As the lights slowly dimmed, the clear, crisp, resonant sounds of Chinese flutes and drums under the direction of master musician Li Hsiang-shih began to set the mood for the performance of an episode from the Nankuan opera Ch'en San and Wu Niang.

Nankuan opera, also called Plum Garden opera, is a form of opera that originated in the Chuanchou region of Fukien Province and entered Taiwan in the seventeenth century. The dialogue is spoken chiefly in the ancient pronunciation of the Chuanchou dialect, and the lyrics are elegant, classical, and infused with poetry. The gestures are graceful and refined and governed by strict rules. Nankuan opera, the oldest form of opera in the Fukienese system, is believed to preserve many features of dramatic opera from the Sung (960-1279) and Yuan (1271-1368) dynasties.

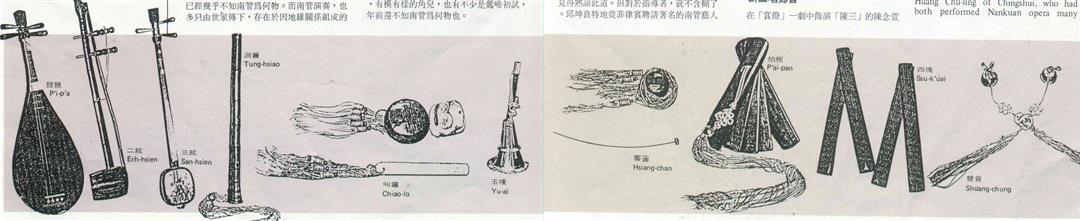

The music accompanying the opera, called Nankuan music, also originated in the Chuanchou region. The main instruments, called the ten sounds, are the tung-hsiao, a deep, full-sounding recorder; the p'i-p'a, or balloon guitar; the erh-hsien, a two-stringed fiddle held vertically and played with a bow; the san-hsien, a three-stringed lute; the ssu-k'uai, a double pair of wooden clappers fastened at the top; the shuang-chung, or double bells; the hsiang-chan, or resonating cup; the chiao-lo, or sounding gong; the yu-ai, a short oboe; and the p'ai-pan, five wooden clappers fastened at the top.

Nankuan music is classic, austere, and refined; its melodies remote and distant. The melodies have the same names as those of the ancient northern and southern songs (ch'u), and the way they are played is believed to preserve many of the features of music from the T'ang (618-907) and Sung dynasties.

In order to help restore this gradually waning form of Chinese opera to its previous vigor, the National Theater asked the Center for the Traditional Arts at the National Academy of the Arts to plan and direct a series of Nankuan opera activities, including the selection and training of performers, seminars, performances, and audio recordings.

Says chief planner Ch'iu K'un-liang: "What we hoped for with our plan is not to produce a single professional-level performance but rather to explore the adaptability of folk opera to the contemporary stage and the means to preserve it, develop it, and pass it on to future generations." For that reason the performers selected were mostly student musicians interested in the music but not necessarily familiar with playing it.

Towards the conductor and director, however, Ch'iu was much more choosy. He specially asked the noted Nankuan artist Li Hsiang-shih, who lives in the Philippines, to serve as music conductor, and he invited Wu Su-hsia of the Chingshui Chingya Conservatory to serve as voice and acting director. The chief accompanists included several performers with a strong background in Nankuan music from the Tainan Nansheng Society, the north, and the central parts of the island. In addition to the students who were getting their first taste of Nankuan music, the leading roles were taken by Shih Jui-lou of Lukang and Huang Chu-ling of Chingshui, who had both performed Nankuan opera many times.

After more than two months of practice, the students put on the first performance of Nankuan music this July in front of the Paoho Temple in Luchou, accompanying a series of folk performers such as lion dancers, stilt walkers, and masked mummers.

After their performance at the National Theater this October, the students can rest for the time being. But they will perform on a more formal recital in the main hall of the National Theater in January.

If you want to find more about Nankuan opera and encourage the preservation of this refined and beautiful tradition, why not go there and join them?

[Picture Caption]

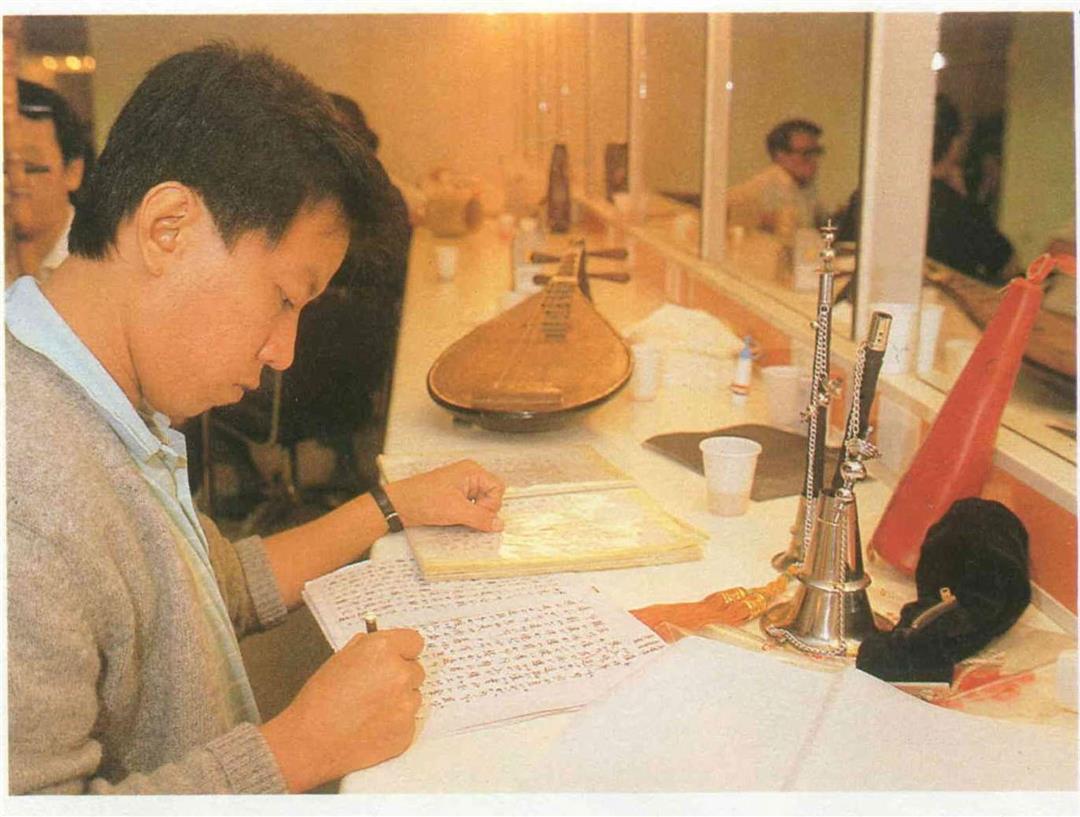

With limited prior exposure to the music, the students had to practice hard.

Study how a master does it!

The lantern episode from Ch'en San and Wu Niang offers humor and romance.

The background ensemble.

The roles of Yi-ch'un and Ch'en San were well sung and acted, holding promise that the next generation of performers will carry on the tradition in fine form.

P'i-p'a Erh-hsien San-hsien Tung-hsiao Chiao-lo Yu-ai

Hsiang-chan P'ai-pan Ssu-k'uai Shuang-chung

Woodwind player Wang Wen-huan, who was invited from the Philippines, adjusts his score.

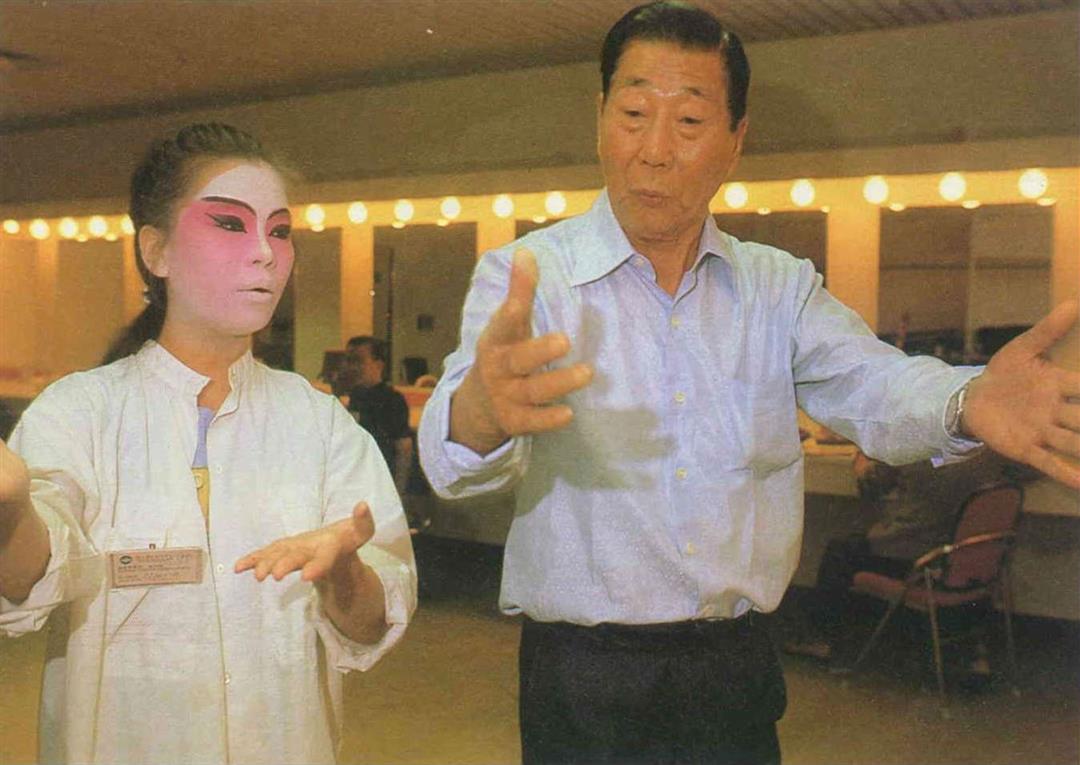

Wu Su-hsia (left) from Chingshui is a consummate artist with exquisite gestures.

Ch'iu K'un-liang (second from right) chats with musicians in a courtyard at the Center for the Traditional Arts.

The lantern episode from Ch'en San and Wu Niang offers humor and romance.

Study how a master does it!

The lantern episode from Ch'en San and Wu Niang offers humor and romance.

P'i-p'a Erh-hsien San-hsien Tuan-hiao Chiao-lo Yu-aiHsiang-chan P'ai-pan Ssu-k'uai Shuang-chung.

Woodwind player Wang Wen-huan, who was invited from the Philippines, adjusts his score.

Wu Su-hsia (left) from Chingshui is a consummate artist with exquisite gestures.

Ch'iu K'un-liang (second from right) chats with musicians in a courtyard at the Center for the Traditional Arts.