"Is Ms. Ch'en home?"

"I'm Ms. Ch'en. What can I do for you?" said a very pregnant Ms. Ch'en as she went to answer the door, her brows knitted in puzzlement.

"Oh, I see. I'm Ch'iu Mei-wen, a nurse from the Public Health Department. I won't trouble you for long. May I come in?" Fearing possible rejection, Ch'iu immediately breaks into a tender smile.

"Well, I still have to do the laundry, feed the kids..."

"Taking care of kids sure isn't easy. I've heard you have five. That must be quite a burden. I'd like to talk with you and maybe help you out a bit."

"What, contraception?" Ms. Ch'en voice climbs to a high feminine pitch. "Hm. . . Ms. Ch'iu, that won't do. Other nurses before told me not to have more children, but I've only five daughters, not one son. My husband was the only boy in his family, and my parents-in-law want me very much to have a boy to carry on the family name. No way can I use contraceptives. I think you'd better go. If my mother-in-law came in, she might get upset."

Having met with a polite no, Ch'iu Mei-wen can only try to make a graceful exit. "Well, I'll just leave my card and these materials. And if the need should arise, please get in touch with me."

Newly industrializing countries usually show slowing population growth rates, as the costs of rearing children rise and the bias for boys begins to weaken. In Taiwan, however, the traditional preference for sons over daughters still remains. The average woman in Taiwan, according to statistics, wants 2.8 children, with 1.6 being male and 1.2 being female. Yet that same average woman often ends up with 3.5 children, usually because the early arrivals weren't sons but daughters. Such attitudes have pushed Taiwan's population past the 19 million mark and given the country a population density of 528 people per square kilometer, second in the world only to Bangladesh. Some people then naturally wonder, "If parents could choose the sex of their baby, couldn't this problem be solved?'

This question actually has been receiving attention for a long time. Aristotle believed that intercourse in northerly winds would produce male offspring. Hippocrates claimed that sperm from the right testicle would yield sons, and French aristocrats in the 18th century believed him to the point of cutting off their left one. Some cultures held that burying the placenta from a previous birth under a walnut tree would do the trick. One Bengali myth said that intercourse during menstruation on even-numbered days would produce boys, with love-making on odd-numbered days resulting in girls.

Such nostrums are not foreign to China. The oldest technique involves a chart, which translates roughly as "The Precious Palace Sex Selection Chart", designed for use by women from sixteen to forty-five. The gender of the forthcoming child could be determined by the year and month in which the woman became pregnant, so said believers, and the chart was closely coordinated with the traditional Chinese cosmology of yin and yang, the five elements and the eight hexagrams. Used originally by court ladies and high officials over 300 years ago, this method gradually made its way into the lives of the common people, and a new bride would often receive a chart from her family, in the hope she would soon produce a son and satisfy her parents-in-law.

Modern medicine has made great contributions to our understanding of this matter. Half a century ago, chromosomes were found responsible for determining gender, and no longer could mothers be held to blame for producing a line of daughters. The "culprit" was the father's sperm. Only if a mature X chromosome from the father matched the Y chromosome of the mother could a son be born.

The chances of producing a child of one sex over the other are just about even. Statistics put the world gender ratio of men to women at about 106 to 100. But because the distribution is uneven, some parents are satisfied, while others are left cursing their luck.

Nevertheless, the situation appears to be changing. In 1970, an American doctor, Landrum Shettles, wrote a book which offered parents a technique by which they could select their children's sex. The work soon became a bestseller. According to Shettles' theory, the relative alkalinity of a woman's reproductive tract during menstruation affected the speed of sperm carrying the X and Y chromosomes differently. X chromosomes, he said, flowed quicker when the alkalinity of the reproductive tract was relatively high. For couples wanting sons, use of vinegar douches and high consumption of green vegetables by the mother was recommended. Despite some early impressive statistics, critics later found serious problems in Shettles' theory, and now it is considered a set of harmless suggestions, still followed by many people.

Other doctors and scientists have tried to solve this puzzle, with Californian Ronald Ericsson being one of the most famous. Ericsson's family ran a cattle ranch, and the doctor spent considerable time and effort in trying to find a way to breed more males, whose meat is particularly prized by steak eaters. In 1970, he discovered that sperm could be carried in the protein of blood serum, in both cattle and people. In addition, sperm with the male chromosome was found to flow easier than that with the female chromosome. After separating the sperm, he then impregnated cows with the male sperm, which then gave birth to male steers four times out of five, with no birth defects. Three years later, Ericsson turned his attention to people. Between three to six injections were required for impregnation, and Ericsson declared a success rate of 80%.

In general, the normal male ejaculates 200 million spermatozoa at a time. If 80% are with the male chromosome, then 40 million female spermatozoa are left, with just one necessary to slip into the ovary and produce a baby girl. But still such odds look good for parents wanting a son, and beginning in 1981, several hospitals in Taiwan began using Ericsson's method. Many parents planned to have only two children, had already one daughter and wanted a boy. Others were in the position of Ms. Ch'en, with a succession of daughters but no sons, while some couples had yet to have a child.

However, doctors have one unwritten rule: only mothers with one or two daughters need apply. Women planning to have their first child are rejected as a rule. Those with many daughters are not encouraged to try, in keeping with general population control policy, but sometimes this rule is bent. One doctor recalls discouraging a woman who had taken the two-and-a-half hour bus ride from Ilan to Taipei. The woman had already had eight daughters, and upon leaving, said, "You won't help me, but that won't stop me from having more children." Caught in a quandary, the doctor decided to help the woman, improving her odds from a "natural" 50-50 to a "scientific" 75-25. In general, though, doctors warn against not seeing the forest for the trees, noting that access to this method on a large scale to mothers having their first child could result in unbalancing the gender ratio in Taiwan.

Legal measures have also been taken to weaken the preference for boys over girls. According to the present civil code in Taiwan, mothers without brothers can pass on their family name to their daughters, which also gives them a measure of property and economic independence.

At present some researchers and scientists are investigating the all-too-neglected other side of the problem: how to produce girls. Their efforts so far have yet to produce any concrete results, but then several people failed on the male side before Ericsson made his breakthrough, which still has its risks. Looked at from another angle though, there's no way parents can lose with a healthy, wanted baby, be it boy or girl.

(Mark Halperin)

[Picture Caption]

"With so many daughters, stop now and don't have any more children," urges a health worker to a mother.

Wanting sons but giving birth to daughters, Taiwan's families continue to have children at a high rate.

Impatient to know, many pregnant women are tested before birth to determine their baby's sex.

Bright and healthy children, be they sons or daughters, are always the apple of their parents' eye.

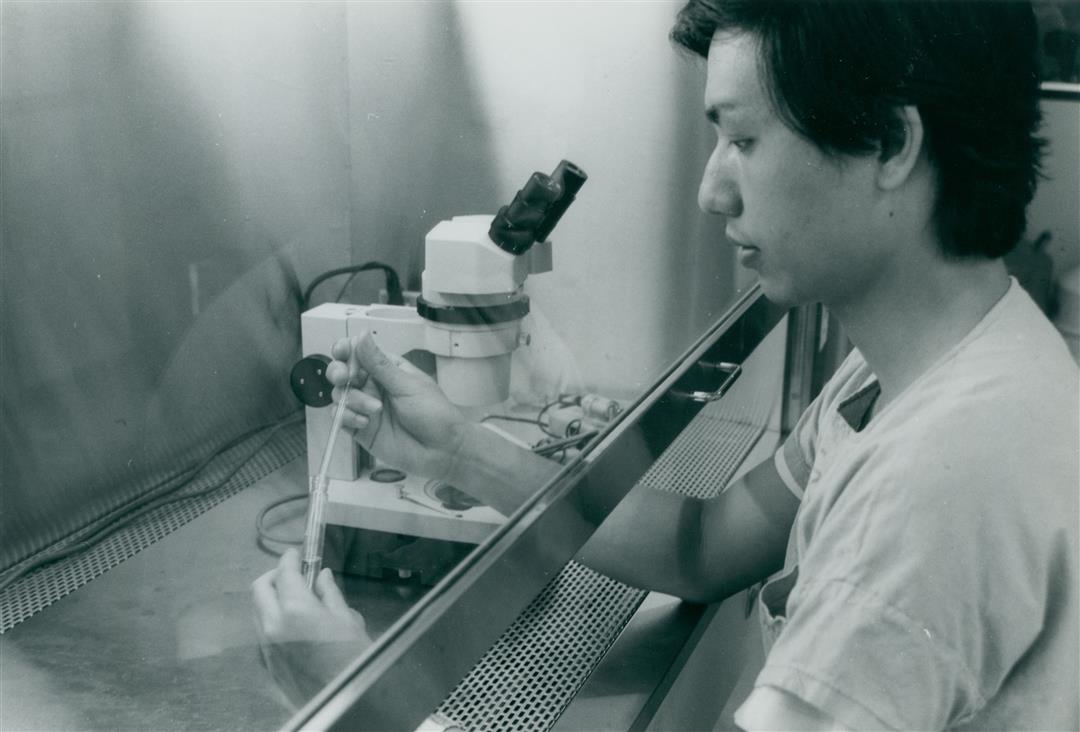

Jen Han-lang, hospital researcher, separates spermatozoa in a bacteria-free operating environment.

Palm reading is yet another way to predict a child's sex.

Mothers-to-be burn incense and pray for a son (or daughter).

Wanting sons but giving birth to daughters, Taiwan's families continue to have children at a high rate.

Impatient to know, many pregnant women are tested before birth to determine their baby's sex.

Bright and healthy children, be they sons or daughters, are always the apple of their parents' eye.

Jen Han-lang, hospital researcher, separates spermatozoa in a bacteria-free operating environment.

Mothers-to-be burn incense and pray for a son (or daughter).

Palm reading is yet another way to predict a child's sex.