This June at the 30th annual Asian-Pacific Film Festival, the best director honors went to the R.O.C's Hou Hsiaohsien and his "A Summer At Grandpa's". The decision surprised none who know this talented director and his work. Besides two Golden Horse Prizes won here, Hou has also won praise at film festivals in Cannes, Edinburgh, Montreux and Tokyo, to name a few. French film critic Pierre Rissient called him the most promising director in Taiwan. His friends joke that he is becoming a professional film festival entrant.

Born in Mei County in Kwangtung, Hou Hsiao-hsien grew up in the Taiwan countryside, which provided him with a mother-lode of experience that he taps frequently in. his films. Wearing shorts every day, catching shrimp, embarrassedly going out on a first date, and staging mock sword battles in the street all combine to help Hou express his vision, served on a rich backdrop of deep blue skies, green rice paddies, and chirping cicadas. His skill and vivid presentation frequently leave audiences in Taiwan recalling their own childhood.

Hou Hsiao-hsien's artistic philosophy emphasizes the importance of real experience. "Actually, technique is extremely unreliable. Many people use it but you can really depend only on thought and content." He notes that postwar greats Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini usually "drowned" their audiences in content, leaving viewers with little energy to focus on style and technique. When not making movies, Hou spends his time reading and watching videotapes of other films. He says, "Life never stops changing, and one must keep being nourished by it and digesting it before one can create anything."

Hou spent one winter in the P'eng-hu Islands. One day he strolled into a store in Fengkuei and found a group of youths aimlessly playing pool, joking and cursing as they killed time. He immediately reached for his notebook and sketched the characters, the general scene, and his own reaction. "They looked like they'd dropped out of school and just floated through life. Looking at them made me think how accidents can happen anytime when one is young and how youth is full of unpredictable sorrow and tragedy." Thus was the start of "The Boys From Fengkuei".

As the above story indicates, Hou prefers to use direct experiences as his subject matter. His favorite saying is, "Learning comes from outside the school, and movies come from outside the studio." He favors working from specific characters and letting them and their stories develop naturally, rather than selecting a theme and then finding suitable material to flesh it out.

"I've actually always been pretty ignorant about movies," says Hou Hsiao-hsien. When asked why he makes films, Hou responds, "For fun!", usually leaving the questioner disappointed. Nowadays he adds to his answer by quoting a Japanese director, saying, "I love life and living people." Add this to his curiosity and perceptiveness, and one would probably be close to the answer.

As a child his behavior and interests were far from those of a model youth. He spent much of his time prowling about other people's business, exploring alleys and discussing neighbors. He often patronized the outdoor opera near his home, and an early dislike of school sent him to reading wuhsia novels (Chinese kungfu adventure stories) and filling his imagination with their heroes.

Movies were another pastime. If he had money, he would buy a ticket. Without money, the back door provided another alternative. Too young to analyze, he eagerly drank in the sights and sounds of the films, in a purely sensual way, which later formed the foundation of his cinematic inspiration.

Failing the college entrance exam, Hou went into the army. On his days off, he usually would head for the movie theatre, where, bleary-eyed, he would sit through four shows. Hou recalls during this time seeing a British film, "Crossroads", which prompted him to consider movies as a career.

After discharge from the service, he headed for film school. Upon graduation his sights were set on acting, but his baby face and average build failed to arouse much interest in the film industry, crushing his original hopes. He thought at the time, "Why can't I go hide and be a director?"

Luck began to turn his way. A teacher helped him to get a job with Li Hsing and from there he was promoted to assistant director and editor. Old colleagues recall him as being generally taciturn but energetic and responsible. Says Li, "I liked his editing work a lot. He had extensive practical experience and was good at organizing material into scenes. A very creative and thoughtful man." In 1979 he and cinematographer Ch'eng K'un-hou collaborated on their first movie in what was to be a series of well-received films. Four years ago Hou and author Chu T'ien-wen adapted the latter's story, "Growing Up", for the screen, making a film that grossed over NT$30 million in Taiwan.

"The Boys From Fengkuei" came later, at an important time for Hou Hsiaohsien. An earlier film, "The Sandwich Man", had won critical acclaim, and Hou began to wonder if directing movies might be more than just a way to make a living and pay the bills. This and the realization, coming from conversations with film directors returning from overseas, that his approach coincided with foreign cinematic theories gave him a heightened sense of responsibility and left him confused under the pressure of conflicting emotions. Reading a moving autobiography by author Shen Ts'ung-wen helped him cope with the difficult situation that fate and his talent had plunged him into, and Hou soon began work on "The Boys From Fengkuei".

The film in some respects marked a breakthrough for Hou. The story involved a group of youths from the country making their way in the big city, leading frustrated, aimless lives as they wait to be called into the military. Critics have praised its verve and realism, noting that while Hou is quite objective, his portrayal of the youths is far from noncommital. He gives them their own style of heroism and morality, and refuses to attribute their criminal tendencies to a rigid school system or strict parents, finding instead also a natural youthful rebelliousness. And while his characters are quick to pick a fight, the sight of a wounded foe will set them running. They aren't even able to successfully kill a chicken.

Hou's movies bear their own distinctive stamp. He often improvises on the set, using technicians as actors or deciding that a local onlooker would be appropriate for a certain scene. Explains Hou, "Actors aren't familiar with the location, and so their walk and movements aren't quite right sometimes. Locals fit in with the environment and look more natural." He frequently uses actors' suggestions, creating a strong sense of participation and freedom on the set, says actress Yang Li-yin. Hou likes to use mid-range and long range shots believing they better capture the subject in his or her own environment. Sounds and voices from people offscreen are also employed by Hou with considerable skill.

Humor is yet another characteristic. In "The Time To Live And The Time To Die", an old grandmother has packed up her belongings, since she wants to be ready in a pinch to return to her ancestral home on the mainland. One day she and her grandson set off, and not surprisingly are unable to find the right road. Instead they land in a guava orchard, where the grandmother suddenly switches her attention from the mainland to teaching her grandson her own special technique for juggling guava.

"The Time To Live And The Time To Die" is Hou's most ambitious work to date. Incorporating parts of his own biography and discussing the complexities of Taiwan's post-1949 society, some have criticized Hou as having risen too far too fast. Others admire his craftsmanship and his unwillingness to compromise, feeling that he will make significant contributions to Chinese cinema. As a child, Hou's grandmother used to pamper him, after a fortune teller told her grandson would become a high official. Though his career took an unscheduled turn, no doubt Hou's steadfastness, concern for society, and intelligence would still make his grandmother proud.

(Mark Halperin)

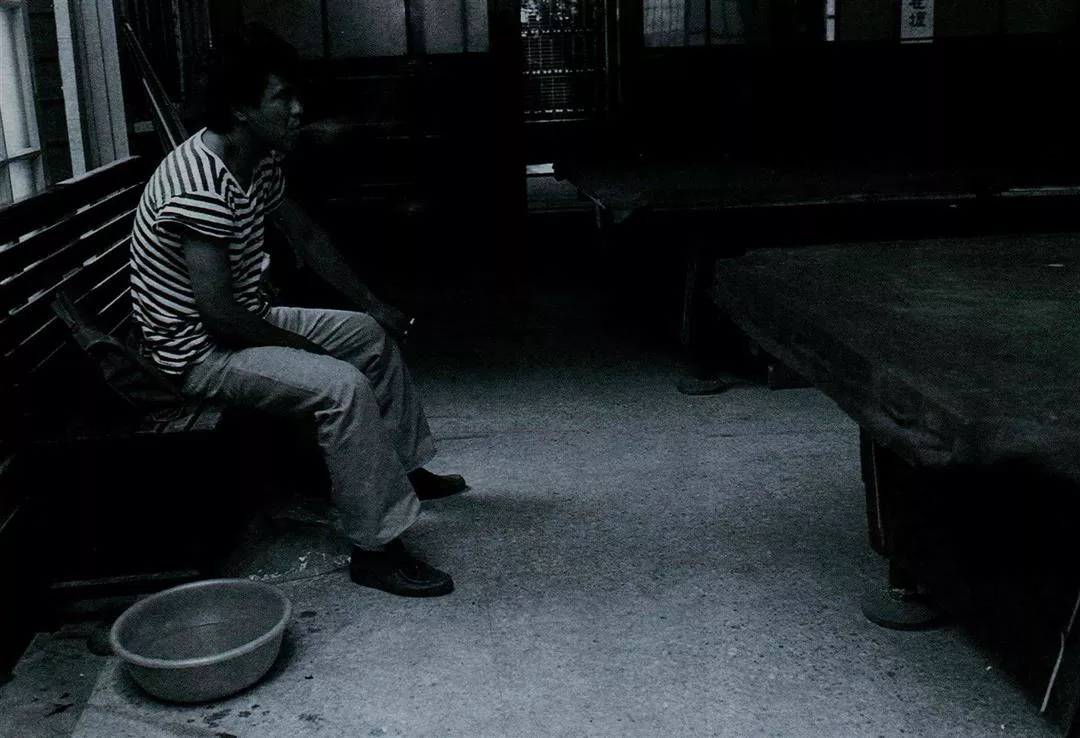

[Picture Caption]

Childhood occupies an important place in the films of Hou Hsiao-hsien.

Hou is also a good actor, with a store of facial expressions.

Hou pauses for a break between scenes and searches for new inspiration.

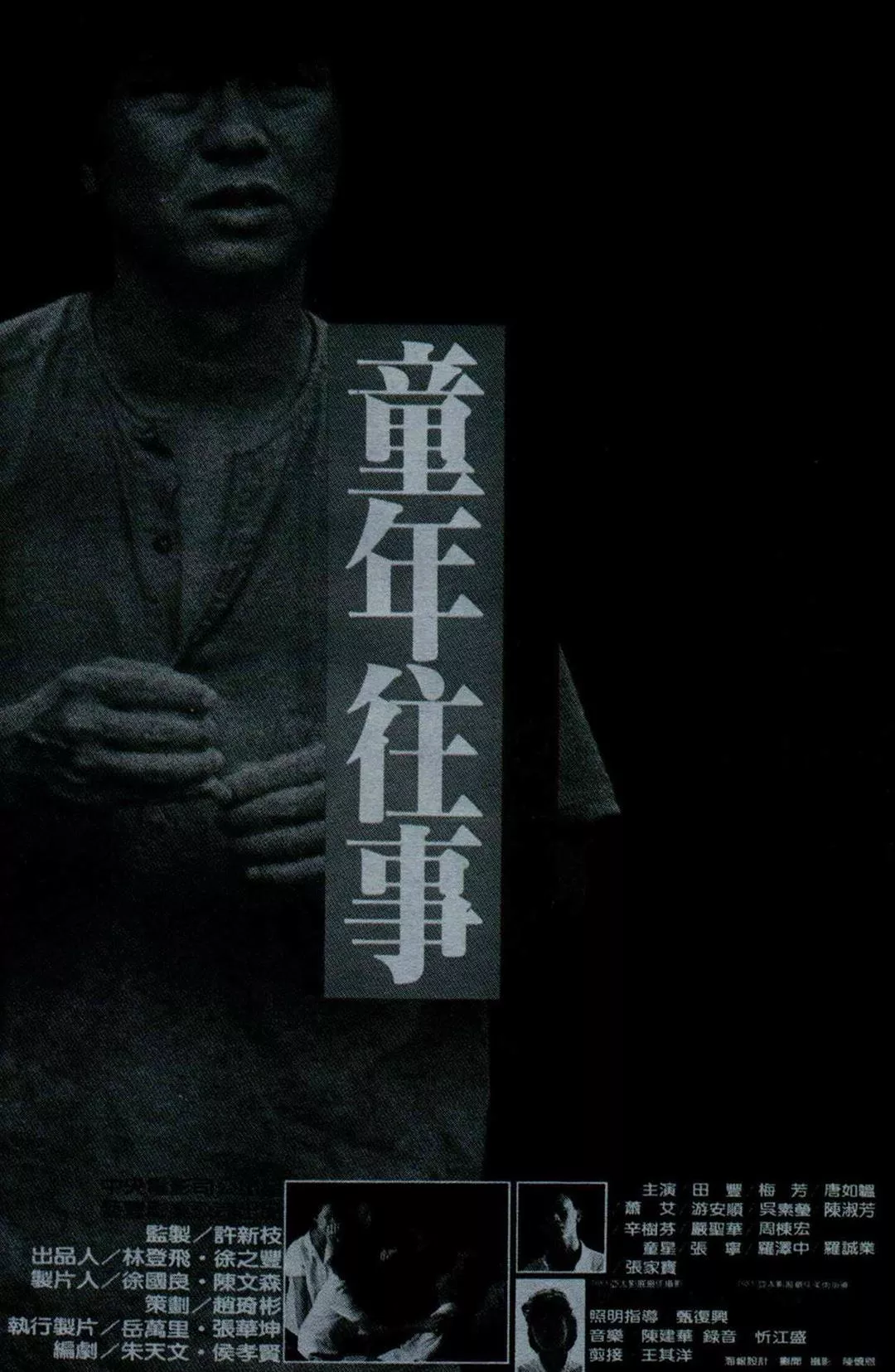

"The Time To Live And The Time To Die" is the first autobiographical movie in Taiwan.

Hou shows a young actor how to spin a top.

Tired after a day of shooting, Hou heads for a bowl of fruit ices.

Deep in thought, what will be the subject of his next film?

Hou is also a good actor, with a store of facial expressions.

Hou pauses for a break between scenes and searches for new inspiration.

"The Time To Live And The Time To Die" is the first autobiographical movie in Taiwan.

Hou shows a young actor how to spin a top.

Tired after a day of shooting, Hou heads for a bowl of fruit ices.