Europe has recently become a very popular destination for tourists from Taiwan, but when they visit museums and palaces and see Chinese trinket cabinets inlaid with gold and mother-of-pearl, entire walls painted in Chinese lacquer and roomfuls of Chinese porcelain, they can't help thinking back to the last dynasty and muttering: "But this was all stolen from China!"

In fact such criticism is often misguided, as such European buildings date from well before the late nineteenth century and the destruction of the Ch'ing imperial palaces by the Joint Expeditionary Force. Yet these objects are no genuine collector's items either; so just what is their origin?

If you look closely, even people unfamiliar with Chinese art history will usually discover a number of curious anomalies.

The figures in these "Chinese paintings" with their full cheeks and prominent noses look for all the world like westerners who have strayed into the Prospect Garden; dragons look like serpents, phoenixes like geese; and to cap it all, the "Chinese characters" turn out to be nothing but farragos of random lines.

So the truth is out--these are just imitation pieces, examples of the Chinoiserie style popular in Europe two or three centuries ago.

European contact with China goes back to its first discovery of the Orient, brought about by improved navigation thanks to the introduction of the magnetic compass. Marco Polo's legendary tales of his travels to China inspired visions of a paradise in the East. East-West trade was later opened up by the East India Company, founded in the seventeenth century, at a time when Chinese handicrafts were at their peak Shipments of fine Chinese porcelain, silk and furniture reaching Europe were snapped up as marvels by royal families and the aristocracy.

As British scholar Hugh Honor points out in his book "Chinoiserie", one important reason for the eventual shift away from genuine imported items towards imitation goods was that supply failed to match demand. Chinoiserie items are little in evidence in Spain or Portugal, both of which had large fleets and close trading links with China.

Also, according to Professor Wang Chien-chu of National Taiwan Normal University's Department of Fine Art, certain goods had to be copied locally for practical reasons.

"Europeans were fascinated by things Chinese, but they found them unsuitable for use," Wang explains. Chinese bowls, for example, were useless for western dining tables, and Chinese teaware was hardly suitable for coffee. . . . So Europeans began ordering specially-made export ware from China, and eventually, as local porcelain manufacture matured to perfection, oriental china was copied in Europe itself.

Interestingly, with the trade balance vastly in China's favor, European manufacturers, fuelled by protectionist sentiment, decided to fight back against the competition of exports from the East. Instead of raising tariffs, they copied Chinese goods. Some craftsmen grew adept at Chinese-style designs and became leaders of a new contemporary trend.

Thus we find European Chinoiserie interiors, furniture, porcelain, textiles and gardens carefully designed to imitate the Chinese manner, however errantly, together with masterpieces of oriental pastiche executed using western techniques and based on Chinese inspiration.

The earliest example of a complete interior based on Chinoiserie designs is to be found at the Trianon palace in the grounds of Versailles, built for a favorite by King Louis XIV in 1670.

Later the fashion for Chinoiserie spread like wildfire, with craftsmen in Austria, Poland, Russia and Scandinavia creating their own "Chinese dreamscapes" on the basis of English and French engravings. No wonder that visitors walking into the "Chinese rooms" in royal palaces all over Europe are often struck of deja-vu.

Such 200-year-old copperplate prints proved invaluable in restoring the many Chinoiserie interiors damaged during the Second World War. A collection of them survives at the Kaltenberg palace in West Berlin, and thanks to careful conservation these fine engravings on yellowing paper preserve all the original atmosphere of Chinoiserie in lucid and fascinating detail.

Generous use of gilding and lacquerwork, a fondness for blue and white contrast, rejection of western perspective and the adoption of Chinese-style layout and motifs are the hallmarks of Chinoiserie, which at heart was a mixture of the Baroque and Rococo art styles popular at the time.

Commonly occurring Chinese creatures and plants found in such paintings include dragons, phoenixes, cranes, gibbons, plantains, bamboos and rushes, often coexisting side by side with the shells, waves and vines typical of the Baroque and Rococo styles.

Other popular Chinese elements include pagodas, pavilions, balustrades, fans, umbrellas, bamboo-leaf hats and Chinese musical instruments. As for human figures, we find "Chinese" women with European hairstyles and Ch'ing dynasty mandarins sporting streaming pigtails, together with a plethora of farmers, fishermen, children and servants.

"In these paintings we tend to find that whereas things of nature such as flowers and trees are painted accurately, a false chord is struck as soon as the painter turns to anything cultural or tries to portray things that form part of the Chinese way of life," notes Wang Chien-chu, hitting the nail on the head.

The reason for this is that very few Europeans had ever visited China at that time, and everyone depended on hearsay. The only genuine Chinese articles most westerners had seen were albums of paintings, porcelain or furniture shipped back by the East India Company.

Sometimes western artists portrayed Chinese elements but used them in an odd way, such as showing a pigtailed Chinese blowing a western trumpet on a European-style fortification. Sometimes the proper uses of Chinese objects were not understood, such as mistaking a spittoon for a flower vase.

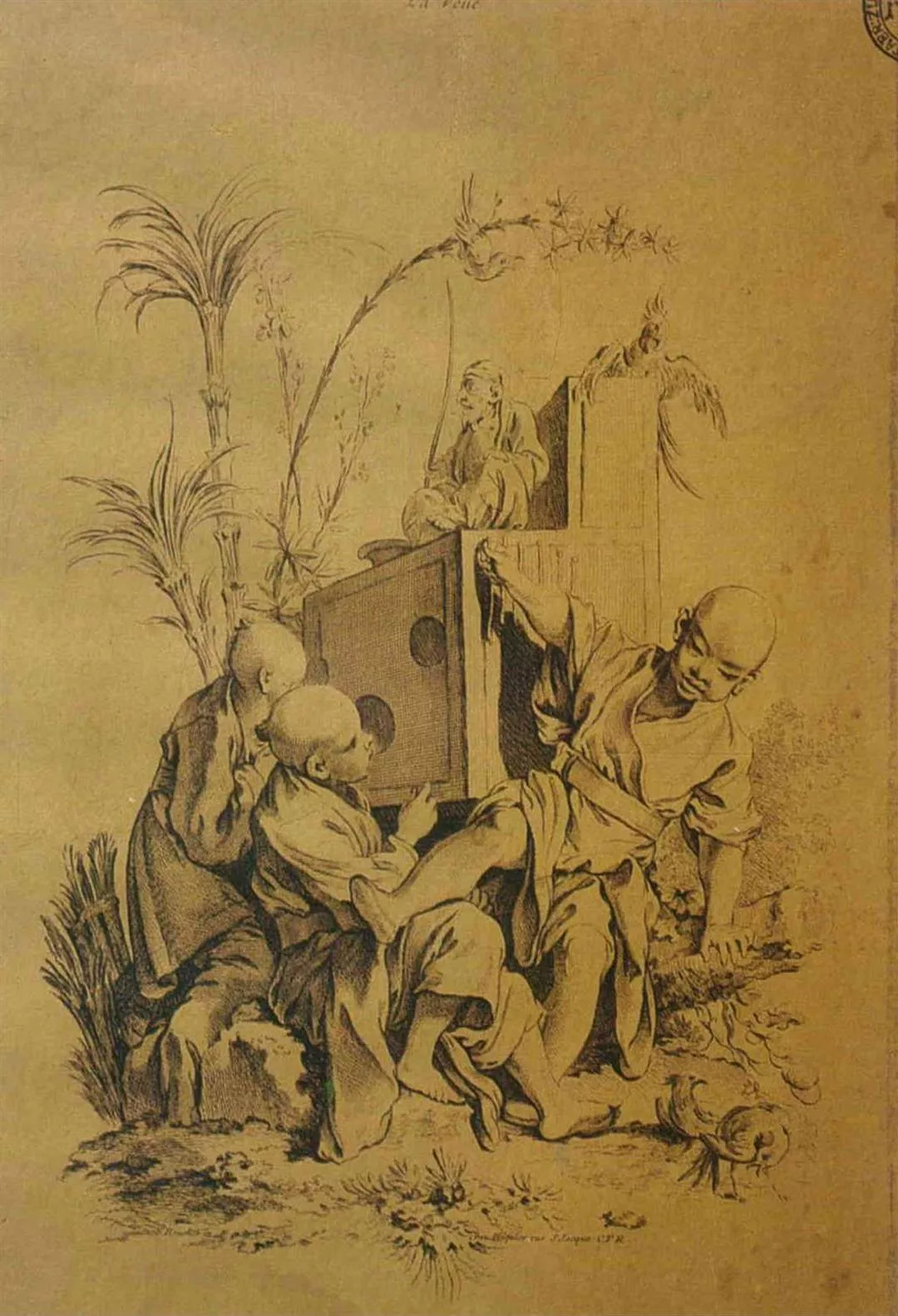

While the actions being performed by "Chinese" figures may have seemed mysterious to westerners, they look no less mystifying to today's Chinese visitors! A classic Chinoiserie engraving of 1719 by the French artist Watteau shows a woman seated in the centre holding a paper umbrella in one hand and a long-handled feather whisk in the other, while bald-headed attendants with drooping moustaches and tall hats bow reverently on either side.

Apparently this scene was painted by Watteau after a Chinese album presented to Louis XIV by the Jesuits. But several mistakes have crept in along the way. While the Chinese do use feather fans, the type of feather whisk shown here was only used as a duster, and would only have been handled by a servant. Also, oiled paper umbrellas were of Japanese origin, but Europeans often failed to distinguish between things Chinese and things Japanese.

Another fundamental problem for western artists was their lack of experience in Chinese painting techniques. "As soon as you try depicting a Chinese scene using western painting methods, the effect goes awry," Wang Chien-chu observes. Further copies based on such flawed originals tend to look even more unnatural.

But this kind of thing can happen in every culture, and perhaps we shouldn't take it too much to heart. The K'ang-hsi Emperor knew how to appreciate the joke. He seems to have taken a particular liking to a French Chinoiserie tapestry presented to him by Louis XV, which of course stood out a mile as not being remotely Chinese. But the emperor's fondness for the French mood of the scene became clear near the end of the dynasty when the Joint Expeditionary Force stormed the Forbidden Palace and discovered this very tapestry neatly hanging on a palace wall.

[Picture Caption]

With its dragon's head, eagle's body, tiger's paws and serpent's tail, this extraordinary Chinoiserie dragon is perched on a motif resembling shells and waves at once. The magnificent and grandiose style indicates that this is a typical work of the Baroque period.

(Below right) The woman in this picture looks part Japanese, part western, but not Chinese in the least.

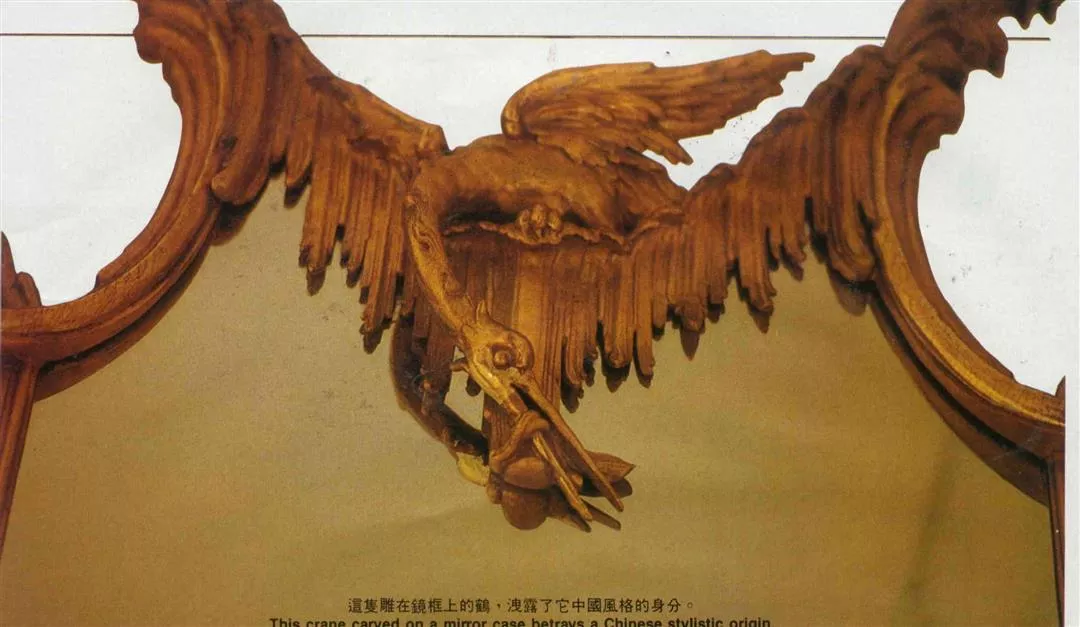

This crane carved on a mirror case betrays a Chinese stylistic origin.

(Left) Tea is Chinese and no mistake, but who knows where the "Chinese characters' beneath the Buddhist figure come from?

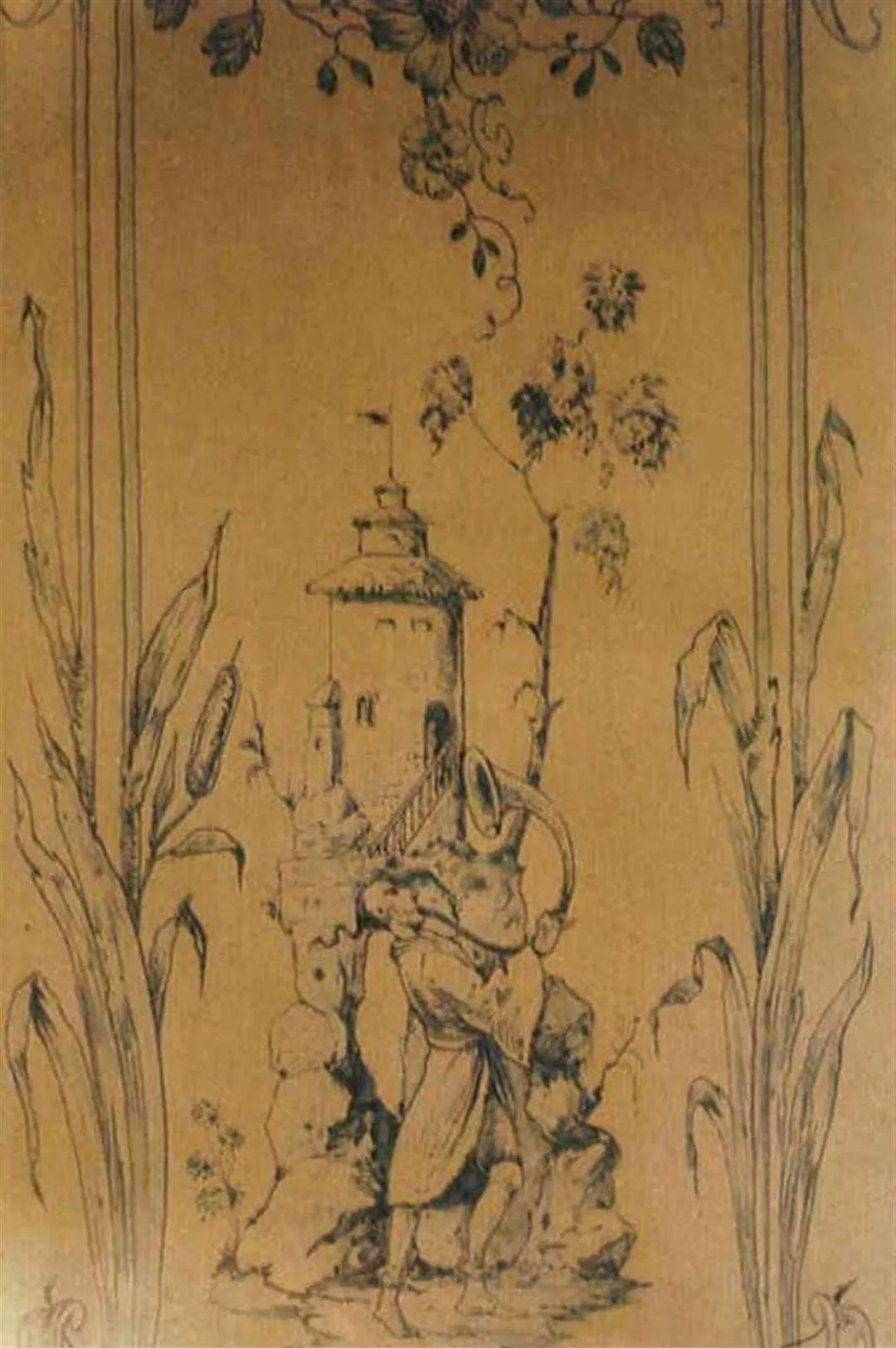

(Below) This Ch'ing dynasty figure shown blowing a trumpet seems to have gone overboard for the western way of life!

Abstract these figures may be, but the work of these western Chinoiserie artists is nevertheless touchingly attractive.

(Left) This painting abounds in Chinese 'elements', although the use of western artistic techniques unavoidably creates a false note.

(Below) This painting photographed at West Berlin's Kaltenburg Palace is very similar to a Watteau Chinoiserie engraving of 1719, except that the woman is holding a fan instead of an umbrella.

Apes are one of the most commonly portrayed animals in Chinoiserie.

(Below right) The woman in this picture looks part Japanese, part western, but not Chinese in the least.

This crane carved on a mirror case betrays a Chinese stylistic origin.

(Left) Tea is Chinese and no mistake, but who knows where the "Chinese characters' beneath the Buddhist figure come from?

(Below) This Ch'ing dynasty figure shown blowing a trumpet seems to have gone overboard for the western way of life!

Abstract these figures may be, but the work of these western Chinoiserie artists is nevertheless touchingly attractive.

(Left) This painting abounds in Chinese 'elements', although the use of western artistic techniques unavoidably creates a false note.

Apes are one of the most commonly portrayed animals in Chinoiserie.

(Below) This painting photographed at West Berlin's Kaltenburg Palace is very similar to a Watteau Chinoiserie engraving of 1719, except that the woman is holding a fan instead of an umbrella.