In recent times, demands that gender roles be redefined have led to very fast changes in Taiwan's society. Traditional family relationships have encountered the difficult problem of adaptation. In debate everywhere, men are the target of attacks. But, in fact, more and more fathers had already been getting involved in the education of their children, and sharing their experiences with their families and their innermost feelings with others. Among these fathers, those attracting the most attention are those who are writers. They have taken their delicate writers' sensibilities, and applied them to their own experiences of fatherhood to write books. The level of popularity of these books reveals something about people's innermost yearning. . . .

A cold wind blows and the rain patters down. In the chill, dark damp of the long corridor outside the National Taiwan University (NTU) Hospital's birthing room, Lin Liang sits alone, listening so intently that he can hear his own heart beating. Each cry of pain from a mother giving birth, every tearful wail from a newborn baby coming to him from inside, makes his heart skip a beat.

While fear and expectation battle inside him, a little girl is finally born.

This was just after Taiwan's retrocession, when the ROC government had not long moved to the island. People were uncertain and fearful. Life's necessities were in short supply. The arrival of an infant meant all kinds of real, practical problems for its parents. Especially in the endless rain, in that era of no washing machines and no dryers, diapers created an indoor disaster.

"It seemed that wrapped up inside her blanket was a little printing press, printing sheet after sheet of warm, damp, pale yellow diapers. . . One began to hear the sound of hammers from our bedroom. We put up steel wires, one, two, three, four, five, six. Her diapers looked like military banners flying in the rain, filling the room with an impressive display of might. We walked stooped over under the diapers. . . . The free space on the desk was also taken over. Near-sighted writer that I am, I often punctuated drops of water that had dripped down from the diapers above."

But all of these various annoyances were viewed by the girl's parents as "the happiest anguish," and "the sweetest suffering." They felt that this little baby girl was a little sun that made them forget the cold, wet world outside.

A little sun forever

Lin Liang, who writes under the name of Tzi Ming, wrote of the birth of his eldest daughter in his essay "Little Sun" from his most popular collection of essays, Little Sun.

The collection gathers together his works from the period 1956-1970, all of which focus on his family life. Over fifteen years, from his description of the period just after his marriage when he and his wife could just afford a chilly one-room apartment in "One-room Home," to the last essay, "Little Grasshopper," his family grew to six members: he, his wife, three daughters and a white fox terrier.

With the publication of the collection, this family became the "little sun" of many Taiwanese families. In the 25 years since Little Sun was published in 1972, it has gone through 100 printings and sold 300,000 volumes. Its slow and steady sales have made it a rarity among domestic books.

Little Sun's success derives from its clear and delicate writing, its vivid and humorous descriptions of warm family scenes, and that lovable father. He is warm, funny, easy to talk to, loves his family, enjoys spending time with his kids, and is not even a little bit high-handed.

He was a father who could do everything. He spent his days as a newspaper editor. Late at night, he buried himself in his writing. In addition, he took care of his kids, dealing with their illnesses, their sadnesses, and their problems at school by himself. In spite of a limited budget, he even often managed to take his children travelling. And what was really exceptional was that when the children began to grow up, this hard-working, caring father knew how much room to give them to let them learn to be independent.

Sentimental huband

Lin Liang was a member of the first generation to establish families after the war. But compared to most of the men of his generation, his character is rather unique.

The 46-year-old Hsiao Yeh, an author, says he read Lin Liang's works as a youth and found it hard to believe that there was such a good father anywhere in the world. "Most fathers at that time maintained a severe and dignified demeanor. They found it difficult to communicate and to express their feelings. They didn't even allow their families to speak at meals." He says, "But Lin Liang always seemed to be smiling, to be warmer than a mother. He wasn't demanding with his children, never giving them any pressure. And he was very reasonable in teaching them and communicating with them." The book created a longing within Hsiao Yeh, whose relations with his father were tense. It was also a source of comfort.

The 70-plus-year-old Lin Liang, who currently serves as the chairman of the board of the Mandarin Daily News, says that over the years, many young readers have written to him after reading Little Sun, asking him to be their father. He himself feels that what is special about his work is that these essays are an on-the-spot account of his family life at that time. They are like photographs. Some emotion was felt and immediately captured, so many details and conversations were preserved. "When I reread them, they still have a lot of flavor," he says.

Author Chiu Hsiu-chi opines that few works by writers of that era were as sentimental as those of Lin Liang. "In general, traditional thinking was still prevalent at that time. [Writers] thought that writing in such a way would mean losing their male dignity. So, even if they felt great love for their family and their children, their works rarely involved themselves with the little details of family life," she says.

"I, too, have my pride," admits Lin Liang. He, too, cannot completely cast aside traditional thinking. For example, although not unwilling to do household chores, if a friend comes to visit, he will immediately stop, destroy all evidence that he was doing housework, and assume the air of the manly and dignified master of the house to welcome his guest.

"When I write, I always set out with the belief that every family has its lovable points. I hope and do my best to reveal the interesting portions of everyday family life. I'm not trying to make a model family," he explains.

A child's heart

On the other hand, writer Liao Yu-hui thinks that traces of Lin Liang's style can be found in traditional literature. Liao, an assistant professor of literary history at National Chung Cheng University, thinks that some of the Chinese literati were softer, warmer, and more sensitive. These writers admired the naturalness and purity of children, and so often used children to give allegorical expression to these feelings, contrasting these traits with the ambiguous nature of human affairs. They allowed themselves to take comfort in the naivet* and guilelessness of children.

In more modern times, the early Republican writer Feng Zikai was certainly one who greatly enjoyed describing children. In one work, entitled "For My Children," he wrote:

"In this world, I have never encountered anyone so willing to expose their inner being as you. Among all the people of the world, there have never been any so honest and so pure. When I return from a trip to Shanghai to take care of some boring but allegedly 'important affair,' or from that vaudeville for people with whom I have nothing in common called 'teaching class,' I see you standing in the doorway or at the station waiting for me and my heart is filled with shame and joy. Ashamed at why I went to these kinds of boring things. And joyful because I can once again put aside everything for a short time and reenter the real life that is yours."

Nevertheless, Feng recognized that the real world is heartless and that children grow up. These kinds of sorrows caused him to put his all into creating writings and paintings with children as the subject. "My children! I who so yearn for your life have a silly wish to preserve this golden age for you forever in these books. But, like 'catching fallen flowers in a spider's web,' it will only retain a few traces of the spring."

Western styles have gradually blown east and modern literati have quite happily absorbed their time's more liberal Western educational methods. In "Being a Father," Feng examines the contradictions in his own approach to education. The essay describes a vendor selling chicks in front of their gate early one spring afternoon. The children, who loved small animals, were so taken with the chicks that they wouldn't put them down. One after another, they asked their father to buy a chick. But the vendor's price was too high; he had obviously decided to take advantage of the situation. In the end, they could not reach an agreement on the price and the vendor left in a huff.

Facing his tearful children, Feng wants to tell them that the next time they see something they like, it would be best not to reveal their feelings to avoid people recognizing those feelings and using them to get the upper hand in negotiations. But, halfway through his speech, he realized he was teaching the children to be sly, to say things other than what they felt, and couldn't go on. "'When you see something good, you can't say it is good. When you want something, you can't say that you want it.' If you take this a step further, it becomes, 'If you see something good, you ought to say it is bad. And if you want something, you ought to say you do not.' In the midst of this brilliant, pure, upright and honest spring scene, where was a father who teaches his children this kind of thing to hide?"

Liu Yung's trick: IQ plus EQ

Recently, even best-selling writer Liu Yung has directly brought up practical principles for the living of a life in his I Won't Teach You Cunning. Liu may be considered one of modern society's outstanding fathers. So, how did he deal with his half-grown son, a son who had grown up in the interstices between East and West?

At a New York subway station exit, everyone is caught up in the rat race. Only Liu has his feet planted, waiting. He stares anxiously at the faces of those emerging from the station, a recent news story on his mind: A pregnant Chinese woman was pushed onto the subway tracks by a mental patient and crushed to death by a train. Another woman lost her footing. . . . Liu knows that this is the most unsafe and chaotic place in the world.

But from today, his 16-year-old son will be traveling through this urban jungle, with its poisonous snakes and its wild beasts, every day to get to class at Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan. Even though he took his son on a thorough trial run of the route two days ago, he is still worried. He estimated his son's return time and has come to the subway exit to wait for him.

At last, the boy appears. The excited father meets his son again as if they have been separated for many years, a hundred feelings stirring in his heart. He also sees that in his son's surprised and pleased expression, there is a gleam of tears. In that instant, he suddenly realizes that from this moment forward, his son will begin to make his own path through life.

"This son who used to obey my every whim had suddenly grown up. His voice became rough almost overnight. In a flash, he became half a fist taller than me. I used to bow my head to tell him what was what, but now, like it or no, I must look up to admonish him. . . . My reign as the only authority in the house has passed. . . . My boy has begun to have his own values, his own view of life. He no longer belongs to his parents, but to society. He no longer is his parents' shadow, but is himself."

Liu Yung, born in 1949, is twenty-some years younger than Lin Liang. He graduated from the art department of National Taiwan Normal University (NTNU) and worked for a time as a news reporter for the China Television Company. In 1978, with recommendations from the Government Information Office (GIO) and the National Museum of History, he went to the United States to teach. The next year, he began to teach at New York's St. John's University. Liu can be considered to be a member of the second generation of fathers to establish families after the war and his family, a typical example of an immigrant family.

In addition to his news, art, and teaching work, Liu writes books. In the past, his books, full of determination to achieve one's goals and a pro-active view on life, achieved broad popularity among Taiwanese, and were especially loved by students. In 1988, his own son entered high school and he realized that the boy had entered his pivotal teen years. The father-son relationship had to undergo some adjustments. He began to write a book in the form of letters to his son.

At the end of 1988, he gathered these letters together and published them as Overcoming Yourself. It was followed by Creating Yourself and Affirming Yourself. In the years following, as his son grew older, Liu focused on his son's different needs as he passed through university and graduate school, publishing many books of his discussions with his son about life's meaning and values. However, it is the three books above that have seen the most consistent sales over the years. The teen years are everyone's biggest headache and these three books provide both parents and students with something to consult during these difficult times.

Why Chinese students excel

"When children are growing up, traditionally, the typical model that parents apply in teaching their children is to focus continuously on their needs, providing guidance and reminders," says Liao Yu-hui. According to Liao, what is rather unusual about Liu is that you can see in his works that he was making a sincere effort to learn and mature with his son.

"Although modern parents admire liberal education, they must still provide constant guidance to their children, especially in the teen years. Teenagers do not yet have a firm grasp on life's principles and parents must help them build an appropriate value system," she says. But she goes on to say that most parents, especially fathers who are teaching their children a lesson, are often too severe. They tend to express themselves through nit-picking and scolding to conceal their worries and their care. In this respect, she continues, Liu's works have achieved a more balanced approach.

Liu also emphasizes that he is continuously adapting his educational methodology. Because his own father died when he was nine years old, Liu was raised by his widowed mother. While still a child, a fire completely destroyed the family's property. They lived in poverty and Liu relied entirely upon his own force of will, studying with great diligence, striving to get ahead. Given his own background, when Liu began the education of his son, he expected a great deal from the boy and gave him a lot of pressure. "When my son was born, I was only 23 and had just begun my working career. I was fighting to move up, and, in a similar manner, was very demanding with my son."

"I remember I went to Europe one year. When I came back, my boy came over to give me a hug, never thinking that the first sentence out of my mouth would be, 'Have you memorized the National Phonetic Symbols?'" (The National Phonetic symbols are a sort of "alphabet" for Chinese.) Just after immigrating to the United States, a stubborn determination that his child would learn about Chinese culture led him to rule that the boy, who was in second grade at the time, would memorize "A Record of the Yue-yang Pavilion" and "A Record of the Peach-blossom Fount," two difficult works of classical Chinese literature.

Later, Liu gradually accepted and learned the American educational method. He began to adjust his own over-bearing style and spent more time with his boy. He also began to try to express his feelings, making a habit of going jogging with his son, and working at communicating with him while doing so.

In spite of the popularity of his books, which are taken as educational "reference books" by many Taiwanese, he says, "Every family has a different set of values, a different background, and a different structure. Therefore, the shape of the parent-child relationship that develops is different. Everyone can't use the same way." He goes on to say that you must continue to grow. And you must adjust your approach based on your life experience and what you wish to give back to your family. To him, this is a more liberal method of education.

Mad Old Dear and EQ?

It was raining on Lunar New Year's Eve. Famous author Hsiao Yeh and his wife were cooking dinner and setting the table with their son and daughter. While they arranged things, they thought up names for the dishes: "Castrated Chicken Dismembered by Dong Fang Bu Bai"; "Guanyin's Willow-waisted Flowers"; "Japan's First Exploding Bullets." Their purpose was to entertain Hsiao Yeh's aging parents.

Near the end of the family dinner, Hsiao Yeh's father suddenly and unexpectedly called Hsiao Yeh and his sisters to his side. He began to tell them of the efforts he had made and the youth he'd spent on their behalf. He talked until his grief overcame him and he began to cry. It never occurred to him that the son and daughters before him might also have a belly-full of grievances. His talk had pricked their memories and they began to return their father's attack. In the end, the old man's authority lay on the floor, having been trampled by his grown children. Unable to speak, he slunk out of the room.

The next day, Hsiao Yeh took his wife and children back to his parents house to offer New Year's wishes. His son played up to his grandfather, taking Hsiao Yeh's place in smoothing over the previous night's social disaster. Hsiao Yeh himself went off silently to clean the bathroom for his father. "I put my back into scrubbing away the faint smell of urine in the toilet, just as if I were scrubbing away the insults I had received growing up. I hoped to make a brand-new soul to accompany my body into old age, a soul without complaint or regret."

This is one scene from Hsiao Yeh's Mad Old Dear, his book describing his relationship with his father. In this scene, he presents the relationship between the three generations of men in his family.

In 1990, Hsiao Yeh, whose real name is Li Yuan, began to publish works on family and on fathers and sons. The first of these to be published, To My Son Who Wants to Roam, immediately became a best-seller. For Hsiao Yeh, who developed the habit of keeping a diary as a child, the book is a 10-year record of his family life, beginning with the birth of his son. His son, daughter, wife, father and mother all appear as characters in the book.

"He deals with his children as if they are 'pals,' and is brave enough to reflect on his mistakes and give expression to his softer side," says fellow writer Liao Yu-hui, who is almost the same age. She feels that people of their generation are caught between two eras, and face the conflict of tradition versus modernity, closure versus openness. She feels that this is the most difficult dilemma the members of their generation face as fathers and mothers in this life.

A vessel for their hopes?

"My father wasn't as perfect as Lin Liang, but he put his heart into running the family. He took us to the botanical gardens to paint and to museums to see exhibitions. At home, he organized activities, like cai deng mi, a traditional game of riddles, during the Lantern Festival. He also worked hard at giving us guidance. From the time we were small, there was a rule that we had to keep diaries which we had to give him to critique. He also bought many non-textbooks for us from the used-book store. He had us read through them one level at a time and write reports on them," says Hsiao Yeh. These activities developed his strong creativity and his sympathetic heart. Comparing himself to friends, he feels fortunate.

However, the process of growing up also made him feel frustrated, and often unhappy. "My son reminded me of this when he asked me, 'Dad, why do you have this expression on your face like it's the end of the world?'" The question startled him into thinking he had inherited his father's expression. His father's unhappiness came from the struggling with poverty and having too high hopes for his children.

"He was very diligent about managing our childhoods, but his hopes for us were an extension of his own ambitions. He was an orphan with no father to spend time with and emulate. His children became like fields which he sowed with great effort, awaiting the future harvest of his hopes. When we didn't achieve those, his expression became hopeless and desolate," says Hsiao Yeh.

Once, when as a middle school student HsiaoYeh did badly on a test, his father knelt down before him. Now, even though the children have grown up, he maintains his powerful position. Of the five children in the family, all but Hsiao Yeh's younger brother, who lives in the United States, still live near their father's home. And these four middle-aged children still often cluster about him on walks in the mountains.

Expelling grievances with good fortune

Hsiao Yeh's wife and children have redeemed his grievances. He explains that when he was younger, he carried on his father's educational method, using it with is own children. However, the negative response of his children pushed him to continuously make adjustments and learn. After his relationship to his children improved, they developed feelings and understanding for one another like that of friends. Through this process, he has recovered his energy and his childlike simplicity.

"Adults suffer from life in the real world; it frustrates and fatigues them. In this situation, children's creativity, curiosity, and open-mindedness can be a source of stimulation," says Hsiao Yeh. Admitting that he himself is getting more playful and childlike, he uses "second childhood" to describe the feeling. This process and his writing have had a healing effect, helping to drive out the shadow of his father's authority and his childhood unhappiness.

"If men let themselves be bound by the limitations of the stereotypical male role and don't change with the times, their lack of adaptation will, in the end, leave them lost and isolated. They will be the group that suffers the most," he says.

In Lin Liang's day, men had to conceal whatever housework they might be doing, but Hsiao Yeh doesn't care in the least about how other people may see it. Three years ago, when Hsiao Yeh began to attend the Parents' Association meetings at his children's school, he noticed that he was the only father in attendance. From that time forward, he volunteered to attend every meeting. He doesn't worry that his attendance will make others think that he is a man who has nothing to do with his time. He doesn't find it demeaning or feel ashamed about attending. Instead, he feels sorry for men who don't know what sweet good fortune it is to have this kind of relationship with your children.

"The shock of equal rights for men and women, the division of roles in double-income families, men's awakening, all of these have made it impossible for modern men not share in the housework and participate in their children's education," opines Chang Pen-sheng, an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology at Soochow University. He goes on to say that modern psychological research shows again and again that the possible effects of having an "absent father" include identity problems and the lack interactive learning, causing the children's personalities to tend towards extremes.

Don't overdo it

The expression of love is learned and though perhaps familial love is everlasting, there is nothing in parent-child relationships, either on their surface or beneath it, that is absolute. As Taiwan's society undergoes all sorts of changes, these books on parent-child relationships not only describe a love that is immutable, but also show these very social metamorphoses.

Asking fathers to spend a little more time and effort on their families does not imply they should take on a mother's role, or become the kind of model father who gives up his job, and finds joy in changing diapers and holding baby bottles. "In fact, for the normal, healthy development of a child, what is most necessary is that the parents get along well, that they communicate about how to raise their children. It is not necessary that parental roles be rigidly defined, or that there be an overly devoted super father or mother," thinks Chang.

In fact, an appropriately enterprising and achievement-oriented father, when planning his career, need only be willing to consider his wife and children's wishes, be considerate of his wife, be willing to take responsibility for some of the housework, be patient with the children and be willing to let them be close to be considered a high-EQ, genius of a dad.

p.37

Modern men are more and more able to open themselves up and reveal their emotions, making parent-child relationships more pluralistic and more balanced (facing page). But years ago fathers as warm and considerate as Lin Liang, author of Little Sun, were rarely seen and many children wanted to become his child. The picture shows Lin Liang with his family.

(courtesy of Lin Liang)

p.38

Every child is a unique individual with their own path in life to follow. Respecting their independence and enjoying their world is one of the essential elements of a parent's EQ.

p.39

Children acquire their values and way of life, things which may influence their entire life, from their parents. Adapting and choosing what to teach is one of the great difficulties of modern parenting.

p.40

The illustration shows a cartoon by Feng Zikai. Children's simplicity and naturalness are the source of his creative material and his inspiration.

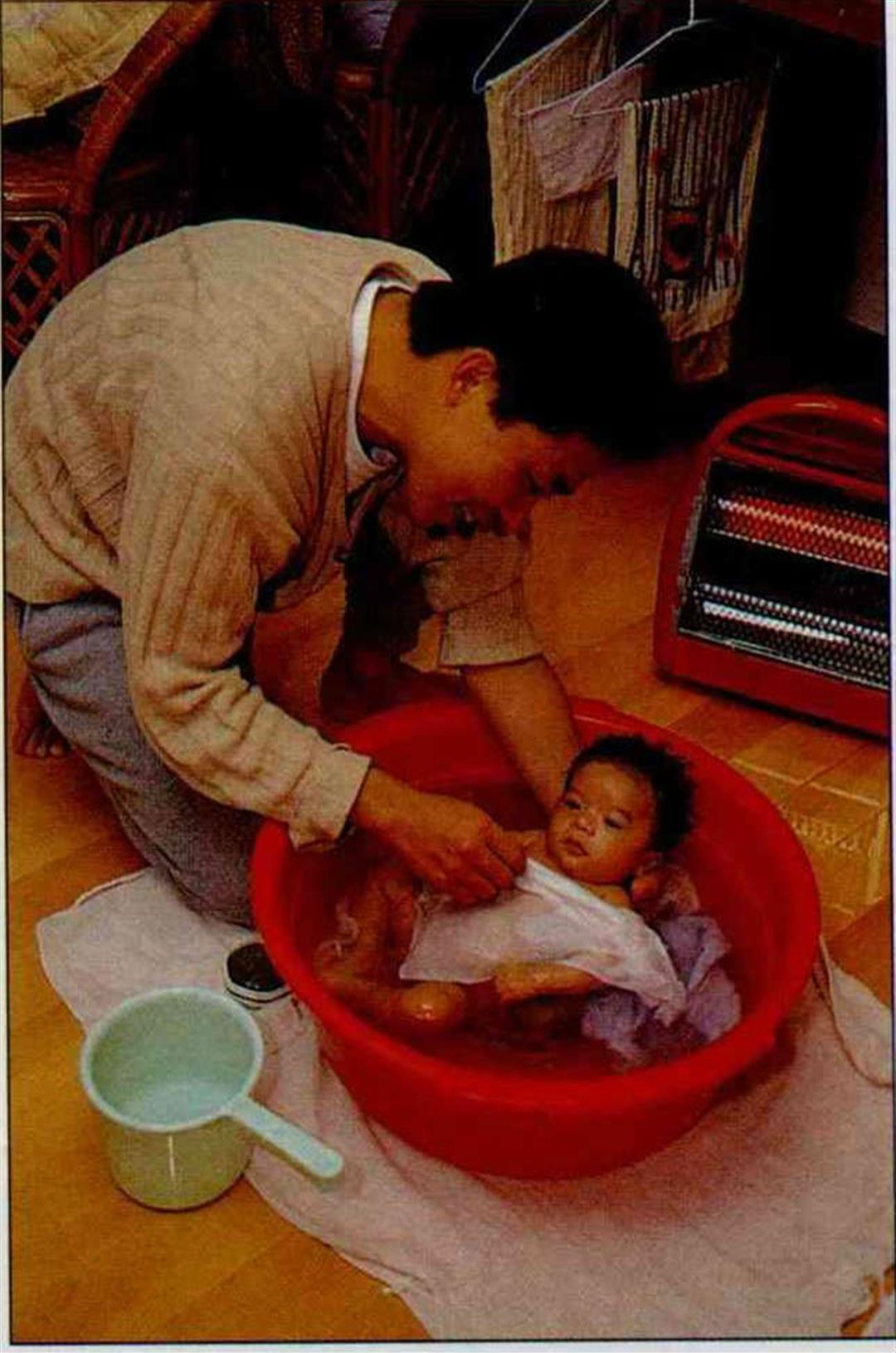

The modern division of parental roles tends toward having each parent do those things for which he or she has aptitude. There are many men who do housework with more delicacy than women. (photo by Huang Li-feng)

p.41

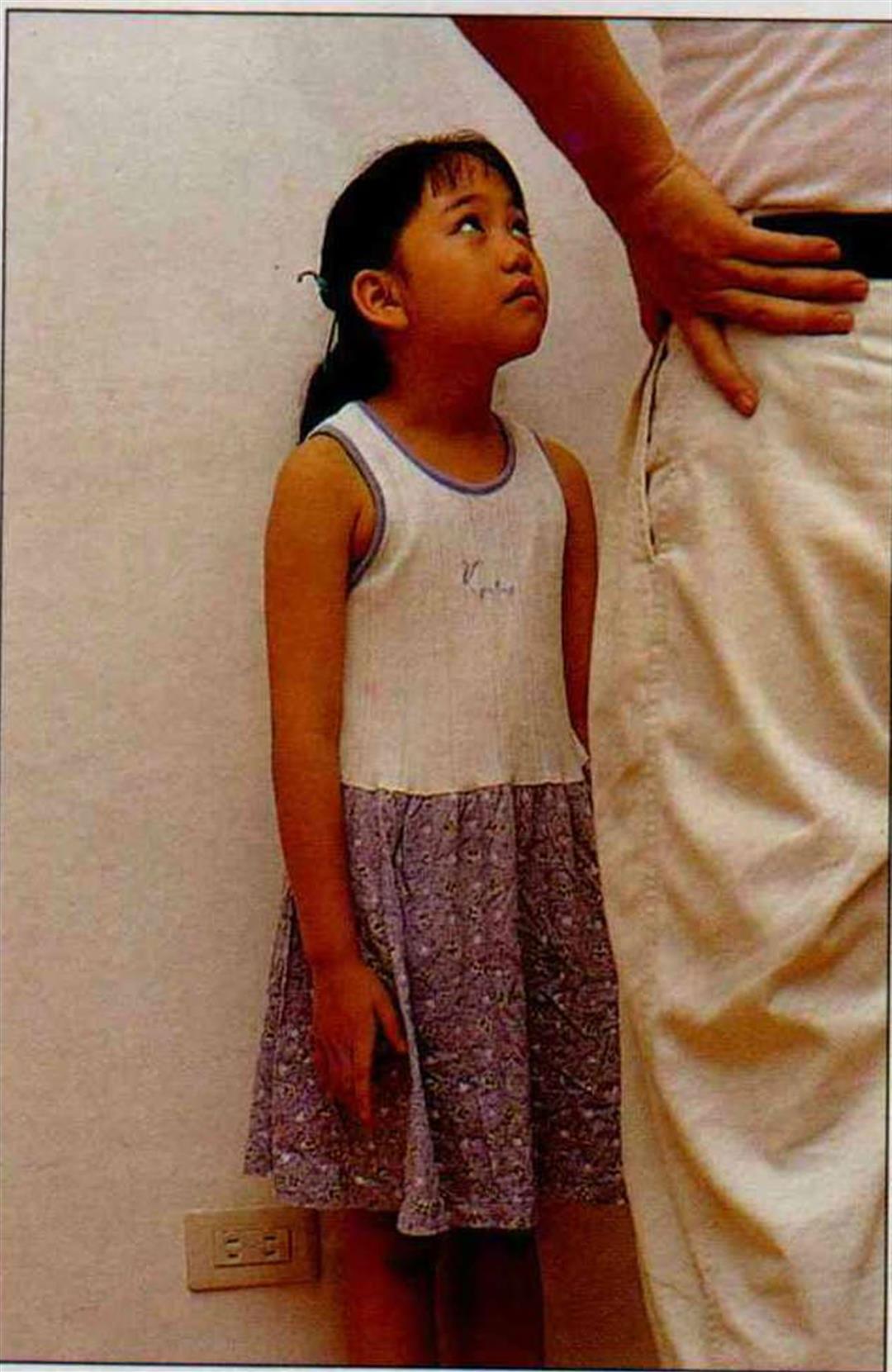

It is difficult for children to avoid mistakes. They need correction and guidance from their parents. This is another factor in Dad's EQ.

p.42

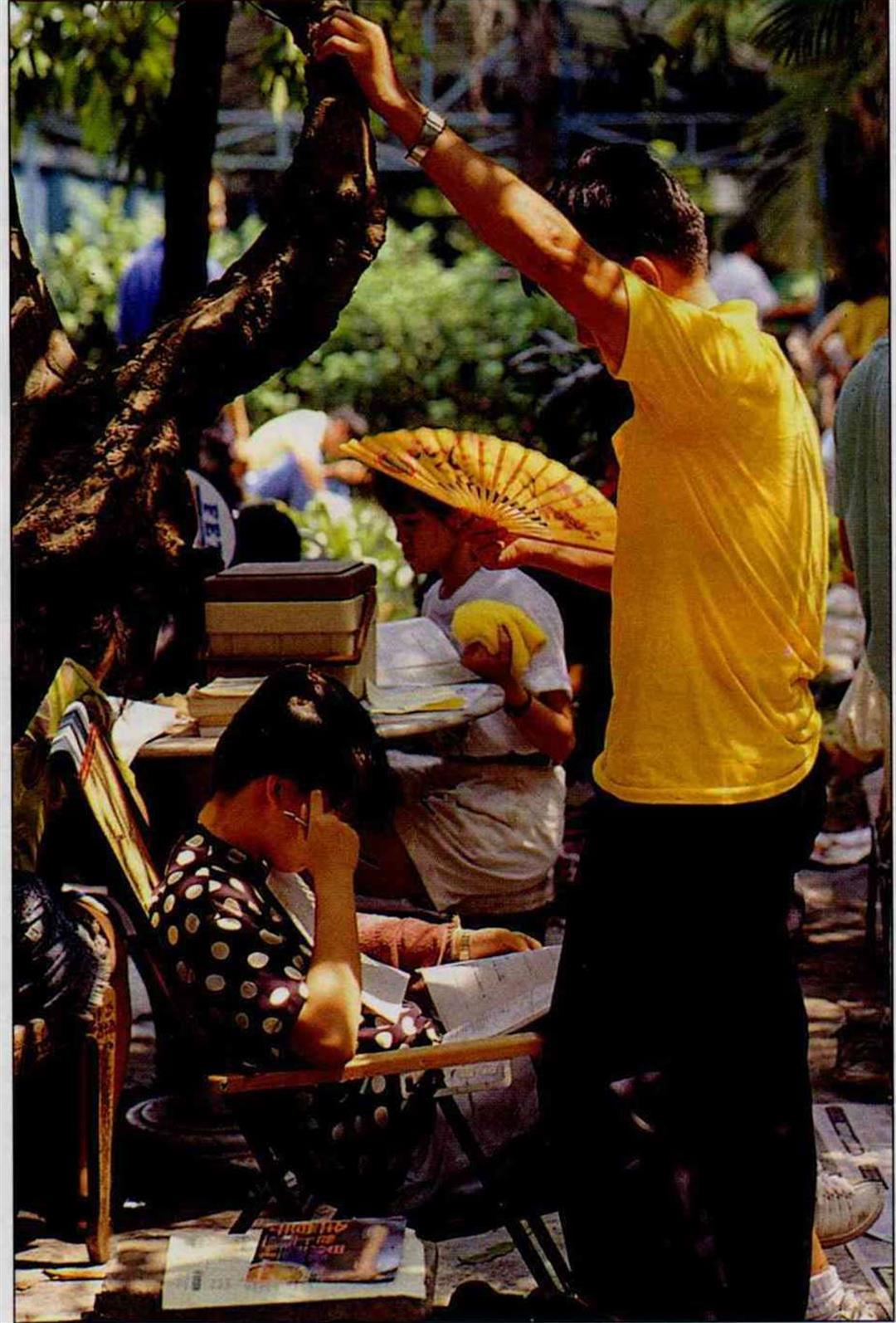

Accompanying children to entrance exams and helping them to bear the pressure to move on to the next level of schooling is the common experience of many of Taiwan's fathers.

p.43

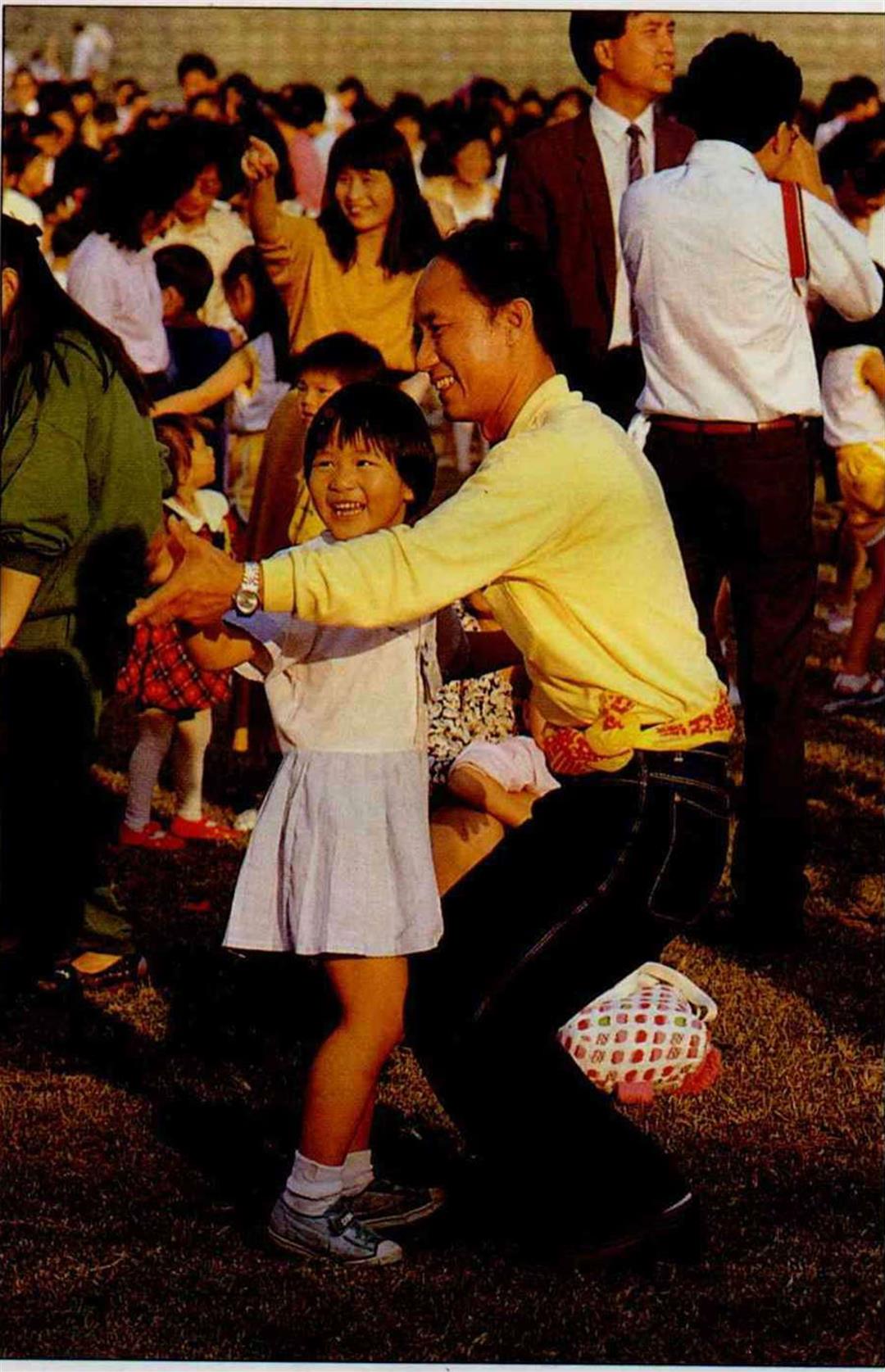

Many men have realized that accompanying children at activities is not a sacrifice of their time, but may, instead, restore their youth, creating a "second childhood."

p.45

There is no universally applicable pattern for parent-child relationships. But, if parents are willing to grow and learn with their family, they can experience a rare life process. (photo by Diago Chiu)

The modern division of parental roles tends toward having each parent do those things for which he or she has aptitude. There are many men who do housework with more delicacy than women. (photo by Huang Li-feng)

It is difficult for children to avoid mistakes. They need correction and guidance from their parents. This is another factor in Dad's EQ.

Accompanying children to entrance exams and helping them to bear the pressure to move on to the next level of schooling is the common experience of many of Taiwan's fathers.

Many men have realized that accompanying children at activities is not a sacrifice of their time, but may, instead, restore their youth, creating a "second childhood.".

There is no universally applicable pattern for parent-child relationship s. But, if parents are willing to grow and learn with their family, they can experience a rare life process. (photo by Diago Chiu)