When you think about xiang sheng performances--traditional shows in which two people carry on quick, funny back-and-forth banter--several representative voices will probably float into your mind. For the last 30 years, the series of cassette tapes put out by the two "old Pekinese" Wei Lung-hao and Wu Chao-nan have entranced listeners over and over again, to the point that as soon as one phrase is finished, they know what the next phrase will say.

In terms of innovations, everyone will think of the debut play put out by the Performance Workshop ten years ago, "That Night, We Laughed." Strictly speaking, it used theater to display the charm of xiang sheng dialogues. Composed of five acts, and displaying no elaborate backdrops or lighting, it relied on the fame of the actors and the allure of traditional dialogue shows, whose give-and-take gab is cute and cunning and hip to the events of the day. Up and down the island of Taiwan, the workshop put out more than 20 performances, each packed to capacity. Men and women, kids and old folks alike were all swept off their feet.

Raising comic dialogues from the dead

As all that uproarious laughter was going on, many people earnestly asked director Stan Lai, "How did you revive comic dialogues?" At the time he felt that dialogue shows were dead. The concept behind his play was to stimulate people to reflect upon tradition through a form of performance art which has been forgotten by the times. Little did he expect that this "comic dialogue theater" would inadvertently infuse a breath of life into comic dialogue. It not only ignited the interest of the public, but also prompted many xiang sheng fans to gradually establish their own performance groups. Ever since, the old canon of dialogues has been heard more and more often in open public spaces and teahouses. And some people have begun to create new dialogues. Feng Yi-kang of the Shining Sound Workshop says, "It's like--whoosh!--you've opened the lid of a crock pot, and everyone's just rushed forth."

Although they have stirred up no wild sensation, a small number of professional troupes have been in circulation during the last ten years. Dialogue shows are in fact far from extinct. A set schedule of public performances will rarely "set the world on fire," but because of the shows' flexible structure of two roving performers, troupes are frequently invited to perform for organizations or schools, or to make an appearance at New Year's banquets and other such functions. The cassette tape market has proven to be even more popular, year in and year out.

In the face of social change, actors do not feel constrained to wear the ceremonial mandarin long gown (changpao) and jacket (magua). Western-style clothes are okay. And the once-obligatory painted fan is no longer necessarily in their hands. As for dialogue content, in addition to those traditional scripts that still sound fresh after a hundred listenings, some people have begun to offer up new creations in step with current times. And the language employed is no longer Beijing Mandarin with its heavily retroflexed consonants. In recent years, comic dialogues have imperceptibly gone through an unprecedented metamorphosis--they are now often recited in local dialects.

Beijing the birthplace

Ten years ago, the Hanlin Folk Arts Story-Telling Troupe began experimenting with Taiwanese-language dialogues. Their current repertoire includes dialogues in Mandarin, Taiwanese and Hakka, and they adjust their program according to the most commonly spoken dialect of the performance locale. For example, in March of this year when they put on a show in the Hakka stronghold of Miaoli, they featured Hakka dialogues. As for exclusively Taiwanese dialogue shows, look no further than the comic team of Ah Pao and Ah Kiao and their "Taiwanese Xiang Sheng--Tapcuiko." Five years ago in Tainan they performed "Customary Life," poking fun at the customs of that great event in life--marriage--and offering up a host of comic commentary on everything from meeting one's prospective mate to throwing an outdoor banquet. And that was not enough: In March of last year Tsai Ming-yi (a.k.a. "Ah Pao") and Feng Yi-Kang performed a dueling dialogue of Mandarin and Taiwanese, called "Xiangsheng vs. Tapcuiko."

All right, all right... All these terms are bound to be perplexing. When they talk in Taiwanese, is that "Taiwanese xiang sheng"? And what is "tapcuiko"?

In its original form, xiang sheng referred to the form of comedic opera developed in Beijing. Today it has over 100 years of history. Other regions of mainland China have similar performance traditions, such as huaji farces in the Shanghai dialect or the lachang opera of northeast China. Although they are not identical in form, all of them have sprung up from homegrown native-dialect comic performances.

Spicing up proper Beijing Mandarin with a dash of humor in a local dialect is nothing shocking or unheard-of. This technique, called qiekou huar, frequently draws upon miscommunications between different dialects brought about by mispronunciation or hearing the wrong word, and through mutual mockery or sarcasm, causes people to reflect upon themselves.

Laughin' it up in Taiwanese

Wei Lung-hao, of the older generation of comic dialogue performers, was of the opinion that if xiang sheng were to be performed in Taiwanese, then it would be better to give it a different name. Several years ago, he thought of the phrase kongqiu ("talk laugh"), but when he tried to "translate" the original xiang sheng dialogues into Taiwanese, some Mandarin humor, such as interesting homonyms, disappeared.

Furthermore, comic dialogue by its very nature demands close attention to oration (of poems, tongue twisters and jokes), imitation (of various regional dialects, insect noises and bird calls) and singing (folk ballads, regional operas, and even pop songs), all bound up in a comical style. The two performers, one funny and one straight, must both have a base in Peking opera, so that their chatting will have a lilting, musical feel and a distinct rhythm.

Taiwanese is by nature a language of daily life, with lively and interesting phraseology. "If you use the posturing and tone of Pekinese xiang sheng to perform Taiwanese dialogues, it would be absolutely out of context. It would sound uncomfortably strange," says Tsai Ming-yi.

Are there, then, any similar forms of performance in traditional Taiwanese-language culture? For some people, tapcuiko comes to mind. This was originally a contest of wits that the common folk took part in when relaxing and chatting. At a bit more sophisticated level it is called sikulian, or "four line responses." Two people trade statements four lines in length, each answering the other's previous reply. The goals are verbal parallelism and rhyme; it offers a strong poetic appeal. An example is, "The new bride's been married into our house/ The family prospers every year/ This year we've got a daughter-in-law/ Next year we'll build a big house." The Hakka dialect also has a form of tapcuiko (called dazoigu), which also arose from a long tradition of neighborhood gossip.

Name-brand imitation

Tsai Ming-yi believed that the structure of the "four line responses" was too rigid, making it difficult to fit in interesting comments. So he experimented with blending tapcuiko and xiang sheng together, preserving on the one hand the former's argumentative flavor, while adding the latter's comedic rules and techniques. He created what he calls a "fraudulent name-brand imitation"--"Taiwanese Xiang Sheng--Tapcuiko."

When you listen to it, Ah Pao and Ah Kiao's performance seems as natural as two people involved in an informal debate. For example, "Introducing the Bride and Groom" features this kind of conversation:

"Come on, are you arranging a meeting between the bride and groom or a New Year's feast?"

"Whenever we Taiwanese do anything, we have to serve up a bunch of food, and of course we love to discuss the preparations in advance."

"Yes, yes! And what did you finally decide?"

"In the end, my mother made the final decision."

"What was that?"

"To throw a dinner in the street!"

Five years ago, their show "Customary Life" was included in the National Theater's Experimental Theater Series, and in an instant, it became exceedingly popular. Seven or eight recording companies looked into the possibility of making an album. All at once Tsai Ming-yi found himself in this new world; there were even listeners who wrote him letters encouraging him to write some eloquent passages of Taiwanese, so that their children could learn Taiwanese in a relaxed setting.

Where Mandarin and Taiwanese mix

And how is mixing Mandarin and Taiwanese a "pioneering effort"? At the outset, this was the playful work of Tsai Ming-yi and Feng Yi-Kang. They took a number of works from their original contexts and pieced them all together, mixing and matching half in Mandarin and half in Taiwanese. In the resulting creation that spontaneously fell into place, they played the roles of the ancient general Xue Pinggui and his loyal wife Wang Baochuan.

Tsai Ming-yi sang the part of Xue Pinggui in the style of gezai Taiwanese opera, and Feng Yi-Kang sang the part of Wang Baochuan in the style of Beijing opera, first throwing back and forth several jokes involving inter-dialectical miscommuni-cation. Pinggui would say in Taiwanese, "My body was captured by the barbarian hoards, but my heart has stayed with the Tang [pronounced deng in Taiwanese, which also means sausage]." Baochuan would then ask in Beijing Mandarin, "Are you bringing me a letter from my husband?" This sounds like "Are you bringing a driver?" in Taiwanese. Xue Pinggui can't help being confused.

Then, with one of them playing a Taiwan beau, the other playing a mainland lass, they start singing together "Pinggui Tricks His Wife." Are they trying to imitate the reunion of an old married couple who have been separated for 40 years? Or a love affair between people from two different places that has happened after relations between Taiwan and the mainland warmed up? This comic dialogue opened a great number of possibilities. But then they did not continue to develop it.

The experiment was so novel that one couldn't help wondering, were they trying to bring about a comic dialogue "revolution"? On the contrary, they both tell the same story--this method "isn't revolutionary at all, and it's not too immense a concept, because it's actually the kind of language-mixing game that people play in everyday life." It's only that this innovation needs more polishing before it is mature.

Tools for mother-tongue education

Wang Chen-chuan, director of the Hanlin Folk Arts Story-Telling Troupe, takes a market perspective. The troupe went to the countryside to perform several times, but it seemed that the local audience didn't understand their language. There was no response from the audience. "It was a terrible fiasco." Afterwards, they began to perform xiang sheng in Taiwanese. The first time, the story was about a foreign preacher inviting over a Taiwanese interpreter to help him deliver a big sermon. The humor of language misunderstanding was thus unveiled. For example, "Today I've come to preach [bodao] in this honorable [gui] place" was interpreted as, "Today I come to this ghostly [also pronounced gui] place to spread rice shoots [also pronounced bodao]." After this, "As long as we perform in Taiwanese, the results are good," observes Wang Chen-chuan.

Not only adults but also kids have started performing xiang sheng in Taiwanese. Chen Ching-sung has been encouraging children to learn comic dialogues for over a decade now. When he first became infatuated with xiang sheng, he was originally looking for a way to remedy his "Taiwan Mandarin." One of the main goals of the Paoshih Children's Spoken Art Troupe, which he manages, is to teach kids to speak standard Mandarin. In the last two years, primary schools have begun to hold classes in the students' mother tongues, and ever since, comic dialogue performance has been swept along by this trend. It has started using the appeal of performance to entice children to learn their own local language.

Starting last year, the Taipei City Children's Comic Dialogue Tournament, sponsored by Paoshih, added a category of local language competition. Some children slowly entered the stage reciting Taiwanese verses. Some even quoted vulgarities on-stage. Nevertheless, "most kids cannot speak Taiwanese very fluently, so they end up saying a lot more funny things," says Chen Ching-sung. This year's competition will be divided into two separate categories of Mandarin and Taiwanese. The famous teller of ancient stories Wu Lo-tien will also give lessons to teachers. Some people predict that the number of participants in the Taiwanese category will grow more and more.

Meticulously processed "chit-chat"

Whether comic dialogues are done for commerce or as a game, or even for the mission of spreading native Taiwanese, this wave of local-dialect comic dialogue may be a reflection of the sudden popularity of native culture in Taiwan society over the past few years, or even of the political effect of integration among the several different ethnic groups.

Because the art form is new, people must determine the rules of the game before the structure of the new dialogues is set in place. For example, with the same responsive interaction and sharp interplay, what is the difference between Taiwanese xiang sheng and the talk shows commonplace in restaurants or on cable TV?

Director of the Taipei Musical Theater Troupe Liu Tseng-kai holds the view that this is a question of depth. "On the surface it looks like chit-chat, but who can't hold a conversation? How come two people can stand out and perform in front of the public? Because they chat in an interesting way." Feng Yi-kang says, "It has been meticulously processed."

Generally speaking, comic dialogues have a theme, and they are tightly structured. The key point of xiang sheng is nourishing "the bundle." This so-called "bundle" is the punch-line. When performing, the actors wrap up the funny statement, then through various techniques, they unveil it, bringing the audience surprising feelings that make sense in the context. This is called "shaking open the bundle."

The most common form is "responsive dialogue." Usually, one person is the main speaker, who is responsible for throwing out the punch lines. The other one lends support. The main speaker goes all out to be funny, and the "straight man" props him up. Otherwise, the two will be equally humorous and engage in a combative exchange. Don't belittle the supporting speaker; he has to take charge of the performance's rhythm and ask questions on the audience's behalf. According to the old rules, he is usually a senior in the profession, or even the master of the main speaker.

In comparison, the garden-variety talk show you might encounter in restaurants or on video tapes is loosely structured. The performers speak what they think. Some partners even gain an advantage through cruel words and lewd language.

Today's creations, tomorrow's traditions

Currently, many of the Taiwanese or Hakka comic dialogues are directly translated from Mandarin xiang sheng. Wang Chen-chuan admits frankly that his comprehension of Taiwanese is still limited. The series of local-dialect dialogues put out by the Hanlin Troupe up to now are all translated from Mandarin. But then, not every sentence can be literally translated. For example, the Beijing expression "People move to live, but if you move trees they die" can only be transformed into the Taiwanese idiom, "People have to work, chickens have to peck."

But Tsai Ming-yi believes that to promote comic dialogue in Taiwanese, it is not good enough to simply translate Beijingese or Taiwan Mandarin into Taiwanese, nor to simply tell a few Taiwanese jokes. They should develop new scripts, and introduce Taiwanese folk customs and history. "Otherwise, I might just as well do restaurant shows. Why should I exhaust myself like this?"

Indeed, comic dialogues have the function of documenting folk customs. Like musical dramas, comic dialogues have set scripts (duanzi). About 200 scripts have survived from the past. The more familiar ones are "Accents South and North," "The Manchurian-Han Banquet," "Eight Screens" and dozens of others. Most are created with operatic melodies, place names, rhythmic idioms, mistranslations and puns, rhymes or slang. For example, "Throwing a Charity Banquet" borrows from the custom of philanthropic families distributing gifts to the poor to record all the kinds of foodstuff wealthy families ate during the three big festivals of the year, and serves as a document of folk customs.

Tsai Ming-yi says he is not familiar with many of the old Taiwanese proverbs, so he created his own modern slang. His principle is to be lively, because "new things follow the times, and new phrases are always popping up." The scripts he has written include the hot topic in office life--"Sexual Harassment"--as well as "Any Votes for Sale?" which satirizes the peculiar state of affairs in Taiwan's electioneering process. Perhaps the creations that reflect the events of today will become the traditions of tomorrow.

Chen Ming-jen, a strong advocate of the Taiwanese-language movement, thinks that Taiwanese-language comic dialogue should put an emphasis on the fun of Taiwanese itself. Even introducing ancient customs should bear relation to modern life. "Interpreting past customs with modern concepts, rather than just reminiscing, will bring them back to life."

Don't deepen linguistic misunderstanding

The Hanlin Story-Telling Troupe's trademark performance in Taiwanese, "Selling Snakes in Snake Alley," is an example of a realistic portrayal of modern life. They imitate the nightmarket peddlers selling snakes and tonic medicine and even add a female figure who coquettishly sings, bringing the nightmarket ambience to life.

However, people have different ideas about the result. Some people think that it bubbles with vitality. Others disagree, wondering if they only bring a section of life onto the stage without any alterations and all they speak is everyday vulgar Taiwanese, will it strengthen the language prejudice that some people have?

"You have to be appropriate when cracking jokes about language. If the jokes are misunderstood, they will have unintended consequences, and increase conflicts," says former World College of Journalism and Communication broadcasting department director Tien Shih-lin, a winner of the Spoken Arts Heritage Award and long-time advocate of the oratory arts.

For example, the Hanlin Troupe's Hakka comic dialogue "Not Necessarily" (in fact, translated from Mandarin), which discusses the enigmatic differences between appearance and reality, is in rhythm with the pulse of society. For instance:

"Those with long hair are not necessarily women."

"People who shave themselves bald are not necessarily men."

"Going to a sauna does not necessarily mean you're going to take a bath."

"Going to a 'meat market' doesn't necessarily mean you're going to eat beef."

After the format is established, they can alter it at any time, depending on the social conditions, such as during the recent election campaigns:

"The person elected president might not necessarily be Taiwanese."

"The person that's elected might not necessarily be a monk."

"The person that's elected might not necessarily be a foreigner."

"Huh? Why do you say that?"

"Someone might have dual citizenship."

They have received invitations to perform this dialogue in some Hakka communities, and audiences feel very close to them. But one of the performers, Hsieh Hsiao-ling feels they are only starting, and they haven't been able to speak Hakka that fluently. She hopes she and her partner both can put more effort into collecting Hakka dazoigu, and finally they can create their own works.

Short yet sturdy

The change of language is certainly a selling point, but whether or not the content of comic dialogues can express the characteristics and humor of languages is also another important factor. Different dialects are easy to learn, but good scripts are hard to compose. And it takes quite some talent to make people laugh after they've heard a dialogue over and over again. Maybe we can say that if a dialogue touches on real life, whatever language it utilizes will sound good. On the other hand, using sensationalism to draw a big crowd, and resorting to base jokes, will only sabotage the art.

Comic dialogue is a short yet sturdy art form. Its format is simple, and the language it employs is also straightforward--everyone can understand it. And it can reflect the lives of the people in all their myriad aspects. It can draw on a wide spectrum of subjects, from astronomy to geography. The topics that are hot in the streets, the latest news, and events from the past can all be jabbered about in a relaxed and funny tone, and strike the chords of people's real concerns. Audiences can appreciate the content and can have a lasting and pleasant impression. That's why when other forms of spoken-word art are in a state of decline, comic dialogues can still attract attention and make people laugh.

Ever since the communists took over mainland China in 1949, they ignored most traditional arts, but they treated comic dialogues as a sharp weapon of propaganda, developing it far more than other forms of performance. In his "Essays on the Art of Comic Dialogue," the famous xiang sheng artist Ma Ji expresses the view that "xiang sheng is a powerful weapon to praise the new society, as well as to satirize old things and old thinking." Also because of its plain language, it can "reach deep into factories and academic institutions."

Rebellious art

As opposed to the political service comic dialogues perform in the mainland, the Pekinese xiang sheng master Wei Lung-hao believes that in Taiwan they can broadcast the voice of the middle and lower classes. Fundamentally, it is a "rebellious art." Actors should be like woodpeckers, pecking for insects in every tree; they should touch on the maladies of the time. He laments that people in power don't have the tolerance to accept satire, so they don't care about the spoken arts at all.

Is that really the case? Wang Chen-chuan feels that a bright future lies ahead, because politics is opening up now. "There are no taboos in the environment." People are in great need of funny flavoring to spice up their lives.

In fact, satire is the soul of comic dialogue. Whether it be criticizing politics or reflecting upon the life of the common people, it should be "funny but not cruel." The series of comic dialogue dramas put out by the Performance Workshop made a slapstick of certain parts of modern Chinese history, which filled the auditorium with uproarious laughter, but also an air of sadness. The performances we see currently, however, are mostly traditional scripts, or new scripts wrought in the mainland with "cosmetic makeovers" in Taiwan, but they rarely satirize current events. As for the younger generation, people like Feng Yi-kang and Tsai Ah-pao are very dedicated to the art form, but only time will tell whether their works will prove to be humorous and long-lasting, as well as perspicacious.

Old comic dialogues don't die

"Comic dialogues have a huge potential audience. It's hard to encounter people who don't like comic dialogues, isn't it? Who doesn't like being amused?" comments Liu Tseng-kai. But seeking out and cultivating these potential aficionados, and securing a position in this colorful "age of entertainment" will almost certainly depend on the efforts of devotees.

Feng Yi-kang recalls, "One time, I was on the stage with Li Li-chun performing 'That Night, We Laughed' and all of a sudden I had a moment of enlightenment. I realized that it wasn't important to worry whether comic dialogues live or die. So, I shed off my old mentality, and the space for performance was unintentionally widened. As long as comic dialogues are alive for one day, I'll do my little bit for them." Feng says he doesn't have the sense of mission to protect a unique cultural heritage, nor does he carry a burden for reviving traditional art.

Currently comic dialogues performed in local dialects are in the ascendant. If the trend keeps going like this, following Taiwanese and Hakka, maybe some day someone will perform comic dialogues in one of the aboriginal languages.

Actually, no matter what language is used, some sorrows and joys, loves and loathings--from the traffic and environment to the volatile political situation in the Taiwan Strait--belong to this era and to this land and are shared by all the people. If through this art for the masses, we can have a good laugh at the happenings of our time, salutary and inauspicious alike, will we be able to breach the barriers of language and achieve a new level of ethnic integration?

Let's hope comic dialogue performers can make lively use of this short and sturdy art form to crack some good jokes, as well as develop "new wine" while they polish an "old bottle."

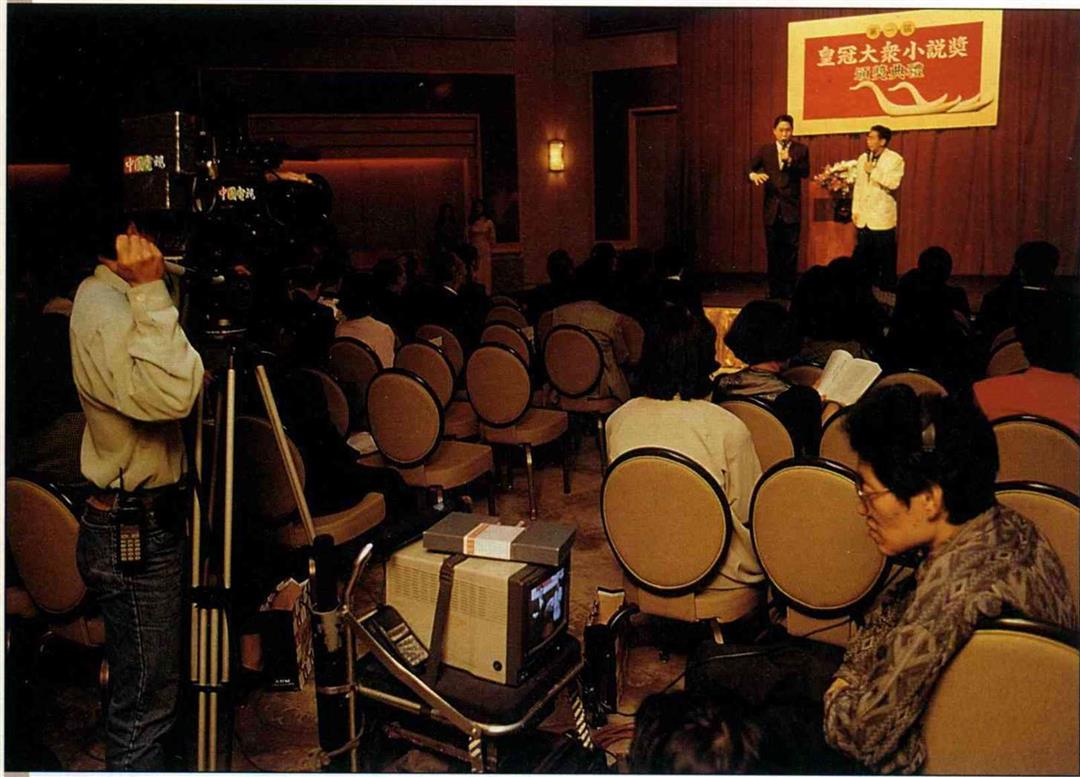

The two roving performers of a xiang sheng act are known to make an appearance at many organizations' events. When The Crown magazine held an awards ceremony, they invited the Shining Sound Workshop to do a dialogue about the topics featured in the nominated stories.

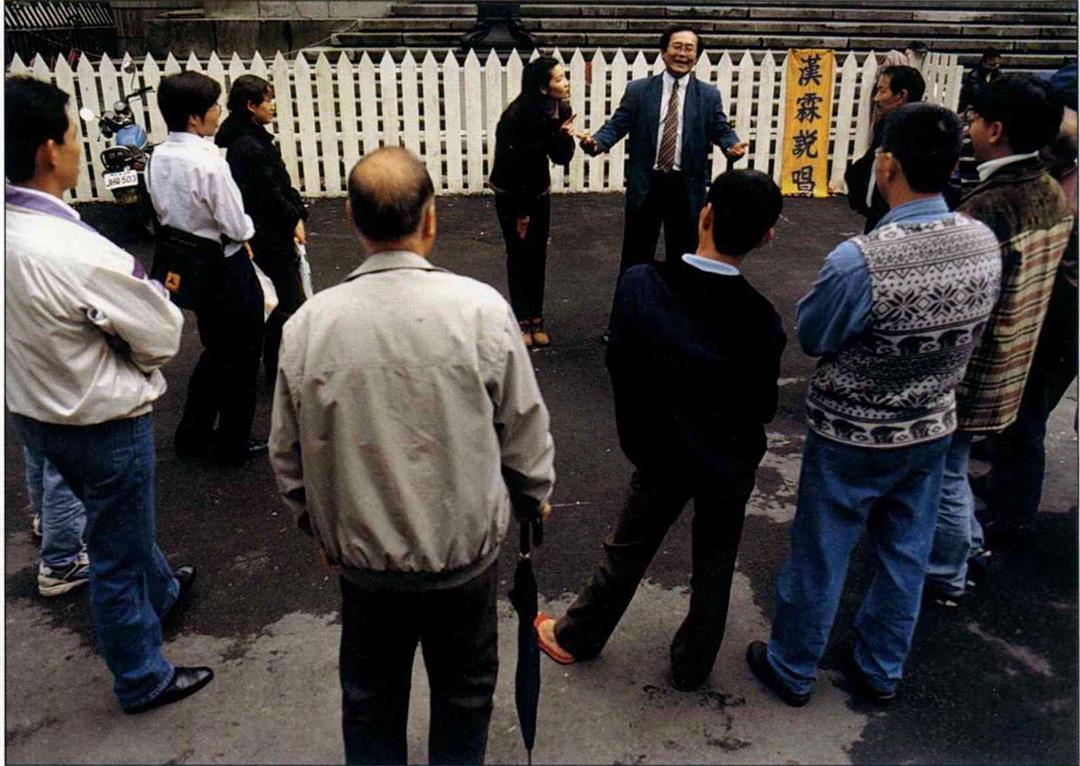

Comic dialogues use laughter as a weapon, satirizing the peculiar phenomena of society. These actors standing on the side of the street joke about the hottest current events to bring smiles to listeners' faces.

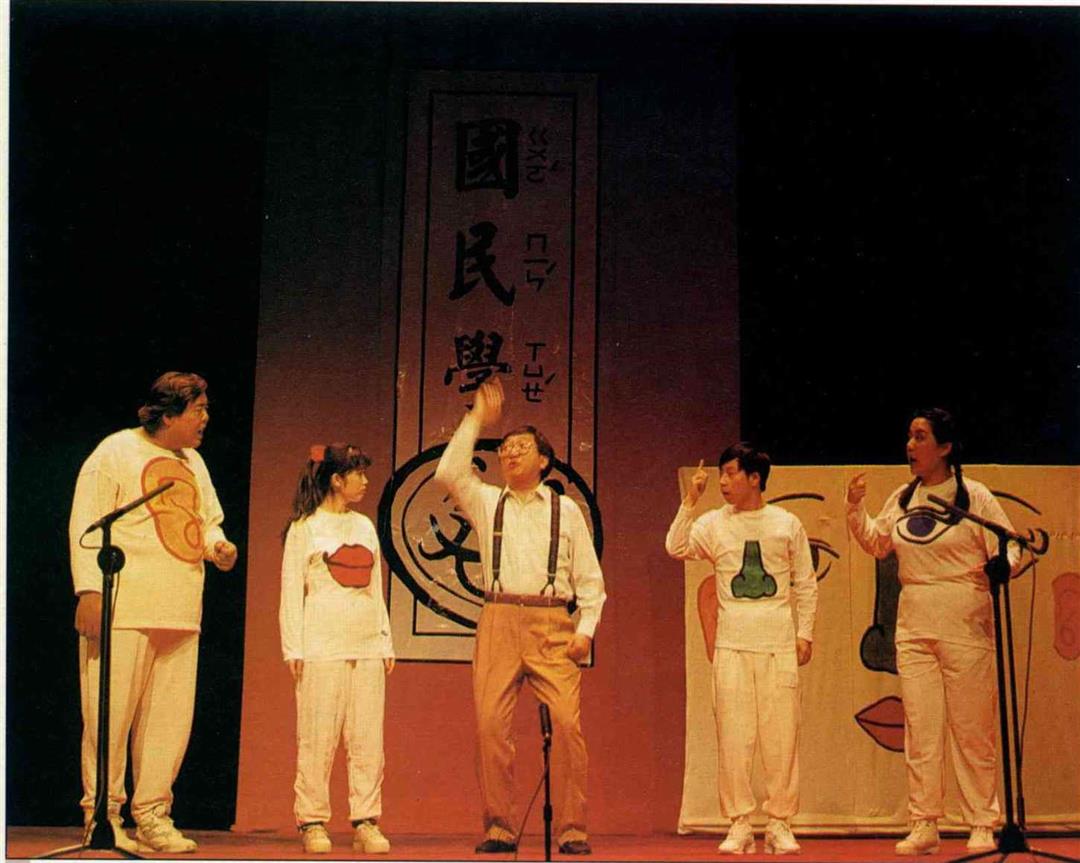

Is it a little strange to see three people or more doing a comic dialogue? This is called a "group comic dialogue." The picture shows the Taipei Musical Theater Troupe performing "The Five Senses Vie for Favors.".

Kids often recite comic dialogues to learn proper Mandarin pronunciation. In the last year or two, using comic dialogues to learn Taiwanese has become even more popular. (courtesy of Paoshih Children's Spoken Art Troupe)

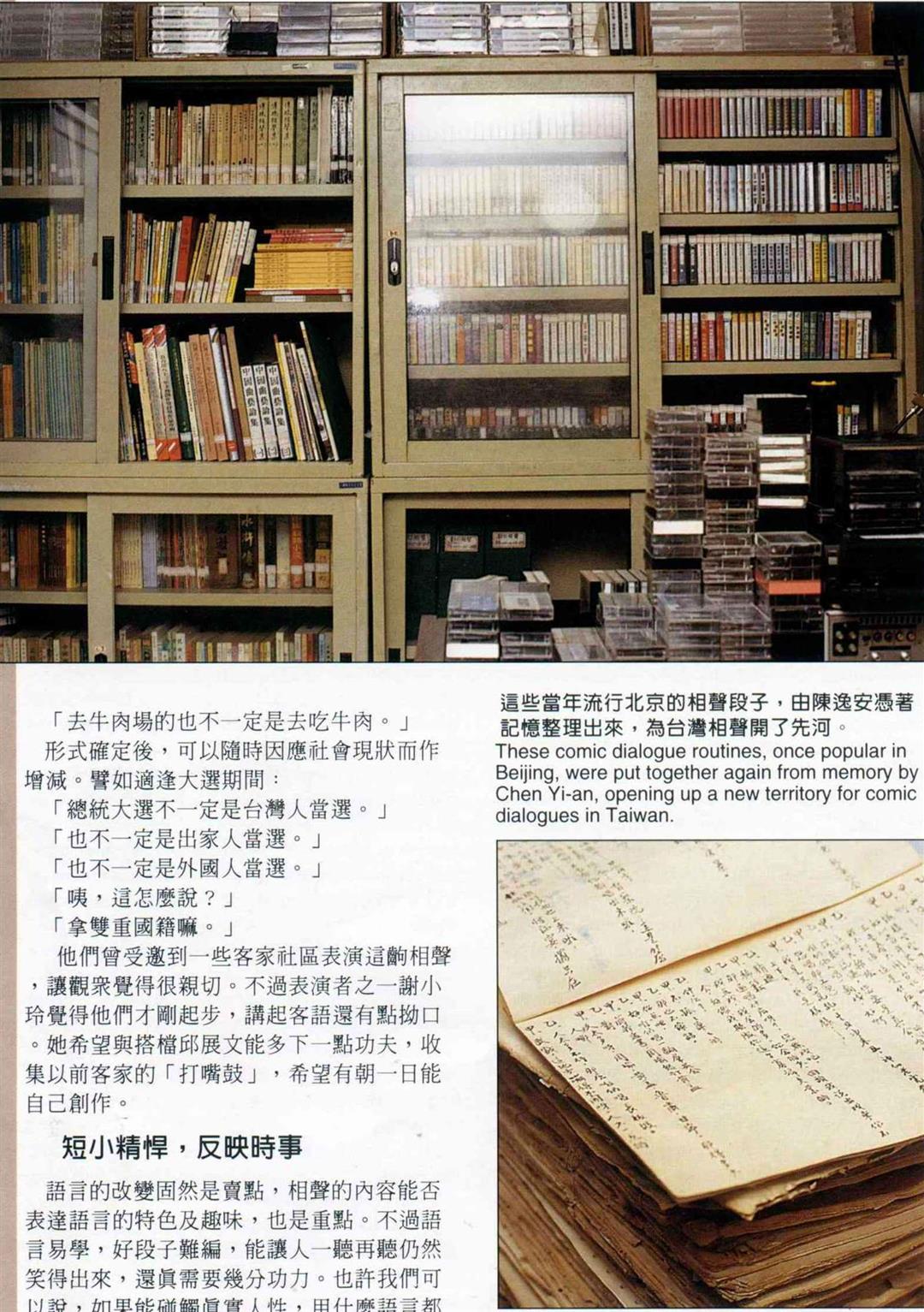

The roots of comic dialogue are in mainland China, and because of official support, its history and theory have been fully researched. These are also the principal subjects of the Hanlin Troupe's reference room.

Ah Pao and Ah Kiao's "Taiwanese Xiang Sheng" attempts to blend the techniques of xiang sheng and tapcuiko. (courtesy of Tsai Ming-yi)