Reviving Chinese education:

The renewal of the economic role of the Chinese in Vietnam has meant that their status in the country is rapidly being recovered. One example of this is the unprecedented wave of enthusiasm for learning Chinese that is now sweeping Ho Chi Minh City. Practical considerations led the government to reopen the Chinese schools the year before last and there are now 56 licensed Chinese language teaching centers in the city, in addition to some 70 private culture centers providing language tuition.

"Classrooms fit for only 30 or 40 students often have to hold as many as 60 or 70 people," says school principal Wang Pei-chuan. There is no lack of children of Vietnamese officials among his students.

In addition to language classes, the restrictions on Chinese entering university were lifted in 1987. Entrance grades were raised, however, making it comparatively difficult for Chinese students to gain entrance.

The Chinese in Vietnam find sweet rewards in their hard work. Yet, as well as finally being able to take firm steps forward after having had their fill of war and chaos, they cannot avoid harboring a good deal of anxiety. The two generations of Chinese have their own particular concerns.

The worries of the older generation are not unusual: how to pass on the baton of the business? Chen Ai-tsai says that, for more than ten years, the youngsters have not had the experience of practical on-site training. "It is very hard for them to be like the Chinese were before, developing in all directions and laying down a big business network."

While the older people are concerned about the glory of former days, the younger are looking towards broader horizons and want to go overseas to study. "Go all out making money, and go abroad when the opportunity comes," sums up the feelings of the young Vietnamese-Chinese about their long-closed society and uncertain future.

After the young ones have left, will they ever return? "That depends on how Vietnam develops in the future!" is the answer.

Is it having been subjected to just too much distress in the past that stops the Chinese in Vietnam settling down and makes them go on drifting?

[Picture Caption]

p.120

Chinese-Vietnamese Vuu Khai Thanh and his wife have worked together to create Vietnam's largest private enterprise.

p.122

The vendors of Tan An make for a lively street scene.

p.122

Gifted at doing business, the overseas Chinese have become the vanguard of Vietam's economic recovery.

p.122

Signs in both Chinese and Vietnamese script soon let you know when you have arrived in Tan An.

p.123

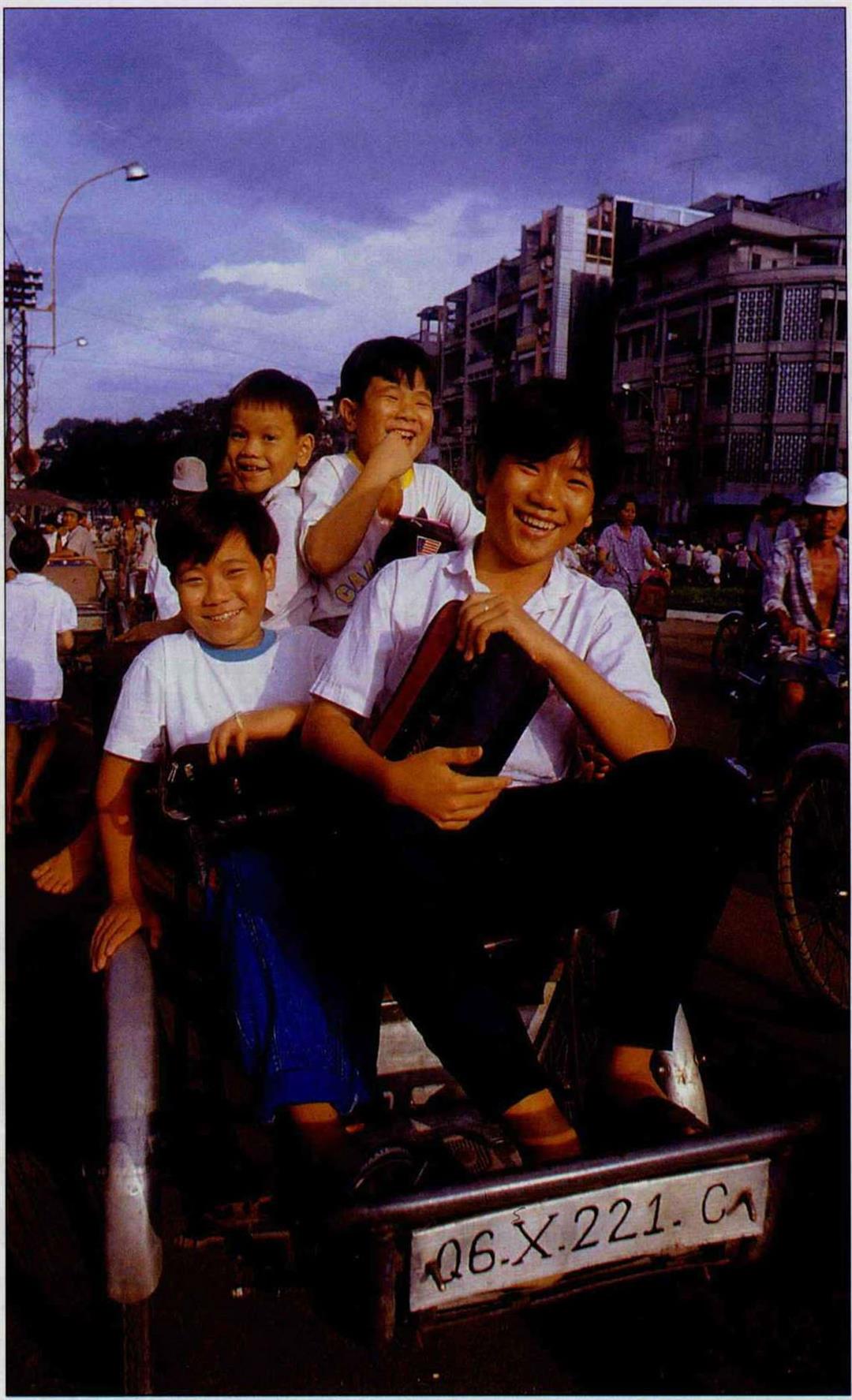

With the economy on the mend life is improving. The once rare sight of smiling faces can now be seen among the Chinese of Vietnam, who have passed through so much suffering.

p.124

With most of the Chinese in Vietnam having crossed the seas from the Chinese provinces of Canton and Fukien, the goddess Matsu who protects seafarers has become an important object of worship.

p.125

Chinese medicine is a centuries old trade for the overseas Chinese.

p.125

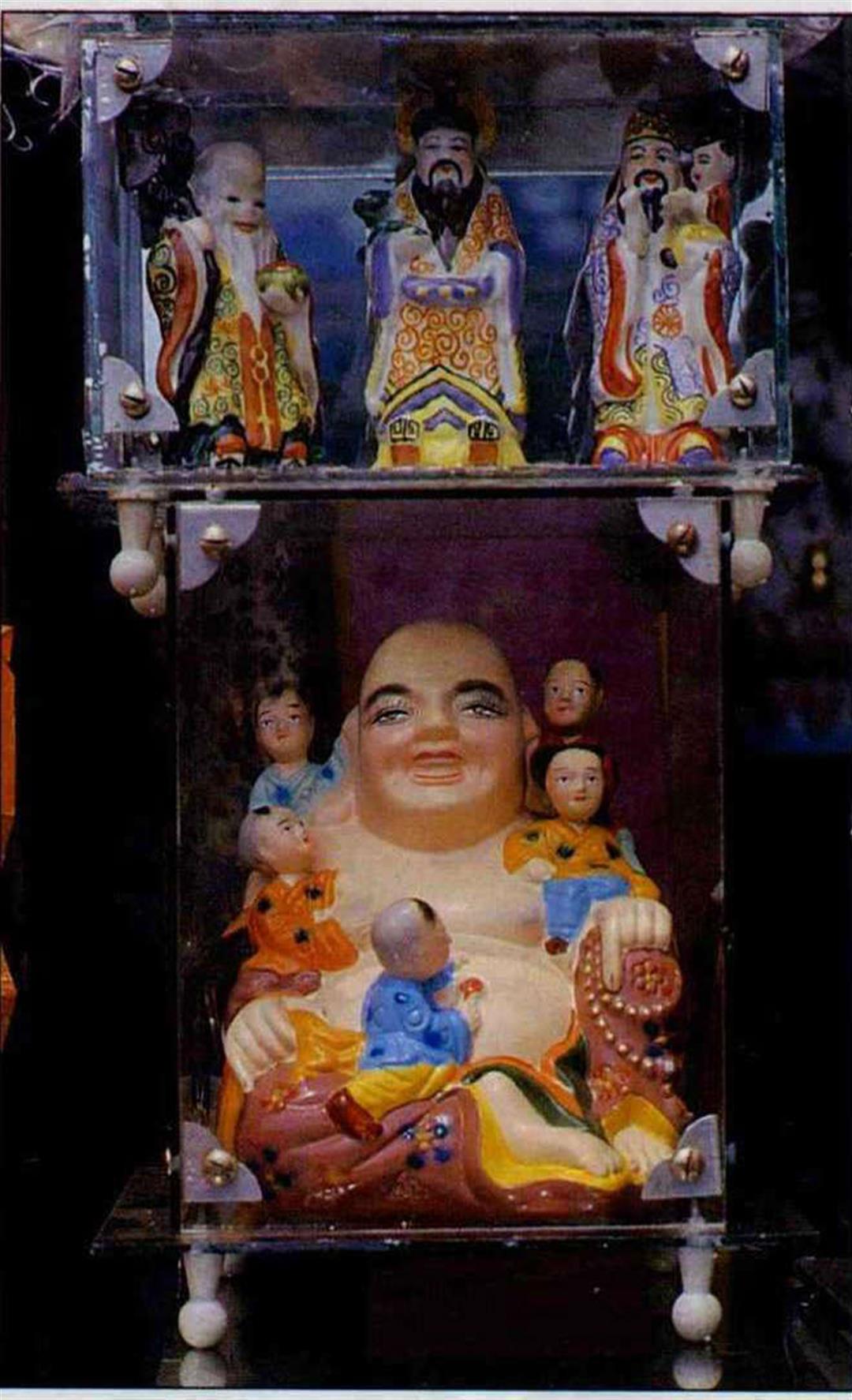

Having travelled so far from your home town, you can only ask the Buddha for protection, wealth and many descendants.

p.126

Chinese-language education has revived along with the economy, although members of the younger generation seem to have other ideas about the future.

Having travelled so far from your home town, you can only ask the Buddha for protection, wealth and many descendants.

Chinese-language education has revived along with the economy, although members of the younger generation seem to have other ideas about the future.