The Satellite Village of Asia's Chinese--Star TV's Chinese Television Station

Hsieh Shu-fen / photos Huang Li-li / tr. by Christopher Hughes

March 1993

The traditional dragon and lion dances performed during this year's Spring Festival celebrations at the Great Wall of China were accompanied by the pop song China Rock and Roll by the singer Chao Chuan from Taiwan. As people held candles during a chorus with a symbolic passing on of a torch, the Hongkong song Pearl of the East was adapted into an anthem. Artists from all over the place were buzzing to-and-fro like flies to give their performances. It was a very exciting scene.

No, the two sides of the Taiwan Strait had certainly not been unified. This was nothing more than the program New Year's Eve Reunion for the Four Areas (mainland China, Taiwan, Hongkong and Singapore) organized by Star TV's Chinese station.

This power of broadcasting to break through national borders and distances has already frequently rubbed up against regulations and policies for broadcasting on both sides of the Taiwan Strait. So what kind of influence is it going to have on Asia's Chinese?

Do you still remember those days, 20 years ago, when the whole family would eat instant noodles sitting all night in front of the television to keep up with the situation in the Little League by relayed broadcast? Although Taiwan and the United States are separated by more than 20,000 kilometers of Pacific Ocean, not only did satellite relay enable us to see images of the brilliant performance of Taiwan's young baseball players in America, we could even join the overseas Chinese and students in the stadium in rapturously egging them on. From then on people in Taiwan knew all about the pulling power of satellite broadcasts, irrespective of distance.

In April, 1990, mainland China's Long March 3 rocket was used to launch Asiasat 1, its first satellite for commercial use. After one year the Star TV Network was established by Hongkong's Hut-chison Whampoa group and began broadcasting through Asiasat 1. Star TV's five channels (Chinese, music, sport, family entertainment and BBC news) now beam programs direct, 24 hours every day, to all areas of Asia.

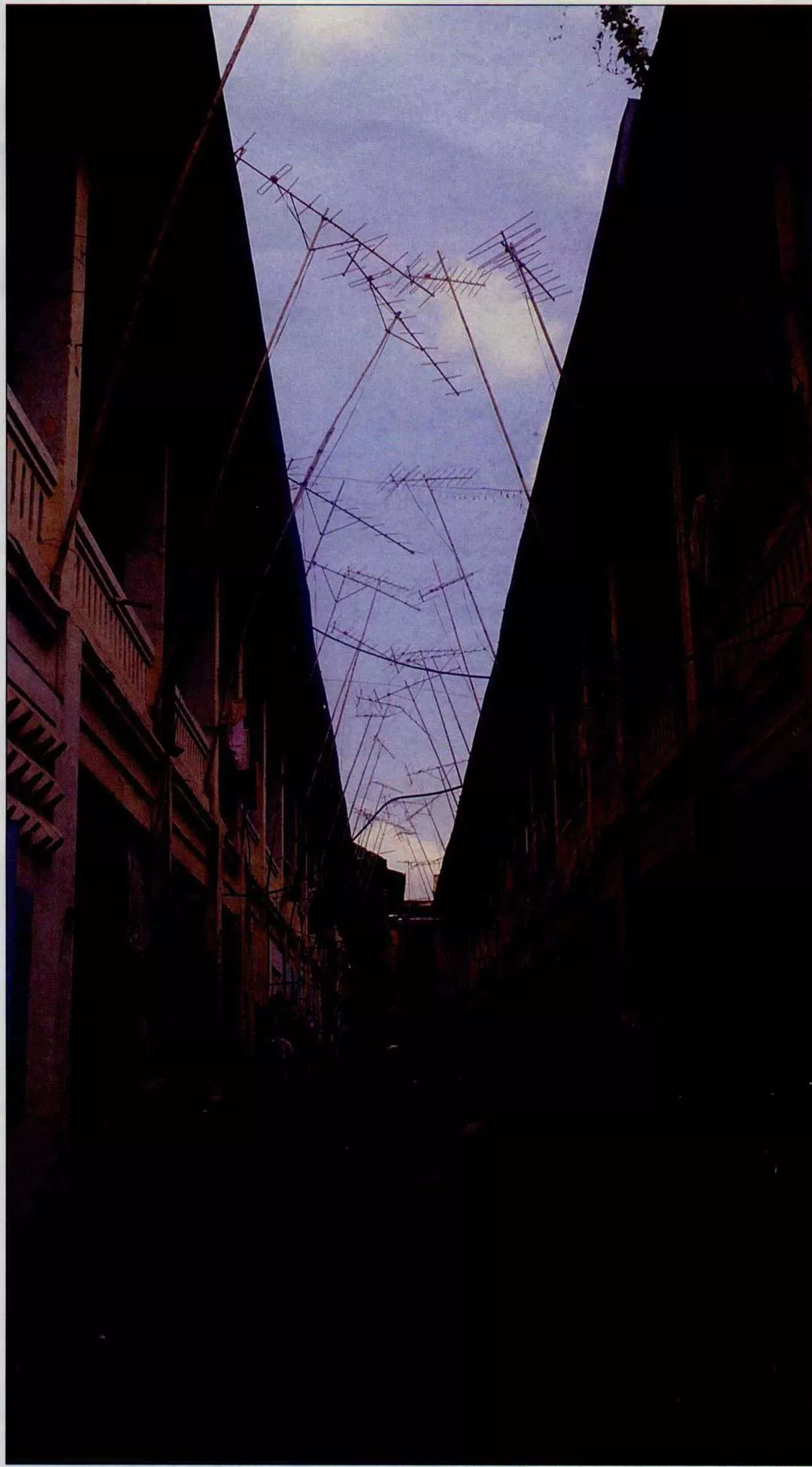

Through satellite dishes information from abroad can cross borders and boundaries.

A greater-China "television village"?:

Of course the English language, pop music, mini-series and sports entertainment channels were just right for the needs of the rising Asian market; but what drew people's attention even more than these was the Chinese station.

Mainland China, Taiwan, Hongkong and Singapore hold the main concentrations of Chinese people in the area. There are also many Chinese in Japan, Korea and Southeast Asia. Chinese make up four-tenths of the overall population and approach 1.2 billion in numbers. However, before the appearance of Star TV, there was not one Chinese channel among all the satellite television channels beamed direct to Asia.

Although the Chinese of Asia share the same language and are of the same race, for a long period political, linguistic and nationalistic barriers have divided them. The great broadcasting power of television was especially fenced in, as with between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait, where political actors meant a minimal exchange of programs. In the countries of the overseas Chinese of Southeast Asia, such as Malaysia and the Philippines, Chinese programs would be severely constrained by time restrictions.

By leading the way in including Chinese language programs in its direct satellite broad-casts, Star TV broke the previous situation in which the comparatively advanced broadcasters of Europe, America and Japan had taken the lead, and became Asia's first media service for the Chinese speaking area.

When Star TV began broadcasting, Time magazine predicted that the international programs it would beam out would constitute a big challenge to the countries of Asia, with their comparatively conservative broadcasting environment.

Star TV had not even be broadcasting for two years when the startling growth in its ratings and fame meant that the power of its influence over Chinese people in all areas began to be revealed.

Taiwan's three network stations are an important source of programs for Star TV.

Studying Mandarin:

In Taiwan, Star TV has already become the main channel for viewers watching programs from mainland China, Hongkong and Japan.

As for the spread of Star TV in Asia, last year the Tourism Bureau of the ROC Ministry of Transport and Communications for the first time produced a programme on the Lantern Festival with the idea of giving the exclusive broadcasting rights to Star TV in the hope that this would attract tourists from overseas.

Overseas Chinese tourists from Korea now come to Taiwan singing Taiwan's latest popular songs on their coaches, songs they have learned from Star TV's Chinese station's karaoke program. Meanwhile, Hongkong audiences are using the station to study Mandarin Chinese.

It has also become an important source of entertainment for Hongkong businessmen in Taiwan, and Taiwanese businessmen in the Philippines.

Mr. Chung's family, who only came from Hongkong to live in Taiwan last year, spends most days trying very hard to adjust to Taiwan's lifestyle. Watching Hongkong programs on Star TV in the evening or listening to the Cantonese of the Hongkong stars helps them to overcome the tension of being in another country amid their loud laughter. Following her parents to go and live in Manila, Su Pei-chen, now in her third year at university, says that the soap operas and arts programs on Star TV's Chinese station are a major topic of conversation for Chinese students there.

For the mainland China audience, who have always been strongly drawn by the pop stars of Hongkong and Taiwan, seeing the idols who were previously just sounds without bodies leads them to excitedly send in their song requests to Star TV.

Whether or not foreign programs should be allowed into every home with absolutely no screening is a matter which is still being argued about all over the world.

Breaking political barriers:

Such might well be the case. But wanting to broadcast to Chinese homes in every corner of Asia is still no easy thing.

"Many Asian countries think that satellite television is a kind of cultural invasion. They are afraid that as soon as values and information from outside come in through this avenue their native traditions and cultures will be thrown into confusion. Perhaps it will create racial divisions, destroying religion, politics and art. They thus frequently use social stability as a reason to impose restrictions," says Chen Wen, a lecturer in journalism and broadcasting at the Chinese University of Hongkong.

In a research paper on the reaction and reception of satellite television by Asian countries, Chen points out that the attitudes held by Asian countries towards satellite television can be divided into four main categories: complete prohibition, conditional openness, nonlegal openness and prohibition without the ability to control.

Comparatively strict Singapore and Malaysia, for example, prohibit the import and manufacture of receiving equipment. This has been effective in stopping Star TV programs from getting in.

Hongkong, where the head office of Star TV is located, is an example of conditional openness. So as to protect the competitiveness of local terrestrial and cable television stations, the Hongkong government has stipulated that Star TV cannot broadcast in Cantonese for its first three years of operations and cannot collect subscriptions from the cable television that relays its programs. Although the three years is nearly up, it is still only the news, sports and music stations which have been freed, while the Chinese station still cannot broadcast in Cantonese. This has been a great hindrance for their ratings.

Taiwan and mainland China belong to the last two categories respectively.

The situation of satellite reception varies greatly between the countries of Asia: the R.O.C. permitted the installation of "small ear" receivers (above) four years ago; in Vietnam (facing page), where economic recovery has just begun, they are forbidden and the people have no means to install them.

Taiwan's "Channel 4":

Taiwan certainly does not forbid direct satellite broadcasting. In 1989 the government allowed people to manufacture and install "small ears," as small dish receivers are colloquially called. This means people can watch Japanese and English programs on Japan's NHK. Last year, middle and large dish receivers were also allowed to be used for the reception of programs from Asiasat 1 channels.

Because the medium and large receivers are comparatively expensive and most families cannot install them for themselves, they are usually installed by communities or programs are relayed through cable.

What is rather embarrassing though, is that although the medium and large receivers can already be imported, the bill for cable television has not yet gone through the legislature. It is thus that satellite television, in lacking clear legislation, falls under the category of "nonlegal openness." With a situation in which private cable television is flourishing, satellite is also rising on its back. This is especially the case for the Chinese stations which have become the "Channel 4" alternative to Taiwan's three network stations.

According to Star TV's statistics, when broad-casting began last year the size of the audience that could receive satellite television was one million. In January of this year they commissioned a market research agency to do a report, the results of which showed a jump to over 1.9 million, a near doubling of the audience. In other words, one home in three receives satellite television.

Although the three network stations are sceptical about these figures, the director of the Government Information Office's (GIO) Radio and Television Affairs Department, Yen Jung-chang, takes the main target of satellite television, which is cable viewers, to make his calculations: At present, three in ten homes have cable television. Add to this some entrepreneurs who have installed their own medium-sized receivers and the figures are about right.

The Chinese Communists have adopted an attitude of complete prohibition of satellite television, restricting it to a few international hotels and special foreign business areas. Yet with the huge population of mainland China being somewhat beyond the whip of the center, in a very short space of time the number of families receiving satellite television has jumped to more than four million. This audience is spread mainly in the richer coastal areas, as well as inland provinces like Yunnan and Kweichow where the geography makes broad-casting without satellite impossible.

Up against broadcasting regulations:

Embracing the high acceptability of popular culture and completely taking the market as its lead is Star TV's strong point.

The flourishing of Star TV's Chinese station in Taiwan, apart from its language being the same as Taiwan's Mandarin, is also due to the advantage of satellite being a trans-border medium. For government organizations that cannot control companies in other countries, however, this has created a difficult case of double standards. "Since the arrival of satellite programs, there have been clashes with our television broadcasting regulations in many areas," says Yen Jung-chang.

This situation has enabled satellite broadcasters to exploit grey areas of the law to win audiences. For example, Taiwan's three television stations are regulated by laws: Programs broadcast to areas such as mainland China, Hongkong and Japan are all limited in terms of time and content. Star TV, however, is subject to absolutely no such restrictions.

An example is Japanese films. The government has stipulated that, apart from broadcasts of films that have already been shown in Taiwan, no Japanese programs are allowed. Star TV, being beyond the reach of the law, last year doubled its ratings by broadcasting a Japanese soap opera dubbed into Mandarin.

Programs from mainland China have also been in heavy demand by Taiwan's audience. According to regulations, television is at present only allowed to screen programs from the mainland which were made there by visiting organizations from Taiwan. Programs and films made by mainland organizations themselves are still not permitted. But thanks to Asiasat's Chinese station, viewers can now watch mainland-made films every day.

As well as this, things such as the much-loved Hongkong dramas, which are limited in quantity and time on the Taiwan networks, are naturally used fully by the unrestrained Star TV as a great attraction.

Star TV is still operating under a low price strategy to open up the route for advertising. When Star TV first tried broadcasting, its development was closely monitored and compared by Ogilvy & Mather Advertising. For example, the three domestic networks ask NT$90,000 for a thirty-second slot at peak time, and there is not much of that time to go around, making it hard to arrange a time or coordinate with other advertisements. Star TV only asks for NT$25,000 and is not subject to such limitations.

Only when satellite television from abroad is both sensational and compatible with audience tastes can it penetrate the market.

The effect of the global village:

Yen Jung-chang says that when the cable television bill is passed by the Legislative Yuan, control of this major relay system will be a basis for management and Star TV can hope to get a legitimate status.

"The reality of high ratings might force regulatory policy to move away from nonlegal openness towards limited openness," is the opinion of Chen Wen. Looking at it in the long term, the trend of the policy of the Chinese Communists might be similar to that in Taiwan, with a gradual opening up.

"Such is the efficacy of the global village that has been created by broadcasting technology," says director-general of Star TV, Chen Chen-hsiang. Perhaps it is a bit of an exaggeration to use the term "global village." Yet as Asia's first media dedicated to the Chinese area, it is hard to avoid having people getting rather high hopes about Star TV being able to bolster a little the ability of Asia's Chinese to come together.

Nevertheless, "Listening to the same pop songs, watching the same stirring soap operas, worshipping the same idols, cannot but be effective in reducing barriers and enabling communication," is the view of Wang Hsiao-hsiang, general secretary of the preparatory committee for public television.

Associate professor of National Chengchi University's department of journalism, Feng Chien-san, also points out that what is really needed to sweep away barriers and misunderstandings and establish consensus is to open up sincere and public debate and to report on all countries' political problems and public affairs. "However, because Star TV wants to avoid angering the closed psychology of the governments concerned, such things cannot be mentioned."

How to escape from these psychological shadows will be the biggest challenge for Asiasat as it comes up against the governments of Asia.

[Picture Caption]

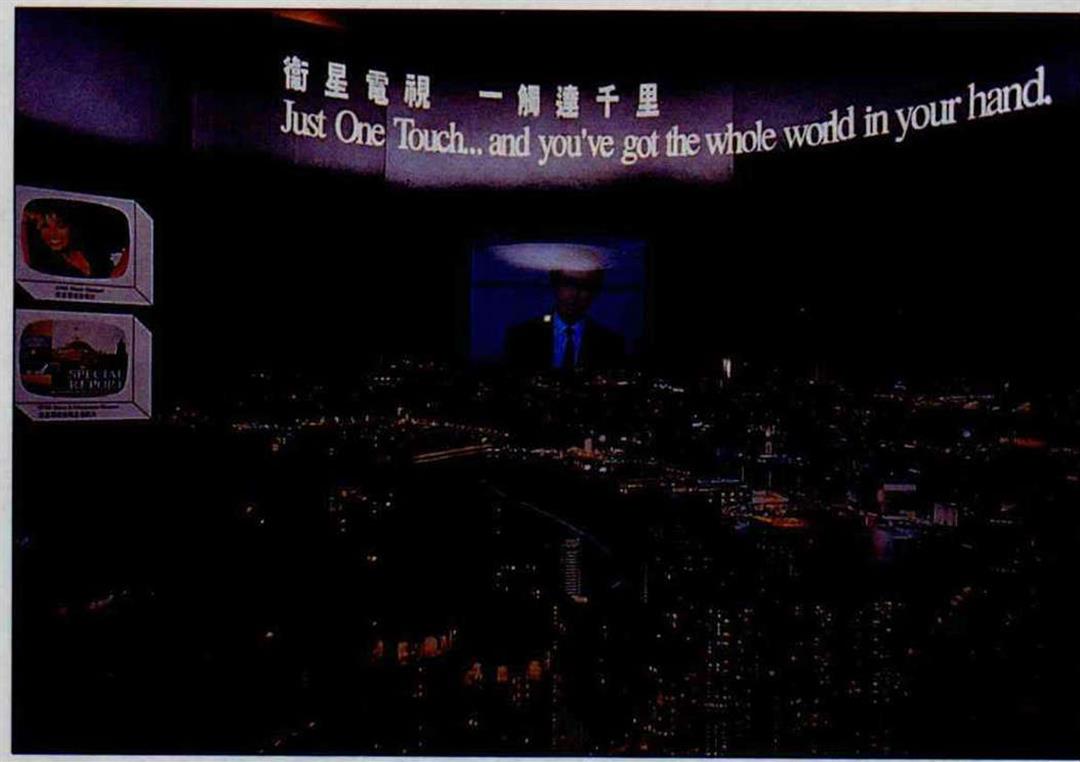

p.112

Breaking the restrictions imposed by distance, having the whole world in your hand, is one of mankind's dreams and the reasoning behind the appearance of satellite TV. (photo by Diago Chiu)

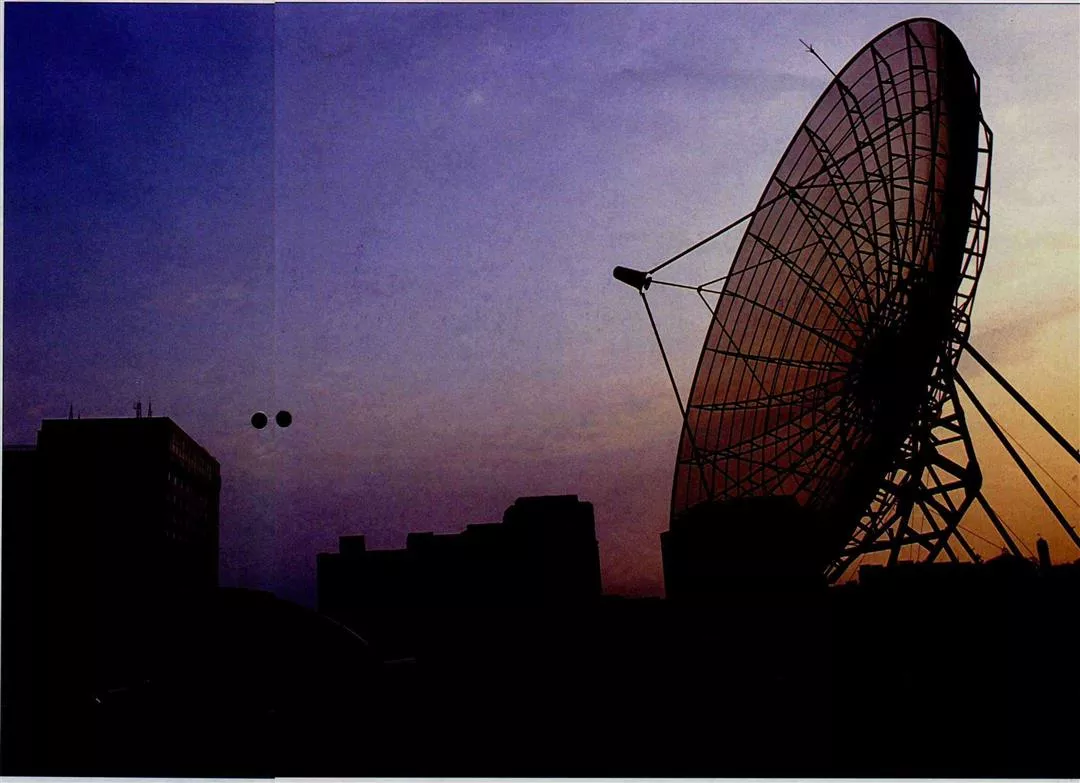

p.113

Through satellite dishes information from abroad can cross borders and boundaries.

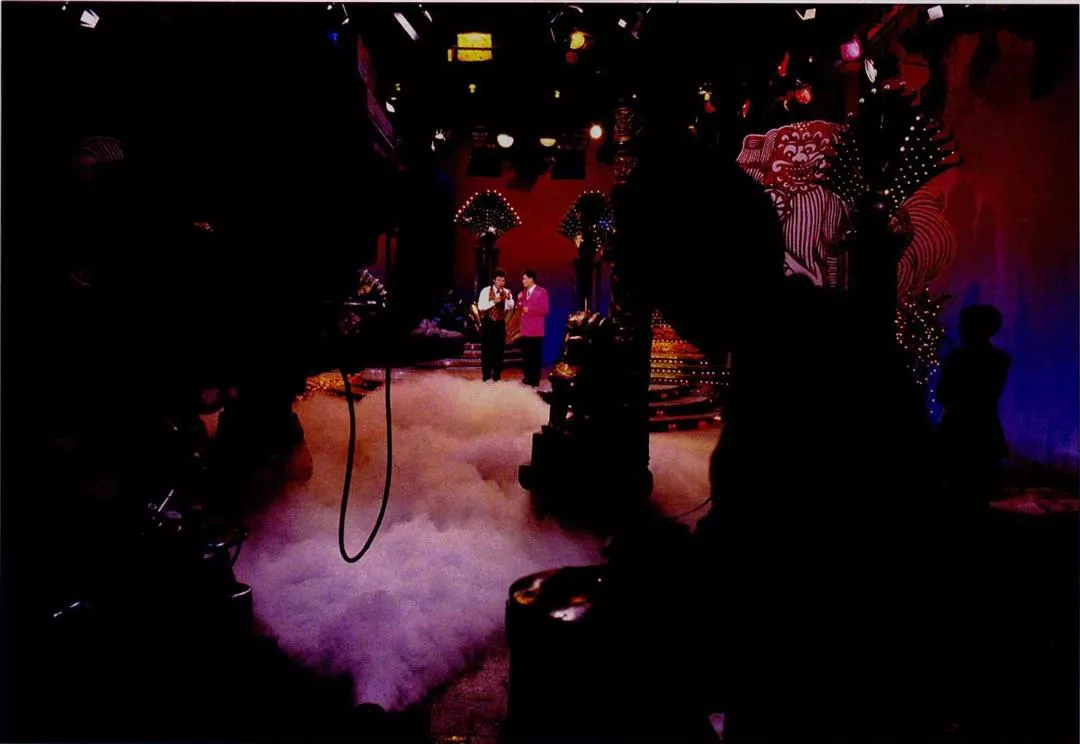

p.114

Taiwan's three network stations are an important source of programs for Star TV.

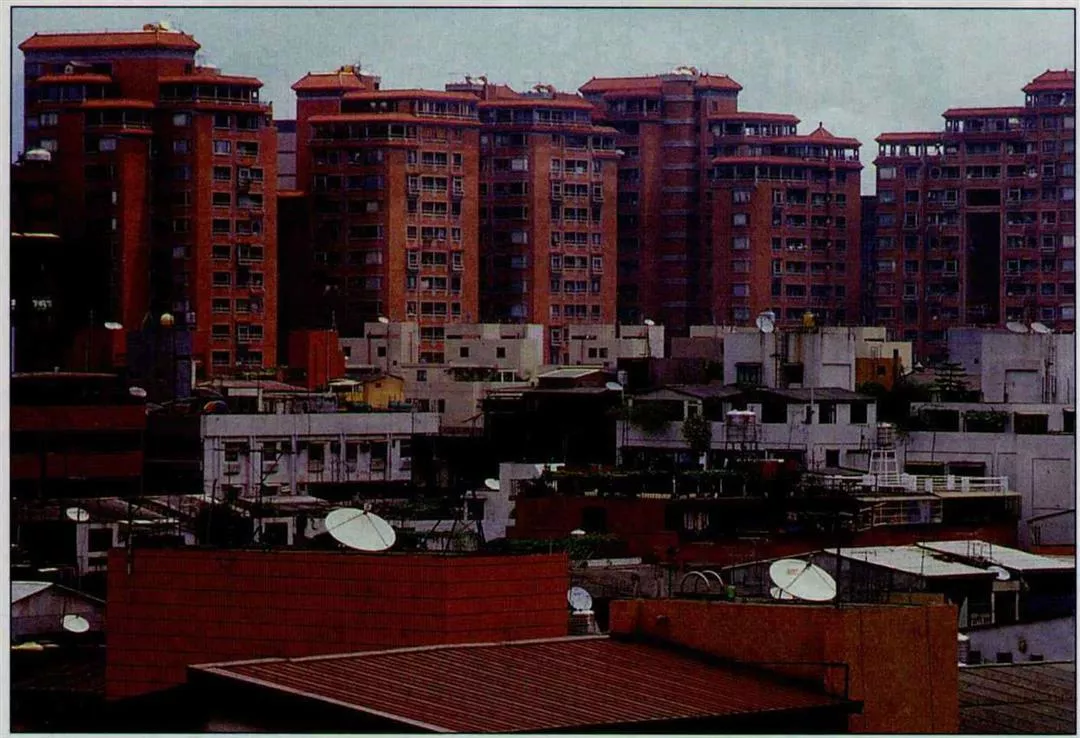

p.115

Whether or not foreign programs should be allowed into every home with absolutely no screening is a matter which is still being argued about all over the world.

p.116

The situation of satellite reception varies greatly between the countries of Asia: the R.O.C. permitted the installation of "small ear" receivers (above) four years ago; in Vietnam (facing page), where economic recovery has just begun, they are forbidden and the people have no means to install them.

p.118

Only when satellite television from abroad is both sensational and compatible with audience tastes can it penetrate the market.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)