Copying Jiu Cheng Gong

Born in 1954 in Hsinchu, Guan is master of Chinese calligraphy, ink painting and seal carving. At a 2010 solo exhibition at the National Museum of History, he was introduced as “potentially the greatest painter and calligrapher of his age.” His landscape paintings employ delicate and graceful strokes in elegant colors. A critic has commented that his works are “simple, unadorned and generous..., sometimes employing real scenes, sometimes scenes created within his own imagination. He captures not only the magnificence of the landscape as a whole, but also allows us to glimpse the elegance and purity of its many tiny parts.”

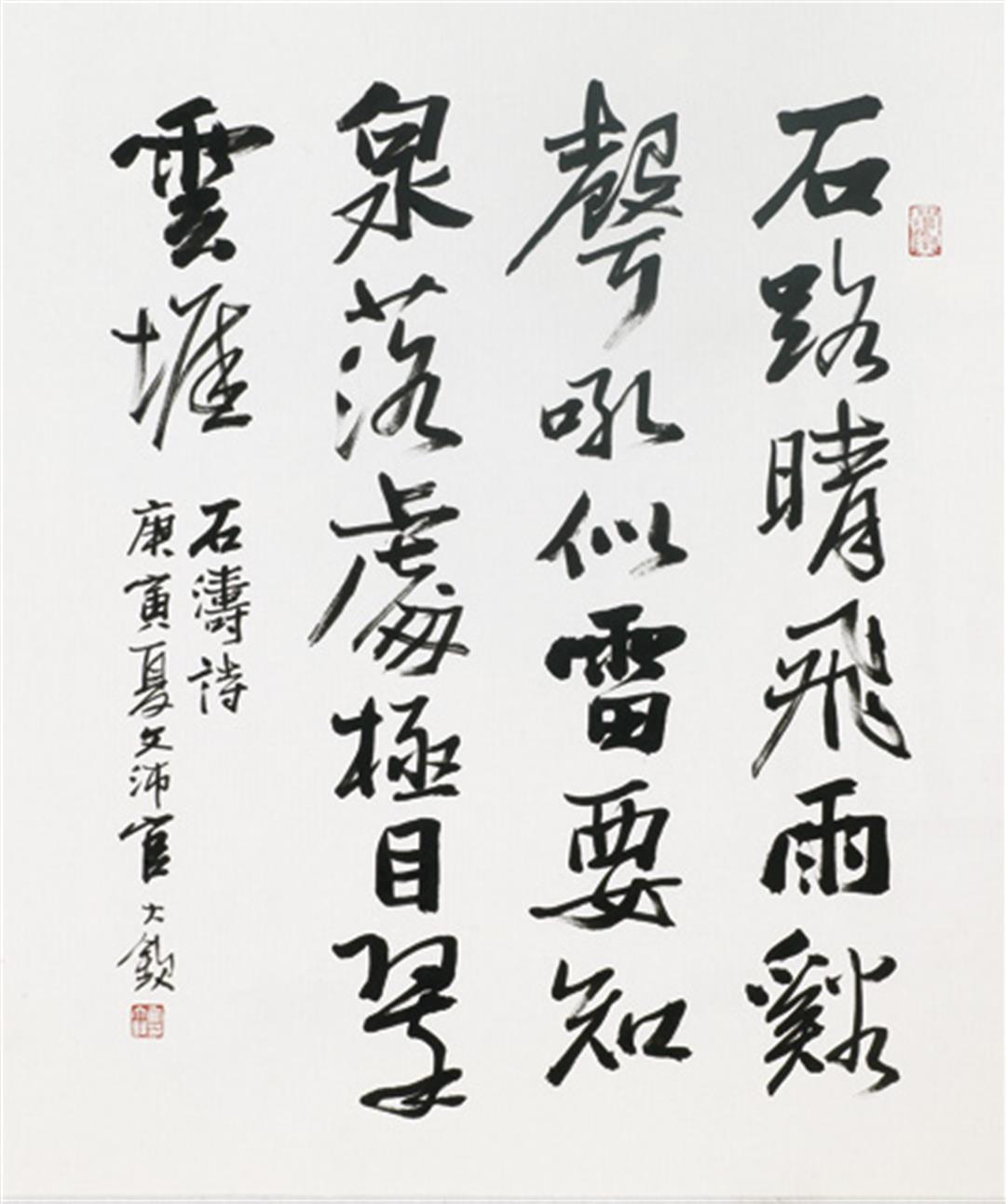

Guan’s calligraphy is well known for his skill in clerical and semi-regular script styles, and his incorporation of the exemplary models of the Han and Wei Dynasties into his own style that bursts with dynamics and rhythm.

Guan’s work is deeply influenced by his teacher Chiang Chao-shen, a devotee of the model Jiu Cheng Gong, which is the foundation of studying brush writing for Chiang’s students.

Jiu Cheng Gong Li Quan Ming, to give it its full name, is a creation of renowned official Ouyang Xun from the Tang Dynasty, known as a sophisticated and quite vigorous work. Despite its difficulty for learners, it has become the most popular model to copy.

“It’s inevitable that learners become frustrated because it’s so difficult to emulate well,” explains Guan. Since the model contains more than 1000 characters, copying 28 characters a week it would take a full year to complete the whole work. One has to copy all the characters three times over to begin to grasp a little of the quintessence of Ouyang’s work.

Guan’s work Shi Tao Poem displays his technique of pure and unadorned brush strokes, the result of several decades of hard work.