Points and paths of low resistance

"This research began with the discovery of the 'bioenergy' of the human body," says Julia Tsuei, who heads the Clinic for East-West Medicine in addition to her responsibilities with the Foundation for East-West Medicine. Tsuei says that modern science has already confirmed that every living being contains electrical charges within its body. The human body is no different. Modern physiology shows us that although these charges are very small, we can nonetheless measure their strength and distribution. In fact, a number of modern medical devices, including the electrocardiogram, electroencephalogram, electromyogram and nuclear magnetic resonance imaging, all rely on the distribution of electromagnetic charges in the body in order to function.

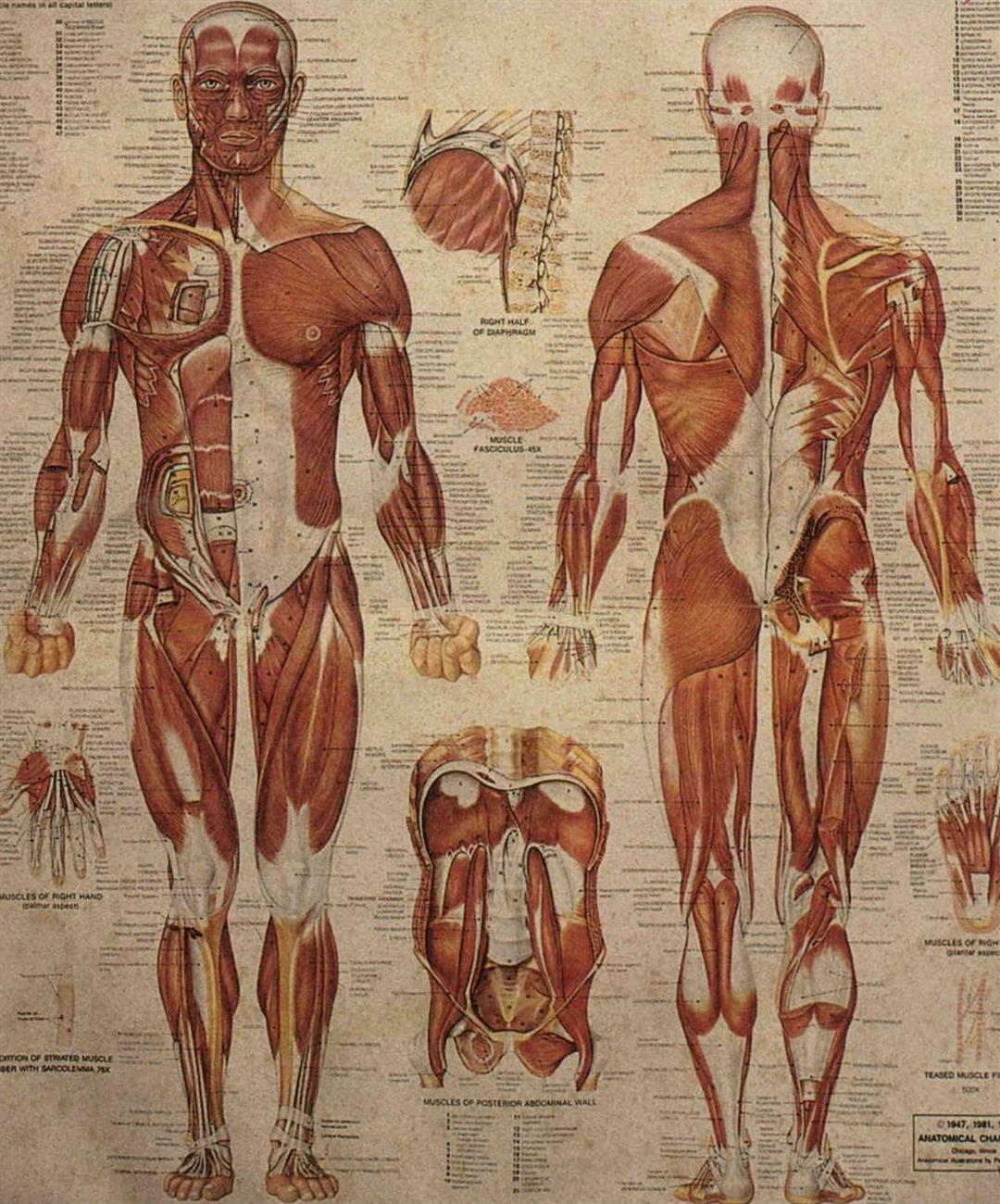

In the West, it was a German, Dr. Rein-hold Voll, who was the first to systematically record the electrical energy of the human body. Voll used an electrical probe to measure electrical resistance at points all over the body. He discovered that there were numerous locations which gave unusual readings, that is, which had lower electrical resistance, and that the distribution of these points delineated several fixed routes.

At the same time Voll was carrying out his research, a Japanese doctor named Nakatani was using an electrical device to test patients. Nakatani also discovered numerous points of low electrical resistance which he connected into pathways.

"The electrical pathways these two men discovered are in almost complete accord with the meridians of traditional Chinese medicine. Moreover, the points of low electrical resistance exactly correspond to the acupuncture points of traditional medicine," says Tsuei. In the 1970s, Tsuei herself became interested in traditional Chinese medicine and began researching acupuncture. This sparked her research into the meridian system and Voll's electrical probes.

From 1970 to 1979, Tsuei traveled frequently between the US and Taiwan promoting acupuncture. She also introduced Voll's device to the staff at the Traditional Medicine Research Center at Veterans General Hospital. She and Chung Chieh, the center's director, refined the machine, incorporating a computer and adding more functions. They called their device the "Qin Value Detector" after a unit of measure of chi, the "qin," defined by Chung. Chung felt that this device marked a huge advance in the integration of Western and Chinese medicine, and to commemorate this chose to name it after the Qin dynasty, the first to unify China. Although there are now other devices on the market, all are designed on the same premises.

"In fact, no matter what the researcher calls this kind of machine, all measure the resistance to a small amount of DC current run from probes on the skin through meridians associated with particular organs. The results are used to make a diagnosis. For this reason, all machines of this type are known as Electrodermal Screening Devices," says Tsuei.

Western medicine prioritizes anatomy and physiology and seeks clear physical evidence. It has a difficult time with the "invisible" meridian system.