On June 15, 2005, photographer Yeh Ching-fang died of liver failure at age 45.

Born in Jueifang Township, Taipei County, Yeh made a name for himself in photography circles at an early age. By 1982, when he was a student of photojournalism at Shih Hsin University, Yeh had already traveled far and wide to take photos. During a visit to the zoo, he spotted an owl and a child staring at each other through the glass of the aviary; the resulting image, with its reflection in the glass, is an odd chimera of animal and human, the two merging into a single surreal whole. This photo was the most defining of Yeh's career, winning him the gold medal in the black-and-white division of the National Colleges Photography Contest that year, and marking the beginnings of the style and attitude of his future photography career.

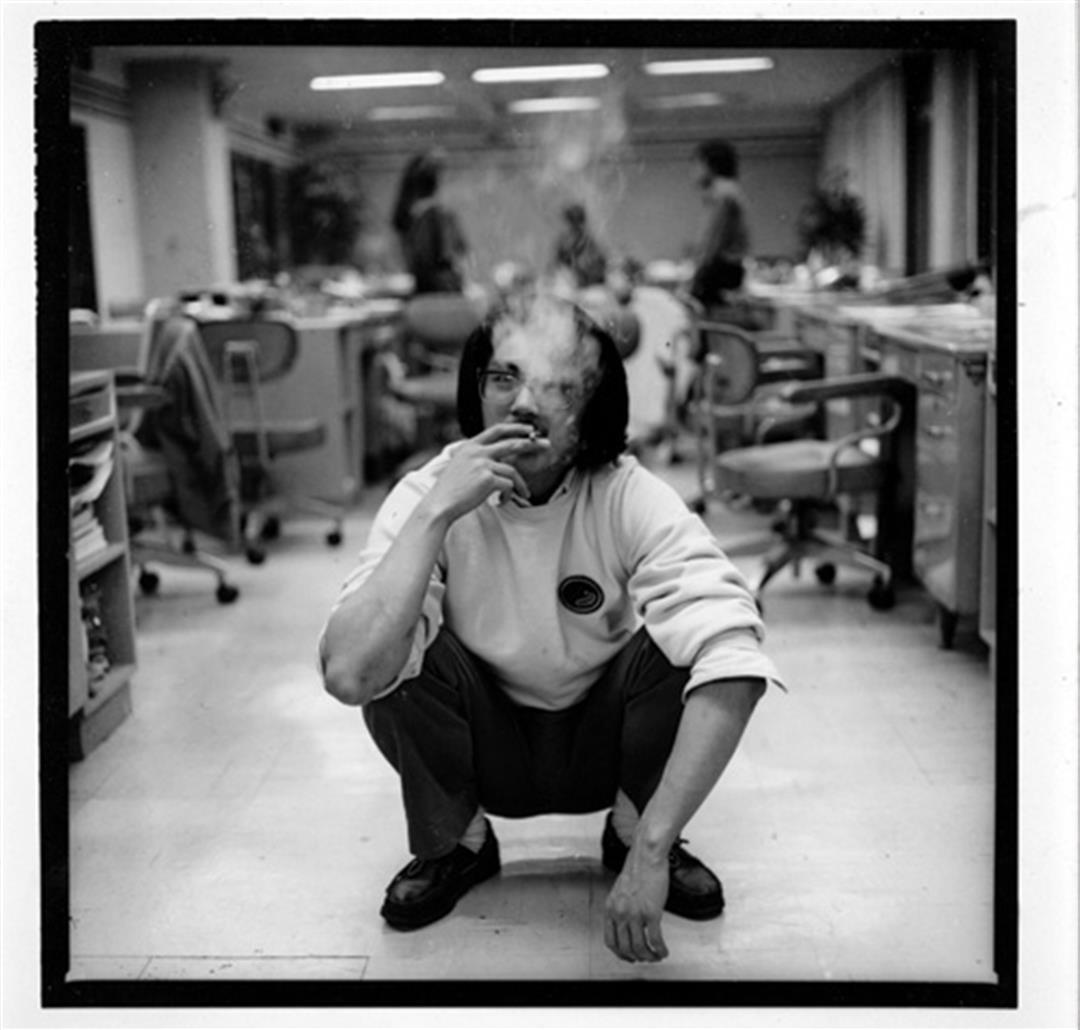

After completing his military service, Yeh worked for publications like the China Times and China Times Weekly, and through his years in these jobs he traveled widely, including visits around Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China. His photographic style changed with time, with his works including street photography, black-and-white shots, pinhole photography, and graffiti. But his most iconic works are his monochromatic photos documenting Taiwanese society in the 1980s.

The 1980s, in the final days of martial law, were a vibrant and confusing period of transition for Taiwan's society. The uneasy, tumultuous, and confused atmosphere of the times permeates Yeh's work. The people in his photographs--male or female, young or old--all give off a sense of the loneliness, nihilism, and eeriness of the times. They all seem like they're looking for something, but at a second look, they seem to have given up and have no sentimental attachments at all.

Yeh's casual personal style also shows through in his works, in his use of odd angles and his out-of-focus shots. One example is a portrait shot of three girls--the shot is dim and hard to make out, but still shows a certain unique sophistication. In another photo, a news shot taken at a campaign rally, Yeh used a slow shutter speed, and with the bright lights at the event, this created an unreal, trancelike effect. These techniques, which are unusual in the world of photography, give Yeh's work a unique visual style.

Photographer Chang Chao-tang, reviewing the photos from the rise of the new wave of master photographers in the 80s, wrote: "Through their use of crude directness, degradation, and black-and-white imagery, the photographer captures the spontaneity of the world around us. By adopting a skeptical perspective, they reveal the gloomy feelings of the solitary and the young." Such is the description of a photo of the youthful, suspicious faces of three young adults in Jueifang train station, which recalls another image of the Kaohsiung coastline, where three middle-aged men smoke and stare, puzzled, into the hazy distance. Behind them sits an overturned, abandoned boat, which can no longer be used.

When fellow photographers remember Yeh, they remember a man like the aloof, depressed subjects of that photo--introverted, quiet, and a man of few words. Recently Yeh's friends have begun collecting his works, and they expect to be able to open a memorial exhibition on the first anniversary of his passing, bidding farewell to a friend and photographer who passed in the prime of his life.

Self-portrait shot by Yeh Ching-fang during his time at the China Times Weekly.