Pigs in proverbs

Fables in which pigs are imbued with human qualities have always contained revelations and lessons, all over the world from ancient times to the present.

And from these countless curly pig tales collected through the ages, many famous Chinese pig proverbs have been passed down, such as:

"Wolves and pigs run rampant." This describes evildoers who run about uncontrolled and wreak havoc wherever they go. Shang Shih Tzu of the Ching Dynasty wrote in his book Su Chou, "Dogs and rats rob in Yingchou County; wolves and pigs run rampant and violate the law."

"Boars charge with boar bravery." This proverb refers to people who rush forward without fear of death. The History of the Former Han reports, "The Huns frequently invaded, spreading terror. King Wang Mang conscripted prisoners and slaves from all over China, and gave them the appellation 'Boars charging with boar bravery.'"

"Lower than pigs and dogs" is a malediction applied to individuals lacking in virtue. It can also refer to extremely bad living conditions. A passage from the Legalist classic Shun Tzu reads, "He appears to be human, but is actually lower than pigs and dogs." Chapter 70 of Northern Warlords in the Early Years of the Republic of China quotes, "You're the Prime Minister, and you scheme to make yourself regent. You're really lower than pigs and dogs!"

Many of the literati have bad impressions of pigs, and poets and artists seldom treat them in their works. The Categorical Dictionary of Scenery and Objects in Ancient Poetry compiled by Chu Chung-yuen includes quite a lot of poems about dogs, horses, cows and sheep. But the category of pigs has only two poems. The first one reads:

Pigs seek sties and chickens, coops, In the misty gloaming.

Autumnal trees sway, Revealing Nan Mountain's vague silhouette.

This poem, "View from Halfway up the Mountain" by Wang An-shih, vividly captures the scenery of dusk. The sun sets upon a vast expanse of gray fog. Pigs are returning to their sties, and chickens hop into their coops. The twilight endows a romantic touch to life in the mountains.

A black goat gouges through the fence; A spotted pig crashes the gate.

Fan Cheng-ta's poem "On the Way to Hengyang" depicts life on the farm. A goat uses its horns to break out of the yard, and a pig pushes open the gate of his pen, running outside to frolic. The mischief and liveliness of animal natures was cap tured herein.

Another famous pig poem, "Traveling to Shanxi Village" by the Southern Sung poet Lu You goes,

Don't mock the farm family's homemade winter wine.

At harvest they serve their guests chickens and pigs.

I feared I was lost among the endless mountains and rivers, When suddenly the view opened upon a new village.

The villagers gathered, beating drums in celebration, Their attire simple yet rich with tradition.

I wished for the leisure to hereafter enjoy the moon; I could saunter with ease and visit friends at night.

This is a real masterpiece that has been handed down through the ages. Shanxi Village is not in Shanxi Province; it is a small mountain town near Shaoxing, Zhejiang. Lu You paid a visit there, and being completely captivated by the serenity of the terrain, the beauty of the customs, and the abundance of personal warmth, he composed this poem. First he reflected on the tranquil and jolly panorama of the farming village at harvest time. Though their moonshine was not so tasty, their hearts brimmed with hospitality. And as it happened to be harvest time, they had plenty of chickens and plump pigs, which they served up to treat their guests. The people of the village were simple and sincere, warm and friendly.

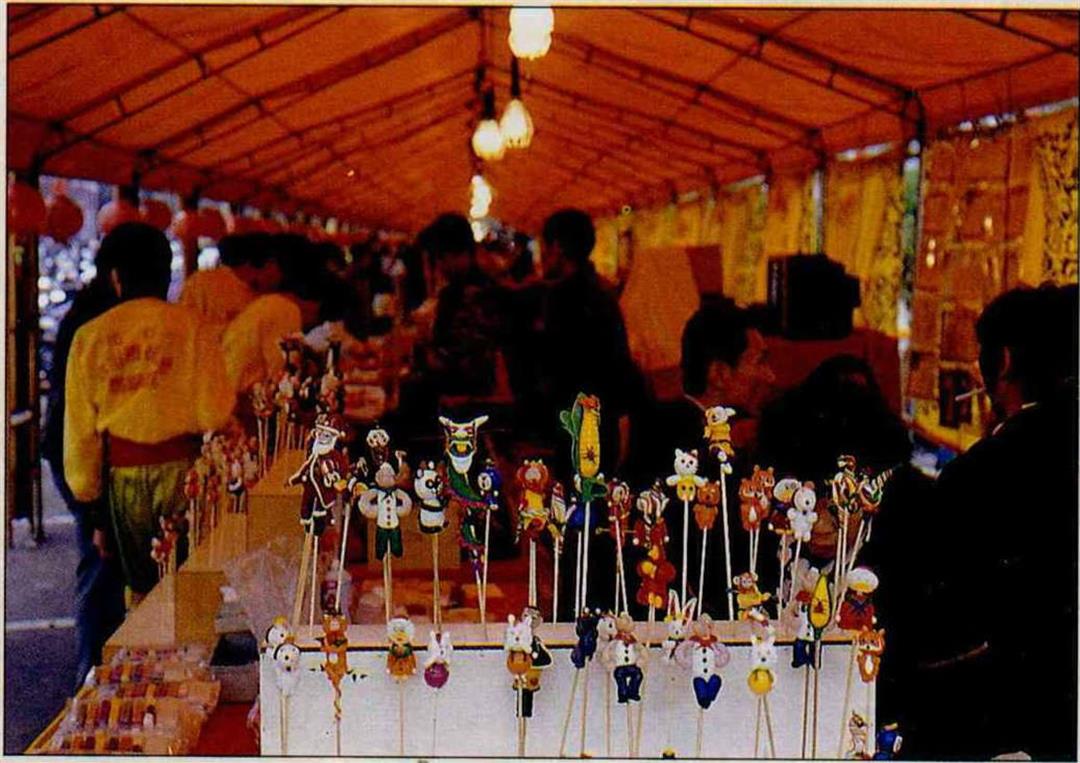

In ancient China marital matches were prohibited between people of certain zodiac sings. One poem enumerated these taboo combinations: "...A snake and a tiger will be severed like a knife; a pig and a monkey will surely fight." In the lower left hand corner, a pig and a monkey can still be seen raising a mighty ruckus. (rephotographed from Chinese Popular Prints)