From when the English produced "sharawadgi" in the early eighteenth century, to the energetic promotion of the Chinese style by William Chambers in the later 1700s, what were the real similarities and differences between Chinese and English landscape gardens?

"Not until the nineteenth century, when China's gates were forced," says one well-known scholar, "did the truth about her gardens leak out."

The "dreadful" truth?

The hero that revealed this truth was Britain, which "opened China's gates" with the Opium War and sent the plant hunter Robert Fortune there in 1843 to collect botanical specimens. In the records of his travels, it was Fortune who described the private garden of a certain physician, old Doctor Chang of Ningbo.

After passing through a number of halls in Doctor Chang's house, Fortune noted that the back garden where he rested during his retirement occupied a very restricted space. It used rocks, trees and archways to create the effect of a winding path with glimpses of different scenes. The "truth" that art historians have taken to be revealed by this description is that "the gardens of the mandarins were, by English standards, no more than suburban plots."

This truth has been passed down the generations in an unbroken chain. As one author puts it with complete confidence in a book published only a few years ago, when the gates of China were forced open in the nineteenth century, "the dreadful truth leaked out: the scale of the gardens of the mandarins compared to their equivalents in England rather as the bonsai does to the beech."

With such a world of difference between the Chinese and the English garden, the two should not be spoken of in the same breath.

Mountain buildings, myriad torrents

Having said this, though, it is hardly fair to compare an urban garden in Ningbo with the kind of English country park to be found at a place like Shugborough. After all, the origins of Chinese gardens go back a long way. They stretch from the Shang Lin Park of the Qin and Han dynasties (255 BC-AD 221) to the retreats of the literati of the Tang-dynasty (AD 618-907) and Song-dynasty (AD 960-1280), and up to the imperial parks and urban gardens of the Ming (AD 1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911). From the vast expanses of the imperial hunting grounds, to the naturalistic working gardens of the mountain scapes, and the one-acre and half-acre gardens of Suzhou, the differences are incalculable. How can foreign experts take the single example of Doctor Chang's back garden in Ningbo to represent the whole truth?

In a work on the Shang Lin Park, Sima Xiangru of the Western Han dynasty described the palace garden of Emperor Wu Di as containing eight gushing torrents, each flowing in a different direction, while a dense concentration of buildings covered the mountains and valleys. You really cannot say that such a garden does not have an air of grandeur about it. Yet Chinese gardens before the Tang and Song dynasties were all this expansive. They only began to shrink when the population became concentrated south of the Yangze and a bourgeois class arose during the Southern Sung (AD 1127-1280). It is worth noting that a similar process occurred in Britain with the transition to the urban society of the nineteenth-century Victorian era.

The large gardens of the Qin and Han dynasties, and the forest parks of the Tang are things of the past. What, though, if we make comparisons with the Qing-dynasty Yuan Mingyuan, also known as the Summer Palace, and the Imperial Park at Jehol that so captured the interest of the eighteenth-century Europeans? The former occupied 5200 acres in Peking, while the latter was even larger at 56,000 acres. When compared with the "English standard" of a few hundred acres for the country garden, which one is the "bonsai"?

Bare hills and stunted trees

Yet the foreign expert has more to say. She quotes the description by the missionary father Matteo Ripa of the Imperial Park as "Bare, hump-backed hills, sparsely clad with a few dejected and stunted trees" to tell us that it "looked nothing like the English home counties"!

As for the Summer Palace, having described how Burlington and Kent transformed the taste of the English garden according to the sentiments of the classical Roman country retreat, this author adds that, "Meanwhile in China, it seemed that the emperor was up to something similar." Quoting from a letter from the missionary priest Jean Attiret, which describes the winding paths and serpentine waterways that snake between the hills and rocks of the Summer Palace, she then quickly reminds the reader that what is being described here "is not Chiswick, but the great gardens of the Yuanming Yuan near Peking."

How is it that sometimes the Chinese garden "looked nothing like" the English garden, yet at other times it needs to be pointed out which type of garden is being talked about? The interest of the above author in the Summer Palace is not in its winding rivers and pathways, though, but in the pavilions that are located between them. As she explains: "To Western sensibilities, this garden architecture was undoubtedly less threatening than the untamed Chinese landscape."

A heaven for cows?

Chinese who have been threatened by foreign powers for over a hundred years are likely to be somewhat thick-skinned when walking in an English garden. Passing the flowers and trees, then coming across a small bridge over flowing water with a pavilion and drooping willow, though, one can still get the pleasant surprise of being near home. If you happen to go into the "Chinese Room" situated in the waterfront building and see some distorted Chinese characters reading "room to place the breast" (presumably meaning "milking parlor"), you are not so much threatened as bemused.

One Chinese writer of the 1930s who was walking through an English landscape garden wondered, on seeing the spreading slopes of grazing land, why civilized people should want to give up most of the land to green grass. "Without doubt, cows will love it. But what has it got to do with intelligent human beings?" he asked.

The doubts of this Chinese writer do in fact point to an obvious difference between the Chinese and the English garden-there is no lawn in the former. But a piece of grass actually represents one of the important aspects of the eighteenth-century English natural garden: economics.

For money-and fun

In comparison to the French formal palace garden, no matter whether in its creation or in its maintenance, the natural garden is related in a number of ways to the economy. The essayist Addison, who used the Chinese idea of nature to promote the English-style garden, grandly proposed that if a farm could be turned into a great park, one could both earn some money and enjoy some recreation.

In the past, a high fence had been used to prevent grazing animals getting into the garden proper. When the natural garden, with its irregular grassy area and waters, replaced the formal garden, a ditch was used instead.

Capability Brown's "improvements" led to the lawn becoming the main subject of the garden, stretching all the way up to the foot of the building. It is because of this that some scholars say that Brown seems to have "pastoralized" the whole garden.

This kind of economic art history can also find some confirmation in painting. In the scenery of the popular portrait paintings of eighteenth-century England, behind the landlord and his wife, is there not a neatly ordered piece of emerald grass with cows and sheep all in their proper places?

Although intelligent people do not eat grass, apart from the joy that comes from seeing the natural beauty of a scene of cows and sheep on wind-swept pastures, it is also reassuring to know that there is a flourishing agricultural economy and that wealth comes from the land. Who can complain? It is this custom of having a lawn in the garden that has been maintained in the West down to today, albeit on a smaller scale.

The garden as haven

It is when you look at the garden as a pastoral scene that some similarities between the Chinese and the English styles become apparent.

It was the poet Tao Yuan-ming, of the Eastern-Jin dynasty (AD 317-420), who advocated giving up one's official position and remuneration in favor of retreating to work in the garden, where one could enjoy writing poems by the river, stroking the pine trees and enjoying the life of the hermit. What encapsulated the ideal of the literati garden most was when he picked a chrysanthemum from under the bamboo fence and turned to see the mountain scenery. The vision of the pastoral garden with its rustic hut surrounded by a bamboo fence thus came to compete with that of the royal garden and its grand palaces. Later on, even the gardens of the Manchurian imperial household brimmed with the literati ethos, and the scene of the pastoral retreat became an indispensable element.

In eighteenth-century England, the advocates of the natural garden were mostly people in the political wilderness. Their attack on the formal palace garden was used to express their discontent with tyranny. Yet the natural garden, established as it was on the ideal of liberty, could also be used as their safe retreat from the world.

Lord Burlington's garden had many pagan Roman temples, giving it the feeling of being the retreat of the dissident. It seems that those who inspired the natural garden most hung up their official caps and left official life along with Burlington to create in the countryside a new style garden based on the themes of "liberty and tyranny."

The poet Alexander Pope was an early enthusiast for the Chinese view of nature and, with the help of Burlington, built a small garden on the bank of the winding Thames river in the south London suburbs. It had no fence, parallel paths or symmetrical flower beds. He planned to make it a place where he could engage in literary and artistic pursuits.

In the end he was so proud of it that he began selling his own tickets to sightseers. Pope never thought that they would become so numerous as to disturb his poetic reveries. He finally had to shut himself away in the most secluded part of the garden to write poetry in a room just big enough to move in. Perhaps the desire to go back to nature, combined with an inability to give up the ways of the world, is a common trait of all people, whether Chinese or Western.

Responding to the surroundings

In the whole revolution of the natural garden, though, Pope was a luminary. He seems to have been involved in all the important early eighteenth-century gardens and to have left his poems behind. His notion that you should "first consult the genius of the place" is easy to link with the idea of "responding to the surroundings" in the theory of Chinese gardening.

Pope also had a theory that all gardens should be landscape paintings. Burlington's good companion, Kent, was in fact not a "gardener" originally but a painter. There is much similarity between such a view and the Chinese sentiments of "poetry in the scenery," and "scenery like a painting."

William Shenstone was another eighteenth-century poet who converted his country park into a natural landscape garden. This included a circular road that passed through 40 different scenes, including "China's Vain Alcoves." His hope was that walkers would feel as though they were in an epic poem or drama and that Arcadian sentiments would be the result.

The garden at Stourhead, which still exists today, also shows the design of an eighteenth-century amateur gardener who modeled its features on Virgil's epic poem, the Aeneid.

It might be pure coincidence that there were forty scenes in Shenstone's garden and forty in the Summer Palace. Yet the use of garden architecture to create scenic features or viewing places for the pursuit of poetic emotions and combining art with nature, is the common dream of garden walkers in China and the West. Aside from this, though, at the same time as the creators of Chinese gardens were finding their "soul," they would also give that soul a name, just to put the finishing touch to the picture.

Different land spirits

When the Da Guan garden was finished in the Qing-dynasty novel Dream of the Red Chambers, Jia Zheng said, ". . . such grand vistas and so many pavilions, without inscriptions this scenery will not flourish."

The quarters of the characters Bao Yu and Bao Chai in the same book are named in terms of cheerful colors and fragrant plants. Scenes from the Imperial Park at Jehol are summed up by the phrases "plum blossoms, crescent moon," "serpentine water and lotus fragrance," "wind, spring and tranquil listening," and "snow weaving over the south mountains." What you will find inscribed in the English garden is "Temple of Bacchus," "Temple of Venus," "Gothic Tower," "Temple of Victory and Concord." In the end, then, the soul of the land in China and the West is different. Where does this difference lie?

The new style of English garden departed from the constraints of the formal garden and knocked down its perimeter wall so as to pursue nature's untrammeled beauty. What, then, were the temples, grottoes and ruins in these gardens meant to express?

When Virgil's Aeneas is shipwrecked in a country that he fears is inhabited by barbarians, he looks around and sees some figures carved in relief and sighs, "These men know the paths of life, and mortal things touch their hearts."

This is the difference between the civilized and the barbaric. Eighteenth century England was certainly full of vigor. Yet perhaps the essential quality required to be civilized is a deep sense of permanence, an escape from the immediate world. It is the feeling that, as the art historian Kenneth Clarke puts it, "in space and time one consciously looks forward and looks back." It is thus that the English gardeners borrowed from ancient Rome, and placed "ancient sites" and even "ruins" in their gardens.

Natural or not?

The problem is that this fashion very quickly became formalistic as the trickle turned into a flood. Capability Brown's "minimalism" might have had something to do with this. With one hand he got rid of what remained of the formal garden, while with the other he cleared out what was ostentatious in the natural garden.

Today, Chambers' reliance on China can be seen to have been well-intentioned. What he advocated so vigorously was nothing more than the perfect combination of art and nature. He always stressed that the Chinese did not completely reject straight lines and formal patterns. As well as imitating nature, he knew that Heaven's techniques must be stolen in order to imitate Heaven's work.

Some Western theorists at that time were of the opinion that the Chinese accepted the use of straight lines and formal patterns in the layout of cities and palaces, to order relationships between people, and to express the human will. Yet when handling the relationship between people and nature, even the Chinese emperor himself, whose domains were far more extensive than those of even Louis XIV, treated it as an equal partner and did not presume to lay claim to sovereignty over that domain.

Could it be said, though, that in the Summer Palace at Peking and the Imperial Park, sites which became so famous in the West, the Chinese emperors did actually "presume to lay claim to sovereignty over nature"?

Southern scenery in a northern garden

After the first Qing dynasty emperor Xun Zhi came from Manchuria to China proper, the Emperor Kang Xi was enthroned and made two tours of the south, where he absorbed the beautiful scenery of the literati. When his rule had been settled and the financial conditions were right, he had the idea of rebuilding southern China in the north.

The Summer Palace at Peking and the Imperial Park, which were built in the eighteenth century, were the results of the creation of mountains and control of water needed to recreate the southern scenery in the north, and the gathering together of the best scenery by the most excellent masters of Chinese gardening. Westerners had in fact seen thirty-six of the scenes from the Imperial Park from the engravings of the missionary Matteo Ripa, which were boundless but "obviously inhabited." In fact, the park covered 560 hectares. It miraculously created out of the rocky north nature's intricate work of the southern Chinese scenery. And the whole park was surrounded by a wall.

The most obvious difference between the Chinese garden and its English counterpart is probably to be found in this long and winding perimeter wall. At the other end of the world in the eighteenth century, the literary circle of Kent and Burlington had just "discovered" nature by going leaping over the fences that had surrounded their well-ordered flower beds.

What was the Chinese emperor "up to" at this time? He was leisurely gathering the natural splendors between heaven and earth to put within the walls of his palace!

p.29

Is comparing the Chinese garden to its Western counterpart like distinguishing between the bonsai and the mighty beech? The Lin Family Garden at Panchiao (left) and England's Painshill. (photo by Hu Ke-li)

p.30

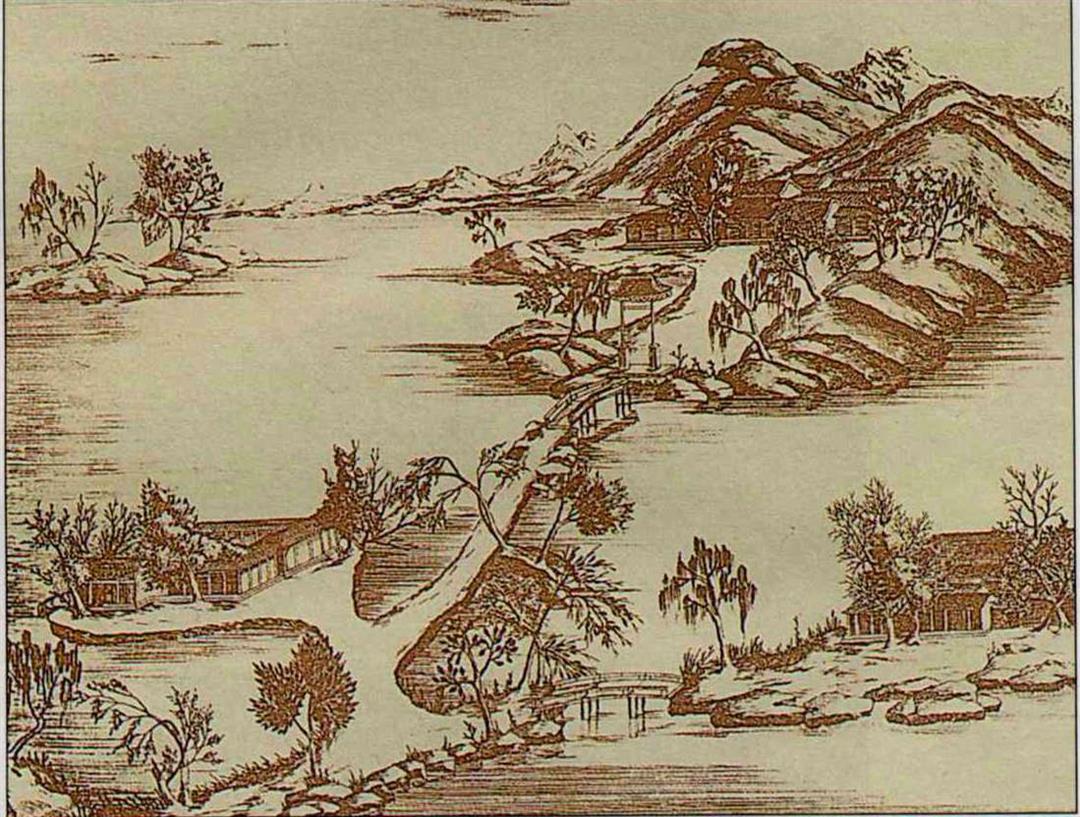

Winding shores and mystical islands joined by small bridges in a scene from the Imperial Park at Jehol, engraved by the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ripa.

p.31

A Chinese bridge spans the water at Painshill. (photo by Hu Ke-li)

p.32

All brand new? A fake ruin can still provide that ancient touch in the garden at Shugborough, England.

p.33

Emerald grass at Shugborough. A heaven for cows-or a paradise for people?

p.35

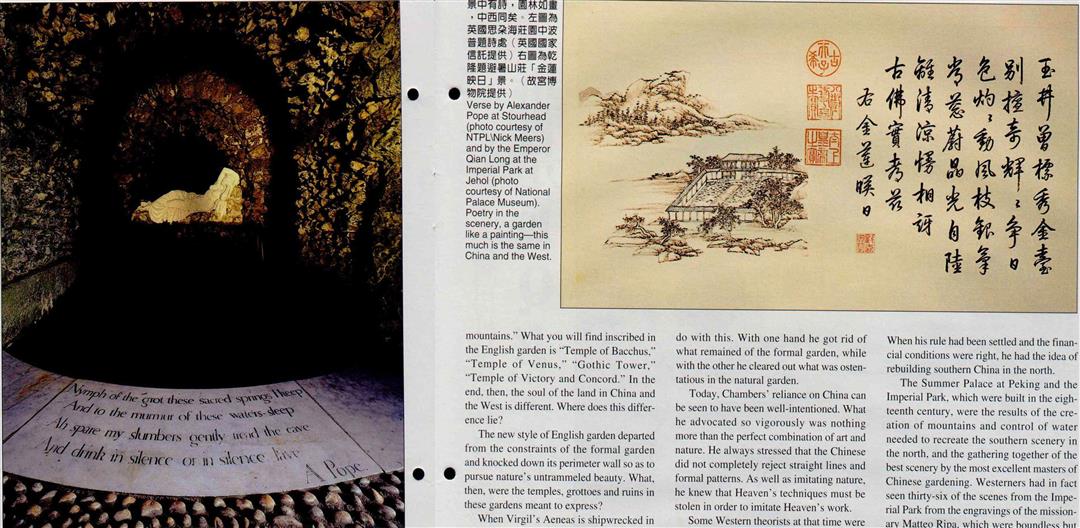

Verse by Alexander Pope at Stourhead (photo courtesy of NTPL\Nick Meers) and by the Emperor Qian Long at the Imperial Park at Jehol (photo courtesy of National Palace Museum). Poetry in the scenery, a garden like a painting-this much is the same in China and the West.

Winding shores and mystical islands joined by small bridges in a scene from the Imperial Park at Jehol, engraved by the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ripa.

A Chinese bridge spans the water at Painshill. (photo by Hu Ke-li)

All brand new? A fake ruin can still provide that ancient touch in the garden at Shugborough, England.

Emerald grass at Shugborough. A heaven for cows--or a paradise for people?

Verse by Alexander Pope at Stourhead (photo courtesy of NTPL\Nick Meers) and by the Emperor Qian Long at the Imperial Park at Jehol (photo courtesy of National Palace Museum). Poetry in the scenery, a garden like a painting--this much is the same in China and the West.