A busy intersection. Before us is a young man clad in an open denim jacket, canvas bag on his back, camera in one hand, zoom lens in the other. His face is rectangular, carries glasses, and is marked by a deep brow, as if he were squinting into the sun.

This was originally a picture--now it is a self-portrait of Han Hsiang-ning. The portrait is a composite of fine points of paint, like particles floating in the air. The process of transition from photo to painting is like this: first the photo is projected onto the canvas with a lamp. Then the outline of the image is sketched onto the canvas. Then, a cut paper pattern of the image is made. The artist then takes acrylic spray paint, and, covering up all but the target area on the canvas with the cut paper, sprays on the color desired for the remaining, uncovered area, from a distance of one or two feet. This process is repeated one or two hundred times to get a finished picture. The time can take anywhere from two weeks to three months.

The use of photos for subjects led some to put Han in the photo-realist school. The use of points of paint to compose an image led others to call him a "neoimpressionist." For Han, "Regardless of what category one belongs to, the important thing is creativity and whether or not one has a unique personal style."

Hung in his Soho home alongside his self-portrait are scenes of buildings, the streets of New York, crowds, and scenes from his birthplace--Chungking. And in the paintings are written the story of Han's twenty years in Soho.

Han's warehouse/studio, long and narrow like Hsia Yang's, is nevertheless completely different. The latter's was busy and cluttered. Han's can be divided into three parts: near the window is a stereo, with tall narrow speakers and a vacuum tube amplifier; in the middle is a wooden bench fit for two--located perfectly for listening to the music; finally, near the wall is a long table. There are soft lights set on the floor playing on the paintings. And that is all.

The room is filled with the sound of classical music, but the resident's casual clothes and round glasses are completely modern. It is hard to tell that he is nearly fifty, and part of the older "May Group" generation.

The May Group was comprised of a group of very young artists, all steeped in modern literature and classical music. They often got together to discuss the deeper meanings behind the relationship between modern and traditional. At that time Han's works were largely abstract, with inspiration coming nonetheless from Shang dynasty brass or fragments of ancient oracle bones.

In 1967 Han struck out alone for New York. He arrived just in time to catch the Beatles frenzy. "Their music was really alive, and moved me. In comparison, Beethoven seemed passe." It's only in the last year or two that Han has turned back to classical music.

From Beethoven to the Beatles, Taipei to Soho, and abstracts to photo-realism --enormous changes, yet quite natural for Han, who has had little trouble adapting.

"In the 1960's Hsi Teh-chin introduced Pop art to Taipei. I really felt sympathetic vibrations, and tried paintings with rollers. Many of my friends did not approve, and said that this was purely American entertainment; but I believed that it was part of modern culture, and really alive. I liked it."

"In those days," he says, "many of my friends went to Paris, but I heard that New York was cheaper to support oneself, and I thought I could throw myself in for a while."

In his first year in the Big Apple, he worked at an advertising agency while hitting the galleries and museums in his spare time. He saw what was on the cutting edge of art, and came to feel that his own was inadequately modern, inadequately developed. He saw that the work of the artists was intimately connected to their life in New York. It was a natural step, then, for him to turn to subjects near at hand, and then to photo-realism.

He explains, "In terms of tools, I like to continually experiment. I felt that the minimalist art then rising in New York was excellent, and I started to use a paint gun instead of a brush, and acrylic paints for light points of color."

The first things to make the canvas were the symbols of industrial civilization: huge bridges, skyscrapers, factories, and Soho's aged structures. He took his camera on safari on the streets of New York. For every one or two hundred photos, he would choose one or two compositions to turn into paintings.

In 1971, Han had a showing in the O.K. Harris Works of Art, famous for promoting photo-realism. In 1976 he won an award as one of the one hundred most distinguished foreign-born artists in the U.S. on the occasion of the bicentennial, and his work was collected by Washington's Hirsch-horn Museum.

Though the high tide of photo-realism is now past, Han continues to work in this style. In his view, no matter what the "ism," each style of painting will have its heyday; but each movement can only have significance as one stage or step. But, unlike clothes, art endures. "Although impressionism is past, no one would say that a Renoir has no value, or is no good."

So perhaps photo-realism isn't the trend of the eighties. Han says that the only big difference is that there are fewer large-scale shows or group shows. He emphasizes, "I haven't gotten into any new movement because there is no need. I still have a lot of things I haven't finished yet."

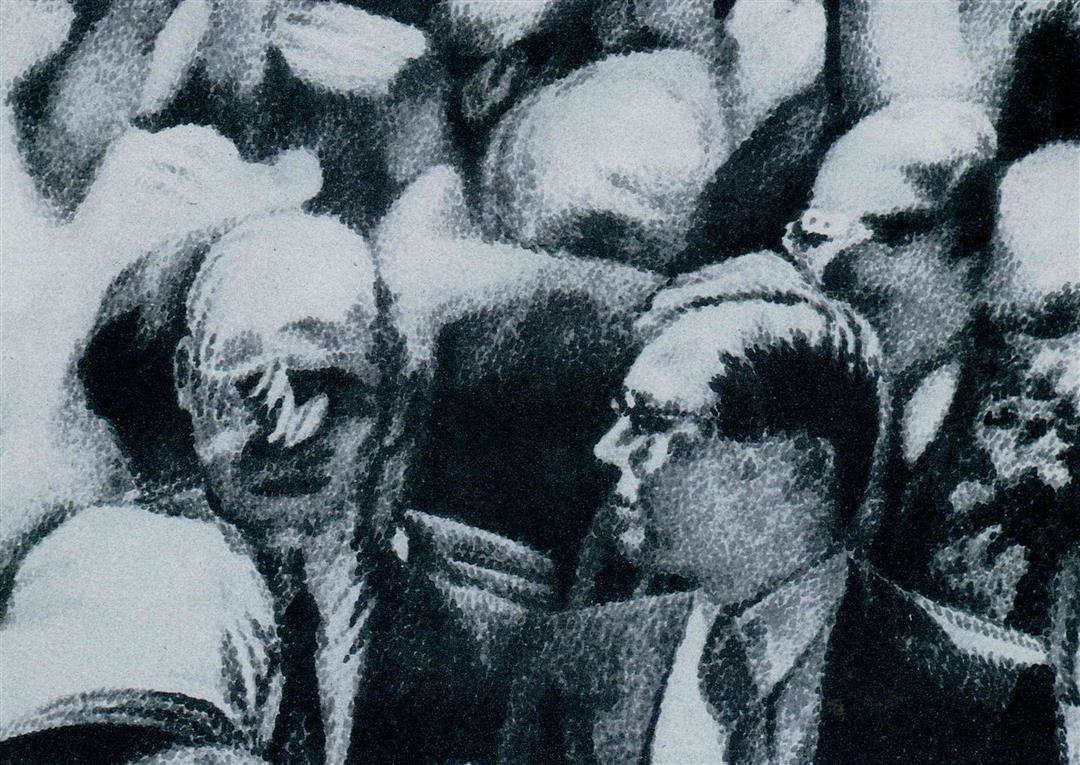

For the last ten years, although the style has not changed, the subject matter has. Since 1977 Han has focused primarily on people as subjects. He likes to take his pictures with zoom lenses from atop tall buildings.

Some art students have asked Han whether or not relying on photos is limiting. Han simply responds, "Van Gogh loved to use orange color; was he limited by his colors?" Han explains further that in the nineteenth century Pissarro also liked the birds'-eye-view perspective. But he was limited to the use of the naked eye. We have one hundred years, so "why can't twentieth century artists use the tools produced by modern civilization?"

"From ancient times to now, artists have been selecting their own tools. Primitive man could carve an animal on a rock because he finally understood how to use tools. Later someone invented the brush, and everyone used the brush. Today the choice of tools is much larger, simply because we are not willing to be limited by our tools."

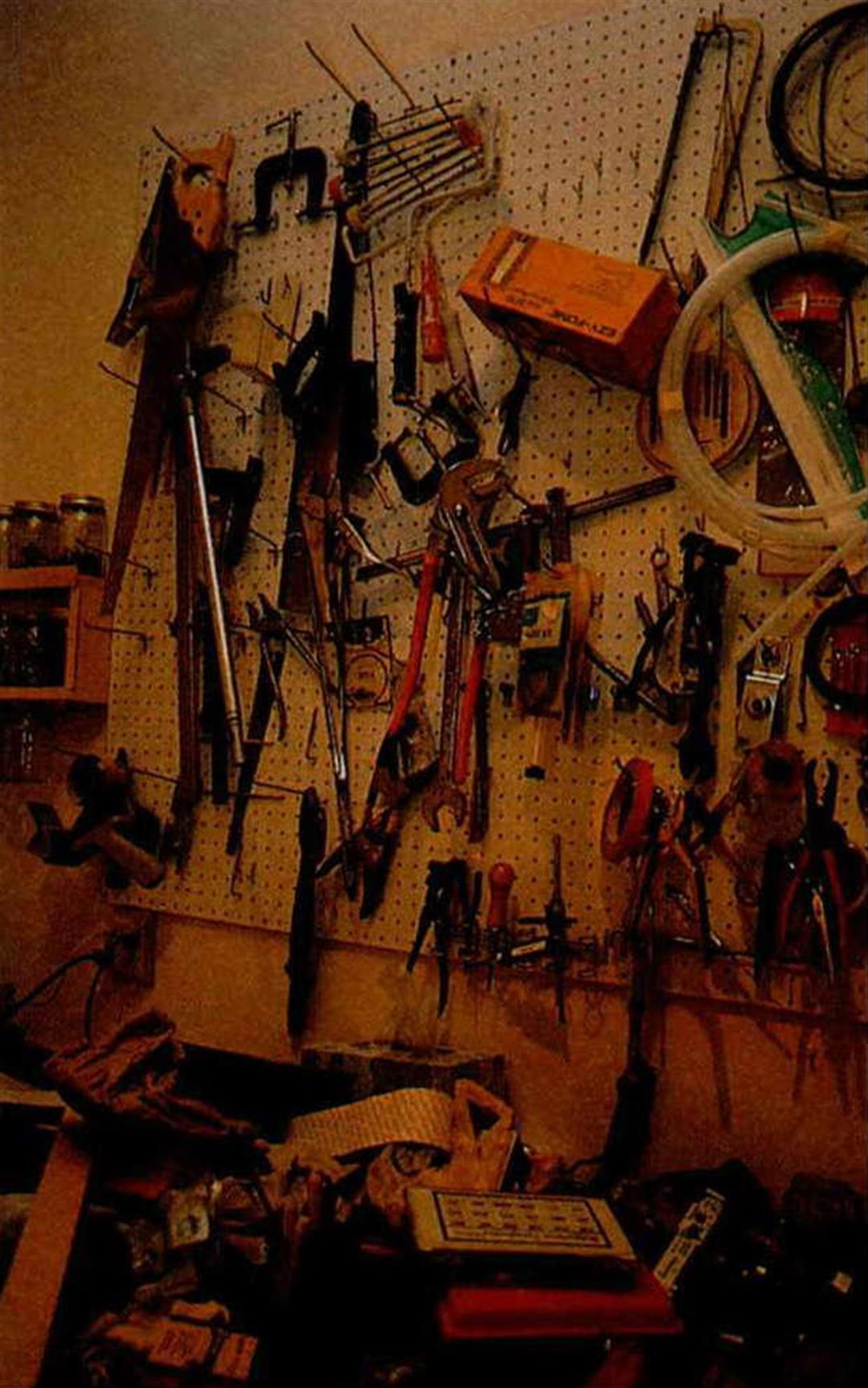

Han's Soho studio floor is covered with cut paper from his spray paintings, and the walls are loaded down with tools. But in his new studio in the countryside, there are no spray guns and no collection of colors. There he relies on a brush to do black-and-white paintings which carry a flavor resembling the special Chinese technique of representing irregular surfaces. "Some people have that these have absorbed the influence of expressionism."

The black-and-white paintings are nonetheless still of industrial civilization: crowds of people with hurrying steps and perplexed faces. . . . After living in New York himself for twenty years, what has been the impact on Han Hsiang-ning?

"New York life is certainly intense," he says, sitting contentedly on the floor in front of the table, gesticulating with his hands for emphasis. "Some people can't stand it and find it difficult. But I think that you only have to grasp the rhythm, and then it can be an exciting style of life."

[Picture Caption]

Curly hair, sparse mustache, and round glasses--does he look like someone pushing fifty?

Street Crowd, one of Han's recent works, 26"×40".

This is the workroom in all its splendor.

Will their owner be "limited" by this wallful of tools?

Street Crowd, one of Han's recent works, 26"×40".

This is the workroom in all its splendor.

Will their owner be "limited" by this wallful of tools?