The University of Chicago, like the great majority of other well-known private universities, was started up by men of the cloth, the behind-the-scenes backers in this case being the Baptist Church of America.

Curiously enough, one hundred years later, many University of Chicago students, religiously uninclined, have no idea of these Baptist ties, but consider the oil baron John D. Rockefeller the "school founder."

Calling him such would scarcely be going too far. The American Baptist Education Society began to solicit funds from Rockefeller to build a national Baptist university in the late 1880s, although views differed on where it should be located. In a runoff against Washington, D.C., Rockefeller picked Chicago and made a generous initial donation of US$600,000 to get things started. The university was born. Until his death in 1937, Rockefeller poured a grand total of US$35 million into the new university, a vast sum by any measure.

Freed from financial worries, the university went on to acquire up a 125-acre campus in south Chicago with a host of elegant Gothic-style buildings; and more importantly, it picked the right first president, who laid a firm foundation for the lofty academic position the university was soon to achieve.

The university's first president--William Rainey Harper--was not only one of the greatest educators in the United States during the past hundred years or so but an outstanding scholar in his own right, a professor of Semitic languages at Yale University who earned a doctorate there at the age of 18. When he was appointed president of the University of Chicago in 1891, he was just 35.

Brimming with youthful vigor and ambition, Dr. Harper came up with innovative plans for the future from the very beginning. Not content simply to have the new university founded and carrying out education, he set his long-term sights on building up graduate and professional schools for exploratory research, which was considered a rather experimental concept at the time.

All at one go he hired nine former presidents of other colleges, universities and divinity schools to come to Chicago to teach and manage university affairs. And he broke new ground by replacing the two-semester system with one of four quarters.

Anyone who has studied under the quarterly system in the U.S. knows how demanding its tight, compact ten-week courses can be. Yet according to the book A History of the University of Chicago, this kind of "terrifying educational experiment" earned broad affirmation among faculty and students alike.

The four-quarter system has a number of distinct advantages. As pointed out by the university's second president, Harry Pratt Judson, students can freely chose to enter or graduate at any quarter of the year without spending an extra six months or a year to make up a few needed credits. And when other schools go on summer vacation, the vast majority of the faculty and students remain on campus continuing to study and research during the summer quarter (from mid June to the end of August), which is just as important as the other three. The significance behind it all is the university's conviction that "academic research has no vacations."

The four-quarter system has now become fairly widespread in the U.S., adopted by such major universities as Stanford, UCLA and Ohio State.

Dr. Harper's contributions went yet further. At the time of its founding, he organized the university into five major divisions: the university proper; libraries, laboratories and museums; the university press; the university extension program; and university affiliations.

Viewed from today's perspective, these five divisions are common to many universities and nothing special to speak of. But in fact, the last three were Harper's very own creations. Some people say that the emergence of the University of Chicago sparked a series of reforms in the concepts of American higher education, and that is no exaggeration.

A university press, as its name suggests, is concerned chiefly with publishing the theses of its faculty and students and various academic works. Since the quality and quantity of its publications is one measure of how "diligent" a university is, university presses have become another arena of competition among universities themselves, indirectly stimulating the formation of a climate for scholarly research.

The University of Chicago Press, a trailblazer in the field, has been especially glorious in its publishing accomplishments, which include several classics of their kind. Two of its books, A Manual of Style and A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations, remain top sellers in the academic world: practically anyone who has written a scholarly article in the U.S. has referred to one or the other at some time.

The university extension program includes public lectures, evening classes, correspondence courses, continuing education and the like. A similar program had been promoted by Cambridge University in England, but Dr. Harper went even further by making it a regular part of the school's operations. He believed that the ultimate function of a university is to serve the public, and since many people are unable to enjoy a university education because of work, economic or other factors, enabling them to quench their thirst for knowledge through the university press, the university extension program and similar methods is an unshirkable responsibility.

As for affiliations, Dr. Harper in no way wanted to see the well-heeled new university stifle or overbear existing colleges in the Midwest but hoped rather to establish relations with them of equality and mutual benefit. Today the University of Chicago has faculty and student exchange programs with the Big Ten, Harvard, Yale and other institutions, along with agreements of cooperation with laboratories in countries around the world to provide students with further opportunities for enrichment and diversity.

The University of Chicago's vision and experimental spirit in educational thinking established its important place in U.S. educational history, and its position and contributions in academic research are likewise worthy of acclaim.

The university's educational system consists of three main parts: the undergraduate college; the four graduate divisions of biological sciences, humanities, physical sciences and social sciences; and the seven professional schools: the Graduate School of Business, the Divinity School, the Law School, the Graduate Library School, the Pritzker School of Medicine, the Graduate School of Public Policy Studies and the School of Social Services Administration.

Considered in closer detail, the University of Chicago boasts some "name departments" that have always ranked at the top of their disciplines, such as physics, economics, sociology (the department of social sciences, founded in 1892, was the first of its kind in the world), literary criticism, history and theology. To those in the know, mention of the term "Chicago School" immediately conjures up the image of some great scholar or revolutionary new theory.

Speaking of physics, the University of Chicago is renowned as the birthplace of atomic energy. On December 2, 1942, in the depths of World War Ⅱ, the first manmade nuclear chain reaction was successfully conducted there, laying the foundation for the birth of the atomic bomb two years later.

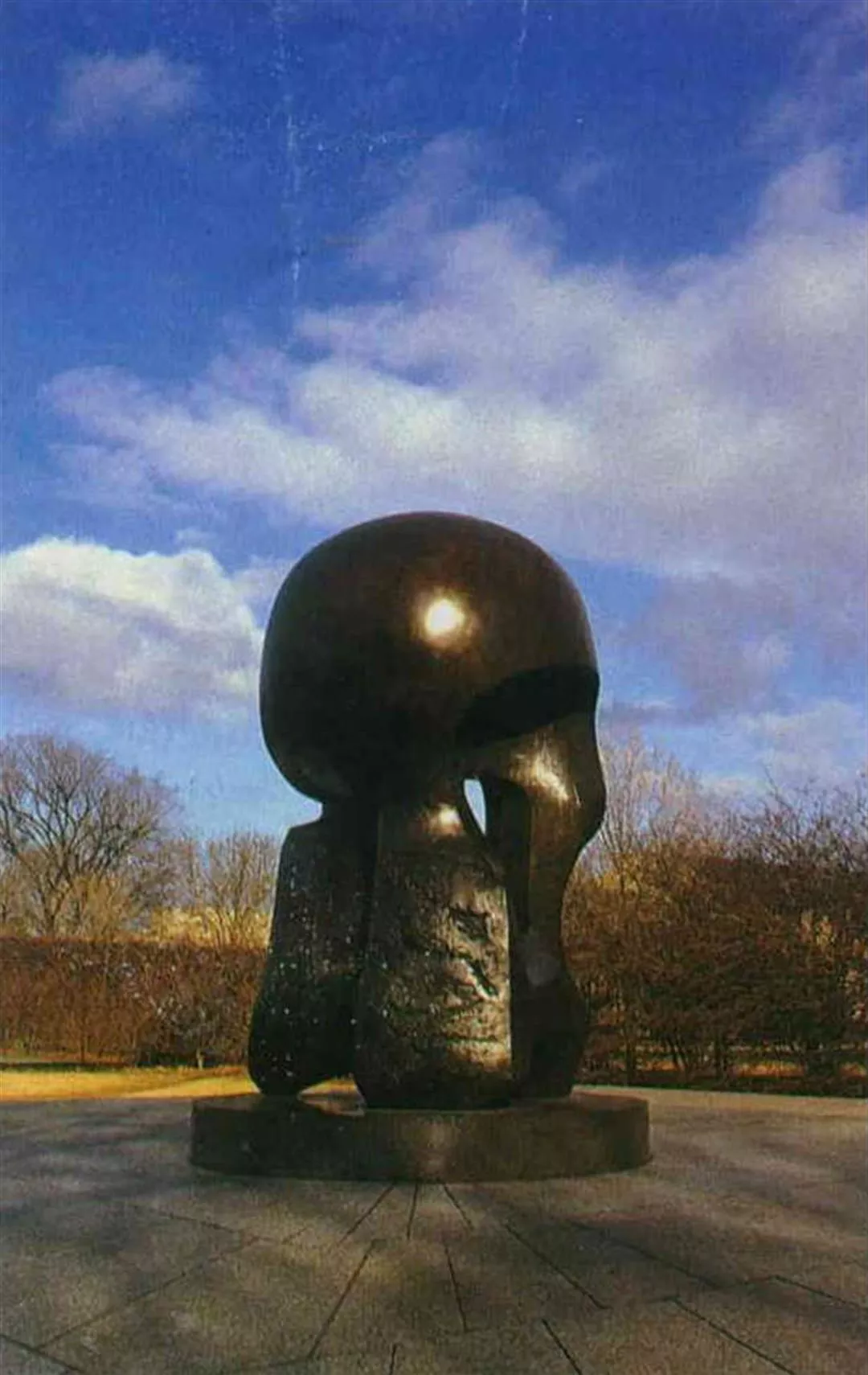

The story is still rather marvelous to relate. The scientist in charge of the project was the Italian physicist Enrico Fermi, who fled to the United States from the Fascists of Mussolini. He came to the University of Chicago in 1942, after three years at Columbia University, to teach and carry out experiments, little thinking that he would quickly succeed and thereby make the University of Chicago a focus of world attention. Not long after, the famous sculptor Henry Moore had a bronze statue called "Nuclear Energy" erected at the university, adding a lovely conclusion to the story.

The position of the University of Chicago in physics hasn't declined, and it achieved new heights in medicine recently when the country's first live liver transplant (an organ donated by a living person, often to a relative) was performed at the University of Chicago Medical Center last November. This pioneering step sparked a new lease on life for countless patients suffering from liver disease who have been unable to find replacement livers.

To understand more about the university's academic achievements, some startling figures can serve as evidence: during its short 100-year history, the students and faculty of the University of Chicago have produced 53 Nobel Prize winners (as of 1987), receiving this distinguished honor more than once every two years on average; and among the six categories of prizes (economics was started only in 1969), one recipient in 12 on average is from the University of Chicago.

The university's current staff includes six Nobel Prize winners and no fewer than ten who "very well could win next time around." It's small wonder that one of the best-selling items in the university bookstore is a T-shirt listing the names of the school's Nobel Prize winners.

The University of Chicago's high academic achievements are naturally related to the make-up of its student body. Entrance requirements to its undergraduate program, graduate schools and professional schools are strict, with a total ceiling of about 9,000 a year, and the fact that that fully two thirds are graduate students everywhere affects the school's research climate.

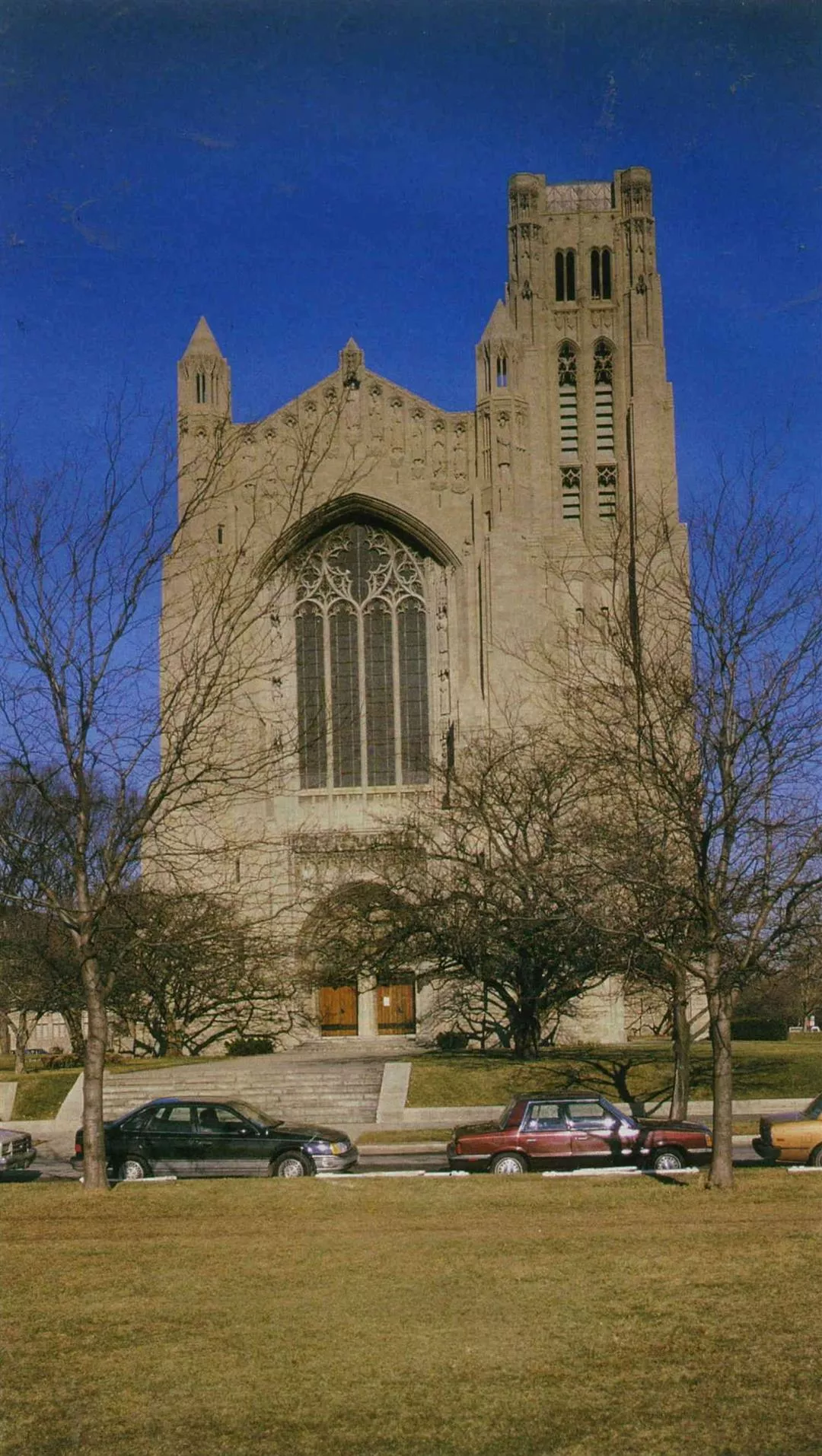

In fact, judging from its quadrangles of elegant Gothic-style buildings with their soaring spires and belltowers, one might speculate that the University of Chicago, the same as Harvard, Princeton and other noted private universities, aims at emulating Oxford and Cambridge in England in becoming a quiet and secluded grove of academia. Viewed in a certain aspect, the university has an air of detachment from worldly affairs, despite being located in the heart of the city.

Lin Hsiu-ling, who is studying for a doctorate in literature, describes her impression of the university with the phrases "medieval cloister" and "an ivory tower of academe heedless of the pursuit of fame and fortune in the world outside."

Financial pressure is another of the problems that students there most often face. Tuition at the University of Chicago is sky high: US$4,700 for three classes during a ten-week quarter, under normal circumstances without reductions, or more than US$18,000 for a full four quarters, which is right up there with the Ivy League elite. Perhaps because of complaints by parents at the size of tuitions, the U.S. Justice Department last year declared it was initiating an investigation into collusion and price fixing by privately owned colleges and universities, with Harvard and the University of Chicago prominently on the list.

Climate is another discouraging feature. The four- or five-month snowy season may not be considered long, but the cold waves that blow down from Lake Michigan are ruthless and Chicago is world famous for its blizzards.

"In the winter the temperature is low, the air pressure is low, and the students' feelings are even lower," Kuo Ch'ung-lun quips. Particularly in early January, when the winter quarter has just begun and students are back from spending a warm and cozy Christmas at home to face classes, blizzards, crime and financial worries, many of them have a hard time coping psychologically, and stories of students skipping class, seeing psychiatrists or attempting suicides are often heard of.

Describing the University of Chicago this way may seem a bit harrowing. Wang Chang-ling, who went to the U.S. as soon as she graduated from National Taiwan University and has relatives living in New York, it frank: she only knew that the University of Chicago had a famous reputation and a high academic position and never imagined that life there would be so "depressing." If you aren't determined to earn a doctorate of take the academic route as a career, the University of Chicago method of "hard study on a desert island" may not be worth it.

As for herself, if she were able to go back would she still make the same choice? Wang Chang-ling doesn't want to think about that kind of question. "I led a gregarious life at Taiwan University," she says, "but now that I'm at the University of Chicago I want to face myself in peace and quiet. . . ." Hard study on a desert island may be difficult all right, but if the academic ideals of the University of Chicago can be carried on that way, it accords with the common hope of the university's faculty and students and of the nation's entire academic community!

[Picture Caption]

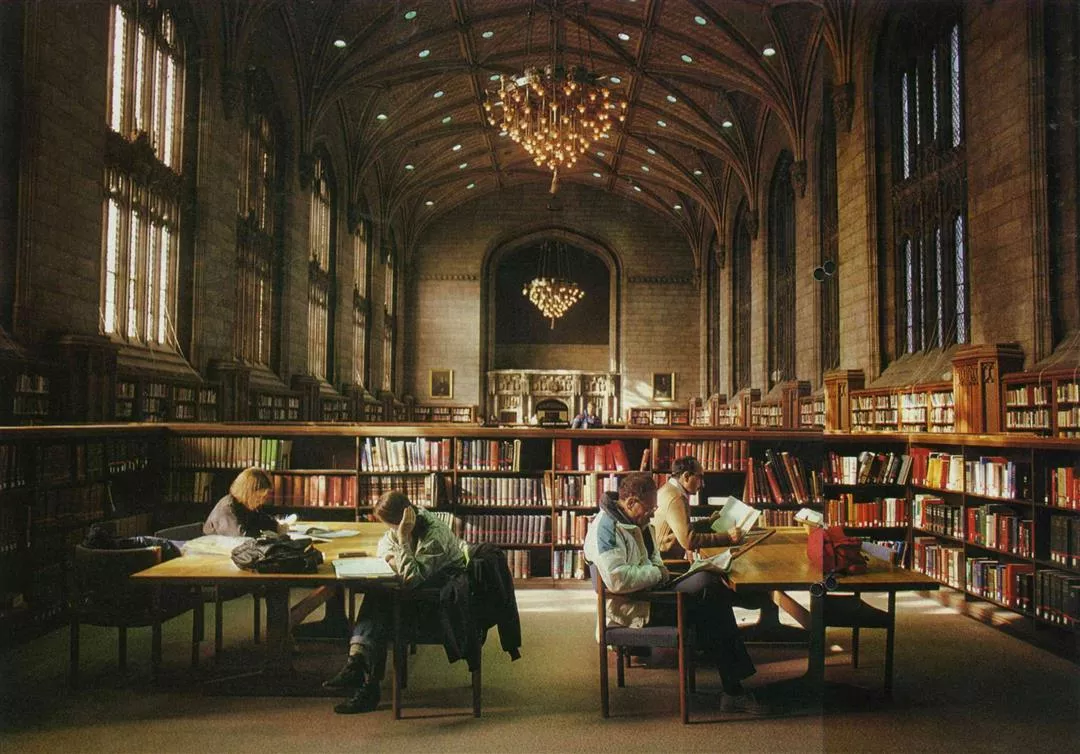

Studying is one of life's finer pleasures in refined and peaceful surroundings like these.

The colorful decoration that someone has put up over the library checkout counter to mark a friend's birthday adds a touch of interest to the day.

Robie House, a classic of modern architecture that is steeped in Oriental thought and integrates its architecture with the surroundings, is now the university's alumni house.

Students scurry around campus during the bleak winter months; they rarely dawdle.

A student's impertinent addition to this imaginative sculpture--a can of fruit drink--brings a smile.

(Below) This is the noted sculpture "Nuclear Energy" commemorating the revolutionary achievements of Enrico Fermi at the university.

The Rockefeller Memorial Chapel, renovation of which was completed only just last year, is the university's proudest building and the site of all its major ceremonies.

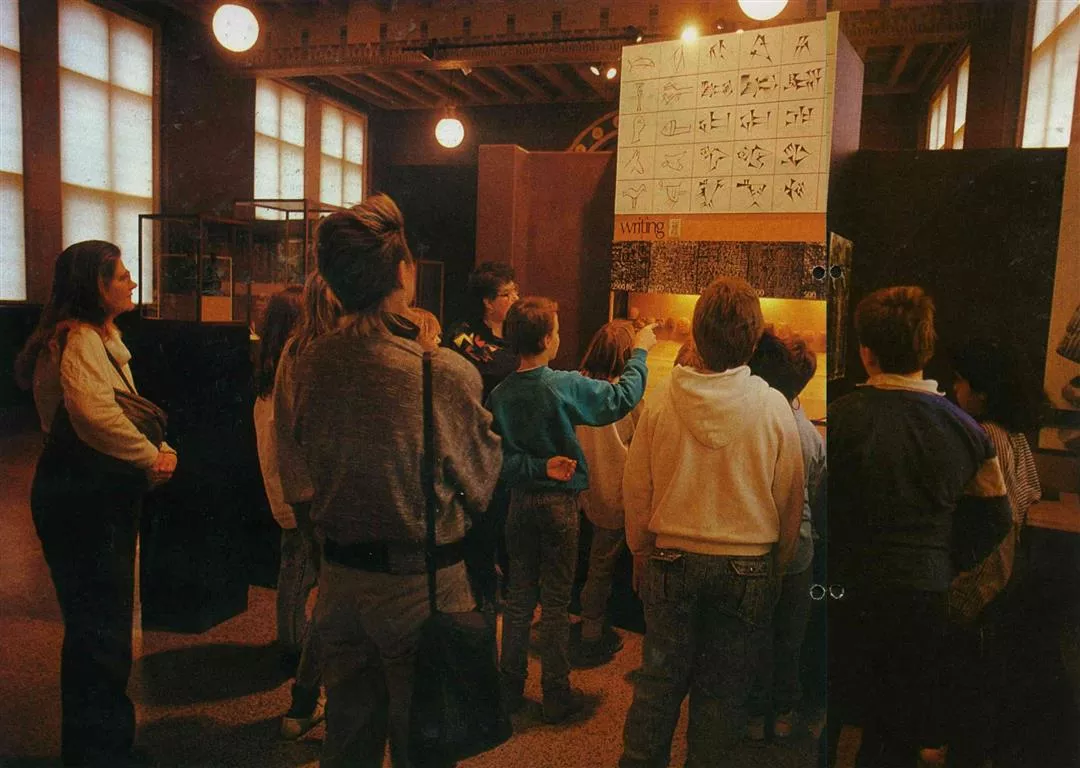

The Oriental Institute Museum, under the archeology department, is renowed for its collection of Near Eastern antiquities. Students and teachers from nearby schools often come for a visit.

The museum's holdings have been brought back from the Middle East over many years by students and faculty of the archeology department, who have made many astounding archeological discoveries.

Studying is one of life's finer pleasures in refined and peaceful surroundings like these.

The colorful decoration that someone has put up over the library checkout counter to mark a friend's birthday adds a touch of interest to the day.

Robie House, a classic of modern architecture that is steeped in Oriental thought and integrates its architecture with the surroundings, is now the university's alumni house.

Students scurry around campus during the bleak winter months; they rarely dawdle.

A student's impertinent addition to this imaginative sculpture--a can of fruit drink--brings a smile.

(Below) This is the noted sculpture "Nuclear Energy" commemorating the revolutionary achievements of Enrico Fermi at the university.

The Rockefeller Memorial Chapel, renovation of which was completed only just last year, is the university's proudest building and the site of all its major ceremonies.

The Oriental Institute Museum, under the archeology department, is renowed for its collection of Near Eastern antiquities. Students and teachers from nearby schools often come for a visit.

The museum's holdings have been brought back from the Middle East over many years by students and faculty of the archeology department, who have made many astounding archeological discoveries.