Who needs a party, anyway?

After the dissolution of the TPP, Chiang Wei-shui issued a declaration in which he stated: "This order to disband can be seen as a glorious death in battle. No longer is there any need to organize the shell of a political party, because the party we want is banned by the government, while the party the government will allow is nothing but empty skin with no meat and bones." He felt that with public opinion behind him, he could be just as effective with no formal party organization, relying on peripheral organizations that had been affiliated with the TPP to carry on his "nationalist movement with a core made up of the peasantry and working class."

Tragically, Chiang Wei-shui not long thereafter came down with typhoid fever; he died on August 5th of that year, aged 40 years and five months. On his deathbed, Chiang called on his comrades to "unite and continue to struggle" to win liberation for their compatriots.

As Huang Huang-hsiung sums it up, "Over the course of his ten-year struggle, Chiang Wei-shui not only became a core figure in Taiwan's political and social movements, but gained a reputation among the people as 'the savior of Taiwan.'" When the newspapers reported his death, people were deeply shocked and saddened, with some even donning black armbands in mourning. An estimated 5,000 people attended his funeral, with the procession winding from Tataocheng to the mountains around Tachih, an unprecedented honor. "There is no other figure from the Japanese colonial era whose death caused such profound sorrow and sense of loss among the people of Taiwan," says Huang.

With the disbanding of the TPP and Chiang's death, the political and social movements in Taiwan lost their direction. Many TPP cadres emigrated to mainland China, the TCA survived but its educational and cultural work was very low-key and could only have an impact in the very long run, and the Alliance for Self-Government in Taiwan confined itself to rhetoric and wishful thinking. Later, as the influence of militarists in Tokyo grew, Japan tightened the screws on its colonies, and the decade of nonviolent Taiwanese resistance against Japanese colonial rule came to a close.

Looking back on this stretch of history, historians give the highest possible evaluation to Chiang Wei-shui for his influence on Taiwan's cultural enlightenment movement and his contributions to political and social reform. Under an oppressive colonial regime, his high level of consciousness inspired other Taiwanese to stand up and be counted, and his courageous, can-do spirit fills one with admiration even today. Is it not time that another generation of Taiwanese share in the collective memory of this man?

Chiang Wei-shui: A Chronology

1891 Born in Ilan County

1906 Enters Ilan Public High School

1910 Enters Taipei Medical School

1915 Graduates from medical school #2 in his class

1916 Opens Ta-an Clinic in Tataocheng

1921 Joins the petition campaign for a Taiwan elected assemblyFounds Taiwan Cultural Association, publishes "A Just Diagnosis"

1923 Taiwan Minpao founded in Tokyo; Taiwan branch established, with Chiang in charge "Social Order and Police Incident" occurs

1924 Imprisoned for the first time; studies extensively while incarcerated

1925 Imprisoned for the second time; continues his studies Sales of Taiwan Minpao surpass 10,000 "Erhlin Incident" occurs

1926 Chiang opens Wenhua Shuju (Culture Bookstore) Publishes "The Left-Right Debate"

1927 (Jan) Taiwan Cultural Association fragments Publishes "A Nationalist Movement Based on the Farming and Working Classes" (Jul) Founding of the Taiwan People's Party

1928 Creation of the General Alliance of Taiwan Workers

1929 Chiang leads campaign against opium permits

1930 Taiwan People's Party fragments, Alliance for Self-Government founded

"Wushe Incident" occurs

1931 Taiwan People's Party forced to disband by colonial authorities

Chiang dies of illness

Chart by Coral Lee based on information from Huang Huang-hsiung, A Biography of Chiang Wei-shui.

This commemorative photo was taken as Chiang lay near death. The sad faces of the comrades and family members surrounding him betray not only their grief over his condition, but seem to be saying that Taiwan's nonviolent resistance movement was also fast approaching its end. (courtesy of Chiang Sung-hui)

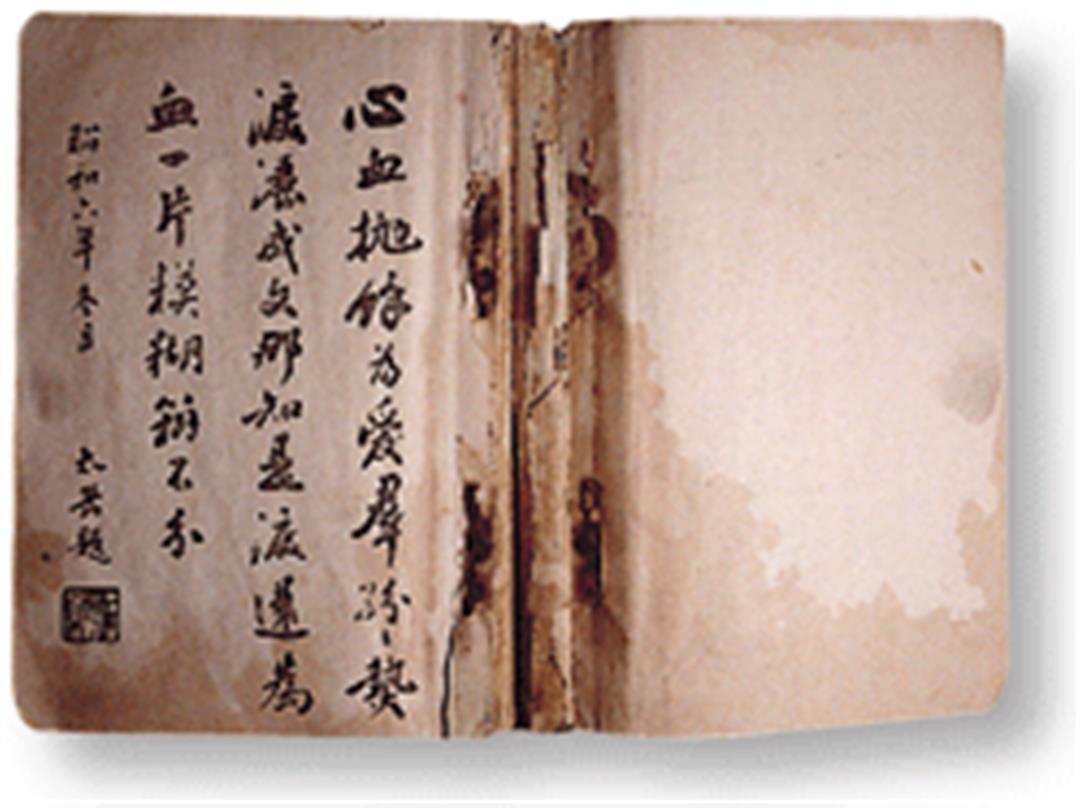

After Chiang's death his comrades-in-arms tried to publish The Complete Works of Chiang Wei-shui, but it was confiscated at the printer's by the Japanese police. The photo shows pages from the only remaining copy, the note by Chuang Tai-yueh. (courtesy of Lin Tsai-mei, wife of Tai Kuo-hui)

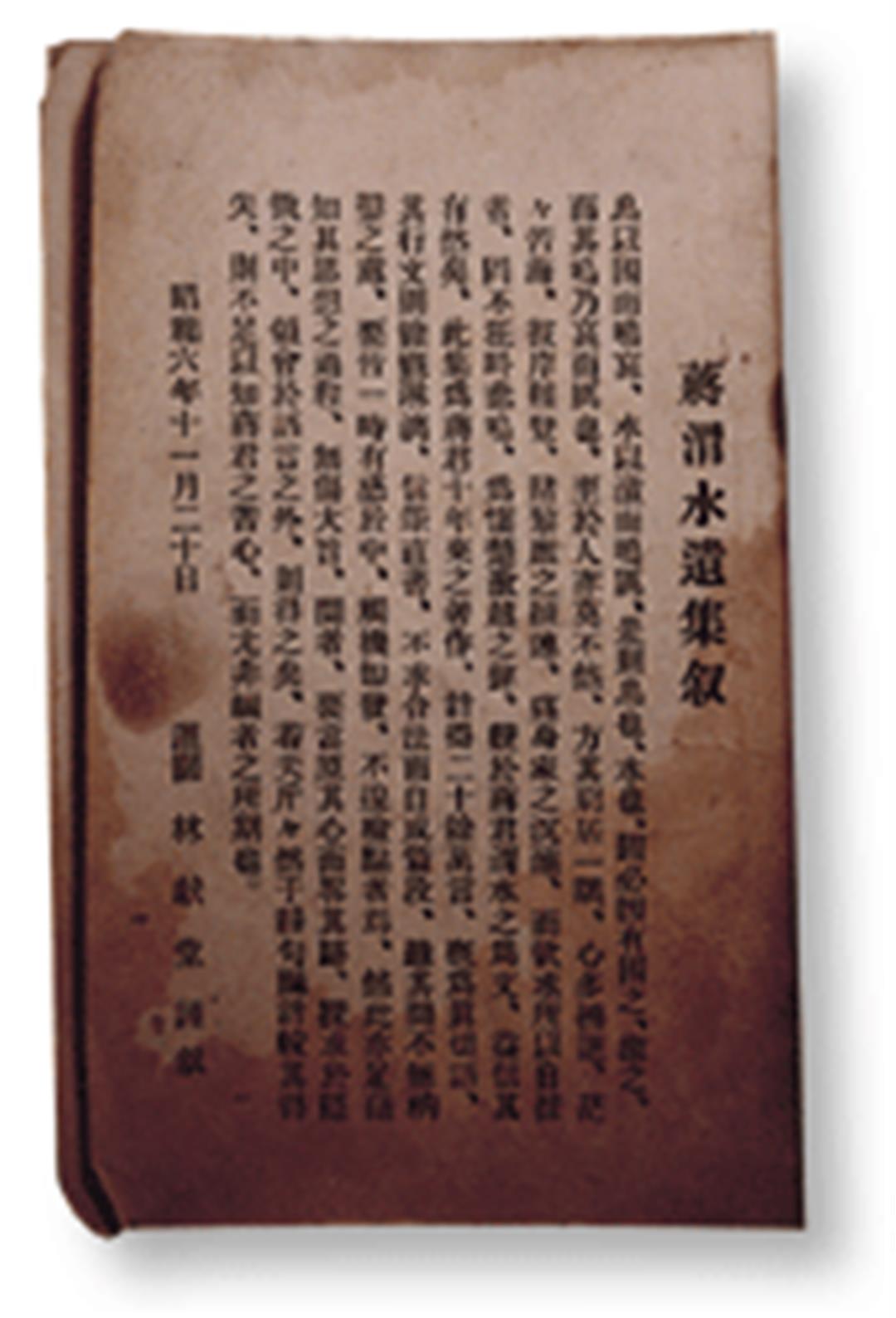

After Chiang's death his comrades-in-arms tried to publish The Complete Works of Chiang Wei-shui, but it was confiscated at the printer's by the Japanese police. The photo shows pages from the only remaining copy, including the foreword by Lin Hsien-tang. (courtesy of Lin Tsai-mei, wife of Tai Kuo-hui)