Chengkung is 130 kilometers south of Hualien and 60 kilometers north of Taitung, making it a natural rest stop for travelers along the southeast coast, "the last pristine place on Taiwan."

As a result, this "little village," nearly one half the size of Taipei in area but almost a hundred times smaller in population, frequently has two or three tour buses pulled up at its only filling station. The passengers sometimes get out to buy some dried fish, the noted local product, before taking off in their buses down the road, but they don't even eat here: everybody thinks the food in Taitung is better.

People come and go but the impression that Chengkung leaves with most of them is just a stretch of road, some dried fish shops, and a row of little houses between the mountains and the sea.

No one expected that Chengkung would become so famous because of a bridge.

"I got letters from friends I hadn't heard from in thirty years," says Wang Ho-sheng, secretary of the township administration, who spoke a few words about the "bridge incident" on TV.

The "bridge incident" arose because of Chengkung's most important tourist resource: Sanhsientai.

Sanhsientai, to the north of Chengkung, is a piece of coral reef pushed up by changes in the earth's crust. Because it's uninhabited, the little island is rich in plant life; its 28 hectares are home to over 200 species. And the view of the Pacific is magnificent. For the past thirty years, the people of Chengkung have been trying to think of how to turn Sanhsientai into a tourist attraction.

The problem is that Sanhsientai is about 120 meters offshore. At low tide the water comes up to a person's knees, and at high tide it's over one's head. The idea of building a bridge was first suggested about seven or eight years ago. "It wasn't just for tourism but also for safety," Sung Wen-ying, the town's mayor, explains. Sanhsientai is a good place for fishing, and fishermen wading over and back were sometimes caught in the tide.

The mayor and the town council wanted a bridge, although a few of the locals, like the teachers at Hsinkang Junior High, were not too keen on the idea. The nation's ecologists, on the other hand, were incensed. "Without a bridge, it's lovely; with a bridge, it's vulgar," one indignant scholar sniffed.

Despite the controversy and conflicting signals from government agencies, work got under way, and the bridge was completed this September. Yet many scholars remain adamant. A member of Academia Sinica says that the bridge is "an inappropriate construction" and should be torn down immediately.

The town had more problems with a refreshment center it built last year. They had originally wanted to put it by the shore where most of the tourists would be, because "that's the way they did it at Maopitou." But the experts felt that it would spoil the scenery so they moved it uphill. The lovely traditional Chinese-style structure now stands impressively on a distant hill, but it's empty: the concessions moved out for lack of business.

And a restroom that the town had put up near the parking lot was criticized as "blocking the view." "We spent NT$50,000 to put it up, and NT$100,000 to tear it down," Wang Ho-sheng laments. "We're afraid to make any more suggestions-- everything gets nixed upstairs. We might as well just push brooms."

And the media attention produced some unfavorable consequences. A TV report that some special stones on the island were aromatic and good for the complexion caused a search craze "They'd jump out of the tour buses and grab them by the handful, and they'd sneak up at night and haul them away in trucks," the island's manager says. "It was too much!"

Some anglers, careless in starting a fire burned the island's woods to cinders, and the specimens of a rare plant that used to grow there, the haimei or "seaplum," were all dug up and have disappeared.

In view of the destruction, the Taitung County government has drawn up a plan to restrict entry to the island and enforce strict regulations on visitors.

Actually, Chengkung has more resources than just Sanhsientai. Farmers grow persimmons, oranges, and papayas on the hillsides and corn, rice, and peanuts in terraced fields. But harvests are highly irregular. Streams are rapid and shallow, the moist sea wind beats down the crops, and about ten typhoons slam into the coast each year, sometimes cutting off the town for days at a stretch.

Fortunately, the typhoon season lasts only four months--and the town has a fishing industry.

Over 5,000 tons of fish a year are caught in Chengkung, making it the second largest fishing center on the eastern coast, next to Suao. The main species are bonito, swordfish, tuna, and sardines. The bonito are sold as ch'aiyu, a variety of hard dried fish which is the town's most noted product. Ten or twenty years ago, the town had several dozen ch'aiyu factories, but because of unstable supply and poor prices, only two remain.

Chengkung's fith hatcheries raise mostly molluscs and prawns. More and more hatcheries have sprung up in recent years as fish farmers expelled from the Northeast Point have moved in to take advantage of the area's clean air and water. When the Ministry of Interior in 1983 designated Chengkung and two other townships on the east coast as scenic protection areas, it banned new hatcheries except in certain areas specially set aside for fish raising, but the number continues to grow. There are around thirty now, only five of which are legal.

The mountains west of Chengkung are rich in mineral deposits, chiefly dolomite and limestone. The stone quarries and open-pit mines defacing the mountainsides may cause soil erosion and spoil the scenery, but they also provide jobs.

Development bears a price, but without it, where will young people find work? A study by the local fishing council reveals that the median age of the town's fishing crews is getting older and older.

On the other hand, many outsiders are drawn to the area by its scenic beauty and the wholesome environment and come to live here. Of the twenty-some out-of- town teachers sent to teach at one of the local junior high schools, for example, over half have decided to remain.

The people who move to Chengkung like the fresh air, the peace and quiet, the simple ways of the people, and the superb natural beauty. They have chosen another life-style, another set of values, and Chengkung suits them just fine.

[Picture Caption]

This is the bridge that caused all the commotion and made Chengkung famous. In the background is Sanhsientai.

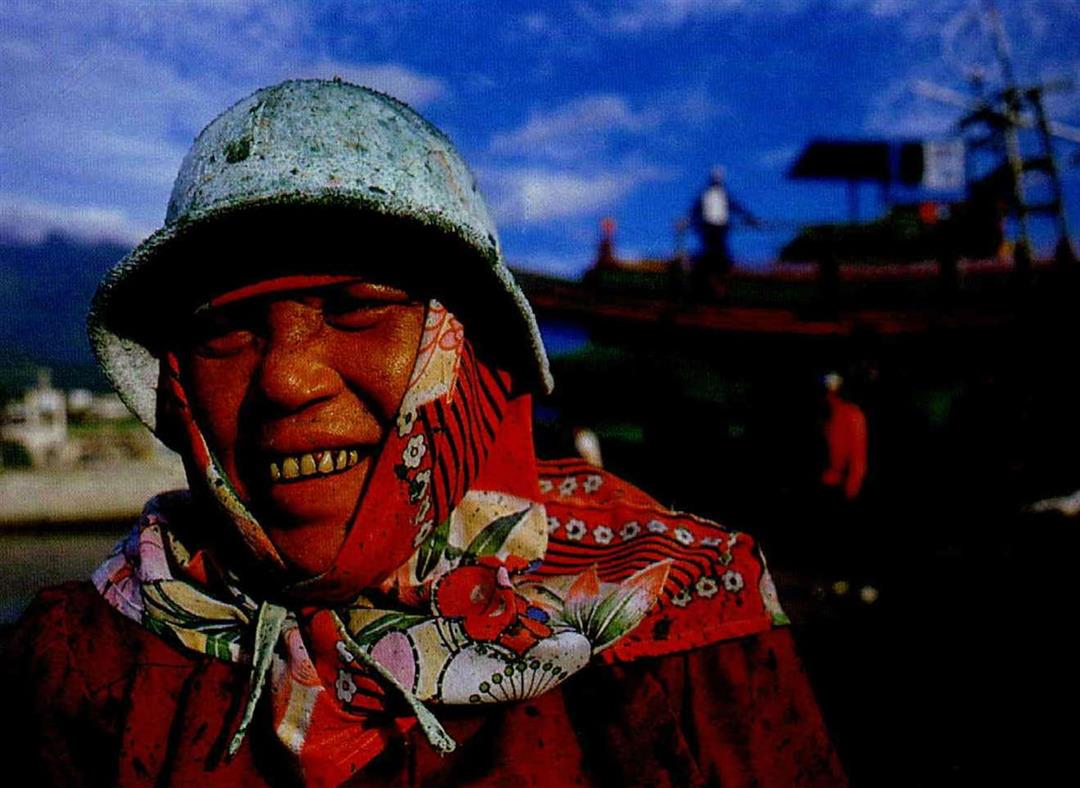

Tanned, healthy, and radiant--the face of a typical Chengkung native.

This farmer is holding a peanut plant, one of the major crops grown on hillsides in the township.

After processing, these swordfish will sell for a NT$30, 000 to NT$40,000 (around US$1,000 to US$1.300) each. Most are exported to Japan, where they are eaten as sashimi.

We chased them for over a kilometer to take this one! The fishermen are headed for the ocean to go to work.

(Above) Fish hatcheries bring wealth but spoil the coast.

(Below) The woods on Sanhsientai burned down in a fire.

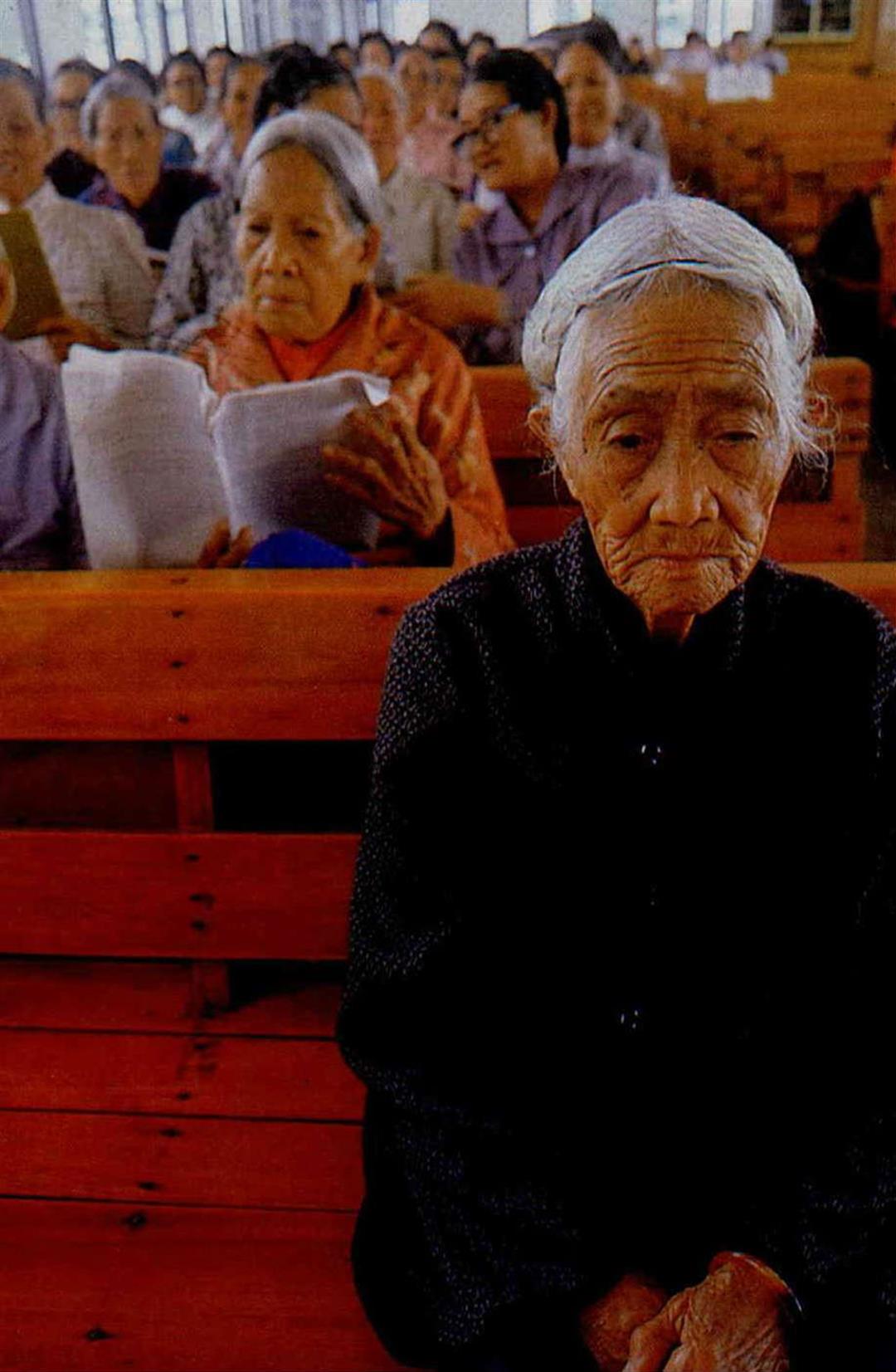

Sunday service at a Christian church in Sanmin, the village in the township with the largest aboriginal population.

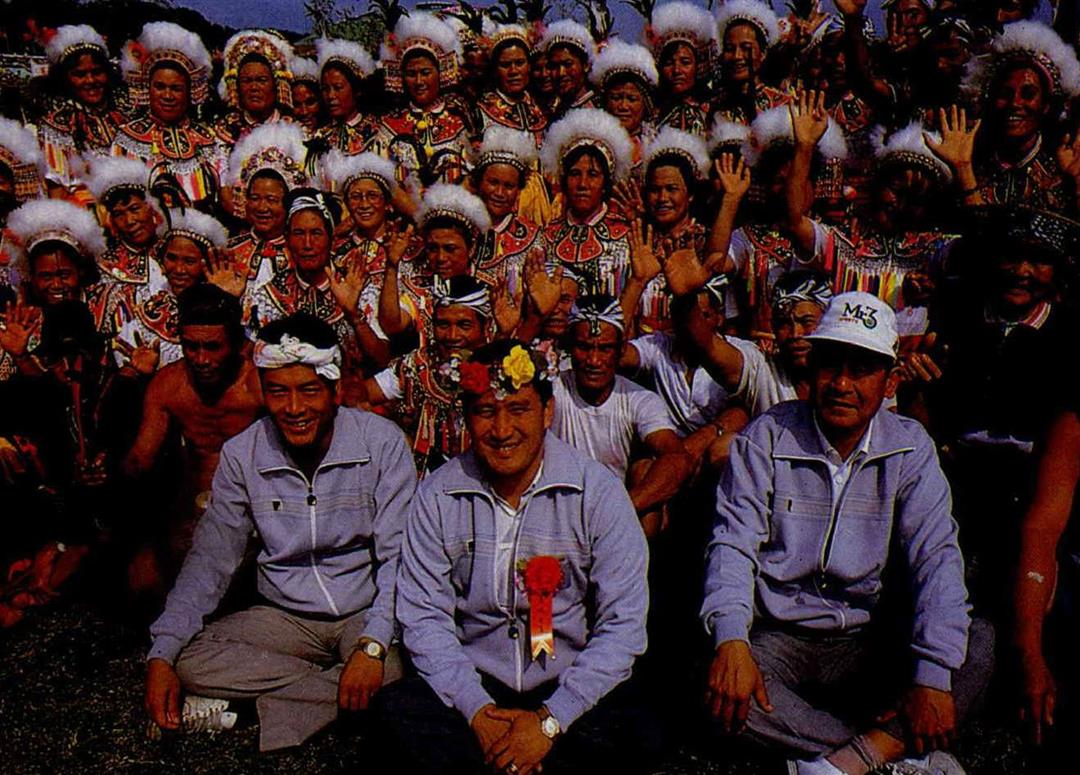

Ami aborigines gathered for a folk dance smile for the camera. In the middle at front is Sung Wen-ying, the mayor, and to his left is Wang Ho-sheng, the township's administrative secretary.

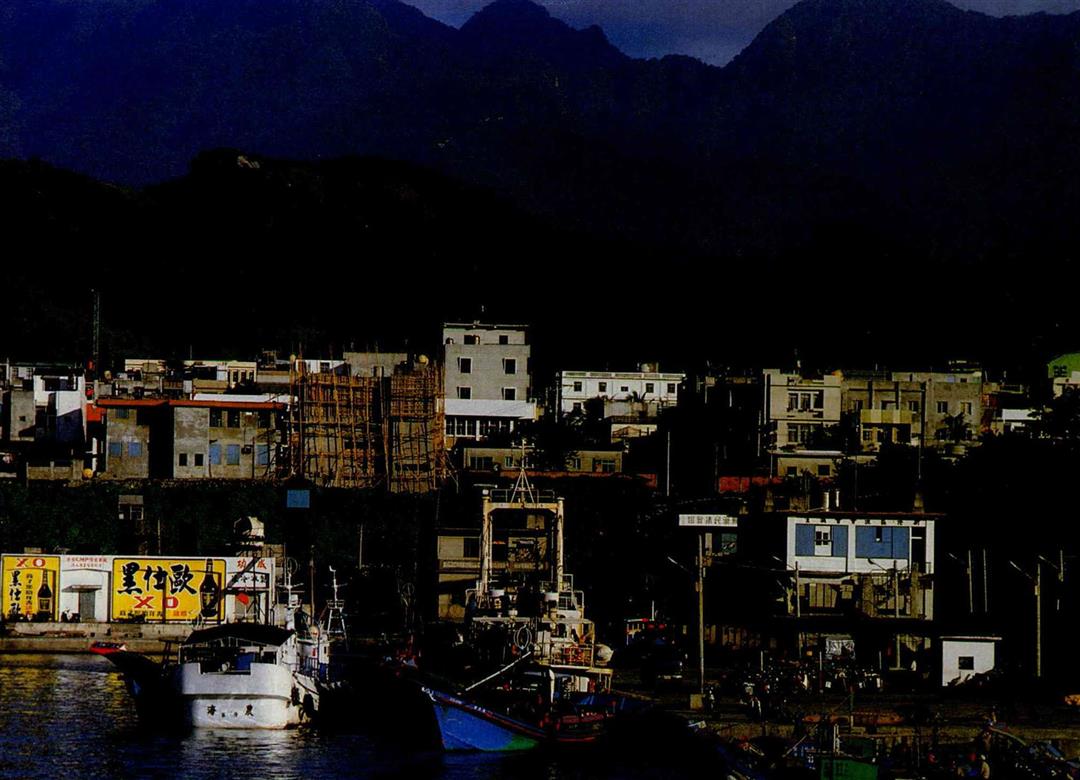

Green mountains, a fishing harbor, and a feeling of peace and quiet--that's Chengkung.

Tanned, healthy, and radiant--the face of a typical Chengkung native.

This farmer is holding a peanut plant, one of the major crops grown on hillsides in the township.

After processing, these swordfish will sell for a NT$30, 000 to NT$40,000 (around US$1,000 to US$1.300) each. Most are exported to Japan, where they are eaten as sashimi.

We chased them for over a kilometer to take this one! The fishermen are headed for the ocean to go to work.

(Above) Fish hatcheries bring wealth but spoil the coast.

(Below) The woods on Sanhsientai burned down in a fire.

Sunday service at a Christian church in Sanmin, the village in the township with the largest aboriginal population.

Ami aborigines gathered for a folk dance smile for the camera. In the middle at front is Sung Wen-ying, the mayor, and to his left is Wang Ho-sheng, the township's administrative secretary.

Green mountains, a fishing harbor, and a feeling of peace and quiet--that's Chengkung.