Looking at Chao Shu-hsia's publicity photograph is a surprisingly captivating experience. Her 1950s-style hair and eyebrows sit over a pretty face and in her subtle smile there is a hidden melancholy. In her marriage she is a wife and mother with four mouths to feed and a dog but somehow she has still managed to plough through masses of Chinese and foreign historical evidence to write her prize-winning novel.

As the twenty-minute journey from Zurich to the industrial town of Winterthur passes through tranquil Swiss scenery, you cannot help thinking of Harry Lime's parting words in The Third Man: "In Italy for 30 years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, bloodshed--they produced Michelangelo. Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love, five hundred years of democracy and peace and what did they produce--the cuckoo clock!"

Sardonic words, indeed. But if you ask a Chinese person who has been through war and strife, they would most likely prefer to diligently produce cute clocks and take their spare time and money to go abroad and enjoy the fruits of their labor.

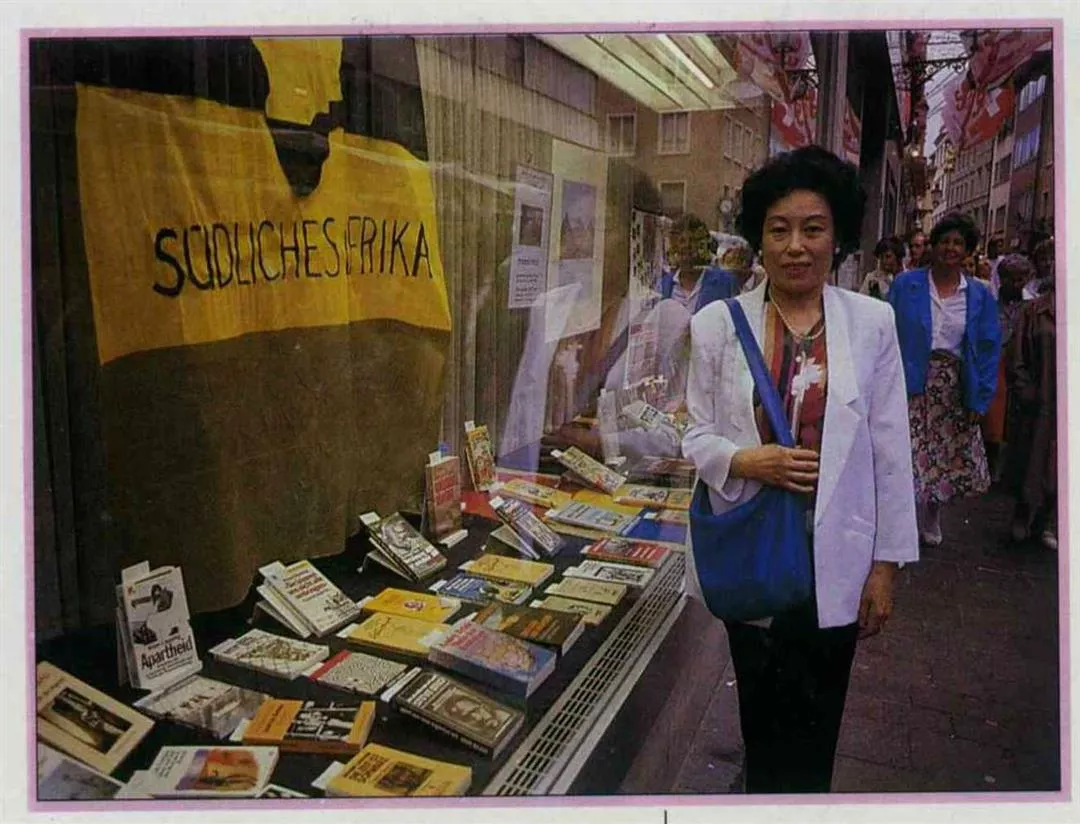

Susie Chen appeared at the station still recognizable from her photograph. The town happened to be holding its festival with the streets full of colored pennants and stalls. This kind of bustle is an unusual occurrence in Switzerland and Chao Shu-hsia was obviously excited. She suggested we talk as we strolled the streets.

Introducing the town, we passed the town hall, where she used to speak as representative for newly naturalized citizens, and a bookshop with her novels on display. She is now an upright Swiss citizen, but sitting in a coffee shop looking at some boisterous young people gathering to drink, she still raised her eyebrows disapprovingly of "Those young Swiss!"

This feeling of being an outsider does not in fact arise only when she is looking at young Swiss people but also comes to the surface time and again in her works. On seeing some overseas Taiwanese students in Munich, she could only think, "These representatives of the new generation are much more fortunate than my own generation. They have grown up in a safe, happy and wealthy environment, have not been through war and suffering and have not seen great bloodshed and upheaval."

Chao Shu-hsia was born in the 1920s and lived in a large house in Peking as a child. Being very strictly brought up, she describes how she used to lie at the front gate enviously peering through the crack at her friends carrying their satchels to school and even taking out money to buy food. After a tearful scene her parents eventually promised to allow her to attend school accompanied by a servant.

Unfortunately, just as she was on the verge of becoming a student, her "plump white" good-tempered teacher nervously announced, aggression: the Opium War, the eight armies against the Boxers . . . now the Japanese have "Children, we are finally resisting! . . . Of old we Chinese have suffered from foreign come to bully us. However they attack us, we will retaliate in the same way. Do not accept the aggression of the little devils!"

The children were very excited. Nobody thought, "The Japanese have not been expelled, we have been expelled ourselves." Chao Shu-hsia remembers how her family hurriedly packed a few belongings and boarded a refugee train in the early morning and began their long flight from the invaders. From then on, she passed her childhood as a witness to bombing and bloodshed.

In a roundabout way she eventually came to Taiwan and attended high school. Still, she was a despondent child. With many sisters, her parents naturally had no way to give them all their full attention. Her interests inclined towards the arts but her father was a very practical person and would not support this, so she became depressed. On graduating from high school she became a radio broadcaster, editor and bank clerk, finally saving up enough money to go to Paris and begin her study of the arts.

After two years in Paris, Chao Shu-hsia fell in love and married. She then followed her husband to Switzerland and studied applied arts, obtaining a designer's license. She now had a famous scientist for a husband, some lovely children and became a naturalized Swiss. Yet although she could now enjoy the peace of Switzerland she still bore the heavy burden of her past. The part of her that had been through the shock of war could not go away and she became an obvious outsider.

In 1972 she took her son and daughter to visit relatives in Taiwan. But as soon as they got off the plane her two small companions started to feel uncomfortable in the new environment. When she went out herself, she could not find her way home and the beef and noodles she had been dreaming of for so long did not taste so good. "It was as if everything had changed," she recalls. "Of course, my own youth had gone and it hurt a little."

When she returned to Switzerland, she began to get up early so as to have time to write as well as doing housework. From describing the anxiety of her youth she began her first novel. Luo Ti. She then wrote about her life as an overseas student and overseas Chinese circles and Women ti Ke (Our Song) was published in the Central Daily News and warmly received, finally releasing her pent-up feelings of loneliness.

In 1982, she again summed up her courage and visited relatives in mainland China, "Crying as I went and crying as I returned." In three weeks traveling she only wanted to return home--to Switzerland. "If the purpose of traveling thousands of miles is to find your roots, this was just in vain," she says. "Finally, I saw clearly, my roots had already been completely severed and pulled up." When she boarded the Swissair plane at Peking airport, she surprised herself when she let out a sigh of relief--something she did not dare to believe of herself.

Has she put down deep roots in Switzerland then? Not necessarily. When it comes to Swiss national day, every home hangs up flags and lights fireworks. "If we also hang up the Swiss flag and lanterns, are we celebrating? It is very unnatural so we do not do it. Yet to completely ignore it is also wrong. . ." she ponders. However, when the next-door neighbors get their flag out, fill their garden with pennants and lanterns and invite friends in to chat and drink, her pain begins to surface again: although the man in that family only works as a foreman in a factory, they can still have this kind of trouble-free life. How heaven smiles on the people of this peaceful and uneventful land!

Not only is she like this in Switzerland but when she travels to different places in Europe to lecture, attend conferences or tour, she is always aroused by her circumstances and everywhere can upset her. Strolling through the rain at Cambridge and looking at the great willows by the river reminds her of her distant home: "The people in that great land should also have the conditions to be the most fortunate people in the world, but they sweat blood and tears . . . and life for their children is still so unfortunate, always suffering. . . . "

Naturally, Chao Shu-hsia's homesickness frequently comes out in her writing, which has made her a famous patriot. "Some people say I can never break out of this patriotic frame," she remarks. Yet hers is not the misguided patriotism of the Boxers, she insists, "I love the nation that gave me succor, what is wrong with that? As for my people, I have some real feeling and sincere concern. I like to write so as to stir up the patriotism of the people. This is not just loyalty to my own heart, it is also what an intellectual should do."

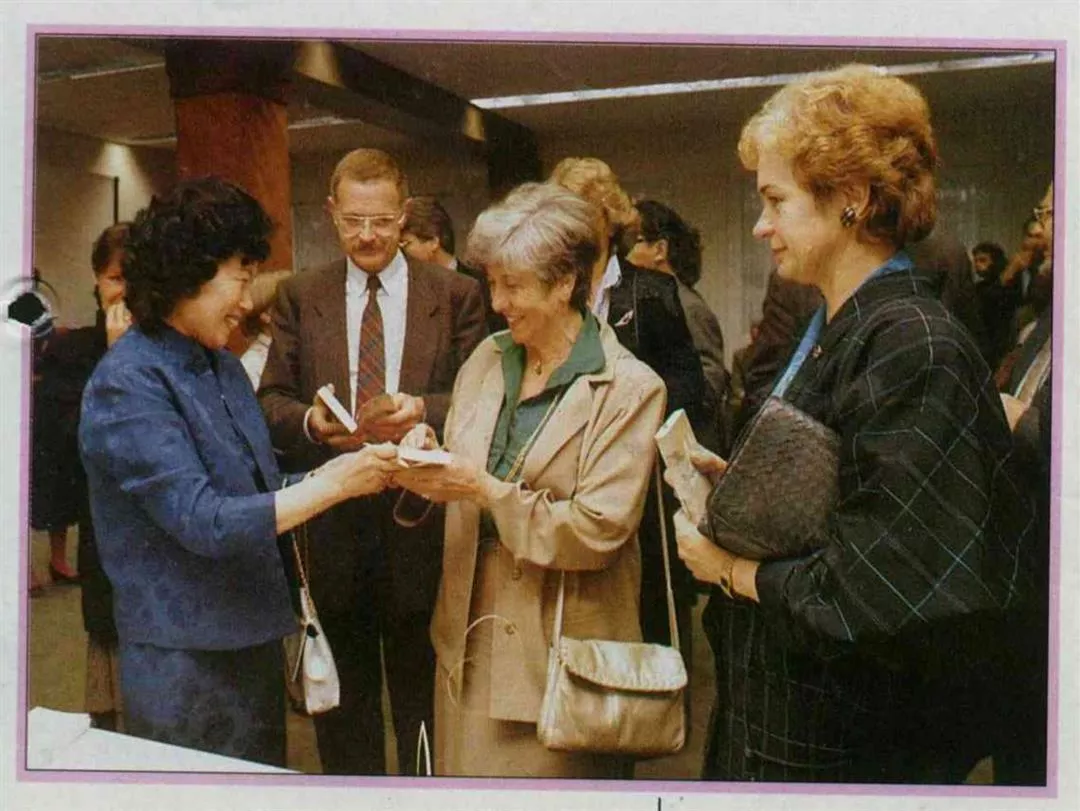

In recent years, her patriotism has advanced into European society. Beginning in 1986, her works were translated and published in German, with a happy outcome. She also entered writers associations and other organizations, and is invited to take part in literary meetings, lectures, book launches, and has opportunities to discuss issues with European readers, such as the differences between Eastern and Western culture. She tells them, "I like to describe overseas Chinese and the countries they live in, to improve understanding between new immigrants and the native people, and build up even deeper feelings."

Breaking onto the European cultural stage is not easy. Chao Shu-hsia had to struggle hard by herself and her books came out one by one. The most recent, Sai Chin Hua, is dealing with an issue involving both China and Germany and will therefore be read with even more interest. It is to be translated into both English and German.

From the anxious youth of Lou Ti, to the love of home and country of the overseas student of Women ti Ke, the broken dream of returning home in Fei-ts'ui Chieh-chih, up to the coming together of China and the West in the period of the Boxer Rebellion, Chao Shu-hsia has written down the heavy burden of her own heart while also speaking out about the sorrow and suffering of the overseas Chinese.

Recently she has also been busy organizing the European branch of the World Chinese-Language Writers Association, to help authors in their lonely struggle. She says that, when the organization is in place, everybody can come together like brothers and sisters, to discuss and exchange experiences and, of course, alleviate their homesickness.

[Picture Caption]

Chao Shu-hsia's captivating official publicity photograph. (photo courtesy of Chao Shu-hsia)

The town hall at Winterthur spoke as representative for newly naturalized citizens.

The novels of Susie Chen (Chao Shu-hsia) on display in a Winterthur book shop.

Giving her autograph to some admiring readers.

(Photo Courtesy of Chao Shu-hsia)

The town hall at Winterthur spoke as representative for newly naturalized citizens.

The novels of Susie Chen (Chao Shu-hsia) on display in a Winterthur book shop.

Giving her autograph to some admiring readers.(Photo Courtesy of Chao Shu-hsia)