Images come into focus on a screen.

At first you see only the clear blue Mediterranean, ringed by the peninsulas of Italy, Greece, Turkey, and Spain. The rest of the map is enveloped in shadow.

This region may well be familiar.

The shadows withdraw a bit, and parts of Hungary, Yugoslavia, the Near East, and Egypt come into view.

These places may not be so well known to you.

The clear blue sea has vanished. On the screen is a vast stretch of brown and yellow: the land of China.

Here you may be totally in the dark.

It was during the Enlightenment that European scholars first directed their attention to lands beyond the Urals and the Bosporus, and it was then that Europeans began to acquaint themselves with the distant, exotic world of the Orient, which had been cut off from them for so long by barriers of land and sea.

Before then, Marco Polo's account of his travels to the East, exaggerated already, had been embellished since with fantastic illustrations that gave free rein to the imagination of a curious public (See picture 1).

Marco Polo had described the Chinese imperial palace as being as large as a city, which was actually almost true. But in the hands of illustrators, the "City-Sized Imperial Palace of China" was practically a copy of a medieval castle in Europe (picture 2).

A so-called "Chinese princess" is clearly modeled on an aristocratic lady of the West (picture 3).

In the seventeenth century Western officials and merchants began traveling to China in person. One look may be worth a thousand words, but the pictures they brought back with them were still riddled with oversights. See, for instance, the "Chinese banquet" (picture 4) depicted by a Dutch consular officer. The dragon-wound pillars towering on either side, the scores of officials kneeling on the floor, and the pervading atmosphere of ceremony and ritual are accurately conveyed . . . but having forgotten to look up, he had to make do with a Western-style substitute for a ceiling.

Then consider the etching of a county magistrate judging criminals (picture 5). The terrified expressions of the prisoners, their handcuffs, leg irons, and cangues are all convincingly portrayed. But look at the magistrate's right hand: he's holding the brush in an impossibly awkward manner.

The Europeans were not alone in their fanciful ideas of distant lands. During ancient and medieval times, Westerners peopled the Orient with a host of fabulous creatures, including the single-footed sciapodes (picture 6), people with ears as large as winnowing fans (picture 7), and "men whose heads do grow beneath their shoulders" (picture 8). Bizarre, aren't they? But just look at the long-eared gentleman (picture 9) and the headless immortal (picture 10) pictured in the Shan-hai ching, or Classic of Mountains and Seas--don't they look like identical twins of their Western counterparts?

Mysterious, distant China: Just what kind of culture did it produce? Curious to know more? The Institute of Sinology at the University of Leiden has put together a series of some 20,000 color slides that vividly bring to life the culture of ancient China.

The project, aimed at Westerners who have had no previous training in Chinese studies, is called the "Visual Presentation of Chinese Culture." Dr. Erik Zucher, head of the Sinology Institute and director of the project, says that his initiation into Chinese studies as an undergraduate was a matter of plodding his way through ancient texts word by word. The most modern pedagogical tool they had at the time was a gramophone with a wooden needle that played sound disks telling "very bad stories in an unclear voice."

The teaching methodologies of his generation were a far cry from today's. Nor did they enjoy the firsthand experience of the previous generation of "China hands," many of whom had served in the country for years as diplomats or officials and whose enthusiasm for the humanist ideals they had encountered motivated them to pursue an otherwise neglected and esoteric field.

When he first read a translation of Lao-tzu as a student, Professor N.G.D. Margvist of Stockholm University decided to give up Latin and Greek and transfer to Stockholm University to study Chinese. Because he was afraid to tell his parents of what he had done and housing was hard to find, he slept in parks and train stations his first two months there.

When Professor Zucher decided to study Chinese, his classmates exclaimed, "Are you crazy? What do you want to study that for? What kind of a job can you find?"

Now both men have become world-renowned figures in their field, and the number of new students enrolling in their departments has increased over the years from a handful to hundreds.

An attraction to the culture of ancient China combined with the pull of the market-place are two prime reasons for the steady increase in new students signing up for China studies. Unfortunately about half of them always seem to drop out by the second year.

"Most of the new students are highly enthusiastic," Professor Zucher says, but once they get started they find out that learning another language and culture is an arduous process. And Chinese, after all, is very different from the German, English, and French that most Western students are familiar with.

Wilt Idema, another professor in the Sinology Institute at Leiden, explains that students are thrilled at learning their first ten Chinese characters and are still excited after learning a hundred, but when it comes to the 9,900 or so left, it's hard for anyone not to find it a bit tedious!

Also, eighteen- or nineteen-year-olds find repeating sentences like "I want to buy two ten-cent stamps. I'm sorry, we only sell twenty-cent stamps" less than adequate to satisfy the intellectual ambitions they harbor just after entering college.

"Actually, not every student has the ability to accept a culture with a completely different language system and way of thinking," Professor Idema says. Students don't have to "become" Chinese, he feels, but at least they have to figure out a way to maintain their interest and motivation so they can acquire the necessary grasp of the language, history, and culture.

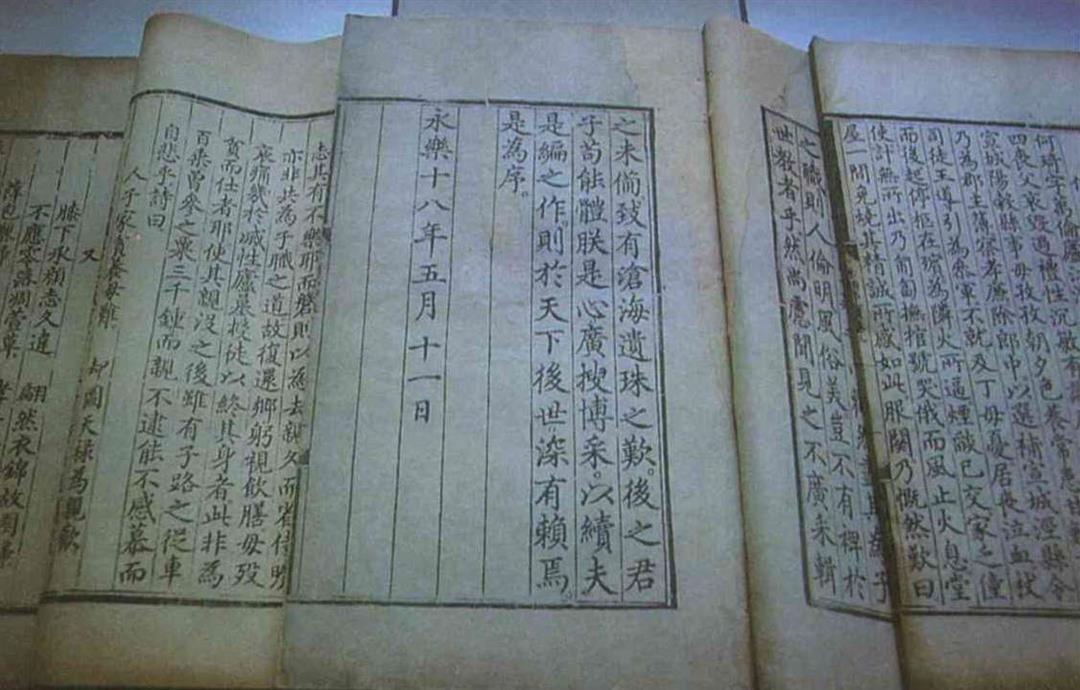

Language, of course, is the key to understanding a culture, but there are no shortcuts to learning Chinese. Who among an earlier generation of scholars did not pore away over hoary classics like the Tso chuan or the Spring and Autumn Annals?

As early as fifteen or twenty years ago teachers began using graphics, slides, and illustrations as supplementary materials to liven up the classes. But Professor Zucher also received inspiration from another source.

It came from television--not the programs but the commercials. "Commercials are often boring and ridiculous, but you have to admit that some of them manage in a few seconds to stick in your head as though you had been brainwashed," he says. "The message they transmit may not be profound, but they have a powerful effect."

Another stimulation came from short introductory films. As a consultant to the ministry of education, Professor Zucher has frequently been invited to visit large corporations, which often show a ten-minute introductory film produced by an advertising firm. "The films cost a lot to produce, but the quality is very high," he says. They are more effective in ten minutes than a one-hour lecture.

That was how he came up with the idea of using visual images to present the rich heritage of Chinese culture to students in class. It would serve to supplement and transcend the written word at the same time as it stimulated students' interest and motivation.

The concept may not have originated at Leiden's Sinology Institute, but Professor Zucher was the first to put it in practice.

The Visual Presentation of Chinese Culture project, under Professor Zucher's direction, has been going on for six years now. The production team has mobilized the resources of museums and academic institutions around the world and has already completed four six-hour presentations on "The Written Word," "China and the Outer World," "China and Europe," and "The Imperial Center" as well as a twelve-hour "Survey of Chinese History," two programs on "Buddhism in China," and features on various subtopics. A presentation on "Court Life" is in progress. "We've got 20,000 images in our resource bank," Professor Zucher points out.

Confucius' "I want no words" is the ideal aimed at in the project, Professor Zucher indicates. Expert arrangement and concentrated exposure (an average of 300 images are shown every 45 minutes, the longest for no more than 12 seconds) are designed to stimulate and impress viewers directly, unlike conventional teaching by slides, which requires lengthy explanations.

The series is currently used at the Leiden Sinology Institute, where it has been well received by students, and it has been shown at various other institutions around the world. The immediate goal is determining how the programs can best be stored and utilized. The Philips Corporation is said to have developed a new technology that can store 50,000 images on a CD-sized disk. When sinological and computer expertise are combined, we may someday be able to walk into a library, push a few buttons, and call up on a terminal all the images related to a certain subject--shoes, for instance--as they appear in Chinese materials kept in museums and libraries around the world.

That is a lovely dream. Sinology has never been a "graphic" subject in the West. The philosophes of the Enlightenment made use of a vague enthusiasm for things oriental to support their critique of contemporary society, and the imperialist powers later relied on "old China hands" to maintain a grip on their concessions and interests. It has only been during the present century that sinological institutes have finally trans-formed themselves from cradles for turning out colonial officials to true centers of academic research. But for most Westerners the Orient still remains shrouded in mystery. Arnold Toynbee may have declared long ago that the 21st century will be the Asian century, but how many humanities departments give Asia more than a passing glance in their so-called world history, literature, and philosophy courses? How many really seek to explore Western culture's other half?

"The responsibility of a sinologist, I believe, is to serve our societies as a bridge to the East," a Swedish scholar has said.

Professor Idema has written many books, but except for a few scholarly treatises in English, the rest are translations into Dutch. "The taxes paid by my fellow citizens give me a chance to study Chinese literature, so I have a duty to let them share in the enjoyment I have found in it," he explains.

Two years ago the Leiden Sinology Institute cooperated with a television station in producing a pair of programs on Chinese cooking and the Chinese language. The ratings were comparable to those for soccer matches, and a week after the show on Chinese cooking, woks were sold out in stores around the country. "We have to put on more programs and exhibitions and introduce more Chinese culture to the public," Professor Zucher says. "That is a must, and it is also a goal of the research we have worked so hard at."

In a few more years Professor Zucher will have retired from the institute he has devoted his professional life to. But before he does, his most cherished ambition is to expand and promote the Visual Presentation of Chinese Culture project. He calls it his baby, and his greatest wish is to see it grow up. His wish may not be so hard to realize. Major sinology centers in Europe and North America all plan to buy the materials, and the European Association of Chinese Studies has designated the project its number-one priority for next year. A professor of linguistics has described it as "exporting Chinese culture."

The work involved is not easy. Professor Zucher points to a pile of slides in front of him and says, "We feed them to students drop by drop."

Culture is formed drop by drop, and understanding between East and West must be built up the same way.

[Picture Caption]

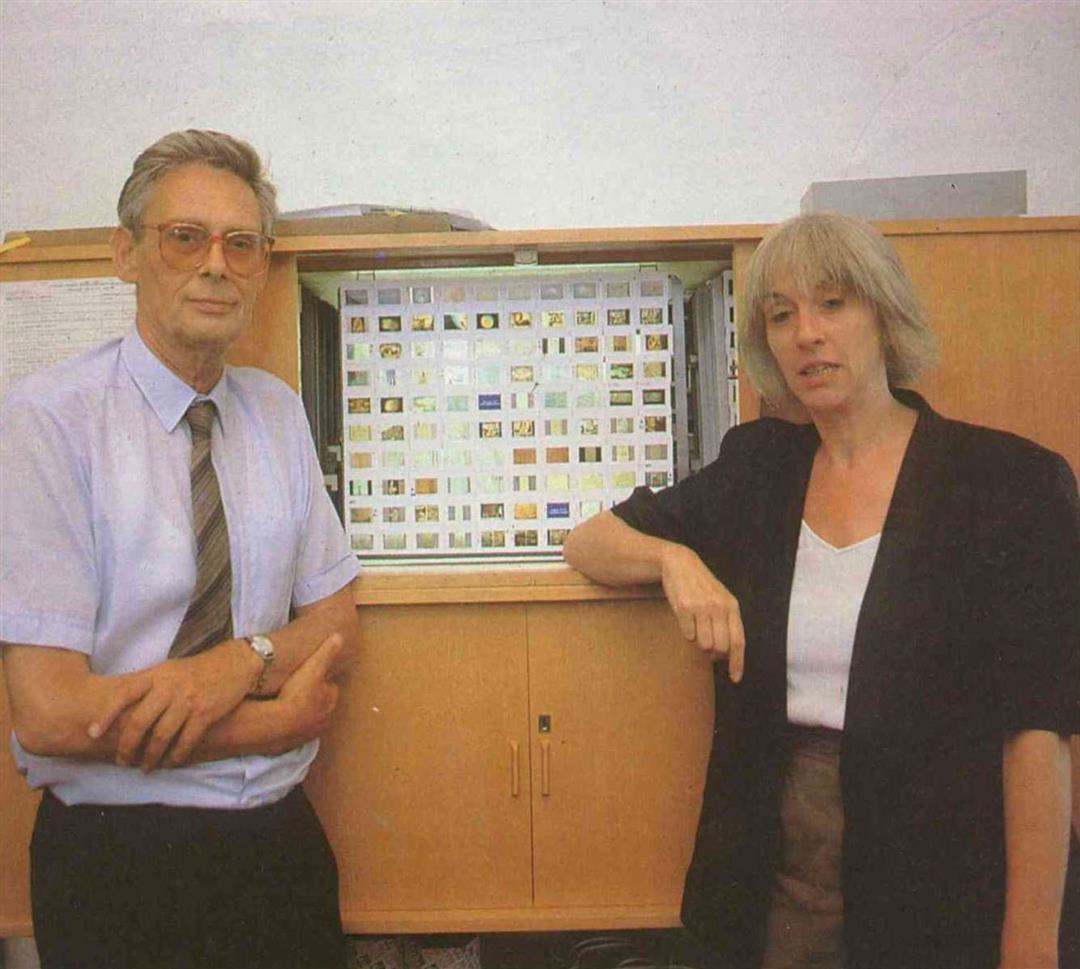

Dr. Zucher and Drs. Ellen Uitzinyter are the two main people in charge of the Visual Presentation of Chinese Culture project.

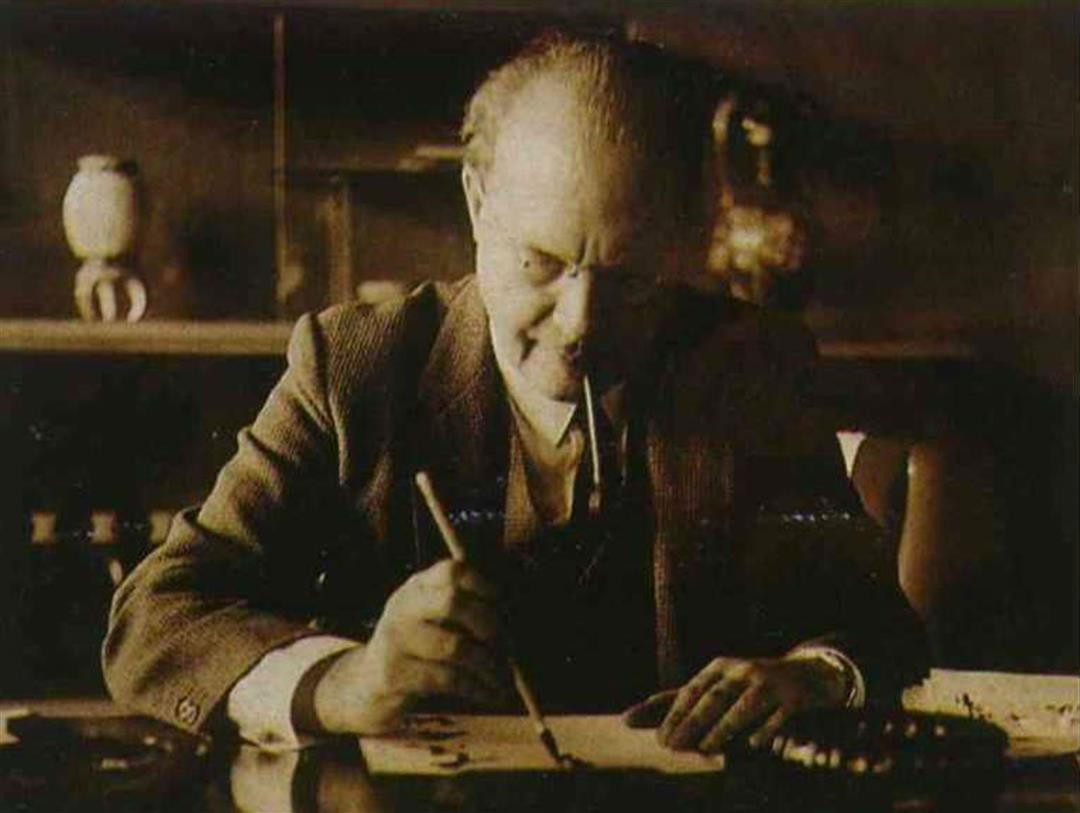

Quite a few of the older generation of sinologists were diplomats or colonial officials. The picture shows the legendary Dutch diplomat R. H. van Gulik.

The Leiden Sinology Institute has a rich collection of books. This room stores those acquired by van Gulik, an avid collector.

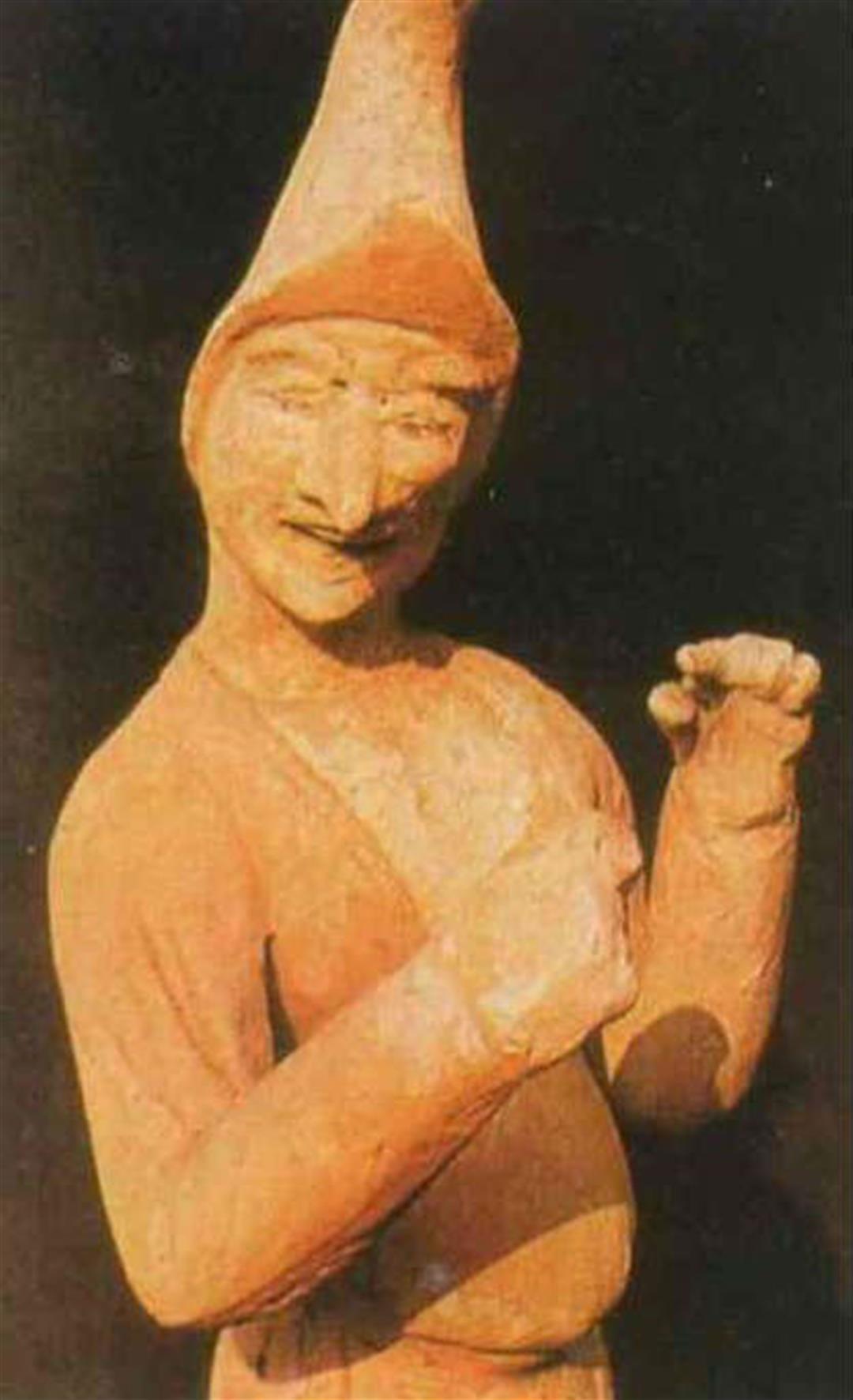

A foreigner--as seen through Chinese eyes.

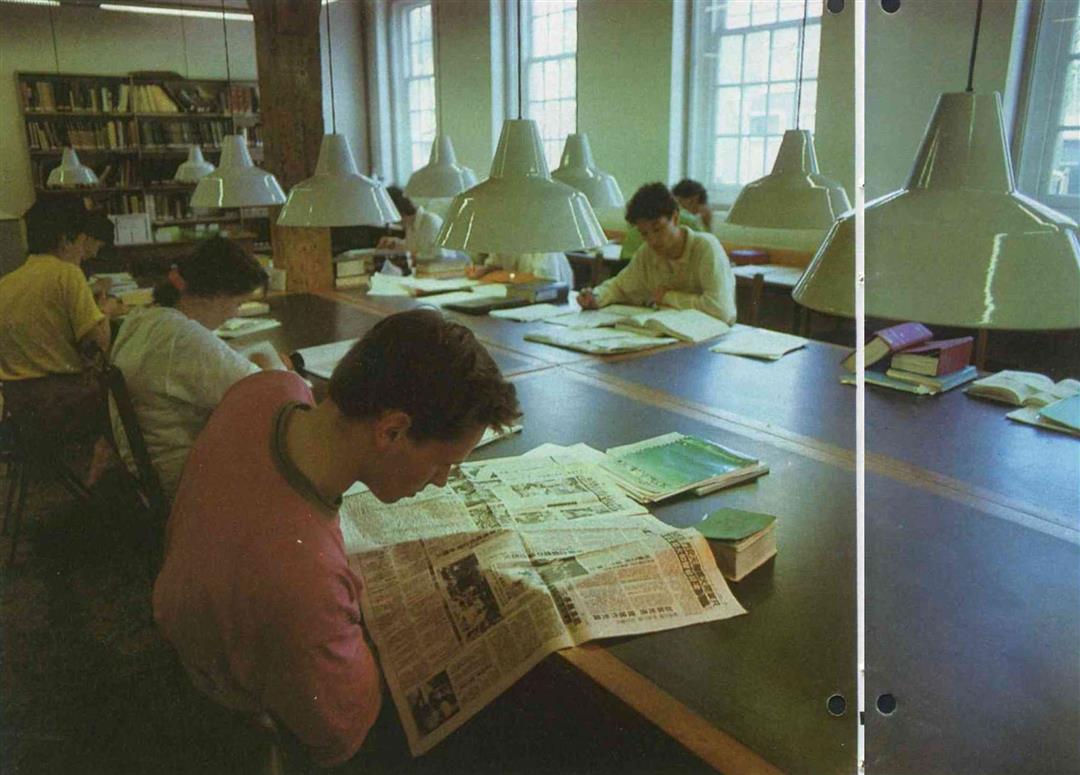

This is the library of the Sinology Institute at Leiden University. Students are reading news about the Tienanmen massacre.

A pagoda, a palanquin, and a five-pointed beard are frequent elements in paintings of China by Westerners.

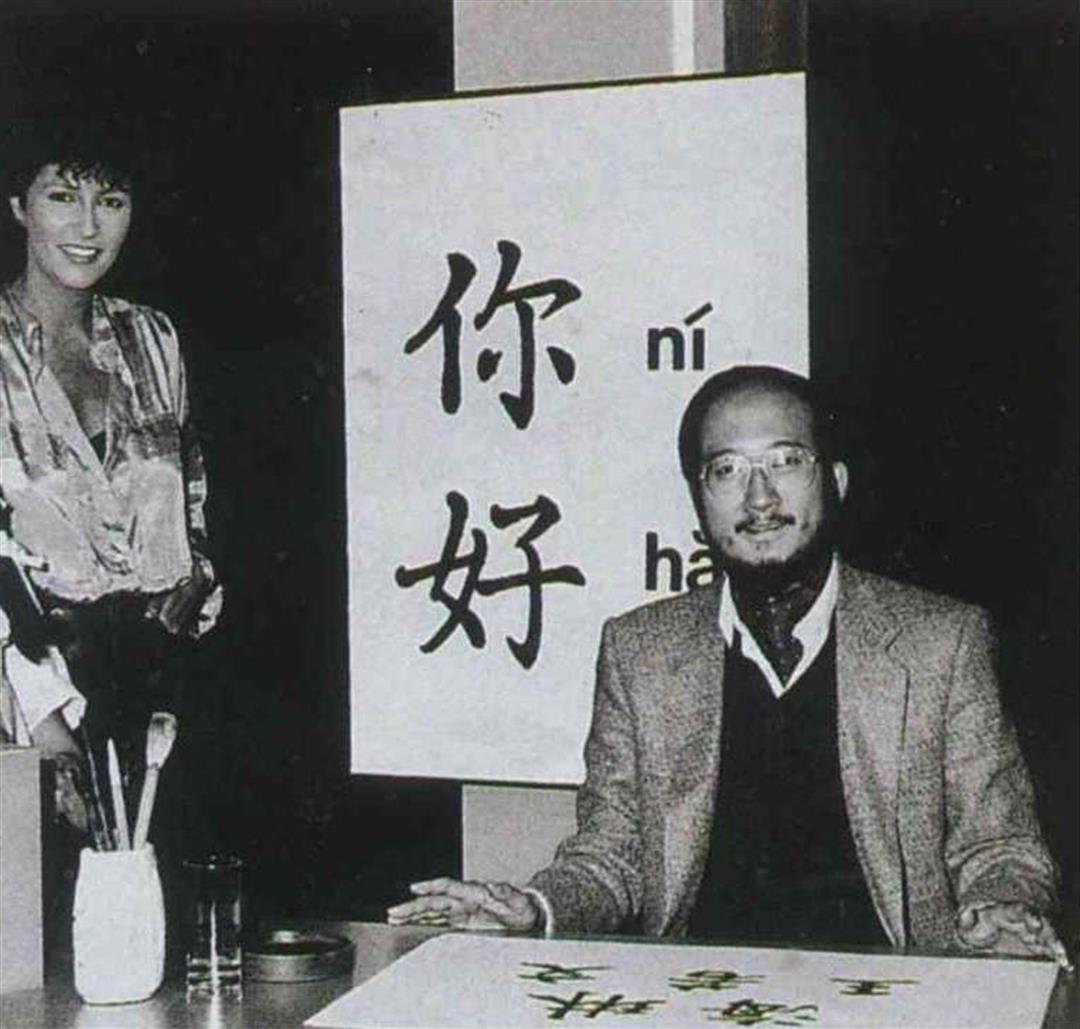

The Sinology Institute cooperated with a TV station in the Netherlands in producing a program on the Chinese language that proved quite popular.

How many interesting things can you find in this Oriental market?

Dr. Zucher and Drs. Ellen Uitzinyter are the two main people in charge of the Visual Presentation of Chinese Culture project.

Quite a few of the older generation of sinologists were diplomats or colonial officials. The picture shows the legendary Dutch diplomat R. H. van Gulik.

The Leiden Sinology Institute has a rich collection of books. This room stores those acquired by van Gulik, an avid collector.

A foreigner--as seen through Chinese eyes.

This is the library of the Sinology Institute at Leiden University. Students are reading news about the Tienanmen massacre.

A pagoda, a palanquin, and a five-pointed beard are frequent elements in paintings of China by Westerners.

The Sinology Institute cooperated with a TV station in the Netherlands in producing a program on the Chinese language that proved quite popular.

How many interesting things can you find in this Oriental market?