These reform measures have all been necessitated by the pressure in society to pass academic entrance examinations. In particular, arduous supplementary study courses brought about by a fixation with testing into ever better schools are the great villain targeted by education reform. It is this phenomenon that has even made many parents send their children abroad. The question is, if examination questions become easier and easier, and an increasing variety of options becomes available for getting accepted at schools, will buxibans-supplementary study schools, or "cram schools" as they are often known-really vanish into history as educational reformers hope?

The Chinese are highly concerned about dietary tonics and fortifying medicines. Whenever they have the chance, they will "take in dietary supplements." This practice is based largely on the two concepts, "Fortify your weaknesses" and "Prevent sickness in advance." In this slogan-oriented era, the advertisement catch-phrase goes: "If you're sick, nurse yourself; if you're well, strengthen your body." Everyone could stand to fortify themselves, and anytime is a good time to do it. Are the ever-popular supplementary schools a reflection of this kind of "tonic culture"?

Time to bone up

When newspaper headlines revealed that passing physical fitness tests would add points to students' entrance exam scores, the reaction of many parents was, if even physical fitness is part of the exam, "should everyone send their children to a buxiban to bone up on phys. ed.?" For parents of today who are forty or fifty years old and have children in middle or high school, the shadow of "brutal cramming" is still fresh in their memories.

In September of 1968, the ROC began implementing nine-year universal compulsory education. For this reason millions of Taiwan's students were able to progress from grade school to junior high without being tested. A look back at the newspapers of the time reveals that one of the major reasons for implementing nine-year compulsory education was to "eliminate 'brutal cramming' and return to normal education." That was an era entirely optimistic about education. After nine-year education was put into effect, everyone looked forward with complete confidence. As soon as the channels for moving forward in education were opened up, people believed the kind of scene that today we sometimes see in films-a scrawny little student with a book bag on his back, studying in misery by lamplight after the sun has set, staying in school after hours to "cram hard"-would be banished from that day forward.

But buxiban culture has obviously not gone away. On the contrary, supplementary education courses have become increasingly "diversified." Taking a joint entrance exam is no longer necessary to get into junior high, but there are parents who, wishing to take precautions, worry that standards have fallen in the public middle schools that admit kids without testing. They believe it's still best to bring in an extra teacher to "shore their kids up." Only if they get into a private junior high will they "have a hope of testing into high school." For those lucky lads and lasses who don't have to take such "basic material" as Mandarin, math, and composition, the buxiban market generously offers all kinds of extracurricular curricula in "the arts"-English, rapid math calculation, computers, speed reading, art, music, calligraphy, playing go, swimming, vision enhancement training, and so forth. For nearly any sort of accomplishment that anyone can think of, there's a buxiban that offers it.

According to the Supplementary Education Association, in the last decade, since children's arts classes have taken the place of entrance-exam-oriented humanities and science classes, they have become the hot selling point of buxibans. The variety of arts classes is constantly growing, and the students are younger and younger. For example, at less than a year old, pupils can begin attending Jiber buxiban, whose main aim is building emotional balance and stamina. This is really "making sure your children don't lose at the starting line."

Laying a dragnet

In the context of such an impressive and long-lasting buxiban culture, the Committee of Taipei Historical Records held a seminar in September of last year on "Examination-Oriented Supplementary Schools in Retrospect." They invited a wide number of Taipei City's senior pedagogues, such as the prestigious 1970s buxiban teachers Hsu Chen-liang and Chang Chin-wen, affirming the decades of educational work they contributed and expressing the hope that one day, when exemplary teachers are listed on Teachers' Day, buxiban teachers will have a place too. It's a pity that not everyone is able to view buxiban culture in this way, especially those parents with children about to come of age, who must together face the pressure of the joint entrance exams.

Four years ago, Yin Ping, the author of the book Running Away to New Zealand, published in a newspaper supplement her grievances against the present-day "harsh buxiban culture." At the time, her child was attending a middle school in the Taipei area. Starting from the winter vacation of the second year of junior high, some parents joined together, rented an apartment, bought desks and chairs, and invited the best teachers from every department of the school for all-around extra "academic nutrition," cramming until nine o'clock every night. At first Yin Ping refused to make her child take part. But by third grade, under pressure from the school's teachers to keep up with the rest of the class and to "push the level of accomplishment" (all the other students were already enrolled in the buxiban, and they had moved the homework ahead of schedule), this mother who had always opposed late night cram sessions had no choice but to put her child on the buxiban roster.

Finally, for her children's education, Yin Ping emigrated to New Zealand. Her book Running Away to New Zealand, written principally to examine the problem of education in Taiwan, remains to this day on the bestseller list. It is quite evident just how many people in society share the same woes! Nevertheless, attendance at buxibans continues to irresistably rise.

Just as the range of subject matter at buxibans has expanded greatly, the style is constantly changing as well. The old model, wherein parents took the initiative to invite outstanding teachers of every subject to meet in a secret place and, throwing together a few tables and chairs, "help guide our children," still exists today, but it is only the most bare-bones approach. Today far more buxibans hire well-known teachers full-time, and set up shop near schools, using an image of professionalism to recruit students. And the small classes of the past that had a few dozen students have given way to large classes of two or three hundred.

Buxibans are increasingly professional. They offer everything from single-subject lessons that treat specific weaknesses, to generalized courses that bone up on everything. Whether you're preparing for junior high, high school, vocational school or technical college-no matter the age level or subject, the marvelously resourceful buxibans seem to be fully prepared with their own secret recipe for success.

If only you're willing to walk in the door, they'll take you wherever you want to go-"graduate school, public or private university, evening college, junior college...." Even after you have graduated from university or graduate school, there are still all kinds of career-training buxibans that will help you cross over to a new profession, prepping you for the national civil service exam, TOEFL, overseas university entrance exams, qualifying licensing examinations, and even specialized tests for journalism or the foreign service. Welcome, one and all.

The boulevard of youth?

Besides the professional buxibans spread throughout every neighborhood, Taiwan has even developed a "Buxiban Boulevard" famous far and wide. Nanyang Street, near the Taipei Train Station, is the prime landmark of Taiwan's "cram culture." This street is renowned not only in Taiwan, but also internationally. Not long ago, BBC television reported on math education in Taiwan, and Nanyang street was featured on the program.

Chou Ming, director of Julin Preparatory School, located on Nanyang Street and boasting fourteen years of history, points out that in the 1970s, nowhere else in Taiwan did buxibans specialize in testing into university. Many students from central and southern Taiwan either could not test into university or could not manage to get into the department they longed for and therefore left their homes and made the long trek to Taipei to polish their academic prowess. At that time many buxibans dedicated to testing into university started congregating in this area, because at the time the rent was cheap, and it was near the train station. Up to the present day, the image of young people disembarking from the Taipei train station after August and September of every year, carrying big suitcases, faces fraught with concern, searching for Nanyang Street, has entered the collective memory of many people.

"If a shop sign falls down on Nanyang Street and hits ten people, nine of them will be cramming for entrance exams." This may very well not be a joke. Today, because rents have increased in the area and because of its proximity to the train station, many fast-food restaurants, clothes shops and supermarkets have been added to Nanyang Street, but what still dominates the scene are buxibans and the quick and convenient businesses generated by their presence, such as cafeterias, fruit stands, diners and private study halls. The safety and hygiene of Nanyang Street's buxibans and related service shops, and the psychological adjustment of the students, are often the focus of news reports.

"One wave of the Yangtze pushes the waves that came before." One generation of newcomers replaces the old. As buxibans march into the prosperous 1990s, the reality of "brutal cramming" may still exist, yet on the face of things, what the buxiban industry is saying is, "Turn cramming into a kind of entertainment!" Buxibans have certainly changed!

The post-Nanyang-Street era cometh

Postmodern people, young, old and in-between: If your stereotype of the buxiban is a little room with tight little seats, a cramped, filthy toilet, and a teacher with a voice raspy from exhaustion, well then, you're unquestionably behind the times!

The accredited buxibans of today are most particular about "an impressive big building, brand new equipment, ergonomically designed desks and chairs, restroom facilities better than a five-star hotel's, a ceiling made from fireproof material, and lighting that 'surpasses US federal standards.'" Besides all this hardware, the pedagogical methods carefully maintain an overall appearance: The lecture is written by a panel of experts. There are special instructors to correct test papers and essays. Students sign in with magnetized cards, and automated telephone inquiry systems are available so that parents can immediately know whether their children are absent from class. Test reports are graded by computer, so students can know their progress as soon as they have finished their test.

Keeping pace with improvements in equipment, buxibans also pay great attention to packaging, taking enormous pains to produce a warm, intimate image.

During the summer holidays, one jiajiaoban (a buxiban founded by a single teacher) located on Hangchou South Road and famous for its star teachers, especially rented a tour bus to pick up students at pre-arranged locations, so that they could conveniently attend the school's demo presentations and classes. Throughout several torrid days, in front of the doorway to the brand-new building housing the jiajiaoban, pedestrians passing by could often see a spectacle such as this: streamers lined up in a row, emblazoned with the name of the school, "Buxiban X English," "Buxiban X Math," and young people lined up in two queues on either side, wearing T-shirts advertising the school. Why did those streamers flap in the air, arrayed as if to welcome honored guests? No need to ask-it was to lure new students.

In the 1970s and 1980s, when the buxiban industry had not developed to its current level, it was mostly public school teachers who taught buxiban classes. These after-school classes could first of all increase teachers' incomes. Furthermore, they were more flexible in terms of the progress levels expected and the teaching materials which could be used. As one buxiban educator observes, "To put it not so nicely, you had more latitude to voice opinions about current events, or slightly 'off-color' humor, that you couldn't express in public schools."

Most importantly, nearly every "big-name teacher" in the buxiban business had a set of gimmicks to sort out major points and condense the teaching material. They were able to arrange textbooks' important details into compartmentalized lectures. Using all kinds of special techniques like "association" and outlines, they could actually ram the crucial points of exams into the students' brains, and as an extra, they could spin off terse and witty jokes. These were the makings of a "star teacher." For this reason, in the context of that era, which highly prized a teachers' renown, "brand name" was of course the first consideration. For example, having teachers who had taught at Taipei First Girl's School or Chienkuo High School, or were graduates of a prestigious school like National Taiwan University (NTU) or National Taiwan Normal University became the focal point of buxibans' advertisement campaigns.

Today, every joint entrance examination is graded by computer, and prestigious teachers' methods of summarizing and arranging material "are definitely effective on the test." Chou Wei-han, who tested into NTU's medical program this year, says, "They more or less teach us how to order the knowledge in the textbooks." Nonetheless, after the test is over, "whether this 'dead knowledge' is of any use, I don't know!" he admits.

A star is bred

Eventually, education agencies dedicated themselves to "nabbing the buxibans," setting down strict regulations that teachers employed in public schools could not teach supplementary classes on the side. Therefore, buxibans could no longer dare to openly use public school teachers as calling cards. This is why the focus for attracting students shifted toward flaunting the rate of successful entrance exam passage, through such methods as concentrating on equipment and facilities, or aftersales service (for example, instructors may be available after class to help answer test questions or edit essays). Senior buxiban teacher Hung Chung relates that in 1987, one Taipei buxiban utilized a tactic common among real estate companies-they trained a large number of recruitment personnel and part-time student workers and sent them to places frequented by young people, such as department stores, using "human wave" tactics to draw in students. This was the very inception of the buxiban marketing strategy that has prevailed ever since. Currently, most buxibans' market methods deviate little from this paradigm.

"Recruitment personnel are more important than teachers," was once the lament of buxiban educators, but in the midst of such fierce competition, the most reliable credentials are word-of-mouth endorsements, like "They teach better," or "They make test scores go up." The buxibans of the 1990s therefore seem to have returned to their original path, but what is different from the past is that two out of three successful teachers "have never taught class formally," says Chiang Chun, a young buxiban teacher. The vast majority of these "star teachers" are usually lured into teaching buxiban classes while in college or upon graduating. Because "they enunciate crisply and teach in an interesting manner, and the students like them," Chiang says, they linger in the buxiban world and become career buxiban teachers. His wife, Ruby Hsu, is one example.

Also different from the past, many of these successful teachers of the buxiban world have been cultivated by the buxibans. "They are nurtured along like movie stars," says senior teacher Tseng Cheng-ping. For this reason, they should be young, vivacious and also attractive-most men are handsome and debonair, most ladies pretty and extrovert. To put it another way, besides being able to teach well, other exterior requirements for "packaging" are also important.

Thus, even star teachers' names are being designed. Besides being graceful and refined, they must have a clear, lovely ring to them. The trend is to be evermore similar to some character from one of Chiung Yao's romantic novels-Chen Li, Kuo Yang, Hsu Wei, Chu Chih-mo, Tu Yun-tien... Some buxibans even put teachers' faces on posters, photographs and drawings, hanging them high in front of the buxiban door. In advertising campaigns, they are made into fabulous superstars, even appearing on the sides of buses or on cable TV. A teacher may have an image built up as a good joke teller, an exercise buff, or a kind parent with a baby in her arms, all to make a sale.

Preparatory school, or fan club?

People in the buxiban business all say that they are making an accommodation to the trends of the time, adopting emotional appeals and catering to the needs of parents and children. LCC Preparatory School director David Lin points out that middle school and high school students all more or less have the tendency toward hero worship; so, packaging teachers as celebrities is simply giving the students what they want. But for many adolescents, peer pressure plays a crucial role; many middle and high school students are unconcerned about other considerations. "My classmates come here for study, so I come here too," says Huang Chun-chieh, who was accepted as a high school freshman this year. But "chit-chatting about whether the buxiban teachers are good looking, what kind of clothes they wore today, or what kind of pretentious jokes they told, how weird the laughter was..." helps relieve anxiety and makes them feel comfortable while toiling under an intense load of studies. Even in regular school, the classmates that go to a certain buxiban will congregate in a clique. For instance, when solving math problems, the "Buxiban A" group and "Buxiban B" group will naturally fall into teams. To David Lin, this is proof that in buxibans, children are studying not only their homework, but also "social interaction."

This may also explain the abnormal phenomenon in today's buxibans, especially in jiajiaobans that make celebrities of the teachers, of classes ranging between 100 and 300, or even as high as 600 students. The buxibans' explanation is that "the more people there are, the more robust the business." David Lin relates that they had tried classes of 40 or 50 students. But as it turned out, business was not good, because "as far as the kids are concerned, whether or not they really want to be there, attending a buxiban is only a kind of 'rite' they are obliged to perform, either for their parents or for themselves." Lin observes that what children like is "the feeling of nestling among others, surrounded front, back, left and right." English teacher Ruby Hsu believes that in terms of English lessons, big numbers are better than small numbers, because "you have to memorize English by rote, and a lot of people can recite together in a loud voice, making the atmosphere of class more energetic."

How does one hold a class of five or six hundred? This is certainly a good question. The classrooms have become bigger and bigger, some buxibans even claiming to have "the biggest classroom in the world." They have also ingeniously divided the classroom into several sections. The earliest to sign up get to sit in the best section-this in turn becomes another sales point. It projects the same feeling as a Michael Jackson concert-those who are too far away to make out the teacher's face study via the "assistance" of simultaneous television broadcast. This is called the "audio-visual section." In like manner, students have jokingly named the area opposite the audio-visual section, where one can actually see the teacher clearly, the "rock-and-roll section." And at registration time the human wave can begin queuing up at 5:30 in the morning, just for the rare chance at a seat in a special area.

Where are today's children to go?

How can a buxiban recruit so many students? Teacher Tseng Cheng-ping avers that the crux of the matter lies in the method of recruitment. Today most buxiban sales personnel are or have been students of the buxiban. Using their own network of personal connections-relatives, friends, neighbors and classmates-just like a pyramid scheme, one person can bring ten others to the class. Whether the kids are calling others on the phone to invite them to demo classes, hanging out "helping make the place look busy" or looking after younger students, from their point of view, a "part-time job" at a buxiban is relaxed, there's no time restrictions and you can, as they would put it, "goof off." With the money they earn, they can watch movies or shop. Why not go for it?

A more important question is, during their free time out of school, if these kids don't attend a buxiban, where can they go? High school freshman Huang Chun-chieh says that he signed up and listened in on buxiban class because he was worried that once he started high school he would have a hard time keeping up with most subjects. "If I get a little extra practice, I'll feel more assured," he says. Furthermore, at home, "when there's nothing to do, there's nothing to do. If I go to a buxiban, I can bump into my old classmates and meet new ones. There's more stuff to do there."

Buxiban teacher Michael Kao believes that nowadays, as both mother and father are busy, a buxiban is unquestionably a place for kids to go outside the home which parents can trust. Kao jokingly remarks, "At least they won't be watching TV, playing video games and opening the fridge like they would at home. Then they would have fights with their parents, and it would be bad for family relations." Not to mention, in terms of school work, buxibans can certainly help children build confidence. "Everyone says we're just 'force-feeding the duck' [cramming the students with test answers], but I would rather say, 'Practice makes perfect.' This is especially true when it comes to test results." Moreover, if children run into difficulties in their studies and torment their parents with them, it might not be unwise to let a buxiban act as their "agent." When looked at in this perspective, aren't buxibans actually performing a social service, indirectly solving many people's family problems?

Where now, buxiban?

Isn't it just so? Urban life is full of both blessings and pitfalls. Parents have become busy. What if the dream of "giving students back to their families, giving youth back to students" were to come true? Once you have students and their youth back in your hands, what are you going to do with them?

And take a closer look: "Buxiban X's Heart-Parent's Heart"; "We understand the feelings of parents, and protect the feelings of children"; "Don't worry, don't fret-Buxiban Y will help you get your confidence back"; "Help your child find a pair of straight, reliable shoulders"; "Buxiban Z keeps the last light burning for you".... National Chengchih University professor of advertising Cheng Tzu-lung comments that buxiban advertisements have already moved far beyond the simple sales tactics of the street-side hawker. Just like car ads, they have come to stress "company image." But in terms of contents, buxiban ads can hardly avoid reflecting the realities of contemporary society: A parent's heart, confidence, shoulders, a light... In today's Taiwanese society, how many familial functions can parents morally justify paying money to hand over to buxibans?

Looked at from a different perspective, aren't the ideals which buxibans put forward-worshipping prestigious schools, stressing school ranking and star teachers, hunting out new buildings and high-tech, computerized equipment-really the societal values which all of us struggle for? For many years now, the well-known teacher Ruby Hsu has driven a Toyota sedan. Her students sometimes laugh at her, saying, "Teacher! How can you drive just that?" The children mean no harm by the statement, but it reveals a great deal about society's values. From young people's point of view, successful buxiban teachers have high incomes; fine clothes, good food and a luxury car are all musts! In other words, this is the image of success. And don't they study and study so that they can pass that test, whether for high school or university, to "make a name for themselves in one fell swoop," and then have a bright future and an easy ride?

It's all for the sake of-education?

Many people wonder if in fact there aren't many other incentives for the massive presence of buxibans in Taiwan besides the joint entrance exams. According to statistics of the Ministry of Education, in the present day 1,130,000 people, or one in every twenty of the population, attend buxibans every year. The fact is, you need not refer to Ministry of Education statistics; just take a look at little Ah Hua or Ah Hsiung next door. How much time do they spend every week in buxibans? Kids who "polish their studies" four days a week, not counting Sundays, already look harried and weary.

Of course, you can also flaunt convention and emigrate just like Yin Ping. But will you really be able to completely escape buxiban culture? One prestigious buxiban math teacher posted an advertisement in the Mandarin Daily News. One student he had taught before saw the ad overseas and gave him an international phone call. "Teacher," he said, "do you want to immigrate here and teach? We've already found a bunch of students here. We could start classes immediately...."

As Asian values have recently come into vogue in Europe and America, education is one of the aspects most highly lauded. British experts have discovered that Taiwanese children's mathematical abilities are two years ahead of British children of the same age. Many have therefore called for abandoning small-group education in favor of large classes, Taiwan style. At dinner time, a camera of the BBC focuses in on a group of buxiban students on Nanyang Street. (They appear to be lined up to buy noodle soup with oysters.) An off-screen voice emotionally comments: This is Friday night. What are the students queuing for? ...education!

As one might expect, Confucian culture has many different aspects, and buxiban culture is likewise very broad and deep. Could it be that those close at hand are repelled, and those far away are attracted?

p.25

In the 1990s, more and more students attend exam-oriented buxibans. Class rooms are constantly growing larger in size, equipment constantly improving. Have we entered the age of "recreational cramming"? Why exactly do they attend?

p.26

It appears that the changes in buxiban culture have been enormous, but in some places it has changed little over the decades. Nanyang Street, crowded with buxibans, has already become a landmark of Taipei.

p.27

Not long after exam results were posted, this student moved into a buxiban dormitory, devoting himself to the fierce competition of next year's joint entrance exam. In our society, are entrance tests really a gauntlet of life or death?

p.28

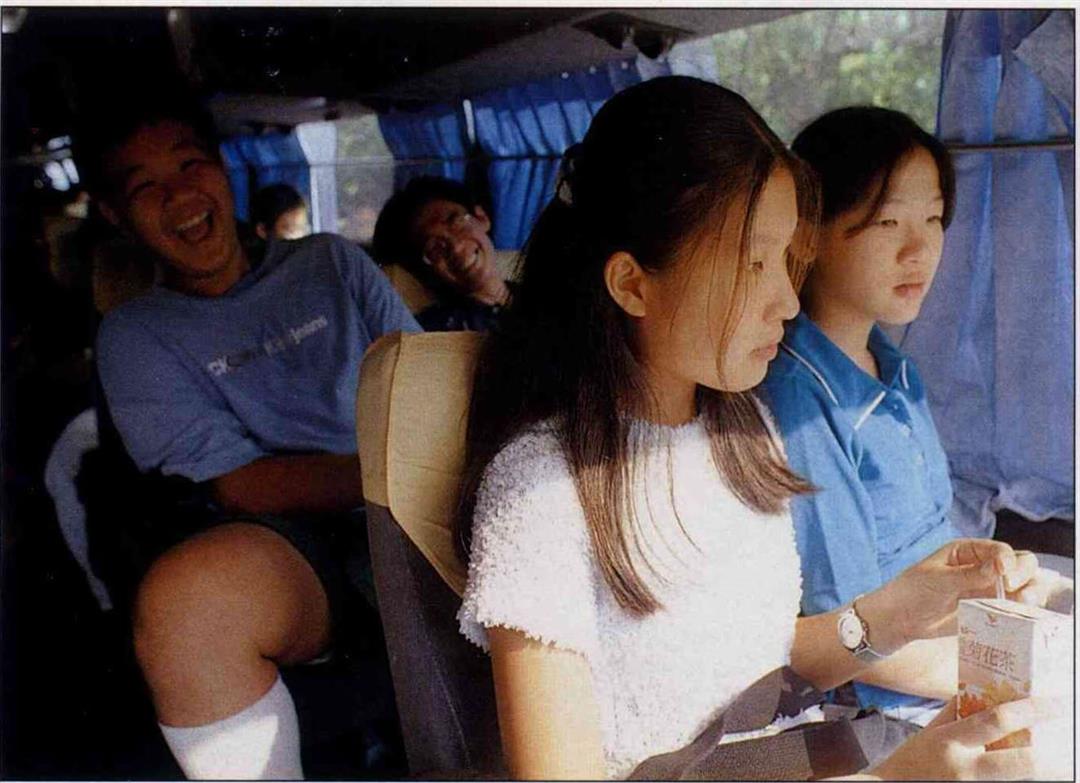

Come one, come all! Have a ride on our tour bus. Where we're going is not a famous scenic spot-it's a buxiban. This is one of the many creative ways supplementary schools attract new students.

p.29

Is cramming a form of entertainment? In the past buxiban students came laden with a big book bag. Today, they carry a travel bag and a basketball. Even if you're late or skip class altogether, it doesn't matter-the video cassette recording will help you.

p.30

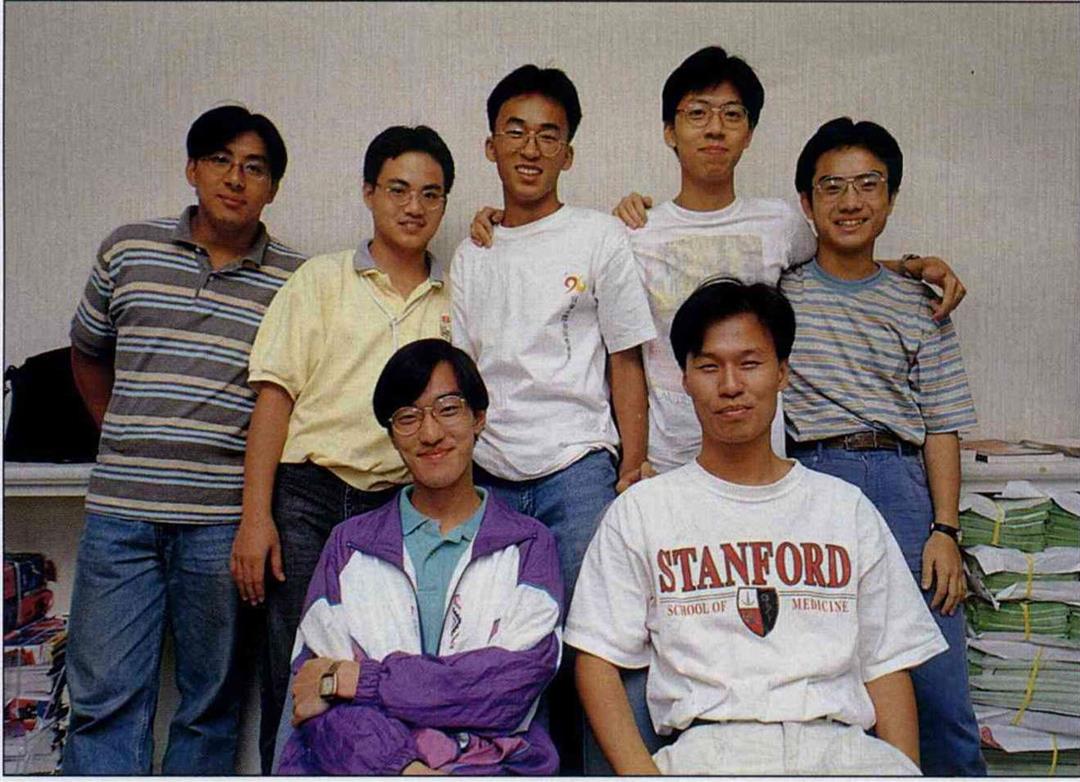

Seven living buxiban advertisements-NTU med school candidates. The benefits which the buxiban gives them are free tuition for a whole year while they study to retake the exam, free housing and a guidance counselor to help them solve problems both academic and personal. Buxibans unabashedly display today's social values and worldly ambitions.

p.31

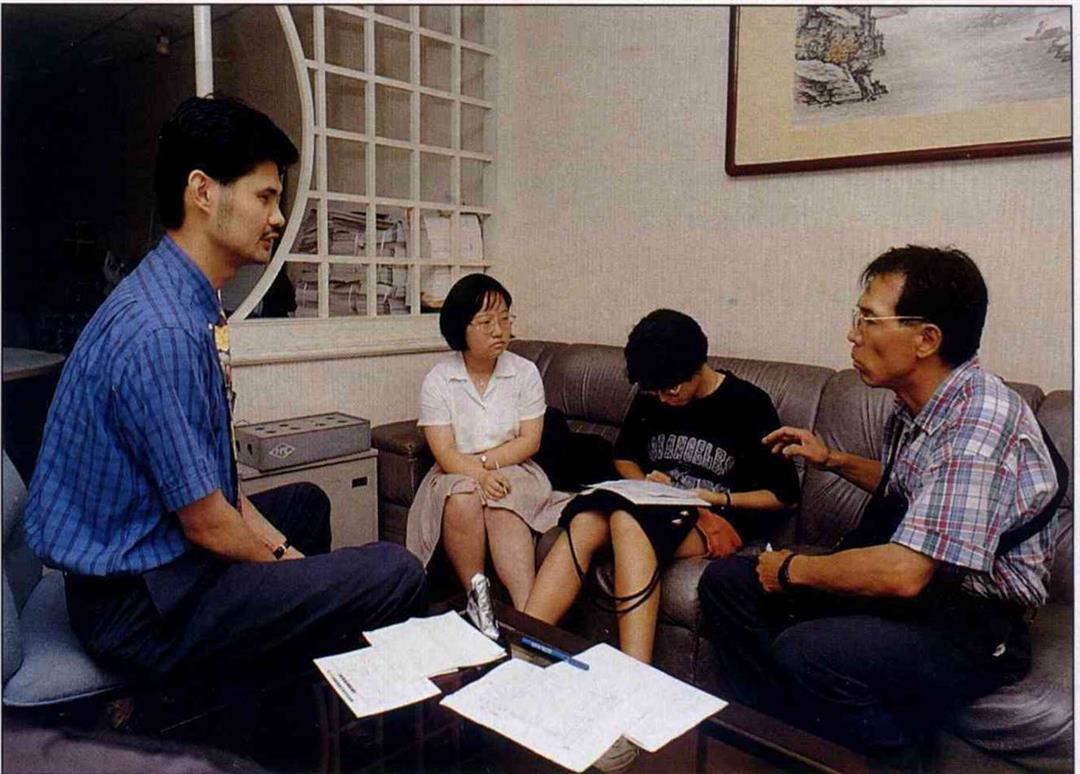

"Even though my child has gotten into NTU, I think she should be able to get into the medical program. I entrust her to you; take good care of her." ...One scene at a buxiban after the joint entrance exam.

p.33

For thousands of years, Chinese students have striven to "finish first in the imperial exams and receive employ as a high official." What the buxiban provides are merely the tools to achieve that end. (rephotographed from Chinese Popular Prints)

Come one, come all! Have a ride on our tour bus. Where we're going is not a famous scenic spot--it's a buxiban. This is one of the many creative ways supplementary schools attract new students.

Is cramming a form of entertainment? In the past buxiban students came laden with a big book bag. Today, they carry a travel bag and a basketball. Even if you're late or skip class altogether, it doesn't matter--the video cassette recording will help you.

Seven living buxiban advertisements--NTU med school candidates. The benefits which the buxiban gives them are free tuition for a whole year while they study to retake the exam, free housing and a guidance counselor to help them solve problems both academic and personal. Buxibans unabashedly display today's social values and worldly ambitions.

"Even though my child has gotten into NTU, I think she should be able to get into the medical program. I entrust her to you; take good care of her." ...One scene at a buxiban after the joint entrance exam.

For thousands of years, Chinese students have striven to "finish first in the imperial exams and receive employ as a high official." What the buxiban provides are merely the tools to achieve that end. (rephotographed from Chinese Popular Prints)