Stuff of daily life

The NCKU Orchid R&D Center has used biotech to add value to the orchid industry by pushing orchids beyond their purely decorative uses, bringing orchid research out of the laboratory and creating products for people to use in their everyday lives.

“We’ve already found a few key genes, and we’ve applied for Taiwan and US patents so as to protect our intellectual property rights,” explains Chen. To date, they’ve obtained eight orchid gene patents and transferred two scent-related genetic techniques to biotech companies with the aim of creating commercially viable products.

The bellina moth orchid (Phalaenopsis bellina), which is native to Malaysia, does produce a scent. Chen notes that after it was introduced into Taiwan for crossbreeding, it won the top prize for its scent from the All Japan Orchid Society.

The NCKU Orchid R&D Center has transferred technology and provided guidance to Lan Hui Biotech, which is successfully extracting orchid embryonin for use in cosmetics. It has also taken bellina’s fragrance for a series of products, including essential oils, perfumes, soaps, and facial masks.

What’s more, the Orchid Biotechnology and Creativity Industry University Alliance is also trying to put orchid fragrance into food products, such as chocolate, cookies, tea, dalu gravy noodles and so forth.

From a global perspective, Taiwan’s orchids are indeed quite distinctive. “Different flowers have different associations, and in Taiwan moth orchids are associated with the word ‘happiness.’” Chen explains that Taiwan’s moth orchids’ strong suits are their long lives and lengthy flowering, as well as their hardiness in transport and the full round shapes of their blooms. The monkey face orchids (Dracula simia), bee orchids (Ophrys apifera), and vanda orchids grown abroad all lack round blooms, leaving Taiwan’s moth orchids with the singular distinction of being both large and round.

“So long as you believe, then happiness is right before your eyes.” How apt these words are—both for moth orchids and for the Taiwan orchid industry’s hopes for the future!

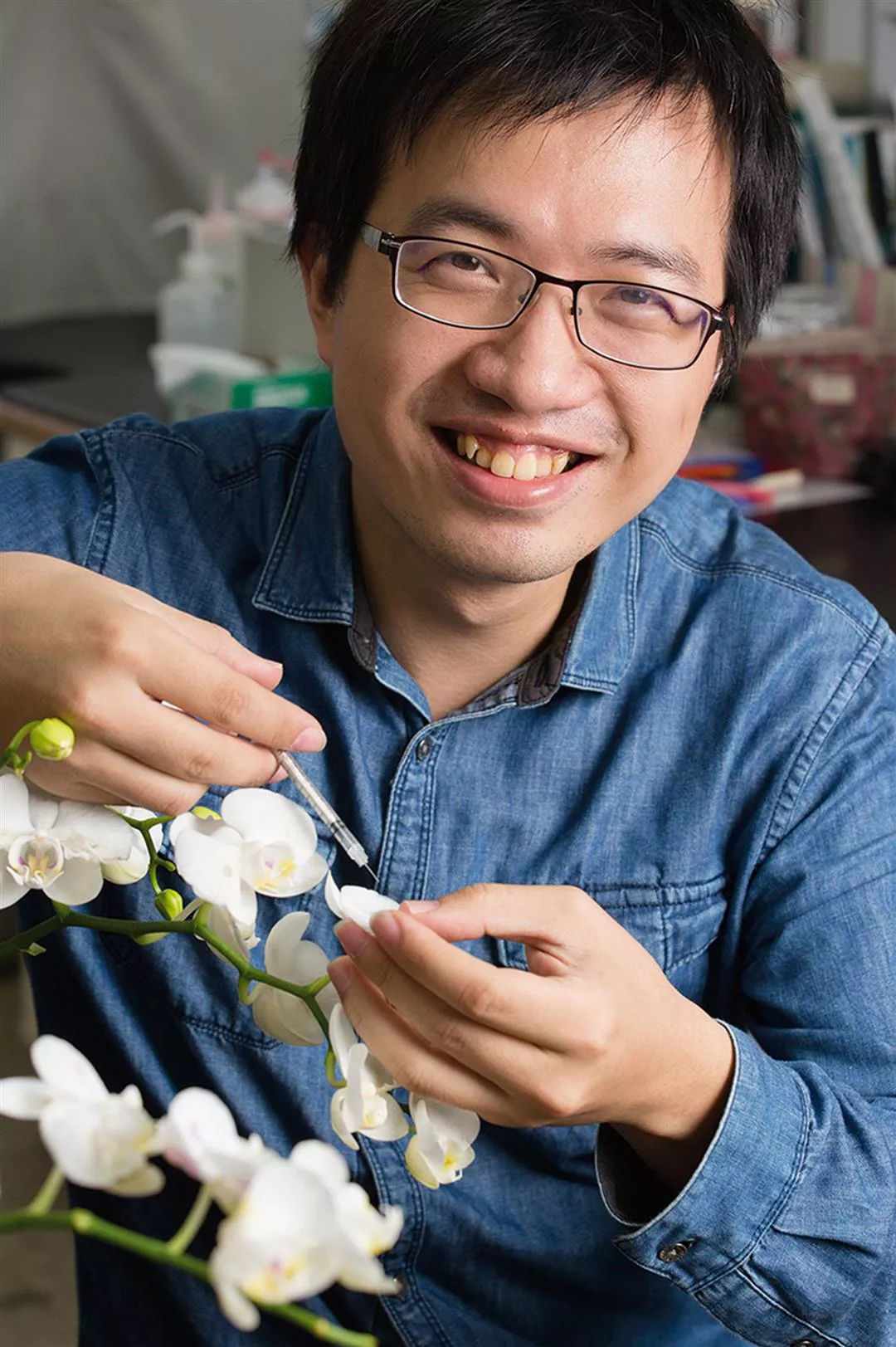

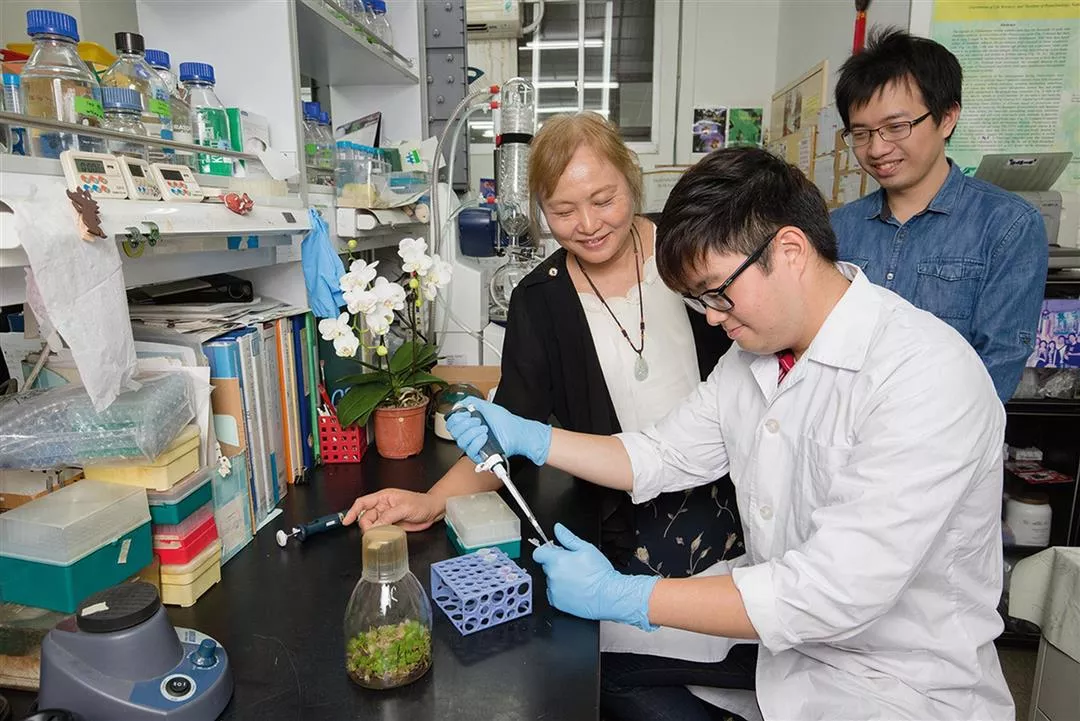

For a project overseen by Chen Hong-hwa, head of the orchid R&D center at NCKU, doctoral student Hsu Chia-chi injected an agrobacterium carrying the gene PeMYB2 into orchid petals. Four or five days later red patterns began to emerge.

For a project overseen by Chen Hong-hwa, head of the orchid R&D center at NCKU, doctoral student Hsu Chia-chi injected an agrobacterium carrying the gene PeMYB2 into orchid petals. Four or five days later red patterns began to emerge.

For a project overseen by Chen Hong-hwa, head of the orchid R&D center at NCKU, doctoral student Hsu Chia-chi injected an agrobacterium carrying the gene PeMYB2 into orchid petals. Four or five days later red patterns began to emerge.

Via the extraction of orchid embryonin, the fragrant aroma and blue pigment of the bellina orchid have been brought to a whole line of consumer cosmetic products.

Much-loved moth orchids are no longer found only with great difficulty in deep, dark forests. Apart from cultivated varieties being exported in large quantities, the flowers are also being put into many products that people use in their daily lives.