The culture of the tattooed Atayal teeters at the brink of extinction here at the end of the 20th century, and many people are joining in the task of preserving it. We asked three very different individuals working on this task to share their reflections with us.

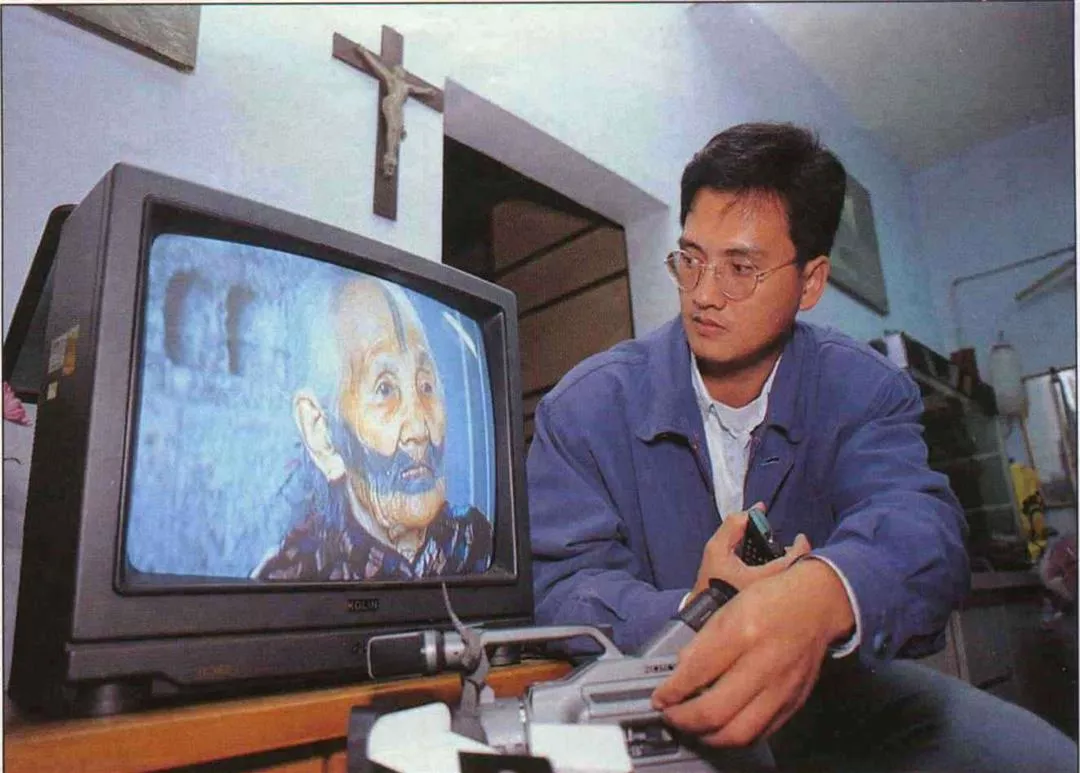

Ma Teng-yueh, a thirty-something cultural reporter, has already spent four years photographing the tattooed elders.

Why would he photograph these elders? Why study them and preserve a record of them? "Don't look at me for spirituality or moral purpose. I do it just because it's fun," says Ma, deadpan. Already regarded as the "most thorough" of those researching the elders, Ma has trekked to more than 200 tribal villages in Taiwan. In Taipei, relationships between people can be hurried and superficial, like an electric spark: "Today you meet and you're friends, tomorrow you meet again, and you don't always remember the other person," says Ma. "It's not like friendships in the tribes. Interpersonal relationships in the mountains have given me a feeling of real stability." Perhaps this is what attracted him to go to the mountains in the first place.

Ma Teng-yueh: Who are they?

During his college years, Ma Teng-yueh was in the mountaineering club. The destination for his first climb was the Ssumakussu village of the Atayal tribe in Hsinchu County's Chienshih Rural Township. In those days the village had no road to the outside world. Ma stayed there for several days, living and working alongside the people.

"At that time, we were only students, but living deep in the mountains, life was so hard for the Ssumakussu people. They brought out the best of all they had for us, and looking at their honest and simple faces, while we were very moved, we also felt ashamed and uneasy," says Ma. "Who were they? Where did they come from? What was their history? What were their lives and their culture like? Taiwan is not a big place-why did I feel such a stranger to others who were living with me on the same island?"

This feeling was what first led Ma to work to understand the Atayal culture in the days that followed. His ambition was do something to assist the Atayal, and he threw himself into the task. And the special characteristic of the Atayal people-facial tattoos-became a topic of Ma's intensive investigation. After spending more than four years photographing the Atayal tattoos and creating a record of his interviews with them, Ma Teng-yueh's most lasting impression of the work was that it had begun too late.

Ma explains that the Japanese had issued orders forbidding the practice of Atayal tattooing in the 1910s, but it was only around 1936 that a complete repression of all Atayal tattooing was effected. During this period, apart from a few Japanese anthropologists, such as Tori Ryuzo, who had come to Taiwan and who mentioned the tattooing culture of the Atayal in their letters and writings, it was not until after Retrocession that Academia Sinica researcher He Ting-jui did research on the tattooing cultures of all the peoples of Taiwan. However, even this work did not concern the Atayal directly. And it was only later, in the 1990s, that more people have become interested in the Atayal tattoos.

Meeting with history

The publication of He Ting-jui's research paper in 1960 did not postdate the era of Atayal cultural proscription by long. At the time, authentic materials and elders were both common. However, in the 1990s, as Ma and others take up the task, there are few old people left, and authentic materials are scarce. Moreover, the memories of the older folks have become clouded. All this creates difficulties for those wishing to understand the culture today. Also, as time marches on, the tattooed elders pass away at an ever faster rate. When Ma Teng-yueh was photographing five years ago, there were over 200 of these elders still living; today, there are not even 100 left in all Taiwan. Often, the photographs Ma develops and presents to the families of these old people soon become their funerary pictures. Ma's face takes on a regretful cast as he speaks.

In his years of photographing the tattooed ones, Ma's greatest joy was in letting more and more people, whether in the cities or the tribes, discover the traditional Atayal culture after seeing his photos in 1993.

"It's great when more and more people start to join in something really interesting, isn't it?" says Ma. He feels that his recording of the tattooed people allows him to feel a part of the "unbroken thousands of years" of Taiwan's history. Thinking of this, Ma felt that his own difficulties, like not being recognized by governmental organizations, frequent financial difficulties, and so on, paled in comparison.

Liu Kang-wen: Searching for answers

Last year, Hualien resident Liu Kang-wen won an award at the Taipei film festival for his documentary on the tattooed of his region. His film has been regarded as "very emotional; it is difficult for one who does not speak the language and who has not lived with the tribe for a long period to shoot this kind of film," says Chen Liang-feng of Full Scene Film/Video Studio.

Although only a brief 13 minutes in length, Liu Kang-wen's documentary film is extraordinarily warm from start to finish. For example, he captures a few old people tugging at each other's shirts, warning each other that they have to "look good for the camera." The daily lives of these elderly people can be vividly imagined through the questions they answer for Liu: Where are the best places to catch fish? What is your daily life like? Where do your children work? Do they come back to see you?

Liu Kang-wen works at Dong Hwa University in Hualien; he filmed his documentary on the Atayal during his free time. "Why film the old ones? Apart from the danger of this culture disappearing forever, and the short time left to record it, it's just the same way anyone is concerned with the affairs of his own area," says Liu. He says he was merely looking for some answers.

"Why are the Atayal going down like this?" Liu Kang-wen often ponders this question. In the past, the Atayal culture couldn't have been this fragile. "What we read in the histories recorded in textbooks seems a bit at odds with what the old people tell me," says Liu. "When I was filming the tattooed elders, I not only asked them about the tattoos, but also about their general situation in the past. Did they drink? What were relations like between the sexes? What were marriages like?" Through these interviews, Liu says that he has come to understand more about the lives of the Atayal in the past, but in comparing the past and the situation now, "which ones are the real Atayal?"

When Liu Kang-wen's documentary was exhibited in Taipei, it caused some response. People raved about his camera angles. Even more people asked him why he used light in a certain way, or whether it wouldn't have been better to shift the focal point of a scene. Liu, who is not a professional photographer, was hard-put to respond. He says that of course these questions aren't trivial, but in perspective, he preferred the response from the showings in Hualien. "The audience there would ask you what the people eat and how they live. I like these questions, because they allow more people to understand the tattooed elders. That was my purpose in making the film in the first place," says Liu.

At the Taipei screenings, one person from the audience mentioned an elder in the film talking about local traits. The old man had said something like "Those guys from Chiahsing, now they're not too particular. Over around Chilai Mountain, the ones from Maiyuan, they'll just take a piss anywhere they feel like it." Liu Kang-wen says that this was film of elders chatting, and that this was meant in a humorous way. Liu translated it literally for the film, not thinking that people would doubt the decorum of the Atayal culture as a result.

Liu didn't answer the man's question at the time, but he felt very strange about the incident afterwards. "Clearly, people are still clinging to their stereotypes about aboriginal peoples," he says. At the beginning, this made him quite sad, and he decided not to make any further documentaries, in order to avoid stirring up doubts in the "city folks." However, after he reflected longer, he decided that if he did not make more films, the gulf between people would only continue to deepen, and people, who were basically good, would only hurt each other, adding to a spiralling downward cycle. As a result, Liu has set out once again across the mountains, lugging the camera, to record more film.

Anli Ginu: What symbolizes the Atayal?

Anli Ginu, a graduate of Chinese Culture University who studied visual arts in New York, is himself an Atayal. In October of 1996, he had his own exhibition in a Taipei museum with tattooing as its theme.

Anli Geinu points out stories like "The Marriage of the Sister and Brother" and "Shunning Evil Omens" which depict Atayal who were unwilling to run away from difficulties, and bravely stood up to the challenges. The tattooing of the face is a very painful affair, but the Atayal are willing to bear it, and the custom has been passed down over generations. It is an expression of the vitality and dignity of the Atayal people. Anli Ginu tries to express these experiences on canvas, and hopes to be able to change today's urban stereotype of the Atayal as a poor and backward people. "Perhaps the face-tattooing culture of the Atayal can provide an opportunity for reflection," says Anli. This was precisely his reason for creating the works.

p.50

A crowd of people is gathered, and flashbulbs pop as everyone struggles to get a look at the "facial tattoo treasures." But what exactly is the meaning of facial tattoos? The picture shows the "Reminiscence of the Past" ceremony held in mid-October of last year in Tai-an Rural Township.

p.51

Ma Teng-yueh, who got his start as a journalist, has spent the last several years investigating the Atayal custom of facial tattooing. His field surveys are recognized as the most exhaustive.

p.52

Anli's paintings prominently feature the facial tattooing and apparel of the Atayal, attempting to draw forth the symbols of the Atayal people.

p.53

Liu Kang-wen's camera records the old Atayal ladies, along with his own emotions and doubts.

Liu Kang-wen's camera records the old Atayal ladies, along with his own emotions and doubts.