After a late night of treating villagers, Labay Duoruo, a shaman of the Atayal indigenous people, finally gets to bed in the wee hours. In the morning, she is called out by her son-in-law on behalf of a woman whose husband has just died, and she is preparing to do a divination for this woman.

Asking the dead to rest

"I haven't been feeling well lately," says the woman. "I hope the shaman will help me find the reason."

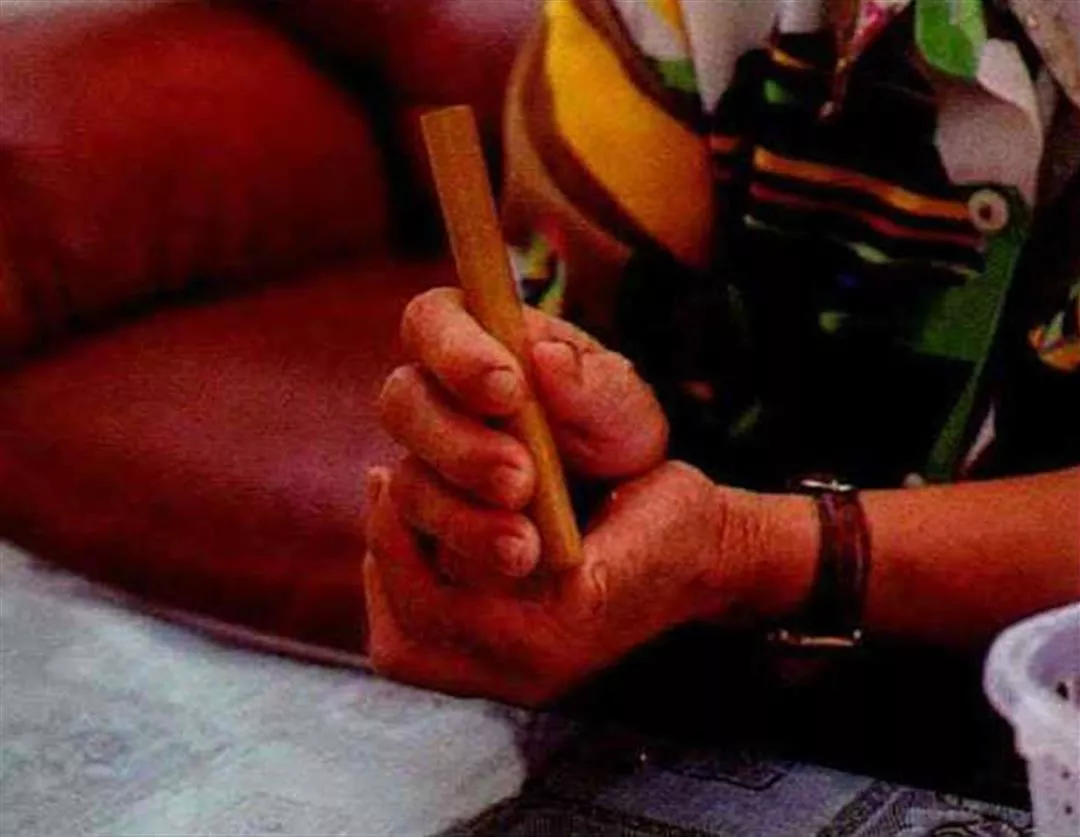

As she listens to the woman's request, Labay holds in her hand a bamboo tube about 10 centimeters long and one centimeter in diameter. The bamboo tube rests in the fingers of her other hand, and she rotates it continuously. Spinning the tube with great concentration, she asks the spirit of the shaman who in life was her mentor in the study of magic: "Is this woman ill for some reason related to the ancestral souls?"

Turning turning. . . . Suddenly the bamboo sticks in her fingertips, and will turn no more. Labay gives the tube a yank, and with a "pop" it comes off her hand.

"Your husband still misses you, and comes back to see you. You yourself have not let him go, and there are still too many things hidden in your heart," says Labay. "Go home, kill a chicken, and burn it as an offering to him, asking him to go on his way and not come back for you any longer."

After hearing Labay's instructions, the woman hurries home to kill a chicken, and starts a fire in front of her house; she then throws the chicken into the crackling fire. Later Labay goes to the woman's house, and takes a little bit each of the blackened chicken's head, wings, feet, and gizzards. She wraps these in a leaf, and hides them in a nearby bush, so that they will not be taken away by anyone. Then she digs a small hole next to the fire, and throws in four NT$1 coins, each representing NT$10,000. Finally she adds water and fills in the hole with soil; this is a gift to the late husband of the woman.

When the magic is complete, the woman says happily: "I feel much better already."

Ancestral souls by your side

Through instructions from "ancestral souls" (a blanket term covering the souls of all deceased tribal people) Labay is often able to resolve difficult problems for villagers. Yang Ming-hui, an Atayal teacher at the Chingmei Primary School in Hsiulin Rural Township who has been filming a documentary on Labay, explains that in fact an Atayal shaman is really more like a medium. She can only wait passively for people to come with questions, and then pass their inquiries on to the ancestral souls. In contrast, Puyuma and Bunun shamans can take the initiative. As Yang says, "For example, in a foot race, their shamans could cast a spell so that the fastest man was unable to move." In the past many Atayal and Ami people would not approach the villages of the Puyuma or Bunun out of fear of their shamans.

The shaman is the means by which indigenous people communicate with the souls of their ancestors. In their cosmology, although the spirit world is clearly separated from the human world, the two realms are still accessible to each other, and everything-from daily life to festivals to war-can be influenced by the powers of spirits and ancestors.

In the traditional beliefs of the Puyuma people, the spirit world is some distance away from the village in a place unknown to any human. From this place, ancestral souls could come in contact with the mundane world anytime. For example, before going out on a hunt, if hunters heard a sneeze sound, that was the ancestral souls warning them not to go. If they did not listen to the warning, and went anyway, the hunters would fall ill after their return.

The Ami people believe that all living things have souls. Wu Ming-yi, a professor at the Yushan Theological College, says this is reflected in the ceremonies, community politics, and property rules of the Ami people. For the Ami, life is inseparable from religion.

Under such belief systems, shamans who can communicate with ancestral souls and spirits are naturally important figures. This is especially so in locales that have not been exposed to modern medicine. It is difficult to trace the causes of most illnesses, and traditionally indigenous people saw these as a function of spirits or ancestral souls. This is why, explains anthropologist Juan Chang-jui, "Over time, the treatment of illness became the main job of the shaman."

Replaced by Western medicine

But reliance on shamans has been in decline since the late 19th-century, when Christian missionaries began introducing modern medicine into traditional villages.

Mona Wadan (Chinese name: Kong Chi-wen), a member of the Atayal indigenous people and also the director of the public health office in Kuangfu Rural Township in Hualien County, working with Cheng Hui-chu, has conducted a study of the rapidly disappearing indigenous medical culture. They relate that missionaries often used medical skill as a way to spread Christianity among the indigenous people. Then, the Japanese colonial government established clinics in every village, starting in 1914. Since WWII, the ROC government has been enhancing the medical facilities in mountain areas. Today, modern medicine is generally the first choice of indigenous people.

In the Ami indigenous village of Chimei in Hualien, for example, in the 1960s, before the widespread availability of Western medicine, nearly half of tribal members consulted shamans for illness. By the end of the 1960s, less than 2% were going to shamans, while the number seeking Western medicine rose from 40% to 70%. (The others sought alternatives like natural treatments, mediums, and Chinese medicine.) As Chien Mei-ling, a doctoral candidate in the Graduate Institute of Anthropology at Tsinghua University, wrote in a study, "Medical policy and medical efficacy are the main factors that affect what forms of treatment people select."

Under the impact of modern medicine, indigenous people now only seek out shamans when it appears Western medicine has no more help to offer, and they have no choice. Under such circumstances, shamans have themselves had to adapt to modern times.

When an ill person seeks out Labay, she first tells the patient to go to a doctor. Only if the patient has been unable to find a cure over a long period does Labay then conclude that the illness is related to ancestral spirits, and begin to do divination and magic.

"Alternative" treatments

Like modern doctors, Labay begins treatment by asking the patient questions to ascertain the patient's symptoms and habits. If she cannot find out the reason for the illness from these questions, she then consults the spirits, or asks the Creator of All Things to send a dream to her.

Once there was a minister who fell seriously ill. His family knew that Labay had helped a number of people in the village with her magic. Without telling the minister, they took some of his clothing to Labay. Amazingly, after she finished her magic, the minister, who had been on the edge of death, was able to get out of bed and move around, and even resumed his job of sending children to school and picking them up after class. The man was able to live for another month before passing away.

Then there was a case of an Atayal man who was in hospital, but didn't trust modern medicine, so he called Labay. Labay immediately asked the ancestral souls, and after getting a positive response, this Atayal person then felt at ease about accepting modern treatment. Juan Chang-jui says, Western medicine will tell patients that they have an incurable illness, but the shamans believe they can cure everything. Psychologically, shamans give people more confidence, and psychology can definitely affect biology.

Traditional medicine offers many functions that modern medicine still cannot duplicate. Mona Wadan and Cheng Hui-chu say that the advantage of traditional medicine is that it considers the impact of a person's entire social network. The key to treating an illness may lie in finding the tears in the ill person's social network, in order to restore the person's spiritual balance. For example, traditional medicine often ascribed illness to the breaking of the taboos, such as killing people, lack of filial piety, or theft.

Orthodoxy or superstition?

"There are still many illnesses that Western medicine cannot cure, so people still rely on traditional indigenous medicine," says Juan Chang-jui. Therefore, it is not a bad thing that shamans still are practicing traditional medicine. However, their spiritual authority has waned under the clash between new and traditional beliefs that has taken place over the last century, and there's been a sharp drop in the number of shamans.

Atayal teacher Yang Ming-hui says that when foreign missionaries penetrated deep into aboriginal communities to spread their religion, they condemned traditional beliefs as superstition. Thus, when many indigenous people accepted both the Christian God and modern medicine at the same time, they distanced themselves from traditional beliefs. In addition, there's a great population outflow from tribal villages, and even the languages are disappearing. Passing on the shamanistic arts is extremely difficult, and the aboriginal history and culture embodied in the shamans is at risk of disappearing.

"Indigenous people are adaptable by nature, and most of them don't feel any imperative to preserve traditional culture," says Yang. Labay feels that, given the diversity of options available to young people in modern life, and the declining functions of the shamans, it is completely understandable that no one wants to study the arts of the shaman.

The impact has been so widespread that, taking the Atayal in eastern Taiwan for example, there are only two shamans remaining among them-Labay, and a 100-year-old shaman in Nan'ao.

Ever-present ancestral souls

Yet, even as shamanism withers, there has been a change in the attitude of orthodox religion to shamanism as a growing number of indigenous people have themselves become ministers or priests. Equipped as they are with a much deeper understanding of traditional beliefs and culture, they by no means look down on the shamans.

Lin Ching-sheng, an Ami Presbyterian minister in Chi'an Rural Township in Hualien, says the meaning of life can be sought not only in Christian doctrine but in traditional beliefs as well. In the past, based on Christian doctrine, tradition was seen as superstition, aboriginal culture was rejected and traditional clothing burned. As an Ami himself, Lin feels that the two belief systems are not necessarily in conflict. For example, both stand in awe of the Creator of All Things, and both believe people have eternal souls. Moreover, in ancient times the Hebrews themselves communicated with God through priests. Thus tradition is not so much opposed to orthodoxy as it is parallel. Lin concludes: "Indigenous people simply have their own way of communicating with God."

Currently Lin is doing field research on the shaman system. He is also helping indigenous people rebuild confidence, and encouraging everyone to revive traditional clothing and traditional culture. He says, "Now virtually all the young people in the church share these same ideas."

As outside pressure has eased, the shamans have begun to see themselves in a different light. Besides being a shaman, Labay is also a baptized Christian. She accepts the belief that Jesus was sent to save the world, but at the same time she respects the ancestral souls. Though a little ashamed to admit it, she says she is often too busy to go to church.

Yang Ming-hui says that indigenous people's adaptation to Christianity is similar to how Chinese accepted Buddhism: They simply moved their ancestral tablets off to one side. Although indigenous people have accepted a foreign religion, traditional beliefs still have some of their authority.

Will do anything

The powerful Atayal shaman Labay, through instructions from the ancestral souls, is still helping village people today. In recent years even some Han Chinese and Ami people have come to ask this sole remaining practicing Atayal shaman for divination. Also, a number of scholars studying indigenous shamanism have paid visits to her home. Her son says, "Most of the phone calls at home are for her!"

Besides treating illness, Labay also uses her magic to help people find lost animals or objects. Once she was consulted by a family whose daughter had been missing for more than a month. Through divination, she told the family that the girl was safe somewhere in northern Taiwan, was not being controlled by anyone else, and would return on her own after while. As it turned out, just a few days before school began, the girl-having had enough fun-returned home to her parents.

The reliance of indigenous people on shamans, though no longer pervasive, is still reflected in the scope of matters that are thought solvable by magic. People have sought out shamans to inquire about much-missed distant friends, to get help conceiving a child, and to find out their chances with the object of their still-secret affections.

Mona Wadan, himself a practitioner of Western medicine, once went to an Ami shaman. He had been hoping for another child, and figured he had nothing to lose by trying. His wife Panay Mulu even declared in the course of giving an academic paper about shamanism that they owe their adorable young daughter, who is eight years junior to their eldest child, to the shaman.

From generation to generation

While a few shamans still operate, their numbers and functions have fallen dramatically. As the anthropologist Juan Chang-jui says, "It's not like the past, when the shaman had a high status and a good income in traditional villages."

Modern doctors have to pass exams to get into medical school, and study hard for many years before they can begin their professional lives. It is not easy to become an indigenous shaman either. One must be selected by the ancestral souls. Although one may go on her own to become an acolyte to a practicing shaman, there's no guarantee that she will "graduate" and win "certification."

Labay began studying to be a shaman in 1986. By that time, five of her ten children had passed away. She felt that this was some kind of punishment from the ancestral souls, and sought out a shaman to find out why her children had died young and also to find some peace of mind for herself. As Yang Ming-hui says, "The Atayal people believe that a child which has died young has been called back by the ancestral souls."

After receiving permission from a shaman, Labay spent four difficult years learning the shaman's secrets. With the support of her husband, Labay finally became a shaman in her own right. The day she completed apprenticeship, the shaman prepared chicken and pork as offerings to previous shamans in the line. Thereafter, he gave Labay a piece of rolled-up sticky rice through a bamboo divination tube. When Labay accepted the rice, this symbolized that the shaman had transferred to her all the magic powers of the line, and she thus became the eighth shaman in the succession.

"Usually," says Yang Ming-hui, "shamans will know their own destiny, and before dying, pass on their powers to a successor."

Unlike Labay, who decided herself to become a shaman, the Ami shamans from Tungchang Village in Hualien have no choice. It is believed that the ancestral souls will bring a serious illness down on the selected person, and only relieve this illness when the person agrees to study the shaman's art.

Chiu Chi-chien, an anthropologist who specializes in the ancient society and culture of the Bunun people of Taiwan, has written that a Bunun could voluntarily choose to learn the shaman's craft, or could be instructed by a shaman in a dream.

The last shaman?

At present, the communities which still have a fairly large number of shamans include the Bunun community of Sanmin in Kaohsiung, the Puyuma community of Nanwang in Taitung, and the Ami community of Tungchang in Hualien. But even their numbers are falling.

Panay Mulu, who is executive director of the Foundation for Aboriginal Music, Culture, and Education of Taiwan, and who has been studying Ami ritual music for more than a decade, takes Tungchang as an example. "Over the past few years, six Tungchang shamans have died, but only three new ones have entered the ranks. Now there are only 15 left."

Although in modern society it is inevitable that the number of shamans will decline, they have been after all a vital part of the culture of the earliest residents of Taiwan. Mona Wadan calls on people to restore traditional shamanism to a position of respect, and to make a written and audio-visual record of the shaman's craft.

Yang Ming-hui, who has been at Labay's side doing his documentary for three years, has the same sense of urgency about recording traditional shamanism and indigenous culture. Yet Labay herself is not anxious. Although she intends to pass along her mantle to her daughter, who is interested in the shaman's magic, Labay still feels very healthy, and is in no hurry to find a successor. Moreover, she declares, "My daughter is only 40 or so, so she needs more experience in life."

Until she finds a successor, Labay remains someone that many villagers depend on, and she's happy to use her abilities to help others. On a typical day, Labay goes first thing in the morning to the fields to tend the chili peppers and hemp she raises herself, and works until she has built up a good sweat. She explains: "It does a body good." Also, her nimble hands are skilled at weaving, and when she has free time she often weaves beautiful cloth with traditional patterns.

"This could be the mobile-phone case of a gangster chief." With this comment she makes the traditional cloth that she is weaving fit into a modern world-just as she does with her shamanistic magic.

p.121

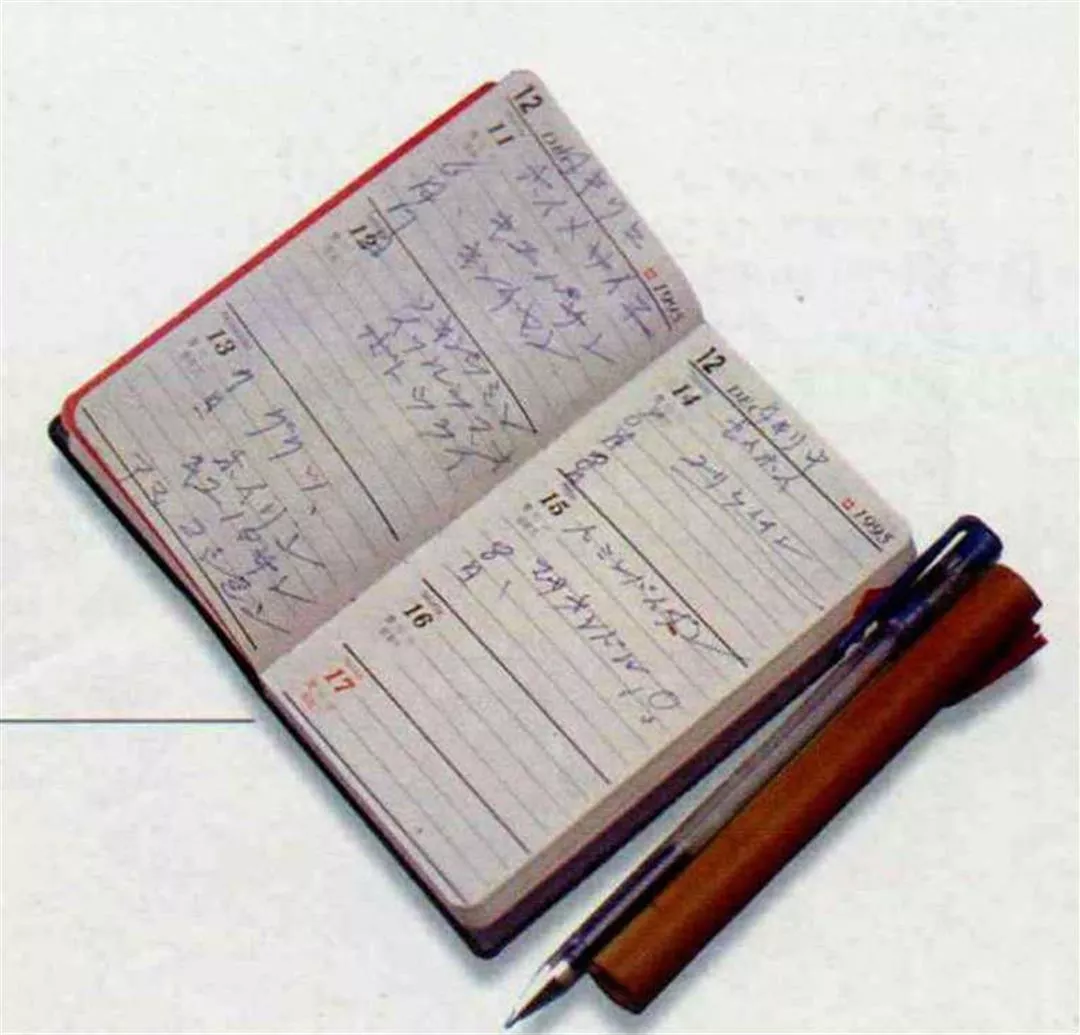

Labay's notebook is like a hospital patient's chart, recording the date of the first consultation and the symptoms reported; the bamboo tube is an important tool in her craft.

(opposite page) Labay, the last practicing Shaman of the Atayal indigenous people, prepares to burn a chicken as an offering to a departed soul.

p.122

Labay practices her shaman's art in a room which includes an image of Christ and a crucifix; she sees no conflict between her traditions and the new religion.

p.123

Labay turns the bamboo tube in her hand; when it sticks, that means the ancestral souls have answered her query.

After burning the chicken, she digs a hole and places in four NT$1 coins, each representing NT$10,000. The money is to send off the restless soul of a departed person and save the family from being bothered again.

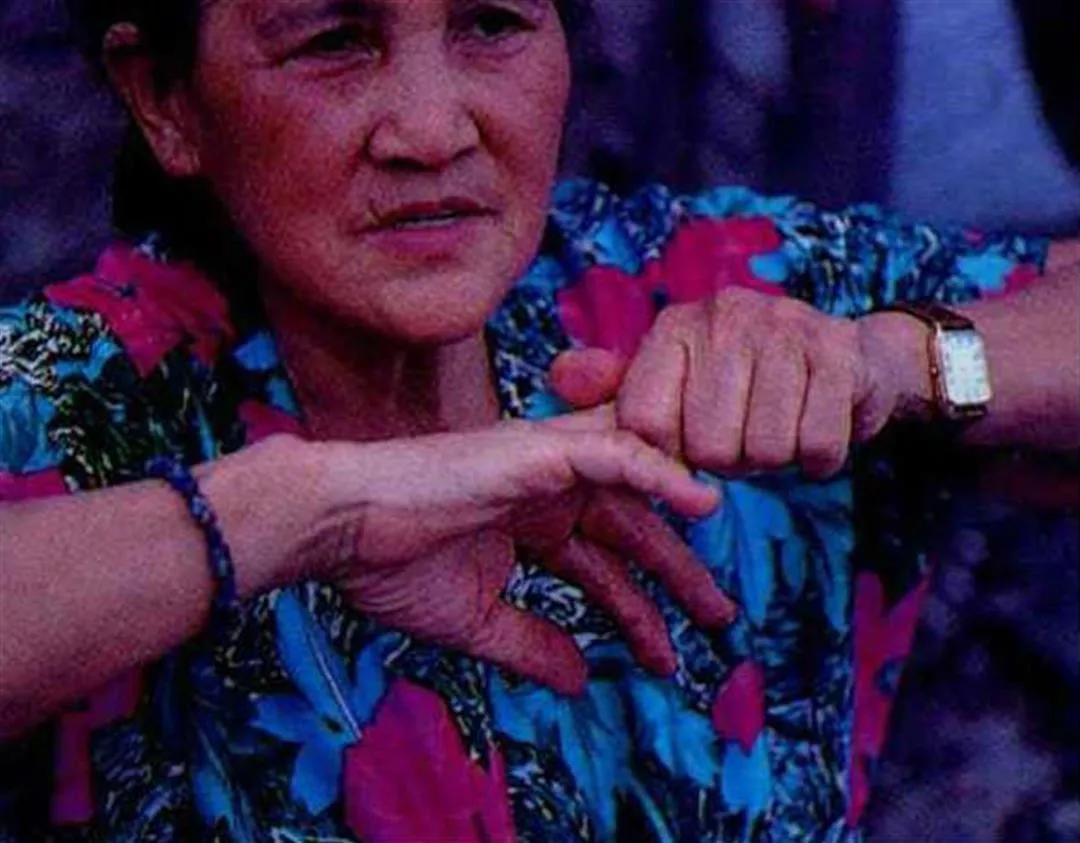

After completing her magic, Labay pops her finger joint, symbolizing the successful completion of the ritual: the departed will no longer haunt the living.

p.124

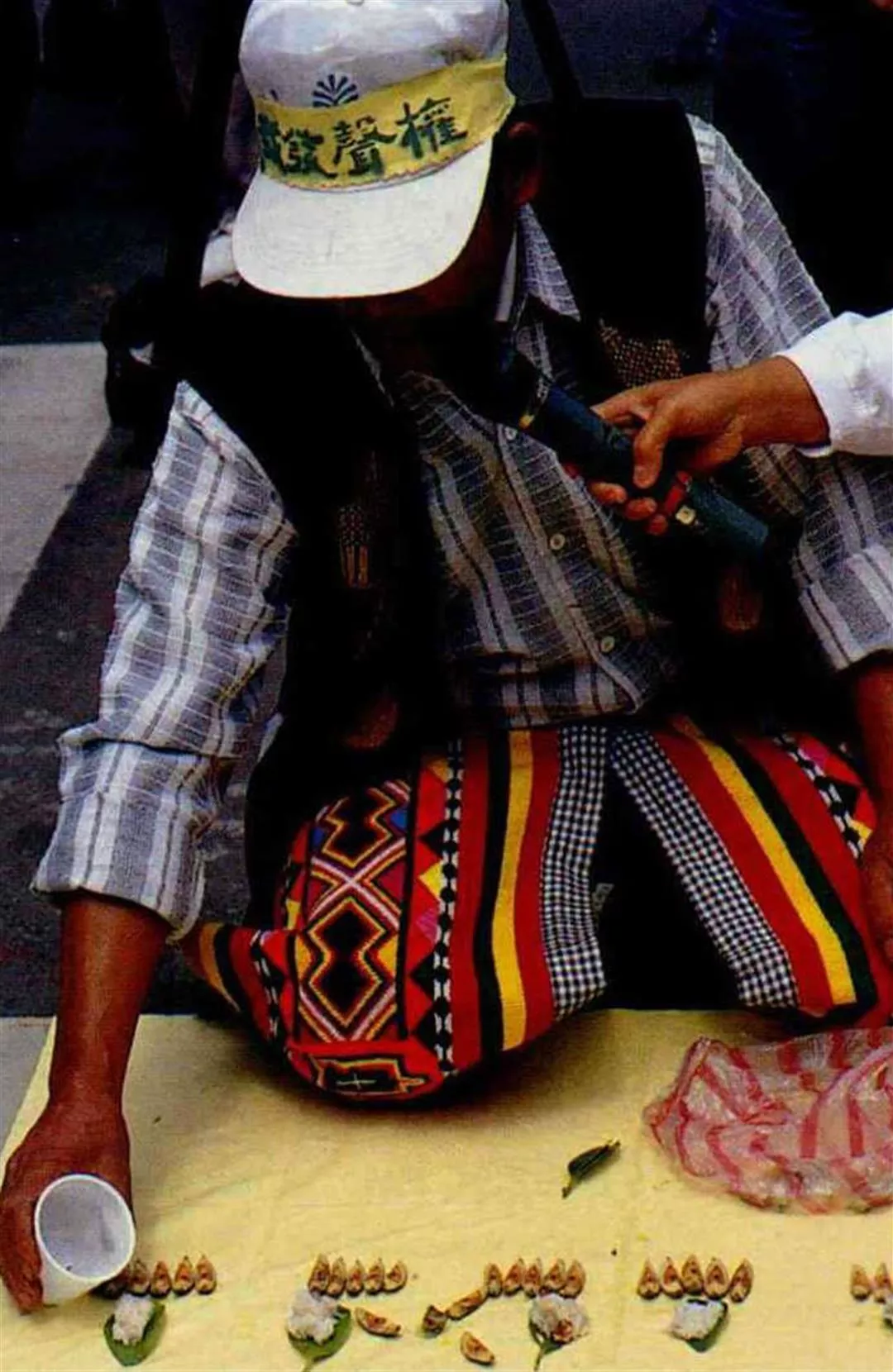

Betelnut is an important tool for Puyuma shamans. In 1997, as the Public Television bill languished in the Legislative Yuan, a Puyuma shaman was invited to the Legislative Yuan to try to help the forces of good; soon thereafter, the law passed without difficulty. (photo by Pu Hua-chih)

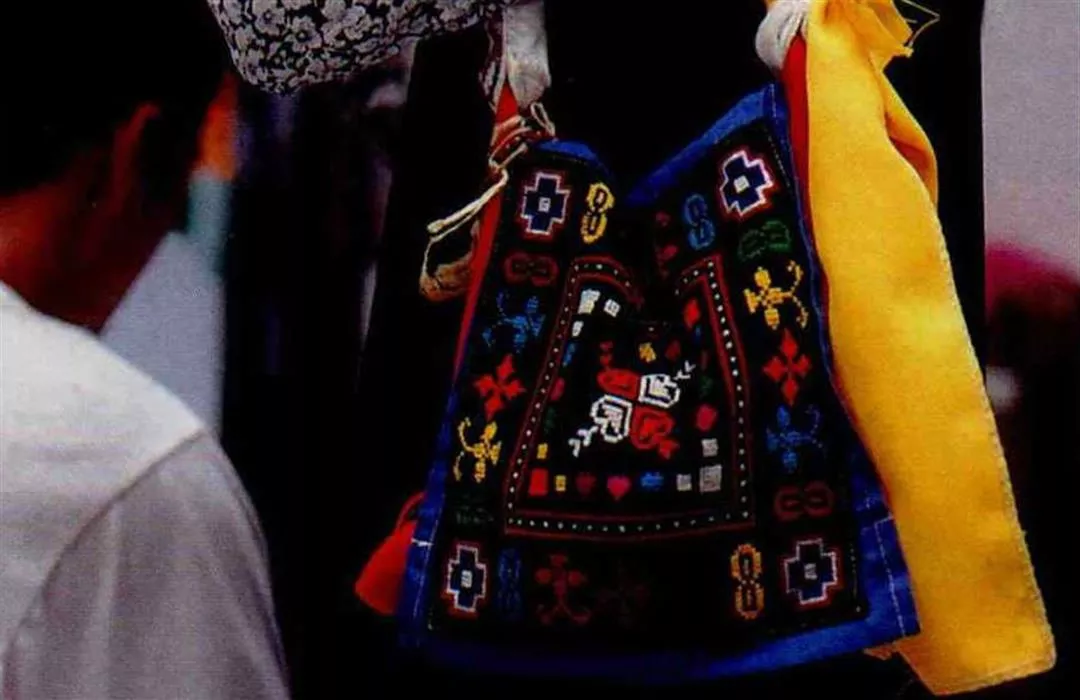

This blue embroidered shaman's pouch, whose strap is decorated with yellow strips of cloth and glass beads, contains betelnuts, a small knife, and other tools of the trade. Puyuma shamans make a new one each year; they are not supposed to be touched by outsiders.

Among the nine aboriginal peoples, the Puyuma are reputed to have the most powerful shamans.. Each has a spirit house. The photo shows the asap grass hung by the shaman each year; its aroma is supposed to draw out the ancestral souls.

p.127

Labay's weaving skill has not been made obsolete by modernity; the same could be said of her shaman's skills.

Labay's notebook is like a hospital patient's chart, recording the date of the first consultation and the symptoms reported; the bamboo tube is an important tool in her craft.

Labay practices her shaman's art in a room which includes an image of Christ and a crucifix; she sees no conflict between her traditions and the new religion.

Labay turns the bamboo tube in her hand; when it sticks, that means the ancestral souls have answered her query.

After burning the chicken, she digs a hole and places in four NT$1 coins, each representing NT$10,000. The money is to send off the restless soul of a departed person and save the family from being bothered again.

After completing her magic, Labay pops her finger joint, symbolizing the successful completion of the ritual: the departed will no longer haunt the living.

Betelnut is an important tool for Puyuma shamans. In 1997, as the Public Television bill languished in the Legislative Yuan, a Puyuma shaman was invited to the Legislative Yuan to try to help the forces of good; soon thereafter, the law passed without difficulty.(photo by Pu Hua-chih)

This blue embroidered shaman's pouch, whose strap is decorated with yellow strips of cloth and glass beads, contains betelnuts, a small knife, and other tools of the trade. Puyuma shamans make a new one each year; they are not supposed to be touched by outsiders.

Among the nine aboriginal peoples, the Puyuma are reputed to have the most powerful shamans.. Each has a spirit house. The photo shows the asap grass hung by the shaman each year; its aroma is supposed to draw out the ancestral souls.

Labay's weaving skill has not been made obsolete by modernity; the same could be said of her shaman's skills.