The Rise and Fall of the Taiwan Provincial Government

Jackie Chen / photos Vincent Chang / tr. by Willie Johns

January 1999

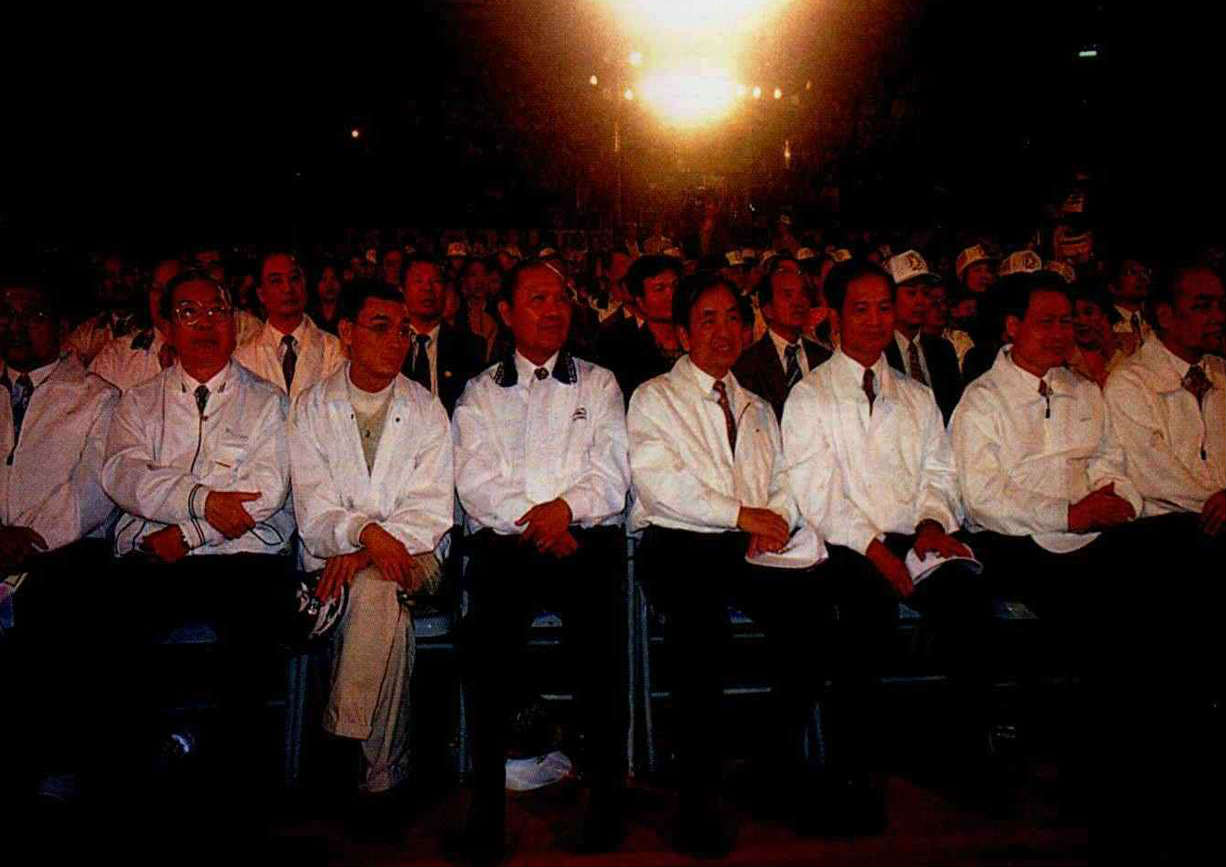

Before downsizing took effect, James Soong, the last provincial governor, visited all the cities and counties under TPG administration to report on the results of promulgation of TPG policies. At the "thank-you" dinner banquets that wrapped up each visit, the "TPG Team," wearing their standard white windbreakers and highly-polished black shoes, conveyed their best wishes to the citizens of the province.

Is the Taiwan Provincial Government history? With its downsizing, the four familiar tiers of ROC government will still exist, but the content of what each does is changing. How has this massive and controversial reconfiguration of government come about? And once the downsizing of the provincial government is complete, what exactly will the lay of the political land be?

In December of 1998, there was a strong sense of an era coming to an end.

On the 20th, James Soong spent his last day as Taiwan Provincial Governor at Chunghsing Village, where provincial employees bade him farewell by embracing him, giving him flowers and singing him songs. Soong, who was visibly moved as he read his "We'll Meet Again" good-bye speech, remarked that he was the "first and last elected governor of Taiwan." But his wasn't the only post being eliminated. The Taiwan Provincial Government (TPG), which had been responsible for provincial matters for 52 years, ceased its operations, and the "Transitional Provincial Government," with responsibility for streamlining the provincial bureaucracy, took over.

The day before, Liu Ping-wei, the last speaker of the Taiwan Provincial Assembly, slammed down his gavel at 10:43 a.m., at which time Huang Min-kung, the assembly's last secretary, read the "Proclamation Announcing the Dissolution of the Taiwan Provincial Assembly." The assembly hall echoed with the notes of a farewell song, and then members exchanged keepsakes and stood for a group photo. The highest provincial representative body in Taiwan, which had developed over the course of half a century, attaining legislative and budgetary powers, was being disbanded. A provincial consultative council took its place.

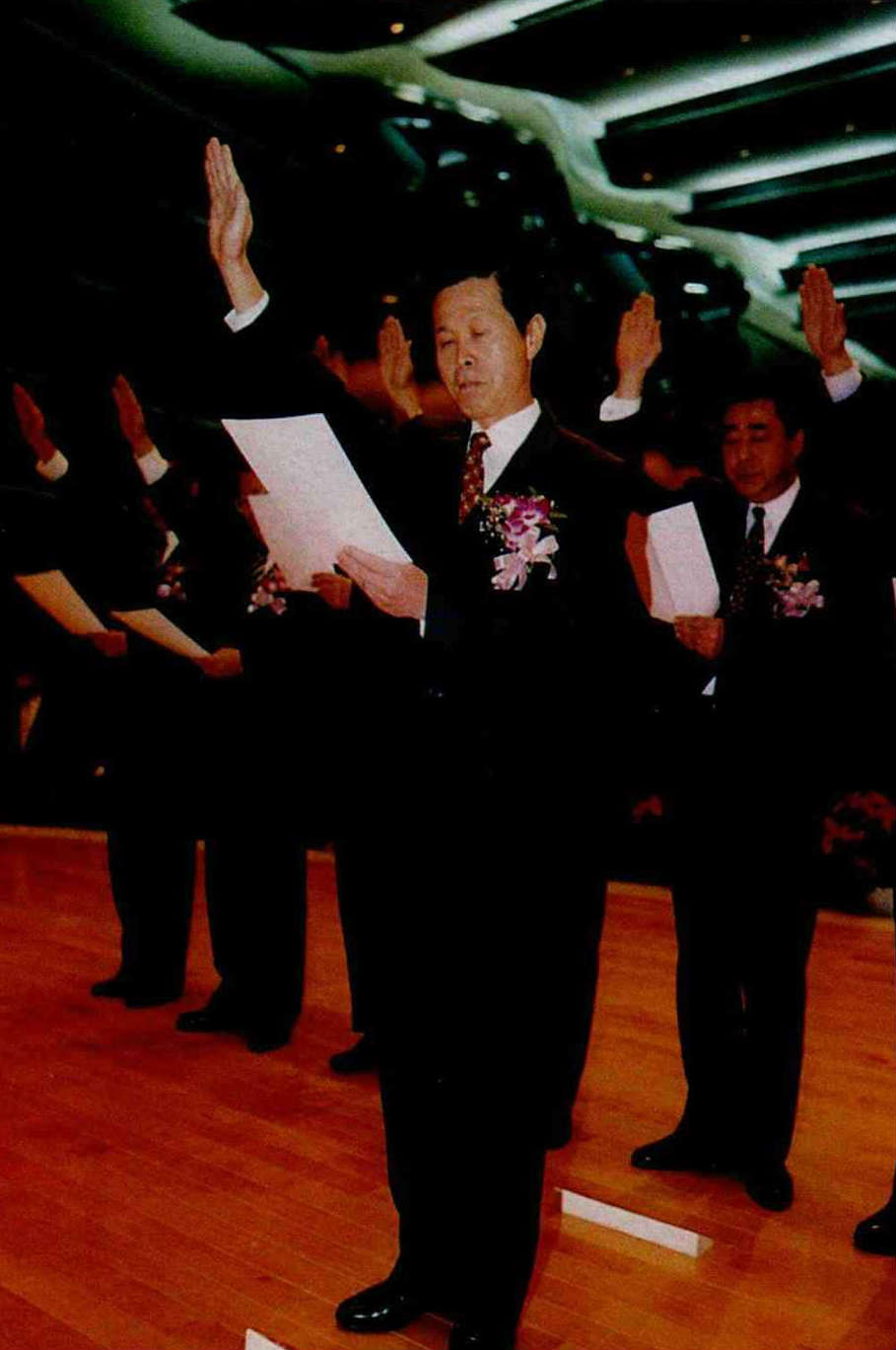

On December 22, 1998, Chao Shou-po, the newly appointed provincial chairman, took up his post. He immediately announced that provincial policy marked something completely new for the nation which would take a great deal of patience, will and attention to detail. (photo by Cheng Lu-chung)

These changes triggered a new wave of nostalgia. Invitations to the assembly, assembly awards and commemorative coins, copies of its official gazette, records of its debates, official provincial government sweatshirts, and even souvenir "governor's hats" all became sought-after collectibles. In the days and months previous, the papers had been filled with headlines such as "The Last Provincial Art Exhibition" or "The Provincial Orchestra Plays Its Last Tune."Key project

The TPG is indeed soon to be history!

Since the ROC government moved to Taiwan in 1949, the ROC has had four tiers of government: the central government, the provincial government (and governments of the special administrative cities of Kaohsiung and Taipei), county and city governments, and the governments of urban and rural townships. How exactly are the provincial agencies going to be downsized? What will the old Taiwan Provincial Government turn into? These issues are rooted in the half a century of history since the ROC government moved to Taiwan, and involve the issues of local self-governance and of overlapping and redundant government authority. Downsizing plans have been the subject of incessant debate both inside and outside the government. "If done well, downsizing will give a facelift to government organization," says one political observer. "If done poorly, it will make an even bigger mess of the relationship between central and local government."

The four-tier government structure used in Taiwan over the last half century is basically the same system that was in place on the mainland before the Communist rebellion and the retrocession of Taiwan. But up until the Self-Governance Law for Provinces and Counties was passed in 1994, constitutional requirements about local self-governance were not being met, and the provincial governor took orders from central government bureaucrats. Many scholars of public administration viewed the arrangement as unconstitutional.

In July of 1994, the self-governance law was passed, and elections for the mayors of Kaohsiung and Taipei Cities and the provincial governor came at the end of the year. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) described these elections as "the first war in 400 years." At that point all four tiers of government had been given a solid basis in law. Yet with a few exceptions such as national defense and foreign policy, which were clearly the responsibility of the central government, there were many gray areas in which the respective responsibilities of the central and local governments were left undelineated. In particular, there seemed to be no way to resolve the 90% overlap between the duties of the provincial and central governments. This duplication of responsibilities was a time bomb just waiting to explode.

Over the course of half a century the TPG served as the head of 21 city and county governments. Whenever a locality experienced a problem, it turned first to the provincial government. On December 11, on a farewell visit to Kaohsiung, even Kaohsiung County Magistrate Yu Cheng-hsian, a member of the opposition DPP, was in attendance.

Provincial governors were originally appointed by the central government and had to obey their appointers' orders about budgets and personnel, explains Chiu Chang-tai, a professor of public administration at National Chung-hsing University. But once the governor stood for election he became indebted and responsible to the voters, and was under pressure from the electorate to deliver on his promises. Resolving just exactly who was boss-the central government or the provincial government-became more and more pressing.817 stamps

Many problems arose from insufficient funding at the local level. Say local governments lacked money to lay a road or build a bridge or take necessary measures to implement national development policy on such matters as universal health insurance, welfare for the elderly and farmers, or smaller classes and schools. If their requests for central government assistance were then denied because of "overall considerations in light of the national budget deficit," then the provincial government, which saw itself as the head of a dragon whose body consisted of its 21 counties and cities, would roar. The papers were filled with reports about disagreements between central and provincial authorities.

In most people's eyes, the biggest problem caused by overlapping authority was the strange phenomenon of everyone "grabbing for the good and playing hot potato with the bad." Last fall, when a typhoon caused flooding in Hsichih in Taipei County, the central government argued that funding for dredging the Keelung River was long ago budgeted, but that the local government had not handled it according to plan. The local government, on the other hand, held that the problems were a result of difficulties in acquiring the land necessary to meet city planning requirements and in finding sites to dump the dredged sediment. Each side clung to its own view of things.

Premier Vincent Siew noted that current government regulations often state that "the responsible authorities are such-and-such a unit in the central government, the provincial government at the provincial level, and the county and city governments at the local level." It sounds like there are a lot of people in charge, but as soon as something goes wrong, they all flee from responsibility.

Past efforts to prevent corruption by lengthening lines of decision-making did indeed hurt government efficiency, to an extent that is hard to fathom in this competitive age. In a cabinet meeting in 1996, then-Premier Lien Chan bemoaned that it took 817 different stamps from government agencies to process the paperwork for Hualien's Ocean Park. He suggested that the ROC might try looking abroad to find better models. "There isn't another government in the world that requires requests to be approved by so many different people," says Wu Yao-fung, head of personnel for the provincial government. It's like having only one worker on an assembly line but many supervisors. The government, of course, wants to rectify this problem, and downsizing the provincial government will help.

But the speed with which the government went ahead with its downsizing plans is largely attributable to the political environment.

Under the Self-Governance Law for Provinces and Counties, the Taiwan Provincial Government is to be eliminated. So on December 19, 1998, the TPG held a huge "going away" bash.

Public administration scholars had long been proposing various solutions to the problem of overlap between the central and provincial governments. Some suggested dividing the province into several separate zones with fairly equal areas and populations. Many argued all along that the provincial government should be stripped of all real power or abolished outright. But because the government previously still claimed authority over mainland China (so that in a reunited China Taiwan would end up as only one of many provinces), and because over the course of half a century thousands of provincial regulations had already been put into place, it was thought that just junking the TPG outright would be too difficult. Hence, even though political scientists at the high-level national policy conference in late 1990 advocated stripping the provincial government of all its real power, so that it would exist in name only, the prevailing position within the government was to retain the TPG and reconfigure the political map in a way that would help bring about local self-governance.The Yeltsin effect?

Then, with the first elections for the provincial governor at the end of 1994 and the first presidential elections in 1996, the problem of overlapping authority once again came to the fore. Chi Chun-chen, director of the civil affairs department at the Ministry of the Interior, says frankly that the elimination of the provincial government became necessary to prevent a "Yeltsin effect." "It was in response to changes in the political environment."

The provincial government was of a different opinion. In regard to the "Yeltsin effect," former-Governor James Soong argued that in the current political environment it would hardly be likely that the ROC president and Taiwan provincial governor would come from different political parties. "Taiwan Province is a stable force within the ROC, and is not resisting ROC authority," stressed Soong at a meeting of the National Development Conference attended by high-level bureaucrats and party officials. And he argued that blame for the government's administrative inefficiency could not wholly be laid at the door of the provincial government: "The paperwork for managing water resources now goes from the TPG over to the cabinet, where it gets bumped back and forth among the Ministry of Economic Affairs, the Council for Economic Planning and Development, the Council of Agriculture, and the Industrial Development Bureau. If the provincial government gets cut out of the loop, the process is still going to be inefficient." Soong argued that apart from putting a vertical emphasis on reducing the layers of government, it was equally important to put a horizontal emphasis on fighting problems that crop up at the same level of government.

But regardless of what the provincial government says, the downsizing has already started. According to the plans prepared by Chi Chun-chen, the future provincial government will be organized around "three different bureaus, with a total of seven departments, three offices, and one committee, and an on-assignment unit that enjoys the same status as a bureau." Twenty-nine currently existing departments will be completely abolished.

In accordance with the provincial downsizing regulations passed by the Legislative Yuan in October of last year, it is certain that the provincial government will lose its powers to budget, hold assets, legislate, hire personnel and levy taxes that are enjoyed by autonomous local governments. Instead, it will become more like another cabinet ministry.

These plans have a clear goal: to greatly reduce the scope of the provincial government after downsizing. Yet the grand justices of the Judicial Yuan have ruled that the provincial government will still have the "public corporate body" status of a local government. After downsizing, it will still have power to oversee county and city governments. Chao Shou-po, the new provincial chairman, says that the provincial government will move toward serving as a bridge between the central and county governments.

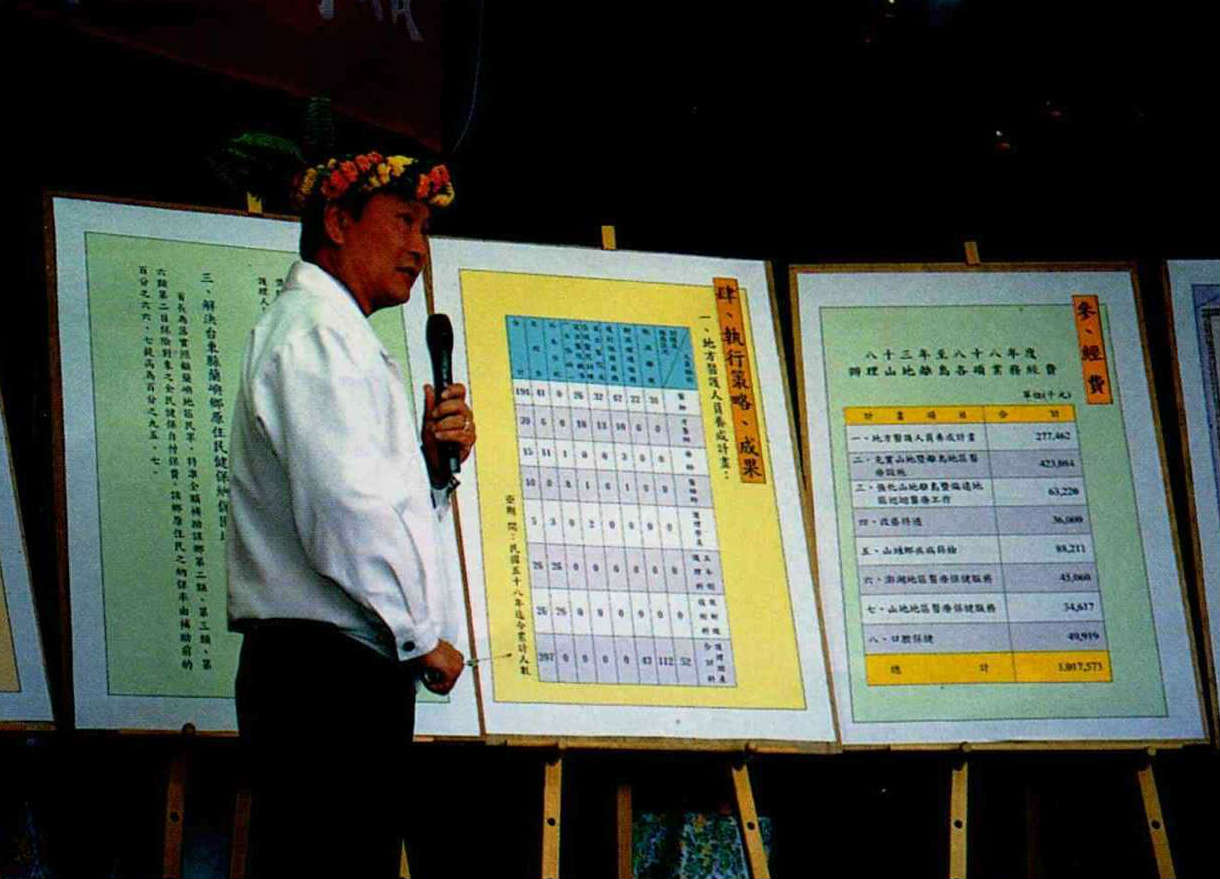

At Taiwan Provincial Fengshan Hospital, Shih Yao-tang, the commissioner of the Taiwan Provincial Department of Health, gives a briefing about the "Plan for Guaranteed Healthcare in Mountain Areas and Outlying Islands." Under the administration of the provincial government, there was a wide gulf between the services available in the cities and in rural areas. Choosing what measures can be taken to narrow this gap after the downsizing of the provincial government poses a great challenge.

What will be the actual fate of the provincial government? Will it become like the Fukien Provincial Government, existing in name only with no real powers, or will it still enjoy some of the autonomous characteristics of local governments? Today, it appears that various options are still open.Integration and coordination

After developing for more than half a century, the TPG became more than merely a spokesman for the interests of 21 counties and cities; to a large degree it served to coordinate projects that involved several local governments. "When cities and counties started quarreling with one another, their first reaction was always to call in the provincial government," says Wu Sung-lin, director of economic research for the provincial government. "When local governments start directly appealing to the central government to sort out problems involving sewers, roads and so forth, who knows how they will be able to handle it?"

For example, when Tapi Rural Township in Yunlin County approved plans for a pickled vegetable processing plant, the neighboring township of Hsikou in Chiayi County protested that the plant's waste water would pollute the river that flowed between the towns. Similar problems occurred when weirs were built along rivers in Chichi in Nantou County, but the waters of the Choushui River were to be shared with Changhua and Yunlin; or when Tainan wanted to build the Nanhua Reservoir and bring in water from Kaohsiung's Chishan River; or when weirs were proposed for the upper stretches of the Kaoping River, so that water could be diverted from Pingtung to Kaohsiung. When such projects are proposed, local governments with resources tend to take the attitude, "Why should you get to use our water?" These situations require a mediating third party.

The provincial government used to frequently play the role of a coordinating facilitator, "persuading one party and reassuring another." How will this work be done in the future? "Can it be that in addition to the involvement of the Ministry of the Interior, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Ministry of Finance and the Council of Agriculture there will also have to be a special government coordinator appointed?" asks Li Hung-yuan, head of the Water Resources Bureau.

Some people respond that there's no reason to assume that central government agencies lack the ability to coordinate. "Look at the big problems being dealt with by government today, such as the enterovirus scare and disputes over garbage incineration. Don't these require central government agencies to send their own people out into the field?" asks Chi Chun-chen. But there are also people who believe that the old system for seconding central government workers to local governments was poorly executed, and that as a result those making policy in the central government have scant experience with local affairs.

All schools in Taiwan Province at the high school level and below (some 6000 in all) are under the control of the provincial government. It is still uncertain whether control over them will go to the central or local governments after provincial government downsizing. The photo shows provincial officials celebrating at the opening of a high school in Sanchung, Taipei County.

Today, civil servants have much too little room for advancement in county and city governments, where clerks at the 10th grade can go no farther. If two classmates pass civil service exams the same year and then one works for the central government and the other for local government, ten years later the one working in Taipei might have already been promoted to the 12th grade, whereas the classmate working in local government will still be stuck in grade eight as a section chief, with no chance for advancement. "There will be simply no post for him to advance to," says Wu Sung-lin. Because this situation is so prevalent, it is always difficult to get central government workers to accept "taking a step down" to local government posts.Experienced specialists

"The more experienced we are, the meeker we become," says Wu. With the rising power of the local governments, the process of carrying out plans is not as pure and simple as most policymakers would like to think. Take the recently opened ten-kilometer Taichung-Nantou Highway, which passes through a city and two counties and which drew more than 10 bids for its construction. It wasn't discovered until shortly before the road was to open that asphalt wasn't available. Urgent pleas had to be made to China Petroleum. Then it turned out that there wasn't enough power, and the provincial government immediately appealed to the chairman of Taiwan Power, who told the company's central Taiwan operations office to provide assistance. Then, to install traffic lights, the provincial government had to bring together and coordinate between the separate police departments of the three different local governments. There are always many such details to resolve. It's never just a matter of "getting the budget allocation and then being able to assume that the project will be completed before the deadline," he says.

Then there's the case of Hsiaoliuchiu Island, off the coast of Pingtung. In the past, there wasn't a single gas station on the island, and residents who needed gasoline for their motorcycles or farming equipment had to cross the water to Tungkang. Every family had two tanks in their house for storing petrol.

"It was like keeping two bombs in your home!" exclaims Wu. Why couldn't a gas station be set up on the island? The provincial government discovered that the sticking point was obtaining the land. If suitable sites weren't on national government land, then they were owned by temples. But after the provincial government negotiated with the National Property Bureau and discussed the matter with local residents, the island was finally able to get its gas station. "These aren't huge things, like one of the 12 major national development projects," says Wu. "But they require long-term interaction with the localities. The provincial government has been doing this sort of stuff for half a century."

After the downsizing of the provincial government, the provincial assembly is being replaced by a new purely advisory council. The site of the old provincial assembly is being turned into the Provincial Assembly Memorial Park Area. There are plans to develop a Museum of Local Self-Governance and other facilities here. The photo was taken on December 18, 1998. The provincial assembly had already ceased operations, and opening ceremonies for the memorial park were being held.

Chiu Chang-tai believes that after the downsizing of the provincial government, duties of this type involving coordination among several local governments will still need to be handled by the provincial government. For projects involving water resources and waste disposal, which are highly technical matters, the provincial government, after dealing with such problems for many years, has put together teams that do their jobs quickly and well. There's no reason to disband them after provincial downsizing. Downsizing's three phases

The TPG has grown over its half century of existence. When established in 1947, it consisted of 14 departments. It now is a huge organization of 29 departments and some 129,000 employees. The public is concerned about issues raised by the downsizing, including the fate of TPG's employees and whether Nantou County's Chunghsing Village, where the TPG is based, will continue to exist.

According to the Executive Yuan's plan, downsizing will be divided into three phases. During the first phase, which runs from 21 December 1998 to the end of June 1999, the Executive Yuan will appoint a provincial chairman and establish a provincial council, all of the TPG departments and bureaus will continue to operate as they have in the past, and the provincial chairman will be responsible for completing the transitional budget and carrying out the legal and organizational transitions. The second phase will run from July of 1999 to the end of the year 2000. During this one-and-a-half-year period, adjustments to the provincial government duties and organization will be completed, as will the transfer of provincial government personnel. The beginning of 2001 marks the end of the transitional period and a return to local autonomy.

The new provincial chairman, Chao Shou-po, says that the TPG will be under the Executive Yuan. If their duties necessitate it, some of the Executive Yuan's departments and commissions, such as the Council of Agriculture, the Council of Aboriginal Affairs and the Ministry of Economic Affairs' Bureau of Water Resources, may be moved to Chunghsing Village in the future. The Executive Yuan has already set a precedent by setting up a Southern Taiwan Unified Services Center in Kaohsiung. In the future, it could also establish a similar center in Chunghsing Village to provide better services to central Taiwan.

Employees of provincial-level agencies will be settled into new positions as necessitated by the redistribution of the TPG's duties. Those with sufficient years of service will be encouraged to take early retirement with a generous severance package-for example, staff who have served 20 years who wish to take early retirement will receive a lump sum severance payment equal to 12 months' salary. In addition, the government will do its utmost to find positions for those who wish to continue working in the government. "In the course of the downsizing and discussions with the central government, it has been the guarantees offered to TPG employees that have achieved the highest degree of consensus," says Wu Yau-fong, director of TPG's personnel department.

The objective of downsizing the provincial government is to reduce the number of levels of government and red tape. According to the Executive Yuan's current plan, not only will Chunghsing Village be preserved, but TPG employees will also be absorbed by the central government. Local governmental bodies, and the TPG's power to set policies, make laws and create budgets, will be eliminated. However, based on interpellation of the downsizing policy by the grand justices, the TPG's power to monitor city and county governments will be maintained. This leaves some people wondering what is actually getting cut.

A cocktail party was held after the closing of the provincial assembly, and Hsieh Tung-min, who was speaker of the third and fourth assemblies, came. The elderly Hsieh's presence provided a certain sense of historical continuity.

Minister of the Interior Huang Chu-wen has said in an interview that the downsizing of the TPG is a gradual process and cannot be carried out overnight. "The whole process is being implemented very slowly," says Huang. The central government itself is also downsizing. According to a draft proposal on central government staffing levels, in the future the central government will cut back from its current level of 160,000-170,000 employees to around 120,000. When TPG employees are transferred, the number of central government employees will increase. To bring this number down, in the future many government employees will not be replaced when they retire. On the structural level, it is hoped that the work of many government bureaus and departments can be combined as in the case of the TPG's Water Resources Department and the Bureau of Water Resources, thereby reducing the number of levels and offices of the government.Raising the status of cities and counties

No matter whether you believe that the TPG was created for ideological reasons, to secure political stability or to improve administrative efficiency, the fact is that it has existed for more than 50 years. With Taiwan now fully committed to democratization, with a directly elected president, and with the political reality being that the ROC government governs only Taiwan, Kinmen, Matsu and the Pescadores, there is a great deal of overlap between the powers of the provincial government and those of the central government. This is obviously not beneficial to the nation's development in an era of global competition. It is thus essential that the government trim its size.

One can see that an entirely new map of the administration of the ROC is being created. Especially noteworthy is that a complete redistribution of power and money between the central government and local governments is being carried out.

Political science's most basic definition of local autonomy is the use of local people and the allowing of local self-governance wherein local people's wishes are obeyed in resolving local problems. However, this has not been put into practice on Taiwan since the ROC Constitution came into force. "The tendency in the past was to stress the power of the central government. This limited the power and capabilities of local government," says Woody Cheng,chief of the history teaching section at Feng Chia University. In Cheng's opinion, the "patriarchal" political structure had the effect of turning government bodies below the provincial-government level into powerless "daughters-in-law;" dependent upon the "patriarch's" mood for their own allocations of money and power.

Having relied on the care and attention of the government bodies above them for decades, local governments now lack the ability to handle affairs on their own. After the TPG is downsized, a completely new relationship with local governments will emerge. In particular, a four-tier system of government will be simplified to three tiers. As such, a focus of much attention is whether city and county governments can, like those of Taipei and Kaohsiung Cities (which are directly administered by the central government), take on more personnel and financial responsibilities.

Although city and county governments under the TPG were self-governing bodies before the implementation of downsizing, their status was much lower than that of Taipei and Kaohsiung. In the latter cities, the highest-level bureaucrats were accorded the status of high-ranking officials, and the mayor has full power to assemble his own team to implement his policies. In contrast, the highest-level bureaucrats in the municipal and county governments under the TPG were required to have passed the civil service examination, effectively tying the hands of mayors and magistrates when it came to choosing personnel. In some cases, there were even instances of such mayors and magistrates having to wrestle for control with persons from different parties on their administrations, leading to difficulties implementing policies.

Chi Chun-chen says that according to the draft localization bill sent to the Legislative Yuan, which defines the division of power between local governments and the central government, and related bills, in the future mayors and county magistrates will have more power to choose their own staffs. Now not only will a deputy position of political officer be established under mayors and county magistrates, mayors and county magistrates will also be allowed to appoint five senior-level staff members that need not be drawn from the civil service. In addition, these five senior staffers will see their civil service grade raised. Finally, mayors, county magistrates and their administrative deputies will have their civil service grades raised by at least one level. It is hoped that such changes will encourage talented people to work in local government and raise the morale of those already employed there.

When the functions of the TPG are changed, the structure of local representative bodies will also change. The Taiwan Provincial Assembly will become an consultative council of 26, all appointed by the Executive Yuan. It will no longer have the power to review legislation and budgets, and will instead have only the power to advise. Many former assembly members have now changed tracks, becoming members of the Legislative Yuan, and some pundits are already predicting that numerous local affairs will be raised in the legislature. Whether lower-level measures related to localization of government can be implemented smoothly remains to be seen. These lower-level measures include the consensus reached by the National Development Conference on downsizing the TPG, making the jobs of village chief and township chief into positions appointed by the central government rather than elected by the public, and ending elections for village and township councils.

Many are worried that parochialism may become more apparent when tasks that were originally handled by the TPG are handed over to local governments. Local tasks that the central government used to delegate to the TPG, such as the planning and design of urban roads, will most likely be turned over to local governments in the future. "Local governments don't have the ability to carry out such tasks, and there are no measures in place to prevent the long-criticized problems of 'dirty money' and local interest groups from interfering," says Chih Mei-chiang, a professor in the department of public administration at Tunghai University. Another worry is that 46 provincial assembly members entering the legislature might turn it into an arena for the divvying up of spoils, instead of a body dedicated to monitoring the operations of the entire government.

The Provincial Assembly Building has a mosaic in the floor of its lobby so that people entering walk over a dragon, the traditional symbol of the emperor. This represents authoritarianism being replaced by democracy.

Chunghsing University's Chiu Chang-tai believes that given the powerful position that today's city and county leaders hold, it might be best if hospitals, schools and social welfare organizations were still handled by the national government. His concern is: "How do you guarantee that Changhua County won't decide that its social welfare organizations and schools are for the use of its people only, and that people from Taichung, for example, cannot use them?"A battle over money and power

The central government and local governments are not only working out how to divide power. Another issue generating much debate is that of how to divide up the assets of the provincial government. A proposal on how to divide the income and expenditures of the provincial government has already been sent to the legislature, but has not yet passed its third reading. In the meantime, the central government and local governments are rolling up their sleeves in preparation for a battle over the provincial government's tax revenues.

The Executive Yuan's plan calls for the business tax to revert to the central government, with 40% of the revenues (after the deduction of prize money for the unified invoice lottery) to then be redistributed to city and county governments. The central government will also return 10% each of the commodities tax and the income tax to local governments. The vehicle license tax and the stamp tax will revert directly to city and county governments. The central government will take over cigarette and alcohol tax revenues for itself, redistributing 20% to local governments. It is estimated that the distribution of these revenues to local governments will make them more than 65% self-sufficient.

But city and county governments have made it clear that they are not satisfied with this arrangement.

The heads of the finance departments of the 21 municipal and county governments met in December of last year. They believe that this division of revenues indicates that the downsizing of the provincial government was simply a means of putting all the nation's tax revenues into the hands of the central government.

The TPG's trillions of NT dollars in assets, including land and stocks, plus the income from businesses it owns, are also the focus of much attention. A report in the December 1998 edition of CommonWealth magazine stated that the TPG's debts were equal to only 15% of its assets, which, if it were a company, would make it a very strong company indeed. "If the TPG were a privately held company, people would be lining up in the dead of the night to get a piece of it," says Liu Teng-cheng, acting commissioner of the Department of Finance. In fact, with the articles on the downsizing of the TPG as yet unpassed, the municipal and county governments, as well as the special municipalities of Taipei and Kaohsiung, are all clamoring for lands belonging to the provincial government to be turned over to the local governments of the areas in which they are located.

It seems that downsizing only marks the beginning of the struggle for money and power.

The some 129,000 provincial government employees constitute one huge group of civil servants. After provincial government downsizing, some of them will retire and some of them will be gradually absorbed by government agencies. The photo shows the opening of a fair and friendship games for provincial employees in 1998.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)