Grace Y. T. Tung has chosen to be a loner in her artistic and creative career. The art of Chinese calligraphy has a history of more than 3,000 years, and Tung absorbed the essence of it to create her own modern and individual style. As the fountain pen, ball point pen and pencil have almost completely replaced the brush in today's industrialized society, it has taken plenty of time, courage, and perseverance for her to gain her current place as a master of this dying but challenging art.

In late June this year, Grace Tung held an exhibition of her calligraphy at the Spring Gallery in Taipei which fully showed her majestic strength and fluid dignity. A casual observer might think that an artist with so much vigor must be a man. She instills life into her masterpieces by using themes from inscriptions on wooden tablets, door posts and screens. Observers may at first be taken by surprise at the innovations, before eventually accepting them.

Decades of dedicated practice have enabled Grace Tung to attain her present pre-eminence. She describes how she first took up calligraphy: "It all began when I was 8 or 9 years old. My father chose the calligraphic facsimile of Tan Yen-kai (a master specializing in Yen Chen-ching's style of calligraphy) for my brother and I to practice on. That summer, we both locked ourselves up in our study to practice 200 small characters and 100 big characters a day. We picked up the habit again the following winter vacation, and since then I have been captivated with calligraphy."

Through junior and senior high school, Grace Tung kept up her interest in calligraphy, and won numerous medals. Her decision to major in painting while studying at the department of fine arts at the National Normal University, prove helpful to her career in calligraphy. In this period, the style of master Yen Chen-ching, a famous calligrapher in the Tang dynasty, became rooted in her. But she continued to be inspired by the masterpieces of Chang Chien, Huang Shan-ku and Su Shih, and the facsimiles of tablets and stones of the Han, Wei and the Six Dynasties.

"Practice itself is not enough. It is of equal importance to peruse the works of great masters, and find out the style that fits in best with your temperament. After you have absorbed the best points of great masters, you must make a breakthrough and create your own style," she said. While she was studying in the United States, Grace Tung took her instruments along with her to practice and to teach foreign students her techniques.

Tung considers that using the brush pen helps to turn writing Chinese characters into art. The twists, turns, and boldness of ink strokes are reminiscent of Chinese wash drawing. Beauty exists in every style of Chinese calligraphy-from seal, clerical, running, cursive to standard.

Because modern Chinese homes are smaller than the spacious halls of ancient times, Grace Tung discarded traditional large-sized vertical and horizontal scrolls. Instead, she selected different styles of Chinese calligraphy and structure to match the subject matter. By combining traditional and modern styles, she has given each masterpiece a unique appearance and interest.

Most of the works on show at the exhibition are made up of simple and short inscriptions rather than long poetry or prose pieces. They are mainly laid out horizontally, mounted on boards and covered with glass. As decorations, they bring a touch of classical elegance to the modern living environment.

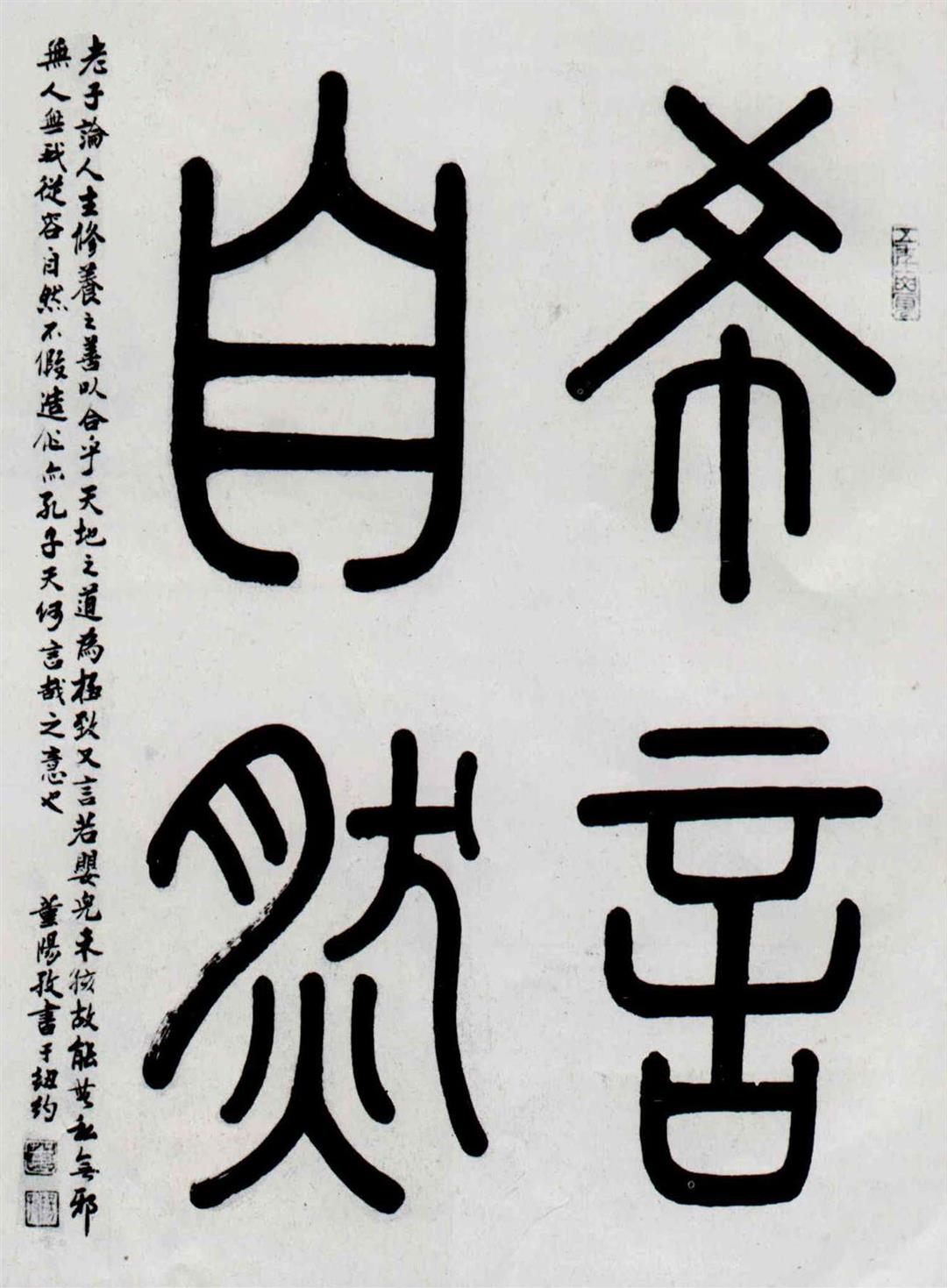

In the masterpiece pao yi (embracing one), Grace Tung writes down a passage in small characters as a foil to allow two large characters to stand out conspicuously, and to prevent the canvas from being empty and void of meaning. She recalled: "When I first decided to write these two characters, I tried all the possibilities and combinations, from standard, clerical, running to cursive styles without being satisfied. After I had written on and torn up 15 pieces of top quality paper, I became desperate with anguish. But I never gave up. Then one afternoon, the inspiration came to me like a miracle, and there it is. I was overjoyed."'

The masterpiece ta pei (great mercy), displays the artist's generous disposition and her sympathy for all mankind. Another masterpiece reads "to have is to have not; reality is nothing," which is full of philosophical meaning. Still other is lao ta yi chuan cho which means that people in old age become naive and revert to the primitive. The idea is conveyed vividly by the natural naivety of the characters themselves.

Grace Tung said that calligraphy which is not the result of much time and labor may turn out to be artificial, superficial or clumsy. Her penmanship certainly indicates her devotion to the art. It seems that the strength, weight, and vitality of each character written by the great calligrapher penetrates through the paper.

[Picture Caption]

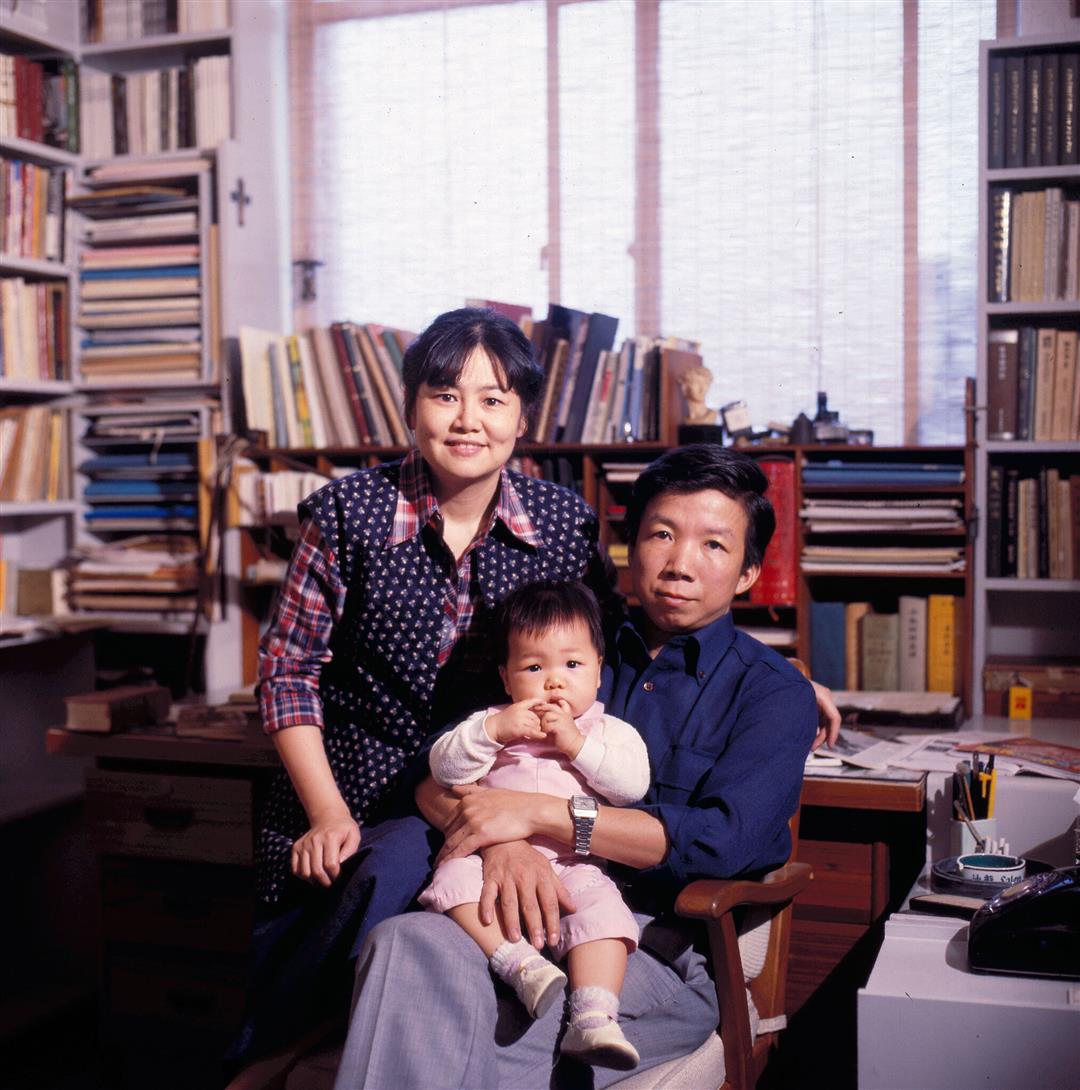

1. pao yi (embracing one), 2. Grace Tung at work. 3. Tung and her husband Ho Hui-shuo and their daughter.

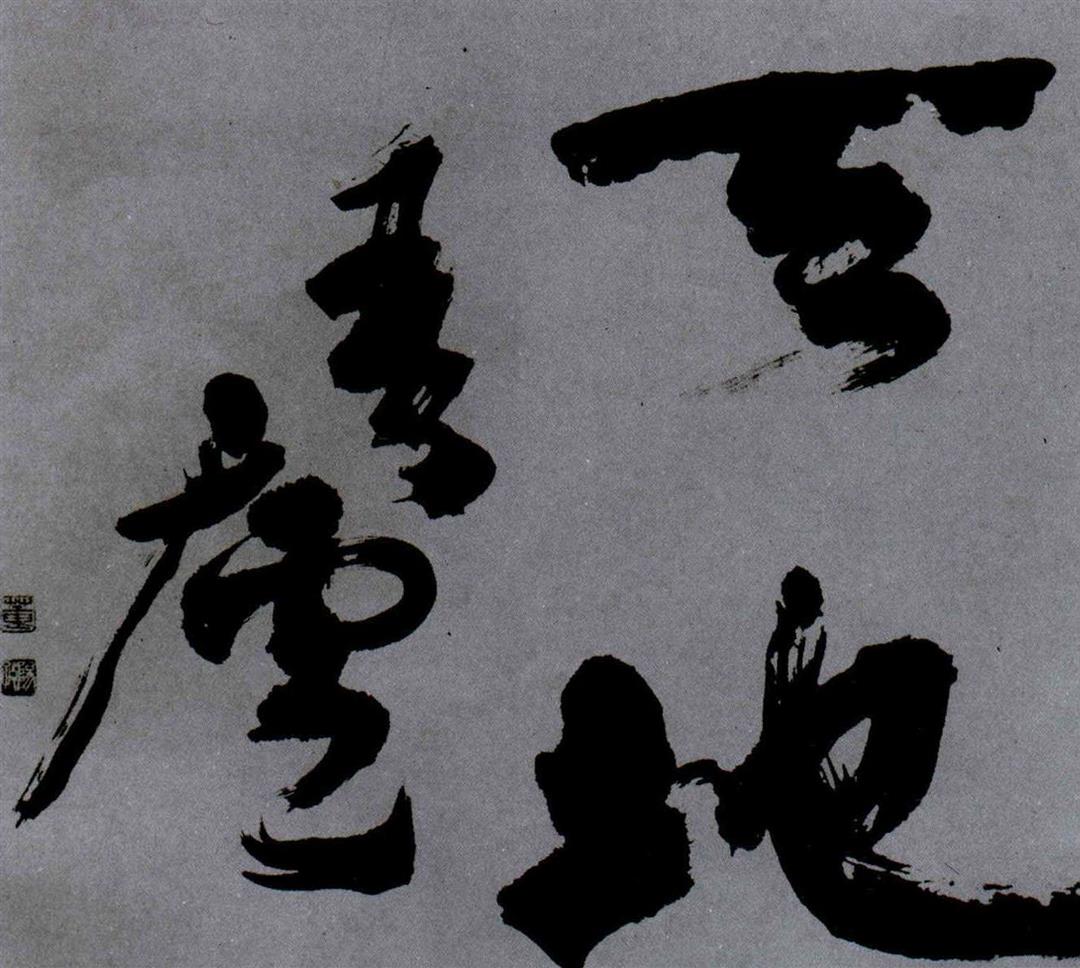

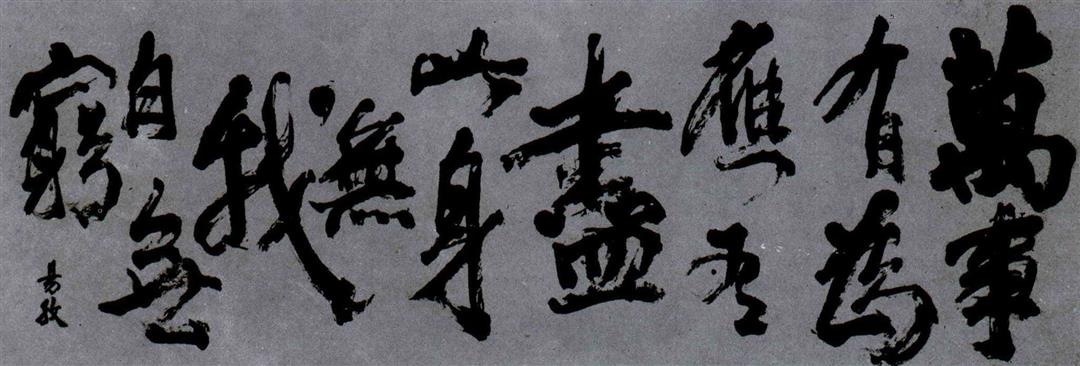

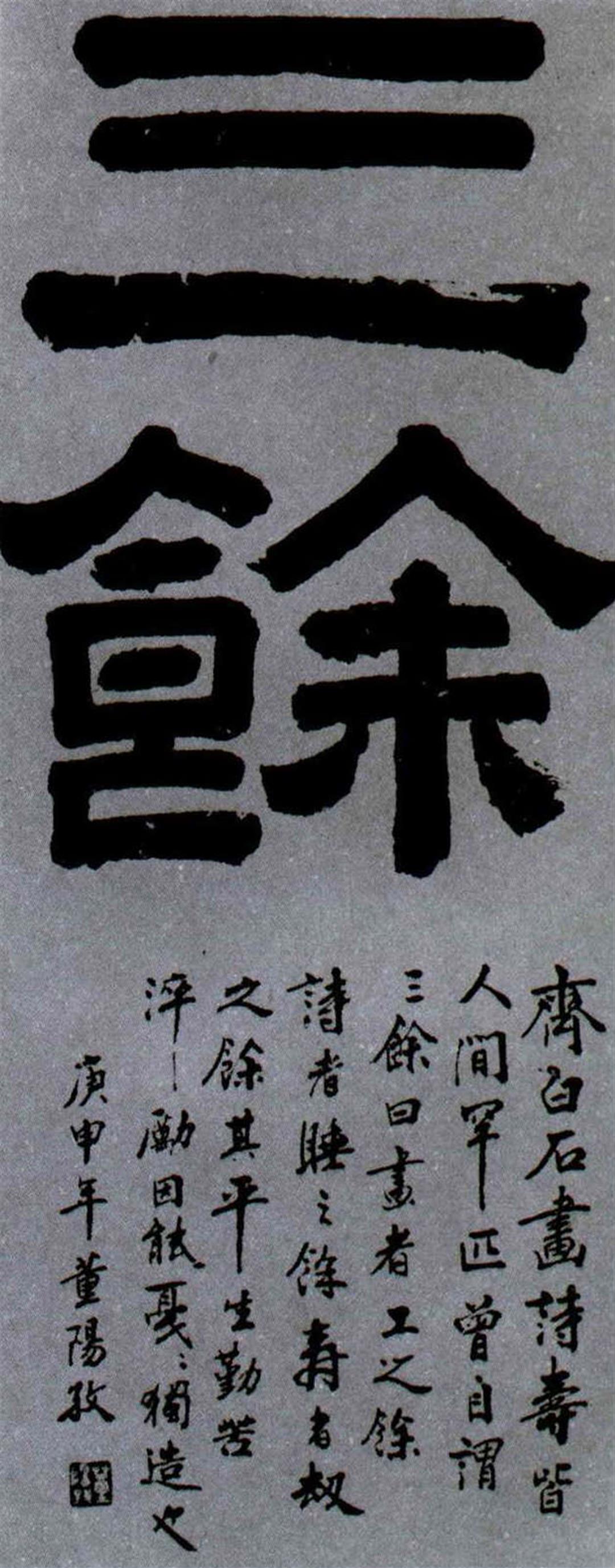

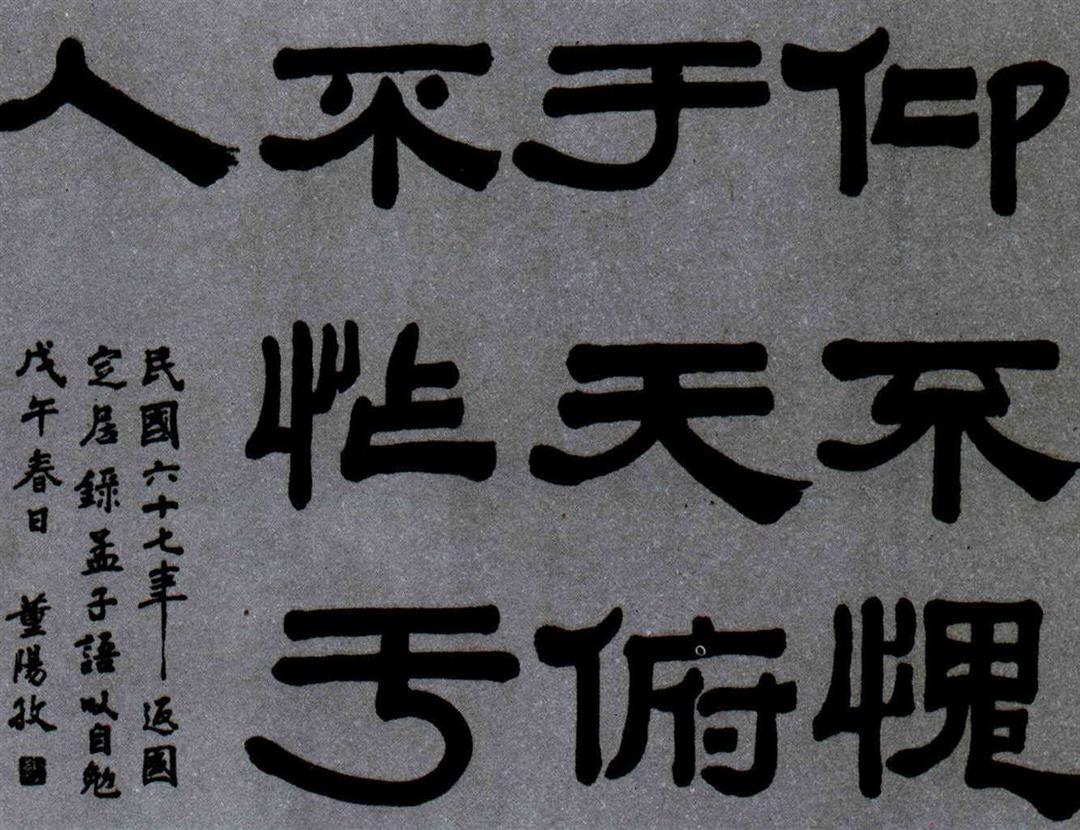

1. ta pei (great mercy). 2. hsi yen tzu jan (maintaining natural ways). 3. tien ti wu lu (heaven and earth are my home). 4. As everything has a purpose, it must also have a stop. Without greed, a person may attain immortality.

1. chi mu (look as far as possible). 2. san yu (three things remaining). 3. To feel no shame before heaven and earth.

Tung and her husband Ho Hui-shuo and their daughter.

hsi yen tzu jan (maintaining natural ways.

tien ti wu lu (heaven and earth are my home)

As everything has a purpose, it must also have a stop. Without greed, a person may attain immortality.

chi mu (look as far as possible.

san yu (three things remaining)

To feel no shame before heaven and earth.