a sudden, the labor-intensive operations that constituted sunset industries in Taiwan found a second wind as “sunrise industries” in South Africa, thanks to the low wages there.

Of course, we would be remiss in discussing Chinatowns if we failed to mention Yokohama, which is home to Japan’s biggest Chinatown, said to be the safest and most attractive Chinatown in all the world. Sun Yat-sen visited Japan 15 times while in exile after his first failed uprising, and on many of those occasions he stayed in Yokohama’s Chinatown.

In the 1990s, the Chinese community in Yokohama took advantage of a “China craze” to score big success in the restaurant business.

Investor immigrants

The 1980s saw a big wave of investor immigrants to New Zealand and Australia. The new generation of ethnic Chinese brought money, technical expertise, and business management experience with them. Indeed, it appears that the governments there may have been screening to get precisely this type of immigrant. Some left for foreign shores in search of better living conditions. Some did it for the sake of their children’s education.

In 1996, however, xenophobic distaste for Asian immigrants swept through these two countries. There was talk about a “resurgence of the Yellow Peril.” After a visit to New Zealand, our reporters made sure to let readers know that Chinese immigrants were the first to export New Zealand’s dairy products abroad, and even New Zealand’s kiwi fruit originated in China.

Taiwan Panorama returned to Australia in 2011 to visit the big Taiwanese community in Brisbane, and there we found that our compatriots had basically settled after a decade or two into one of three categories. Those who had struck it rich were very happy to hunker down permanently in Brisbane and enjoy a life of gardening, fishing, and golfing. A second group, however, had opted for the father to pursue a career in Taiwan while the mother and kids made lives for themselves down under. And a third group comprised those who were still struggling, but were nevertheless determined to stay for the long haul and somehow achieve success. In the meantime, a second generation of children born in Taiwan but raised in Australia find themselves—as bilinguals with a bicultural ease about them—even better equipped than their parents to shuttle back and forth between the northern and southern hemispheres and make their way in life.

They say that “only the hardiest among us dare cross the seas.” But, after the passage, what then? The Chinese diaspora is like a fistful of seeds, flung to the wind and carried to the far reaches of the earth. Wherever they set down roots, a totally new sort of hardy perennial grows and blooms.

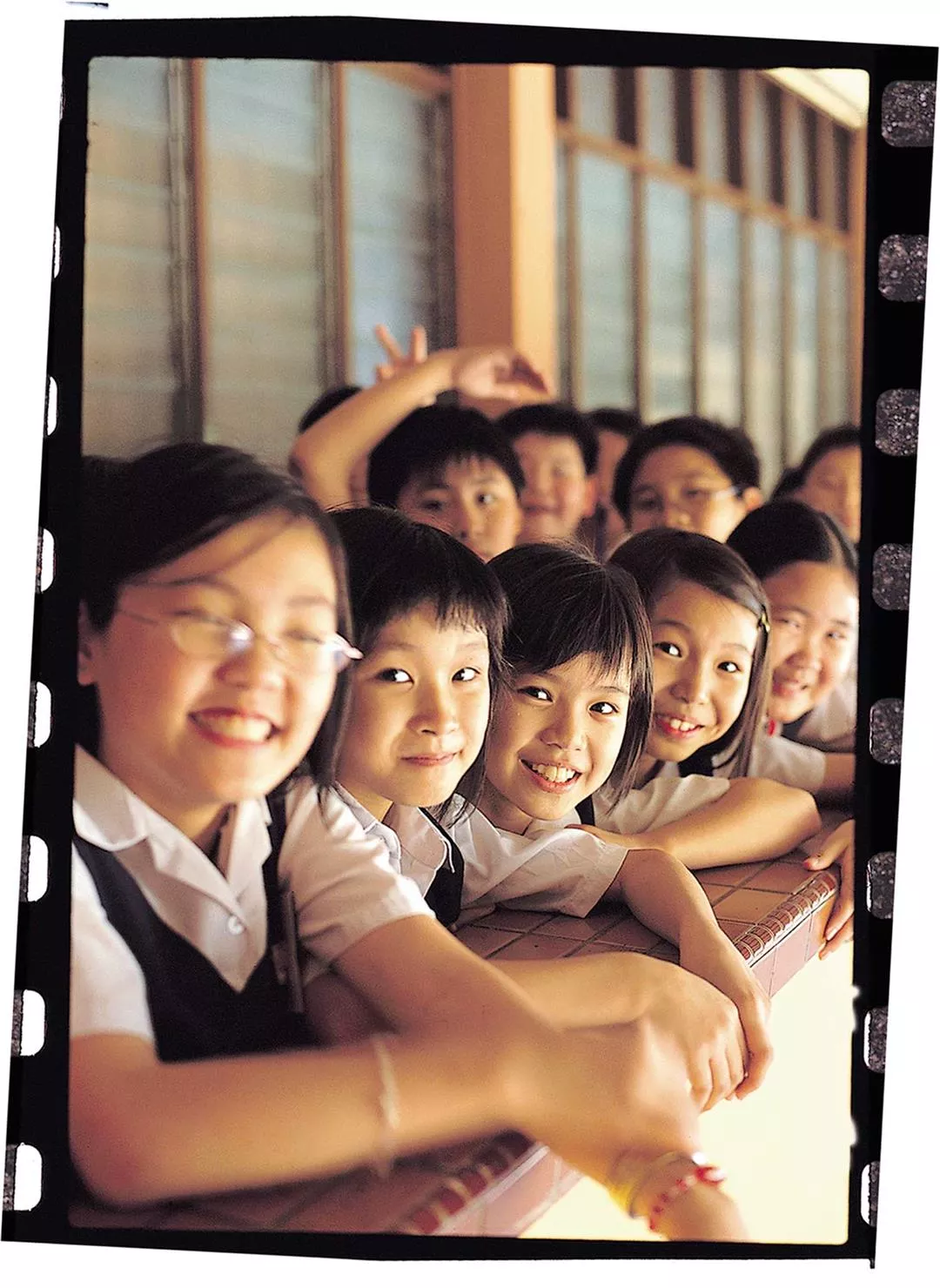

Chinese education is big in Malaysia, where there are more than 1,200 Chinese schools.

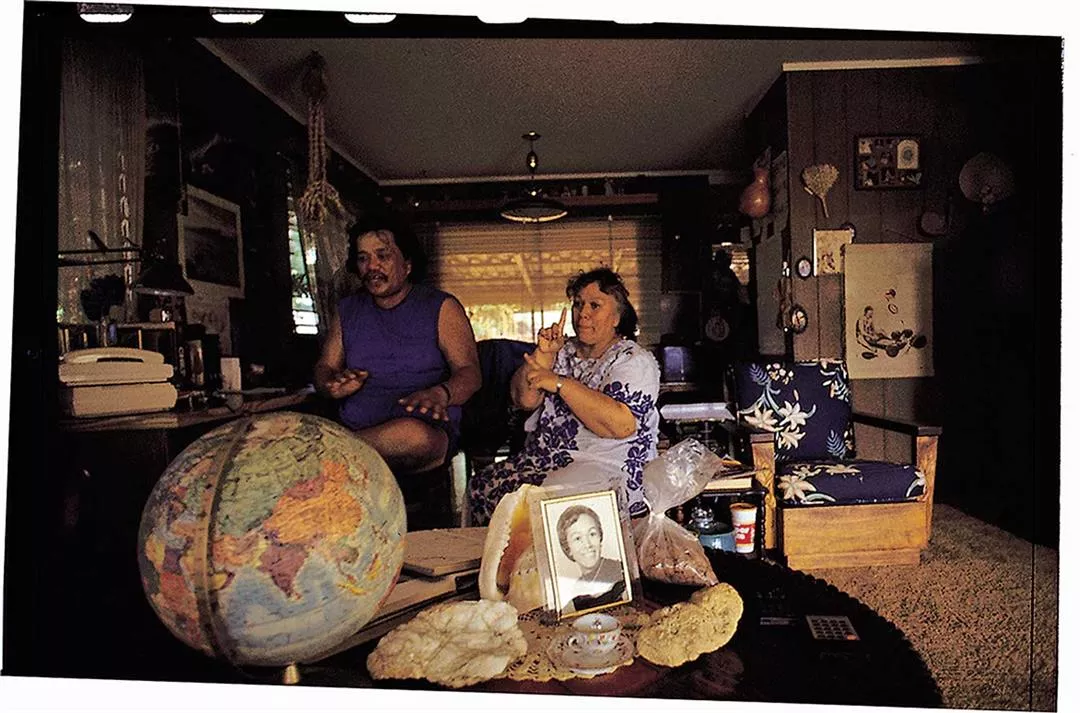

The Hawaiian mother shown here is one-quarter Chinese. She looks especially nice in the photo from her youth, sitting on the table.