Charting an Era-Rock Records Celebrates Its 30th Anniversary

interview by Chang Meng-jui / photos courtesy of Rock Records / tr. by Scott Williams

February 2011

The world is filled with famous rocks, but only one has music in its soul. Taiwan's Rock Records has been a recording industry mover and shaker for 30 years.

Founded in 1981, the label has profoundly influenced Taiwan's pop music scene. It has also dominated the Chinese-language music market, creating Taiwanese-flavored hits that have been etching themselves into the minds of Chinese-speaking music fans the world over for the last 30 years. But the world's music industry has changed profoundly in the last decade, affected by new technologies and the growing popularity of online music. Even Rock hasn't been immune to the industry's troubles. Battered by the evolving technological terrain and afflicted with internal management troubles, Taiwan's iconic record label has been quietly losing its voice.

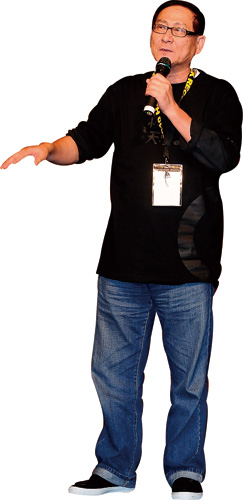

Rock chairman Johnny Duan says that just as Rock was shaped by the times, it is now being challenged by them. In an exclusive interview with Taiwan Panorama following the label's 30th anniversary concert, Duan described how his company got to where it is today. That interview follows:

Q: Rock Records is an iconic figure on the Taiwanese pop music scene. You once said, "Rock's fate was shaped by the times." What did you mean?

A: I often say that every step Rock Records has taken, from its birth and development to the present day, has been a surprise. Everything's happened by chance and been arranged by Fate. That's not modesty. If Rock records hadn't emerged when it did, I'd have been managing a small local record company. That Rock would be able to work with so many great singers and producers was totally unexpected.

At the most basic level, we were lucky. It was the times that gave us the opportunity to be a part of Taiwanese pop music. We founded Rock Records in 1981. Prior to that, my little brother Sam and I were publishing a rock-and-roll magazine that focused primarily on Western pop. We were listening to all kinds of American music, which we really loved, and naturally were also very interested in the recording business. The campus folk music movement was really taking off in Taiwan at the time, so we began to cover young folk singers, too. That's where we got the idea to set up our own label. All told, six of us invested in the company, including me, Sam, Wu Chu Chu, and Peng Kuo-hua.

(below, right) Active on the music scene for 13 years, Mayday believes that rock music can change the world. The album cover shows them at the start of their recording career.

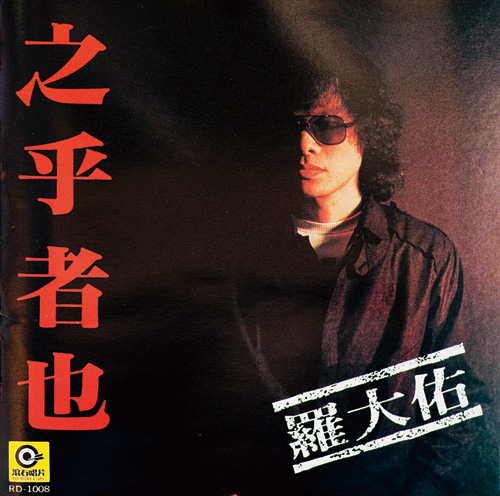

Our first record was a joint effort by Wu Chu Chu, Michelle Pan, and Lily Lee called Three Person Show that sold moderately well, but didn't earn much of anything. Then, in 1982, we released Luo Ta-you's Zhi Hu Zhe Ye, a mix of rock music and social commentary that earned great reviews and had excellent sales.

To tell the truth, at the outset, we had no idea what Rock would become because we didn't yet have any real understanding of the music business. We were just fooling around doing something we enjoyed. I still had a job, and at one point was feeling so worn out that I wanted to give up the business. Wu and Peng left Rock in August 1982, and established their own label: UFO Records.

Michelle Pan's Forever Blue Sky album, which also came out around this time, sold so well that we couldn't keep up with orders. We would spend all night packaging up records, practically living at the office, then rush out at dawn to deliver them. Sam and I finally quit our jobs in 1983 to focus entirely on Rock. Taiwan's economy was just beginning to take off, and it was a great time to start a business. We grabbed our chance.

But cassette tapes were the real key. The Japanese introduced the personal cassette player in 1979. Without the Walk-man, the world's music industry would never have made the money it did. The technology changed the way people listened to music. The hardware drove the software, spurring people to buy cassettes. As long as companies took their record-making seriously, every-thing they put out sold.

Q: You went from advertising and Western pop music to Mandopop. What were the key early records for you?

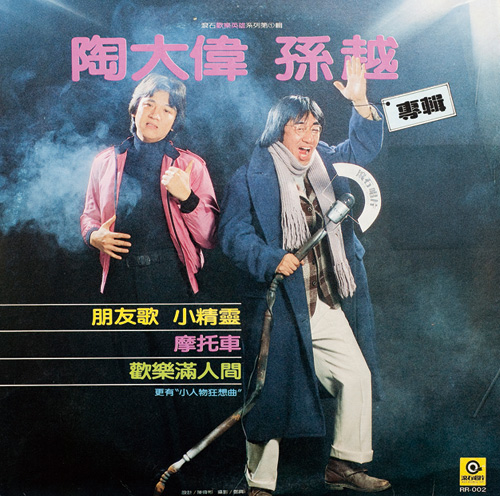

A: The first several albums Rock put out made the strongest impression on me and to me were most important. One album almost nobody nowadays has heard was David Tao Sr. and Sun Yueh's Friend's Songs. In those days, Tao and Sun were doing the very popular Little Guys on TTV. Then director Yu Kan-ping brought it to the big screen and asked Wu Chu Chu whether he was interested in doing the soundtrack. We'd been planning on talking to Tao and Sun, so having Yu approach us felt like divine intervention.

We took the tape to an ice-cream shop near the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall and put it on to see how the customers would respond. The shop ended up playing it for just one day. The employees told us that customers had complained that the tape was noisy and unpleasant to listen to. We brought it back with us to investigate and discovered that there was a problem: the tape hadn't been recorded to industry standards and the sound quality was poor. We rerecorded the material, incorporated some of the music from Pac-man, which was popular then, and even reshot the cover. When we released it, it sold 300,000 copies, and we were hearing Sun Yueh's line about "everybody together" all over town. CTV even used the music to open an educational program.

Our third key album was Luo Ta-you's Zhi Hu Zhe Ye. In those days, Luo was still practicing medicine. On hearing his raspy voice and angry delivery, a pop-music journalist predicted in the papers that the album would sell 2,000 copies at most. We weren't surprised by that, but told Luo that his music was the kind we wanted to make, no matter how many records it sold. In the end, Zhi Hu Zhe Ye blew away everyone in the industry by selling 700,000 copies.

Honestly, we really did have great confidence in Luo. I remember the media later describing the record as "a history-changing nuclear bomb thrown into Taiwan's Mandarin pop music scene."

Q: In its heyday, Rock set numerous sales records and was a uniquely large player in the Mandarin music scene. Was that because you had the best artists and producers? How did you get along with them?

A: Since its founding, Rock's approach has been to use planning to guide production. That is, we've come up with the ideas first, then had our producers implement them. It's different from the more traditional approach, where the producer takes the lead. Producers would first get songs together, then, once they had seven or eight, think about how to release them.

We didn't do that. Take Three Person Show, for example. We first came up with the idea of doing a record by three people who sang really well, tailoring songs to their particular strengths. Our producer then set the plan into motion.

We had faith in the people making our records, and remained hands-off while they were working on them. Luo Ta-you, Jonathan Lee, Wakin Chau, Johnny Chen, and Bobby Chen were all singer-songwriters, so of course we had conflicts. But they were "conceptual conflicts," focused on the matters at hand. We talked constantly and always found ways to resolve our creative differences.

I should also mention that while every-one noticed our successes, the fact is that we put out 1,200 records over the years, only about 100 of which people remember. What happened to the rest? The reason no one mentions them is that they flopped.

I remember doing our year-end accounting one year and discovering that only 16 of the more than 100 records we had put out had made money. And that was in Rock's golden age. A lot of people admired Rock's large stable of top producers and artists, and ask me how we got along with them. In fact, we didn't spend very much time with the artists and producers. We were business people. We provided a platform that allowed a lot of artists to express themselves. We welcomed every artist and producer. Those that made it, made it; those that failed, failed.

(first to third from left) Three records laid the foundations of Rock's success: Forever Blue Sky, Friend's Songs, and Zhi Hu Zhe Ye. Michelle Pan's deep, raspy voice, David Tao, Sr. and Sun Yueh's upbeat sound, and doctor-turned-singer Luo Ta-you's protest songs helped Rock's early efforts reverberate across the island.

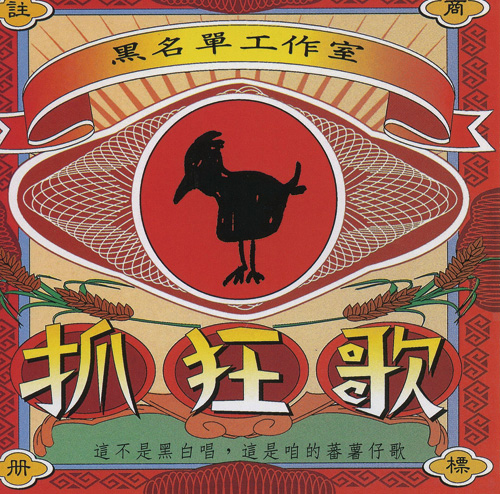

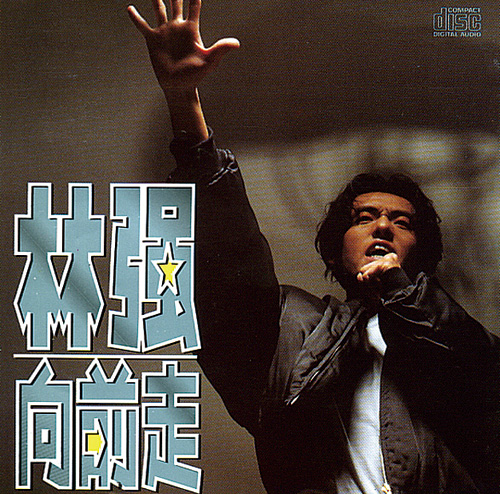

Q: Rock is also the "godfather" and an avid promoter of songs about the real world sung in Taiwanese. You even began the transformation of Taiwanese-language music by putting out albums such as Blacklist Studio's Songs of Madness, Lim Giong's Marching Forward, and Ju-tou-pi's Funny Rap I. At the time those albums came out, Taiwan hadn't long emerged from martial law. Moreover, you're a wai-sheng-ren [a Taiwanese born in mainland China, or descended from post-1949 emigres from mainland -China] to boot. Did putting out Taiwanese-language records have any special significance for you?

A: Though I'm a waishengren, I grew up with Taiwanese kids and don't have any problem identifying with Taiwan. My family moved from Hua-lien to Tai-chung when I was in the 11th grade. The Vietnam War in full swing, and Tai-chung's Qing-quan-gang Airport was serving as a supply and R&R base for the US military.

This was when rock music was really taking off in the US. Anti-war and anti-authority pop songs were everywhere, advocating human equality. And the counterculture movement was sweeping across the US. I completely immersed myself in this anti-authority music, totally identified with it. I'm anti-authoritarian to begin with, contrary to the bone. I saw putting out Taiwanese-language songs as a kind of anti-authoritarian act.

Meanwhile, Rock was attempting to become a more comprehensive record company. That meant we couldn't just put out Mandarin records. So we set out to release Taiwanese-language, Hakka, and Aboriginal music as well.

Rock kicked off the "New Taiwanese Language Movement" in the early 1990s with albums like Songs of Madness and artists like Chen Ming-chang, Lim Giong, and Wu Bai. At first, few people accepted the idea that Taiwanese-language music could address sensitive subjects and be socially critical. But these songs made an impact the moment you heard them. They reminded you of your connection to Taiwan. Some people said that Rock's New Taiwanese Language Movement shattered the stereotypes of Taiwanese pop music. I think that's spot on.

(right) "Rock was shaped by the times," says Rock chairman Johnny Duan. Defying present-day naysayers, he argues that Rock will continue to produce great music long into the future.

Q: In the mid-1990s, the international recording conglomerates came to Taiwan and bought the local UFO label. They also approached Rock. Why did you turn them down?

A: We had so many opportunities to sell Rock after the Big Five came to Taiwan. Why did we insist on remaining independent? Because too many Taiwanese music lovers told us: "You can't sell Rock!" One financial services company estimated that we could get US$210 million for Rock. A lot of people urged us to sell while Rock was at its peak, then start a new record company after the five-year non-compete agreement expired.

Rock was a strong, well organized company. It was like our own child. How could we bear to sell something we'd created with our own hands? I didn't feel like I was refusing a seductive offer. In fact, a number of companies approached us later about buying Rock. We talked to them, but could never come to terms. It wasn't just a matter of money; it was also about the huge differences in our thinking.

Q: Were the Internet and MP3s responsible for Rock's decline? Rock has seen the talent that used to come knocking at its doors choose to remain independent. Has the company also suffered from an interruption in the flow of artists?

A: Both are true. There's a cause and effect relationship there. Rock came along at the right moment in time and was built by that moment. We became the label that people said represented the music of the times. Technology-the cassette tape-made Rock a success. The cassette tape cast the die for the record companies, and brought us our moment in the sun.

Now we're dealing with the MP3 technology problem. Nowadays, rec-ords sell badly no matter how hard you work. Everybody just goes online to get them. We've continued to suffer heavy losses even though the digital music market has matured and users have become more accustomed to paying for music downloads. Our online revenues just don't come close to covering the losses from illegal downloads.

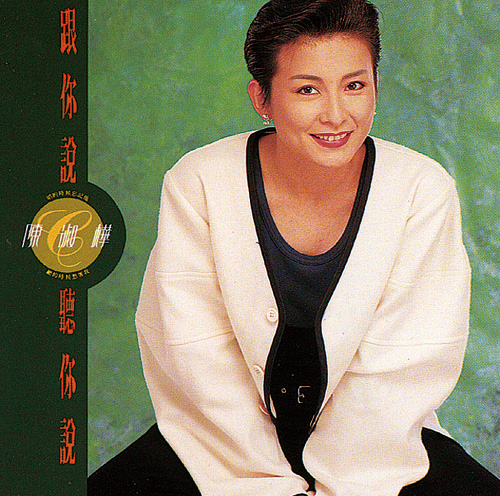

(second and first from right) With producer Jonathan Lee at the helm, Rock's 1990 release Talk to You and Listen to You turned Sarah Chen into a spokesperson for the young women living in urban Taiwan. The record also became Taiwan's first-ever million seller. You Make Me Happy and Sad, a 1991 Rock release, was one of Wakin Chau's most important albums.

As a result of this situation, labels have lost interest in investing and have little patience for developing new talent. The industry has been startlingly quiet. How do you draw talented people into an industry that's at such a low ebb? The folks with talent are either going into the game industry or getting into another field entirely.

The role of the record companies has changed since the rise of the Internet. The labels used to have money and were willing to spend it on music videos and ads that raised the profile of their artists. They also had distribution channels that gave the whole island access to new releases within a day. Record labels had resources and a willingness to invest. It was a high-risk, high-return industry. Everything changed with the emergence of the Internet. It allowed young people to write songs, produce their tracks, and sell their rec-ords online, all at little cost. The record companies lost importance. It used to be that being big helped when you were putting out records. Nowadays, size doesn't matter. Anyone with talent can set up their own studio. Mayday is a case in point. The changes in the business model have encouraged everyone to go independent.

Q: Rock has long been bringing mainland Chinese singers to Taiwan. Does the mainland offer a way forward for Mandarin pop? Does Taiwan retain any competitive advantages?

A: In 1990, Rock set itself the goal of growing from a purely Taiwanese label into a pan-Asian one by the year 2000. Why?

Because the mainland was liberalizing and its market was huge. If Rock was to grow large enough to compete with the international labels, we had to work with the mainland. The mainland had the market, and Rock had the products [in addition to its own products, Rock had licenses to distribute outstanding music from more than 200 independent foreign labels]. In other words, Rock was well positioned and felt that cross-strait cooperation would grow the Mandarin pop market.

Music is a content industry. Taiwan and China share a language, but differ culturally. It's no easy task getting a really good handle on that market. Moreover, the mainland treats pop music as a cultural industry, which means dealing with stringent controls. The mainland spends an enormous amount of time going through the motions on copyright issues, but its efforts aren't very effective. That makes working with the mainland an exhausting process. But as tough as it is, we have to do it. In any case, what business doesn't take a lot of work to get going?

We have always stressed that Rock is a provider of content. The mainland has a huge market, and we're getting used to working with one another. At this point, all Rock can do is continue to produce good songs and good music.

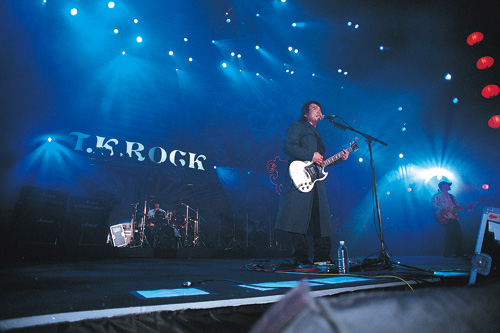

Rock's anniversary concert was a star-studded affair that saw artists such as Mayday, Alex Tu, Johnny Chen and Richie Ren mingling offstage with enthusiastic fans.

(below, right) Active on the music scene for 13 years, Mayday believes that rock music can change the world. The album cover shows them at the start of their recording career.

With the lifting of martial law, Rock's desire to challenge the traditional music scene intensified, and it began releasing Taiwanese-language albums about contemporary Taiwan. Key albums included Songs of Madness and Marching Forward. And the sight of Wu Bai, a Rock artist, dressed in black singing Taiwanese-style love songs was truly something new.

(second and first from right) With producer Jonathan Lee at the helm, Rock's 1990 release Talk to You and Listen to You turned Sarah Chen into a spokesperson for the young women living in urban Taiwan. The record also became Taiwan's first-ever million seller. You Make Me Happy and Sad, a 1991 Rock release, was one of Wakin Chau's most important albums.

(first to third from left) Three records laid the foundations of Rock's success: Forever Blue Sky, Friend's Songs, and Zhi Hu Zhe Ye. Michelle Pan's deep, raspy voice, David Tao, Sr. and Sun Yueh's upbeat sound, and doctor-turned-singer Luo Ta-you's protest songs helped Rock's early efforts reverberate across the island.

To celebrate Rock Records' 30th anniversary, dozens of artists, including Bobby Chen, Mayday, Wu Bai, and Wakin Chau, performed for fans at the Taipei Arena.

(below, right) Active on the music scene for 13 years, Mayday believes that rock music can change the world. The album cover shows them at the start of their recording career.

(first to third from left) Three records laid the foundations of Rock's success: Forever Blue Sky, Friend's Songs, and Zhi Hu Zhe Ye. Michelle Pan's deep, raspy voice, David Tao, Sr. and Sun Yueh's upbeat sound, and doctor-turned-singer Luo Ta-you's protest songs helped Rock's early efforts reverberate across the island.