A Taiwanese Banana Yoshimoto

Certainly, with her gentle, ditzy, funny, and kawaii prose, Cheng shows no sign of pretensions to produce refined literature. But she is prolific in a way that most stars-typically "one-book wonders"-can never hope to be.

Cheng's work draws obvious comparisons. Some in the pop music world have referred to her as "the Cheer Chen of an earlier generation" because both have sweet voices and both came to understand love through travel.

Those in the literary world are more prone to see her as a latter-day San Mao. Both opened the eyes of Taiwanese readers to travel, lived for years in Europe, and married Europeans. Both also produced addictive works heavily flavored with their own personalities. But Cheng and San Mao differ in significant ways. Where San Mao was a sensitive, melancholic figure, Cheng has a sunny personality that constantly shines through in her comic take on life and her refusal to fret unnecessarily.

Cheng's approach to writing makes her something of a Taiwanese Banana Yoshimoto. In spite of winning awards and accolades for their early work, both have sought to simplify and streamline their prose. Because they believe that their words have the capacity to heal readers, both feel that it is more important to make their work accessible than to see how "literary" they can be.

The fact that such comparisons can be made is suggestive of Cheng's multifaceted character and of the richness of her work. Interestingly, Cheng had no background in literature; it's her musical training that most strongly influences her writing.

A cello player since childhood, Cheng studied the instrument with Ma Xiaojun (Yo-Yo Ma's father) at Hwa Kang and has been heavily influenced by German classical music, especially that of Schubert. Cheng says that she "writes songs that resemble classical pieces, with a heavy emphasis on meter; and writes books like operas, with a focus on scenes."

Every time she finishes writing a song, she immediately records it and gives it a listen. If she finds the lyrics awkward or difficult to understand, she revises them. Pop songs rely on simple language to remain accessible, but still need to be catchy.

"Men's Talk," which she wrote for Stella Chang, is a case in point. In it, a woman wonders why her lover doesn't confide in her. "You and I are like the earth and sky; you're the clouds flying on the wind, while my tears flow like a river." There's a poignancy to this woman's unbridled desire for a man with whom she wants to share everything.

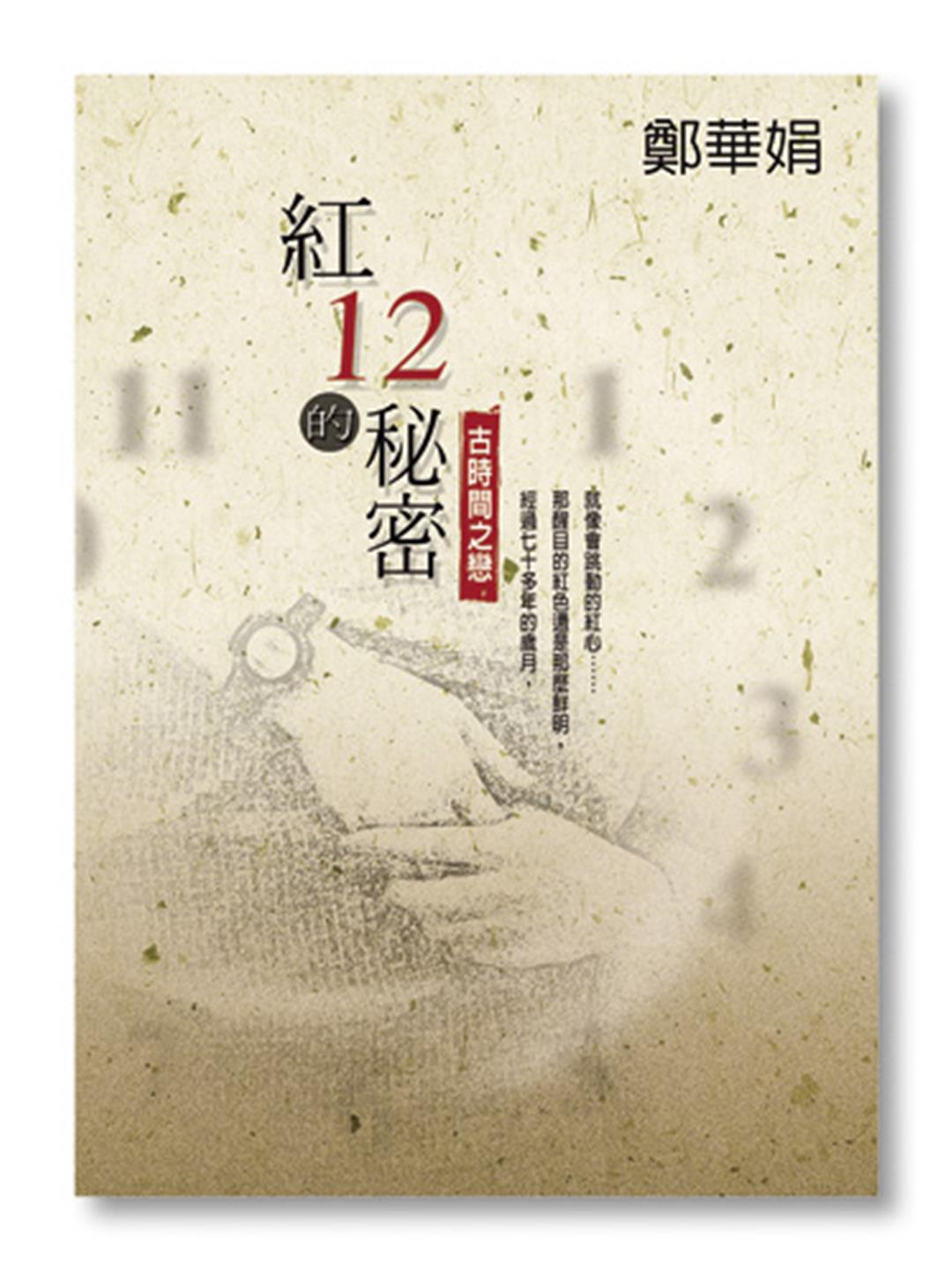

The Secret of Red 12 is Cheng's only novel to date.