Do people have the right to choose to die? Is the legalization of euthanasia moral? Does euthanasia go against the Chinese conception of death? In Taiwan, the problems surrounding this issue are further complicated by an incomplete social welfare system.

Lee Sheng-long, who is head of the Health Law Committee attached to the Taipei Bar Association, recalls that ten years ago he participated in a discussion about euthanasia, at which time the voices opposed were overwhelming. Now, a decade on, public sentiment has shifted dramatically. Many polls put the share of people supporting mercy killing at 70-80%.

Divergent opinions

The Greek roots for euthanasia, "eu" and "thanatos," mean "good" and "death" respectively. Early this century a Japanese doctor made a translation with the Chinese characters 鈍綢跛, which mean "peaceful, happy death." The translation has since come into general currency in the Far East. Yet there is no single definition for the term, and the public has many different understandings of it.

Chin Hsian-wei, an ethicist, proposes the following definition: Choosing an action or non-action to eliminate suffering with the intention of leading to death, or choosing an action or non-action that directly leads to death.

The distinction between "voluntary" and "involuntary" euthanasia lies in whether a patient has the ability to express a willingness to die. What Wang Chao Hsi-nien requested for her daughter was involuntary euthanasia. Even in Holland, where euthanasia has been practiced for many years, and the Northern Territory of Australia, where it has been recently legalized, involuntary euthanasia is not allowed. To put it another way, choosing by one's own free will is a basic precondition for euthanasia.

Based on the distinction between "action" and "non-action," there are two types of euthanasia: "passive" and "active." "Active" euthanasia uses medicine or medical practices to kill a patient, whereas in "passive" euthanasia the withholding of medical treatment leads to a patient's death.

But modern medicine is so complicated that it's hard to draw clear lines between active and passive, action and non-action. And for terminal cases, survival is impossible no matter how active or passive their treatment.

Take, for instance, the case of Chang Hsiao-tsu, former president of Soochow University. In the view of modern medicine, the hemorrhaging in his brain made him impossible to save. The drugs he was taking and the machines he was hooked up to were just extending his period on the brink of death, but not really extending life. And so turning off his respirator did not constitute euthanasia.

Legislator Shen Fu-hsiung, who worked as an internist specializing in kidney disorders for 20 years, says that it isn't appropriate to divide euthanasia into the "active" and the "passive." Based on how much the length of a patient's life will be altered, he divides cases into three sets of circumstances: (1) When a doctor's lack of action shortens a patient's life, such as when a patient will die through the natural course of his disease when active measures (meaning those beyond simply feeding him and allowing him to urinate) are not taken. (2) When active measures that have already been taken to extend a patient's life are then withheld, such as by disconnecting a respirator. (3) When active measures are taken to shorten a patient's life, such as by giving a lethal injection.

Shen Fu-hsiung holds that the first two cases could be categorized as "natural death" or as "a refusal to prolong life at the brink of death," which would be made legal under the proposal put forward by the Department of Health. He holds that only the third type, which actually shortens the patient's life, can be called euthanasia.

The patient or the caregiver?

For many years euthanasia has been something people have been careful to raise their guard against. Apart from its being a matter of life and death, the outright rejection of it was also a legacy of Hitler's gruesome deeds. In 1939, Hitler advocated "exterminating valueless life," implementing a "euthanasia plan." Over the next five years, great numbers of children with birth defects and mental patients were executed. Euthanasia acquired such bad connotations that people would turn pale at its very mention.

Religious groups are euthanasia's strongest opponents. From a biblical standpoint, life is something given by God, and not something that can be chosen by man. Man is not life's master, but rather only its caretaker and so has no authority to decide at what time and by what method to end life. Hsieh Hung-chung, director of studies at the Ling Leung Seminary, points out that suffering can give people a chance to approach God and come to a better understanding of the meaning of life. One ought to bear with great suffering, rather than actively seek death.

As opposed to Christian leaders' clear stand on the matter, Buddhists, who are opposed to killing, have not spoken out loudly against euthanasia.

A few years ago there was an incident which shook society. A Buddhist medical worker who could not bear to witness the suffering of the severely ill in their last stages and the hardships imposed on families for the long-term care of "human vegetables," "played God" and let some of them die. He was discovered and prosecuted. At the time, many people in society sympathized with him, and the families of those who died were particularly vocal in offering their support.

Nun Chao Hui, a director of the Life Conservationist Association, points out that although Buddhism has no theory of creation, based on the teaching that every life is of value and the strong love that one should have for one's own body, not only should one not kill others, one shouldn't kill oneself. Yet while this makes it wrong for people to choose euthanasia for themselves or for family members, because the choice is made based on merciful feelings, euthanasia poses a dilemma, which is why Buddhism has chosen to be silent on this issue.

Savior? Executioner?

In ancient times, before the advances of modern medicine, birth, aging, disease and death were natural processes that were entirely consigned to God, which left no room for debate. Modern medical technology and progress, while allowing people to live longer, have also made it possible for terminal patients to stay in a state where they won't immediately die, but where living may mean enduring mental and physical agony. How does this jibe with moral conceptions? Where does life end and death begin? These questions are becoming harder and harder to answer.

In America, euthanasia is illegal, but Jack Kevorkian, Michigan's "Doctor Death," has successfully assisted more than 20 patients commit suicide, challenging the law time and time again. Although disagreeing with his methods, many doctors support his ideals and respect his courage.

Medical institutions are scared of charges that they engage in euthanasia and reject playing the role of "executioner." The reason given is always one of the following: "It runs counter to medical principles!" "Doctors have a duty to save people, not kill them!" "Who is willing to be executioner?" Or, "Shortening life is the same thing as causing death!" Kao Ming-chien, a professor of neurosurgery at National Taiwan University Hospital, says that doctors can only perform "passive euthanasia" by not actively treating patients: "In this way medical resources are not wasted, and moral principles and medical ethics are not so clearly flouted." He notes that many patients, mercifully, are allowed to die slowly in this way, after stating that they've "had enough."

Doctors point out that they must abide by their profession's code of ethics. But no doctors can explain why not taking action and letting a patient die is benevolent, whereas "compassionately assisting someone to die" is deemed as murderous behavior that makes the medical community shrink back with revulsion. Where exactly does one draw the line between saving people and killing them?

The right to die

Whether people have the right to die is a question that can't be avoided in any discussion of euthanasia. Ken Chiu, who is the president of the Taiwan Association for Human Rights, holds that people, more than merely having a right to life, have a right to life with dignity. If they lose all dignity, from a human rights angle they ought to have the right to let go.

From a moral standpoint, there is also room to support euthanasia. Swun Hsiao-chih, an associate professor of philosophy at National Taiwan University, believes that morality is an affirmation of one's own conscience that can't be controlled from the outside. Even if it breaks with medical principles or is illegal, euthanasia is not necessarily immoral. "Abroad there have been cases of people breaking the law in order to administer euthanasia to their friends or loved ones. Such acts are suitably described as great displays of moral courage."

Some people wonder about exactly to whom mercy killing is being merciful. The truth is that the dilemmas faced by families of such patients are beyond most people's ability to understand.

The mother of Wang Hsiao-ming once said, "If euthanasia was possible, Hsiao- ming would be released, but I would never pass another happy day in my life."

One patient in the latter stages of throat cancer was all skin and bones and in such great pain that he didn't want to live. Several times, he communicated with his friends and loved ones that he hoped that his respirator could be turned off, but his wife objected. His wife's reason for not following his wish was this: "If you just did it on the sly it would be one thing, but once you have told me about it, there's no way I can just close my eyes and watch you die." Eventually, this patient, unable even to turn off his own respirator, had to just bear with the pain to the very end.

Let their families live in peace

Lin Wan-yi, a professor of sociology at National Taiwan University, holds that current discussions of euthanasia are all about questions regarding the patient's rights and neglect entirely the rights of the caregivers: "It must be considered that people are social beings and live among other people." Lin points out that many patients' conditions put great financial, physical, psychological and temporal pressures on those caring for them, severely affecting their caregivers' own rights to survival. He believes that while there needs to be prudent consideration about whether to allow euthanasia for patients, the perspective of those who will be left behind should also be considered.

Hsieh Hsien-chen, the president of Taipei Medical College, wrote a living will as early as eight years ago: "If there is no hope for me mentally or physically, I request that people just let me die with dignity." His own parents' deaths had deeply affected him. His father and mother had died two and three years before, after long hospitalizations for strokes, high blood pressure and diabetes. At the time he was the president of the Kaoshiung Medical College, and in spare moments from work would visit them in their rooms. His parents were very dissatisfied that their son, who was a doctor himself, could not lessen their pain.

"I studied medicine and know that it has its limits, but my parents couldn't understand. They thought that they had worked so hard to raise me and put me through medical school, but that it was all for naught," he recalls with a sigh. He doesn't want his children and grandchildren to have to experience the same kind of difficulties.

Although Hsieh had his living will notarized in the local Kaohsiung courts, since euthanasia is still illegal, the will won't be heeded. He hopes that if one day euthanasia becomes legal, decisions can be made on a "case-by-case" basis, so that if people have made clear declarations of intent, at least their children and grandchildren won't be accused of being unfilial.

Beyond the letter of the law

Using a man-made method to determine whether people die is fundamentally against the "the right to life" guaranteed by the ROC constitution. Article 275 of the criminal code states that encouraging someone to commit suicide, assisting in a suicide or keeping a promise to kill someone is punishable by a term of not less than one year and not more than seven.

The law can't punish those who commit suicide, but it does punish those who assist in suicides, despite their having acted on their victims' behalf-for criminal liability is not "made to order" but must be applied universally.

Holland was the earliest country to allow euthanasia. Although euthanasia is still officially illegal there, such cases are not prosecuted.

In 1994 the state of Oregon passed a "Death With Dignity Act," but last year US federal courts ruled it unconstitutional.

Strictly speaking, the Northern Territory in Australia is the only place where euthanasia is legal. Yet there doctors are still unwilling to practice it, worrying that the courts and the legislature will overturn the law, and that they will be charged with murder.

Benevolent murderer

In Taiwan euthanasia is not legal, yet "passive euthanasia" in which there is tacit understanding between families and doctors is not uncommon. A "natural death law" has not been passed, but patients on the brink of death have for years refused life-saving procedures.

The Chinese hold a conception of "leaves falling to return to their roots," believing that people should die at home or otherwise they won't be able to find their way back as spirits. And so when patients are just about to die, their families will often ask to take them home. Some patients who require respirators and oxygen will have canisters brought home with them. When the oxygen is used up, the patients will die "naturally."

Facing this big matter of life and death causes people to act in all sorts of strange ways. Chao Ko-shih, an associate professor at National Yang Ming University who has abundant clinical experience, gives this example: There was a woman in her eighties with advanced cancer, whose sons and daughters went to a fortune teller about her illness. The fortune teller said that if the old woman died on a certain month, day and hour, the family would prosper, and so at first they did all they could to preserve their mother's health. Unfortunately, shortly before the designated hour, the mother's breathing and pulse stopped, and the family implored the doctors to save her. As a result, all possible life-saving procedures were tried: electric shock, heart massage. . . . Tubes were stuck in all over her body and they tried resuscitating her three or four times and gave her countless numbers of injections, until finally the time came and the relatives said, "OK, you can take out the tubes now."

Another kind of choice

Some people worry that once euthanasia is legalized, "the right to die" could become "the duty to die." Old people, poor people, and people with chronic diseases could be pushed to choose "voluntary euthanasia," in order to prevent tiring out their family and society. In fact, this happens even now.

If euthanasia would become legal before a complete social-welfare and health-care system was in place, society's lack of benevolence could become a reason for carrying out mercy killings. Wang Hao-wei, a psychiatrist at NTU Hospital points out that today the issue of euthanasia is complicated because people want it to solve all sorts of problems, including those caused by the lack of a complete social-welfare and health-care system.

With such a system, the weak wouldn't be compelled to choose euthanasia to save resources. With full coverage provided by the state, so that terminal patients could be assured of having hospital rooms and good all-around care through the course of their illness, patients would less often find their pain unbearable and their lives lacking dignity.

As Chao Ko-shih says of 200-300 advanced cancer patients she has cared for over the last three years: "When they were in pain, 100% of them wanted to die, but when they got relief from pain and control over their illness, not one wanted to die."

Patients with clear minds are strongly influenced by emotional factors: "Changing their minds three times over the course of a week is normal," she says. Patients without clear minds couldn't really care less either way. Kao says that when many people ask for euthanasia, it's really an emotional problem. If their families were more attentive to their wishes, giving them much-needed "spiritual medicine," most of them would feel much better about things.

But it can't be denied that medicine offers no relief to some patients nearing death. And those who seek euthanasia do not do so entirely because they are terrified of the pain the disease causes. And so while supportive medical care would reduce the number of people who would choose euthanasia, some would still choose it.

An eternal problem

Generally speaking, "passive euthanasia" has long existed in Chinese society without much controversy. Still, to be prudent, a system with legal guidelines ought to be designed. For instance, a living will demonstrating the patient's own desire could be required, or "the conditions for refusing measures to extend life for those on the brink of death" proposed by the Department of Health could be adopted. These will give people authority to choose for themselves whether they want to use high-tech support systems to extend their lives as they near death.

"Active euthanasia," in which steps are taken to artificially shorten life, is far more controversial.

Shen Fu-hsiung believes that people should only be allowed to shorten their natural lives in an environment that is extremely respectful of life. "Our society hasn't got to that point yet. Although we are greedy for life and fear death, we don't really respect life."

NTU hospital's Wang Hao-wei says that Taiwan hasn't got to the point where it can start discussing active euthanasia, because to people in Taiwan life still largely involves medical, biological and physical questions, with religious questions only being reexamined over the last few years. Discussions of personal philosophical questions are still a long way off. "Only when 'what do we want from life?' becomes a hot topic, will we be able to discuss euthanasia," he says.

Swun Hsiao-chih says that the principle of choosing the lesser of two evils may provide a little room for maneuvering. Whereas something may ordinarily be impermissible, in special circumstances it may be allowed or even required. "There is much to life that is not black and white." Indeed, euthanasia is a topic that may forever inspire debate and never provide black-and-white answers.

Photo

p.40

Collage designed by Liao Tsu-wen

p.42

Few people ancient or modern have not been concerned about the great passage between life and death. When relatives fall seriously ill, loved ones can neither bear to see them suffer nor bear to see them go. When will this day-in, day-out torture end? Is euthanasia a reasonable choice for them? (photo by Diago Chiu)

p.43

In place of euthanasia, compassionate care can ease the suffering of terminal patients. And doesn't it fit better with conceptions of morality? (photo by Diago Chiu)

p.44

Whether euthanasia should be legalized is a hard question that will always stir controversy. Over the last decade, the Creation Social Welfare Foundation has put on three seminars to discuss the issue, but to no conclusive result.

p.45

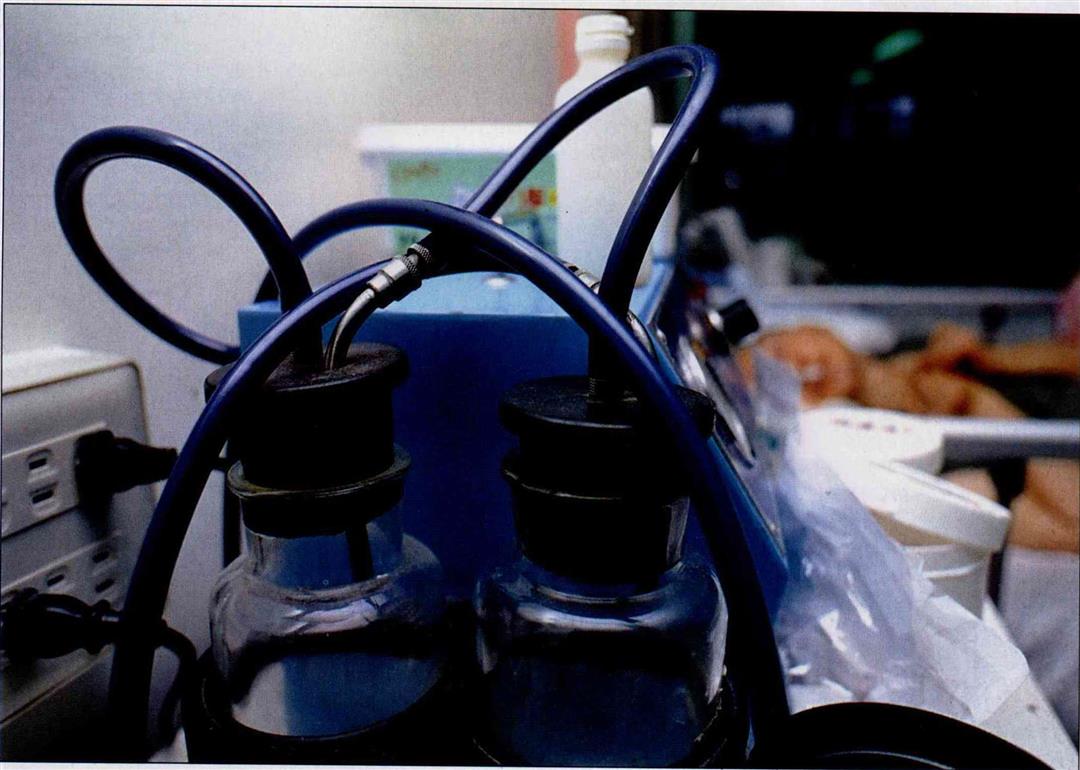

Where does one draw the line between life and death? Do respirators and other medical technology extend life, or merely the period on the brink of death?

p.46

Only when there is a complete social welfare system and people show the utmost respect for life will the preconditions for legalizing euthanasia be in place.

p.47

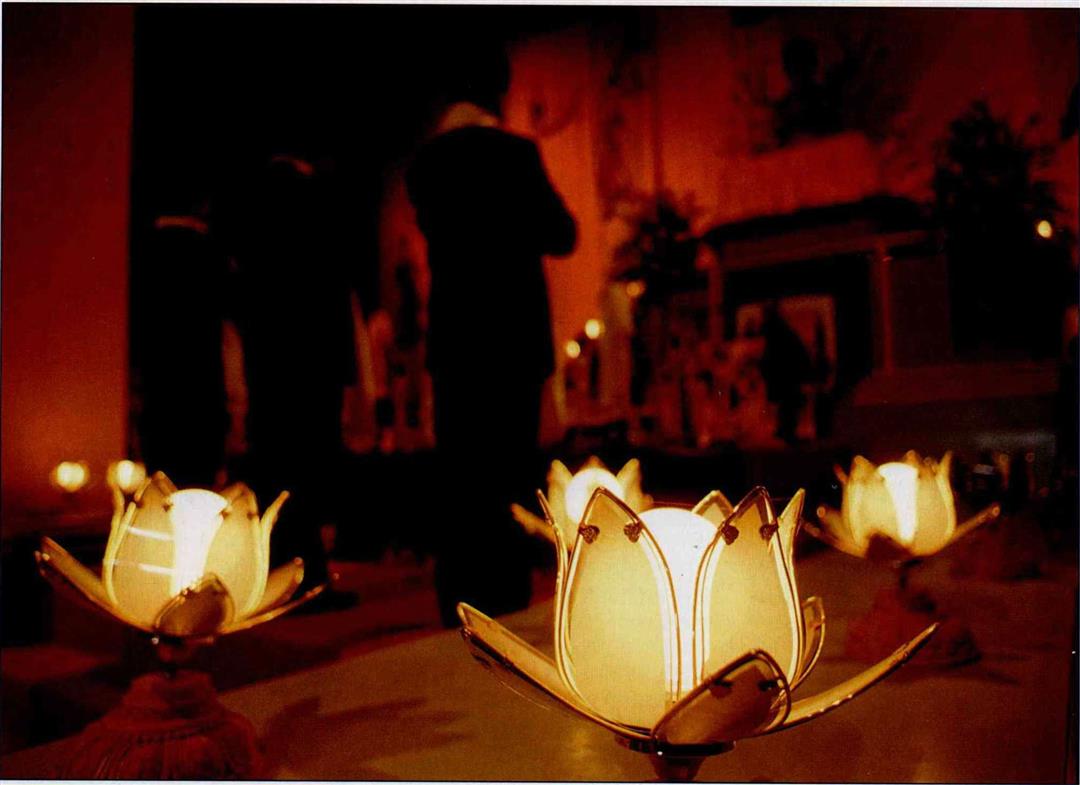

On the issue of euthanasia, Buddhists, though opposed to killing, have elected to remain silent. (photo by Pu Hua-chih)

Whether euthanasia should be legalized is a hard question that will always stir controversy. Over the last decade, the Creation Social Welfare Foundation has put on three seminars to discuss the issue, but to no conclusive result.

Where does one draw the line between life and death? Do respirators and other medical technology extend life, or merely the period on the brink of death?

Only when there is a complete social welfare system and people show the utmost respect for life will the preconditions for legalizing euthanasia be in place.

On the issue of euthanasia, Buddhists, though opposed to killing, have elected to remain silent. (photo by Pu Hua-chih)