As the plan has been put into practice, though, a host of holiday malingerers has appeared. We cannot help asking, are the Chinese really "great leisure seekers"? Or are they "hard working toilers"? What exactly is a condition of leisure anyway? Is it the monopoly of the wealthy? Or is it an excuse for hermits? How can you and I achieve it?

"The American is known as the great hustler, as the Chinese is known as a great loafer," according to the great essayist Lin Yutang, writing in 1930s America. As he saw it, the unhappiness of Americans was due to their idolization of the three "vices" of "efficiency, punctuality, and the desire for achievement and success."

Yet this master of humor was also full of hope that "machine culture" would eventually lead to an age of leisure. Humanity would finally tire of uninterrupted progress, material conditions would improve, sickness would be eradicated, poverty reduced, people would live longer, and there would be more food. Lin could not believe that when that time arrived, "man will care to be as busy as he is today."

When can we rest?

The world has indeed progressed. The hasty passing of half a century has seen an improvement in material conditions, people live longer and have more to eat. Yet the most contagious disease of the late twentieth century has become "hard work." Margaret Thatcher, the prime minister of Great Britain in the 1980s, thus constantly worried herself over why it was that if an American made a million dollars, he would think of a way of doubling it; but if a Briton made a million, he would be content with sitting back and enjoying it. It was only when the Iron Lady was removed from office and had the leisure time to visit Taiwan, that she finally discovered how, "All along, this was the heaven of Thatcherism!"

Throughout the 1980s, what American and European scholars saw as the East Asian economic model, resting on the laurels of "Confucian values," was self-confidently developed. Ebullient leaders of the Little Tigers, looking at the economic problems of Europe and America, frequently mocked the "laziness" of Westerners and talked about learning from the mistakes of the welfare state. Triumphant captains of industry openly scorned the slothfulness of Americans.

Into the leisure age?

The 1990s heralded a new era for the hard-working Little Tigers. Regardless of whether they were rich or poor, without a blush people embarked on the massive consumption of automobiles, electronics, kitchenware, furniture, luxury watches, personal attire, leather ware, liquor, porcelain, and even turkey meat and pig offal from the countries of the idle.

As the European and American economies recovered, the East Asian economic bubble burst. Amid sounds of crisis, the policy of making every other Saturday a day of rest began, with business leaders warning about a loss of competitiveness. The consequences have included the members of the cabinet taking a study tour to teach them the art of relaxation, and entrepreneurs adjusting to the new situation by aiming their sights at people's purses. As for the common people, with Confucian virtues of hard work and frugal living still ringing in their ears, they can see that even mainland China has had a five day week for some time. But why is it that as soon as the masses in Taiwan have this extra time and want to use it to go abroad on holiday, the new minister of finance has had to warn them against traveling overseas and letting foreigners make money out of them! Moreover, can anybody really say that the redundancy of tens of millions of mainland workers finally heralds the coming of the Chinese age of leisure?

At this point in time, where should the Chinese turn in their bold quest for leisure?

Hard work without efficiency?

At about the same time as Lin Yutang was writing, another scholar held the view that "Of the nations of the world, it is we Chinese who are most able to put up with hard work." The problem as he saw it, though, was that, "It is also we Chinese whose bodies are most weak and who pay least attention to efficiency." In this view, what Lin Yutang saw as the "vices" of the Americans, became values that the Chinese should try to learn.

The image of the Chinese as hard working, though, is probably easiest to believe for today's middle-aged generation, who came to maturity in the period of the great project of national revival when the values stressed were those of nation-building and recovering the mainland. When they look back, the sweat of the laboring peasants is one thing, but even scholars who did not have the strength to hold a chicken did not have a day of leisure either. Private classes are supposed to have lasted from the break of day until half way through the night-a kind of "self-strengthening" without rest. Pupils could only play when their teacher was having a nap, the only other option being to leave school altogether.

Abolish Sunday!

Then there was the practice of studying late into the night, and spending years without seeing another person. The great political philosopher, Dong Zhongshu, was said to have spent 10 years without going into the garden, while Wei Liangfu spent 10 years writing poems without leaving his chamber. The Yue Lu Academy in Hunan was supposed to have pruned back the cherry trees every year out of fear that the blossoms might disturb the concentration of their students. Success was considered to be passing the exams and entering court life. Even after this, though, one still had to break one's back bowing and scraping, and life remained a matter of self-sacrifice right to the end.

Entering the twentieth century, there were still those who spoke out in favor of abolishing Sunday because they feared that it made people lazy. The great constitutional reformer, Liang Qichao, wrote against wasting time. Watching a film of the Peking opera star Mei Lanfang was cited as an example of disgraceful behavior by the neo-Confucianist Liang Shuming. It is hardly surprising that this should have led to the birth of what the revolutionary writer Lu Xun described as the "sick man of Asia" who "lifts his head but does not dare to look at the world, with a face full of deathly pallor."

From the propaganda of the anti-Japanese war, aimed at strengthening the country and the race, to the schooling that took place after the move to Taiwan, textbooks stressed the morality of scholars who would stay awake by tying their hair to a beam and stabbing their thighs, reading by the glow of fireflies or light reflected from the snow. Naturally, there was no discussion about how bad this might be for the eyesight of the nation's future leaders. Nor was there any suspicion of the Asian family values of the Great Yu, who was praised for being so pre-occupied with fighting floods that he passed his home repeatedly without entering. Needless to say, dying from hard work was never questioned.

Is common pleasure so bad?

If you do not believe these text-book stereotypes, then have a look at Chinese novels: it is equally hard to find a book about true leisure. The heroes in The Water Margin are busy killing the rich and helping the poor, supporting Heaven and following the Way. In the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, they are busy devising strategy and planning how to achieve a balance of power. The pilgrims in Journey to the West hurry to obtain Buddhist scriptures. The bandits and courtesans in the Golden Lotus make love frantically. In the end, it is only in The Dream of the Red Chamber that we find a few young men and women, who will not do anything useful and pass their days dreamily, with no mention being made of them having to busy themselves with anything at all. Daiyu spends her time burying wilting flowers out of sympathy for them, and Qingwen tears up fans. Even the household opera singer spends his time squatting on the ground writing the name of his lover in the sand, with nobody even noticing when it starts to rain. What is the result? Of course, the family is broken up and faces downfall, with not one character coming to a good end or achieving "greatness."

Summing it up, apart from the master humorist Lin Yutang, who spent the years of World War II in America, trying to save the country through his writing, where can the great leisure-seeker of China be found?

"Leisurely Chinese? The paintings are full of them!" says Wang Yao-ting, deputy head of the painting and calligraphy section of the National Palace Museum. You can start to find examples by looking at what the characters in old paintings do in springtime.

Spring leisure

When spring arrives, five or six gentlemen go with their servants to bathe in the river, frolic in the breeze and sing all the way home. Such was the model advocated by Confucius, usually as solemn as a dog at a funeral, and which came to be admired and practiced by generations of literati to follow.

A few cherry blossoms appear and the river begins to warm up. A group of friends with their servants in train travel down the river bank to sit and watch the reeds and the wild ducks, the dancing butterflies, the fish leaping and the boats sailing by. In moments of high spirits they pretend to be fishermen, or they lie down and have a snooze.

Those who do not like the water can take advantage of the blossoming flowers by walking in the mountains, playing stringed instruments, or burning incense in the bamboo groves. Some just sit on a rock gazing at the distant clouds. The company of a good friend, tasting spring water in a pine pavilion, toasting each other on the water-all are fine ways of satisfying the emotions.

The leisured class? The moneyed class!

"Returning late after a spring journey" is obviously a favorite topic in Chinese painting. A servant takes a short rest by putting down his burden of tea, wine and deck chairs. The master on his little mule decides to return home by moonlight. When he arrives, though, he finds there is no response to his knocking on the front door, apart from his servant's snoring reverberating through the heavens.

There are also those who travel in the daytime and just cannot get their fill of the flowers, then arrive home and see that the peach and plum blossoms are just opening in their gardens. Heaven and earth is like an inn that contains all the things of nature. As for time, a hundred generations can pass by as life floats along like a dream. In the deep of night the flowers might be sleeping, but as every minute of spring is to be treasured like gold, why not light some candles and spread some lanterns to illuminate a night-time banquet, and pass the time in their company?

Such elegant and happy emotions are ultimately those of the pursuits of a leisure class who can "relax with nothing to do, wake up with the east window already red, gain self composure from quietly watching nature, and happily pass the time." There is no worry about whether it is night or day, or about the efficient use of time. Such is the epitome of the great leisure seeker who has not yet caught the pernicious habit of success.

You can see from the pictures that such people are always men, that they have servants in train, and that they are able to throw away money with abandon.

In the Ming-dynasty painting Returning Late From a Spring Journey, when the leisurely lord arrives home and finds no response to his knocking, there can also be seen a laborer in the garden carrying a hoe on his way to work. In a Song-dynasty painting, while the leisure seekers are crossing the water by boat in the deep of night, absorbed in appreciating the moon on the water, they can also hear the sound of a distant fisherman tapping to attract the fish.

Leisure need not mean spending money

"Compared to ostentatious luxuries, leisure involves the least expenditure, and it is not the monopoly of males," says Tseng Chao-shu, professor of Chinese at the National Central University. In the literary sketchbooks of the Ming and Qing dynasties that talk most about spiritual tranquillity, you can in fact see that there are many women who have the best understanding of how to arrange a life of leisure. The character Yunniang, in the Six Books of a Floating Life, is an example.

Called by Lin Yutang "the most beautiful woman in Chinese literature," she lives with her poor husband in straightened circumstances, "embroidering while he paints, and fulfilling the demands of poetry and wine by happily spending her life making clothes and cooking." She uses her skillful hands and kind heart to arrange a life for her husband that is the envy of later generations.

Because of the difficult conditions, Yunniang has to devise ingenious methods for making and repairing clothes and to brighten up the house. On summer days she fishes with her husband under the shade of the willow, and the couple walk up the mountainside to view the sunset, reciting couplets as they go. In the evening, with the sounds of the insects on all sides, they drink under the moon and eat with a mood of slight intoxication.

When the lotus flowers begin to blossom, closing in the evening and opening in the morning, Yunniang even places a bag with a few tea leaves inside a cupole, retrieving it the next day so as to make fragrant tea with spring water. Borrowing from the flowers in this way does not require any expenditure, but putting so much effort into making two cups of tea must surely be indicative of the great leisure seeker!

The rough road to leisure

It could be said that putting aside extravagant ways and the seeking of power makes a life of leisure cheaper and simpler than that of more ostentatious modes of passing the years. But achieving this is not just a matter of having enough time. It also depends on having what the Qing-dynasty scholar Jin Shengtan called "an extra ability of the heart, and an extra pair of eyes." It is only when one is in possession of these special qualities that one can be like Yunniang and manage the frugal life of the artist.

Alternatively, one could be like the Qianlong emperor, who used the treasury of the world's most powerful nation throughout the 18th century to build palaces and gardens and to accumulate the treasures of the world. As well as being involved in the machinations of everyday life and in leading military expeditions, he also spent his leisure time writing poems on, and stamping his seal on, just about every work of art available. Among these there are even some poems about fishermen, wood-cutters and hermits. In the end, though, he just left a reputation for being somewhat pretentious.

To truly achieve the "busy life of the leisured" and the "leisure of the world of the busy" may also require going through some pretty arduous experiences. The most talented and enthusiastic of intellectuals tend to start out by wanting to serve their country and do great things. Yet for the great poets Liu Zongyuan and Su Dongpo, it was only after they had suffered the intrigue and lying of court life, and repeated setbacks in their careers, arriving at the disappointment of middle age, that they were able to understand the simple pleasures of nature.

After treading such a rough road, one becomes tempered in ways that enable one to rest just about anywhere.

Hard work and lasting tranquillity

Of course there is also the bold, overflowing enthusiasm of youth, which feels at odds with the world of officialdom, leading to resignation from official life in favor of burning all bridges and returning to nature. The writer Chen Hsing-hui, who has compiled songs of the country garden down the dynasties, takes Tao Yuanming, the first poet of this genre in the history of literature, as her favorite master of leisure.

In an age when, as Tao saw it, the court gentleman lived a life of shameless wealth and competition, he refused to kowtow to insignificant non-entities just for the sake of collecting his salary. Although he had a garden he could return to, he was not well off and could not even grow enough for his own needs. Of course, what people tend to remember about Tao is the grand spirit of his famous verse, "Picking chrysanthemum under the eastern fence, I gaze on the southern mountains with tranquillity." It is easy to forget that he also spilled a lot of ink describing just how difficult his living conditions had become.

Appreciating the river breeze and the moon over the mountains is one thing. Knowing about the cock crowing and the evening dew soaking your clothes is another thing altogether. When Tao Yuanming went back to the garden and began his life in the wilderness, he was beset by worries that the frost would damage the crops and that the weeds would flourish while the vegetables would be thin.

Although life was hard, Tao nevertheless soon turned from being an ensnared and inhibited official who felt at odds with court life, into a sincere, rustic character who could "make greetings when he passed someone's door, and tirelessly laugh and talk."

Tao's most famous character, "Mr. Five Willows," who "works excessively hard, but has leisure in his heart," is a testimony to true leisure. Leisure not only requires having the time and the high spirits to enjoy walking in the spring mountains and sailing the moonlit rivers. Even more important is to be at peace with one's inner self and to have the freedom that arises from complete self-possession.

Peasants do not enjoy nature?

Tao Yuanming, though, was from a good family and well-read before he came to the life of planting when the weather is clear and reading when it rains, and perusing the classics after a spate of hard labor. Generations of hermits who followed his example would "try to finish reading Tao in bed, then get up to hoe melons when the rain is light." A vision still very much the reserve of the literati.

By the time of the professional leisure seekers who seem to have been mass-produced in the Ming and Qing dynasties, it could be effortlessly announced that "wood gatherers and shepherds are interested in the wilds but do not know how to appreciate them," and "farmers and gardeners retreat to the mountains and forests but do not know how to enjoy them."

Another Qing-dynasty leisure seeker, Zheng Banqiao, took a coldly satirical view of this. Only achieving the lowest grade of officialdom when he was 50, he was of the opinion that the farmer was "the first grade person between heaven and earth." The gentleman, on the other hand, was the lowest of the four classes of people, and special contempt was reserved for the literati.

Zheng could not stand official life in the end and resigned to spend his time painting, an activity that he saw was "to comfort the toilers of the world, not those who live in peace and comfort." In his thinking, the peasants have no month of rest and the life of the fields is one of exhausting hard labor. Yet he also saw the pleasure of rural life, when the peasants have finished work and "the children who were picking melons laugh and wash their feet at the water's edge as the sun goes down, telling outrageous stories before the evening wind picks up." This was a simple kind of leisure that the sophisticated literati were unable to appreciate.

After the division of work and leisure . . .

Discussing Chinese feelings about leisure, former deputy head of the National Palace Museum, Li Lin-tsan, takes the Song-dynasty painting Leisure and Work, by Ma Hezhi, as an example. With weathered face and tattered clothes, a fisherman sits under a tree on the bank of a river concentrating on making a pair of grass sandals. He uses both hands and feet in the enterprise, his veins stand out, yet he still comes over as being relaxed in mind and body, blending into the surroundings to create a tranquil scene. It is interesting to contrast this image with that of the master strategist Zhuge Liang, from the novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, who sits on the top of the wall of a deserted city as an enemy army approaches, holding a feather fan and wearing a soft hat, playing chess and laughing. Which one is the most leisured?

Does the peasant really not know what is interesting? Is the happiness of the fisherman and the wood gatherer naive? Is that of the hermit contrived? Outsiders probably find it hard to tell. The best judge of one's feelings, of course, is always oneself. An interesting distinction between the life of the peasant and that of the hermit, though, is given by Lin Ku-fang, an ethnomusicologist, who says that, "When you are planting the fields you are a peasant, when you are sitting back, looking at the mountains, you are a hermit."

For Lin, it is in peasant society that people follow the rhythm of working when the sun rises and resting when it sets. No matter what the weather is like, everything the peasants do is determined by the seasons and the life of plants and animals. When the work is finished, the peasants will usually sit under a big tree to gossip and play music, relaxing in a natural way.

A bigger problem arises when modern "machine society" becomes too far removed from this natural rhythm. "Modern life is divided into work and leisure and looks at things on the basis of efficiency," says Lin, stressing that "Talking about efficiency in relationship to work can be most inefficient when it comes to life as a whole."

The cog's dream of leisure

In an urban environment, finding a true enjoyer of leisure, even wanting to become one within the framework of having every other Saturday free, can be a grueling test.

The modern division of labor means that when at work, according to the rhythm of the boss, "people" are reduced to personnel, roles, symbols, alienated cogs in the machine, achievement charts, productivity, daily clocking in and quantification.

When it is time to finish work or have a day off, the tension is relaxed somewhat, but this is not necessarily "leisure." Instead, we busily eat, drink and sleep, to recover our energy; we also continue to make our contribution to the economy by consuming. When we go back to work, we remain good little cogs, persisting in striving and "going just that little bit further" for the boss and for the country.

"Increasing leisure time is actually a good opportunity for one to recover one's own self," observes Professor Tseng Chao-hsu. Leisure time can be used to restore our shattered selves by following the rhythm of nature, fixing our own timetable, and getting back a feeling of freedom. After doing business, you can play Chinese checkers. After practicing medicine, you can stay up all night researching the history of military strategy. After working in the day, you can use your leisure time to collect together the things you are really interested in and happily make them your life. It is at this time that you become a great enjoyer of leisure.

Leisure in haste and haste in leisure

Lin Ku-fang divides leisure into three stages. The first is "resting," when you do not do anything, but most importantly you must not stifle your self by creating "leisure pressure." Next comes "filling in the gaps," which involves doing things that you would not usually do, such as walking in the mountains. Walk until you work up a sweat, get tired, rest, then set off again. As you become completely relaxed, you become aware of your body and the relationship between nature and life. The final stage is "observing," when you are able to properly reflect on your existence, face the past and the future, and achieve a completely natural state whilst also being in control of your mind.

When you return to work, one possible attitude to adopt is that of "letting the sheep out to pasture, then rushing to herd them and count them in case they get lost," says Lin. "Another one is to herd them together and count them while leisurely singing a mountain song."

In other words, being "busy" is when you pursue somebody else's objective. "Leisure" is when you peacefully confirm your own freedom. It seems that, when faced with Saturday off, we can either exhaustively follow the itinerary arranged by a travel agent, sleeping on a bus and getting off to visit the WC, or we can resolve to go and do many things in a relaxed manner.

Professor Huang Yung-wu, who delves into the past and the present when talking about the "aesthetics of living," also thinks that "those who seek leisure in this world are few, while those who seek hardship are many." He says that once somebody asked the Zen master Zhi Xuan the question, "In the human world, it is always a case of being very busy and having little leisure. What is to be done?" Zhi Xuan's answer was, "If you handle things well, then you can be busy in a leisurely way; If you handle things badly, you can still be rushed in times of leisure."

God rested for one day, we have two

The basic distinction between being busy and being relaxed lies in not allowing your heart to be at the beck and call of circumstances. Does this, then, mean that we definitely need every other Saturday off if we are to achieve the full psychological conditions of leisure? Even God spent six days creating the world, with only one day off for rest.

Perhaps somebody who has gone beyond this question is an English gardener who was once interviewed by Sinorama. Charging like a bull into his office at 8 a.m. as arranged, he explained in a slightly embarrassed fashion, "I was here half an hour early so that I could go to the green house and inspect the seeds I planted yesterday. Then I thought I may as well do some watering. . . ." Finally, he added, "In the end I just had to run back here."

This bearded, middle-aged gardener, with his hands still muddy, was actually responsible for a team of workers maintaining the scenery of a landscape garden of 10 acres. While introducing the flourishing plants and emerald lawns of his kingdom, he would leap forwards now and then to pluck a weed from a border, much like an editor spotting a glitch in a text.

On being asked what he would do if he won the lottery, he answered, without a second thought, that he would restore a piece of land in the west of the garden to its original 18th-century appearance. If he could do more, there were a lot of lawns that were still in need of edging boards.

Does a gardener ever get tired of his job? He answered this question with one of his own, "Can he?" Then he continued, with an unforgettable smile, "Up till now, I cannot remember a morning when I have woken up and wished that today was a holiday. . . ."

Truly a great enjoyer of leisure! Moreover, one who also has the desire to be on time, be efficient, and be successful.

The master is sweeping

It could be said that history's great leisure-seeking philosophers disappeared a long time ago, along with our models. Singing as you let the sheep out to graze and working your art with the garden plants are not commonplace activities in modern society, with its division of labor. The common cog spends its day in alienated labor and consuming material goods according to the cycle of the economy, always busy at both work and leisure, and in a state of constant exhaustion.

Is there a solution to this problem? Ho Sheng-chin, is the head of the Pine Garden in the Yangming Mountains, which consists of a mountain stream and valley. Yet he has to worry about the extra day off because cars are no longer allowed to enter the area, resulting in a drastic reduction in customers. Designing and running such a garden involves a lot of effort and worry.

"When I am tired I just do some sweeping," he says. Taking a brush he thoroughly sweeps the garden from top to bottom. Without raising the dust, he piles the dirt and does not damage the broom. Sweeping until you sweat and come to forget yourself is not tiring.

"It is my 'self' that is tired. When I forget my 'self' then my heart is at 'rest'!" he says.

In modern society, you just never know when you might come across somebody who is really able to enjoy true leisure.

p.18

Resting under an old tree outside a temple (above) and a painting by the talented Ming artist Tang Yin bearing the stamp of the Qianlong emperor (below, courtesy of National Palace Museum). Confucius said that those who sleep in the daytime are like rotten wood that cannot be carved, but loafers past and present just love to loaf.

p.20

A scene outside the National Palace Museum (left). Returning Late from a Spring Journey by the Ming-dynasty artist Dai Jin (right, courtesy of National Palace Museum). Wearing scanty spring clothes, bathing in the mountains, and enjoying the breeze were Confucius's idea of a good time, and were happily put into practice by later generations.

p.22

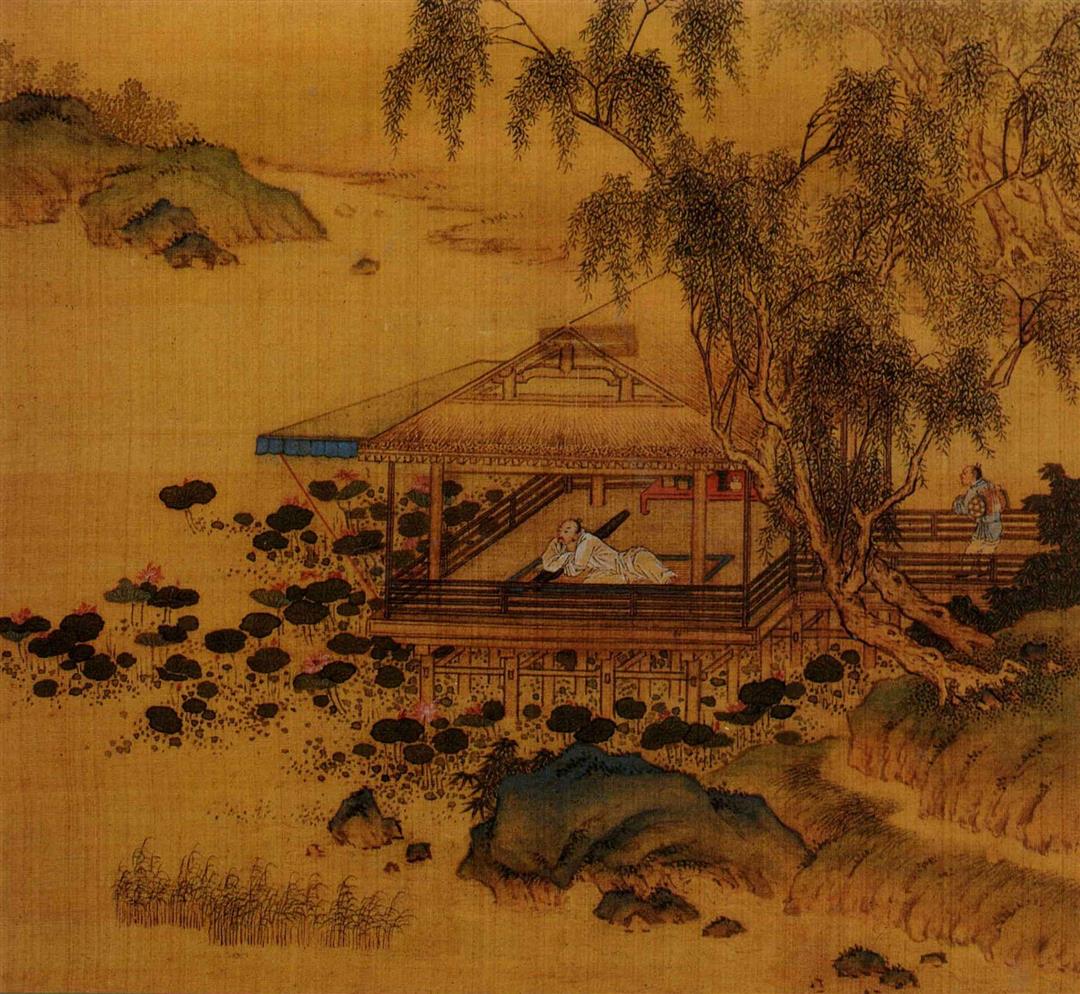

The ancient gentleman could not adjust his mood without music. A Ming-dynasty character

reclines with his zither in his arms (right, courtesy of National Palace Museum). Modern-day literatus Professor Chang Ching-chih thinks that true relaxation is more than just having a few days off (left).

p.24

Evening Banquet with Blossoms by the Qing-dynasty artist Leng Mei (right, courtesy of National Palace Museum). A homely scene in Taiwan (left). Life floats along like a dream. How many happy times can you have? Spring days are short, so treasure the blossoms while they last.

p.26

A leisure seeker in this Song-dynasty painting enjoys the moon and the blossoms while a fisherman taps to attract fish in the near distance (courtesy of National Palace Museum).

p.28

When you are working you are a peasant, and when you sit back and look at the mountains you are a hermit. A farmer brings his calf back under the shade of a willow (left, courtesy of National Palace Museum). The body of the farmer with a mobile phone is busy, but his mind may be at rest (right).

p.30

Pine Garden owner Ho Sheng-chin uses sweeping up as a way to clear away his own problems. Unfortunately it is hard to find a pure leisure seeker in this material world. (background painting courtesy of National Palace Museum)

A scene outside the National Palace Museum (left). Returning Late from a Spring Journey by the Ming-dynasty artist Dai Jin (right, courtesy of National Palace Museum). Wearing scanty spring clothes, bathing in the mountains, and enjoying the breeze were Confucius's idea of a good time, and were happily put into practice by later generations.

The ancient gentleman could not adjust his mood without music. A Ming-dynasty character reclines with his zither in his arms (right, courtesy of National Palace Museum). Modern-day literatus Professor Chang Ching-chih thinks that true relaxation is more than just having a few days off (left).

The ancient gentleman could not adjust his mood without music. A Ming-dynasty character reclines with his zither in his arms (right, courtesy of National Palace Museum). Modern-day literatus Professor Chang Ching-chih thinks that true relaxation is more than just having a few days off (left).

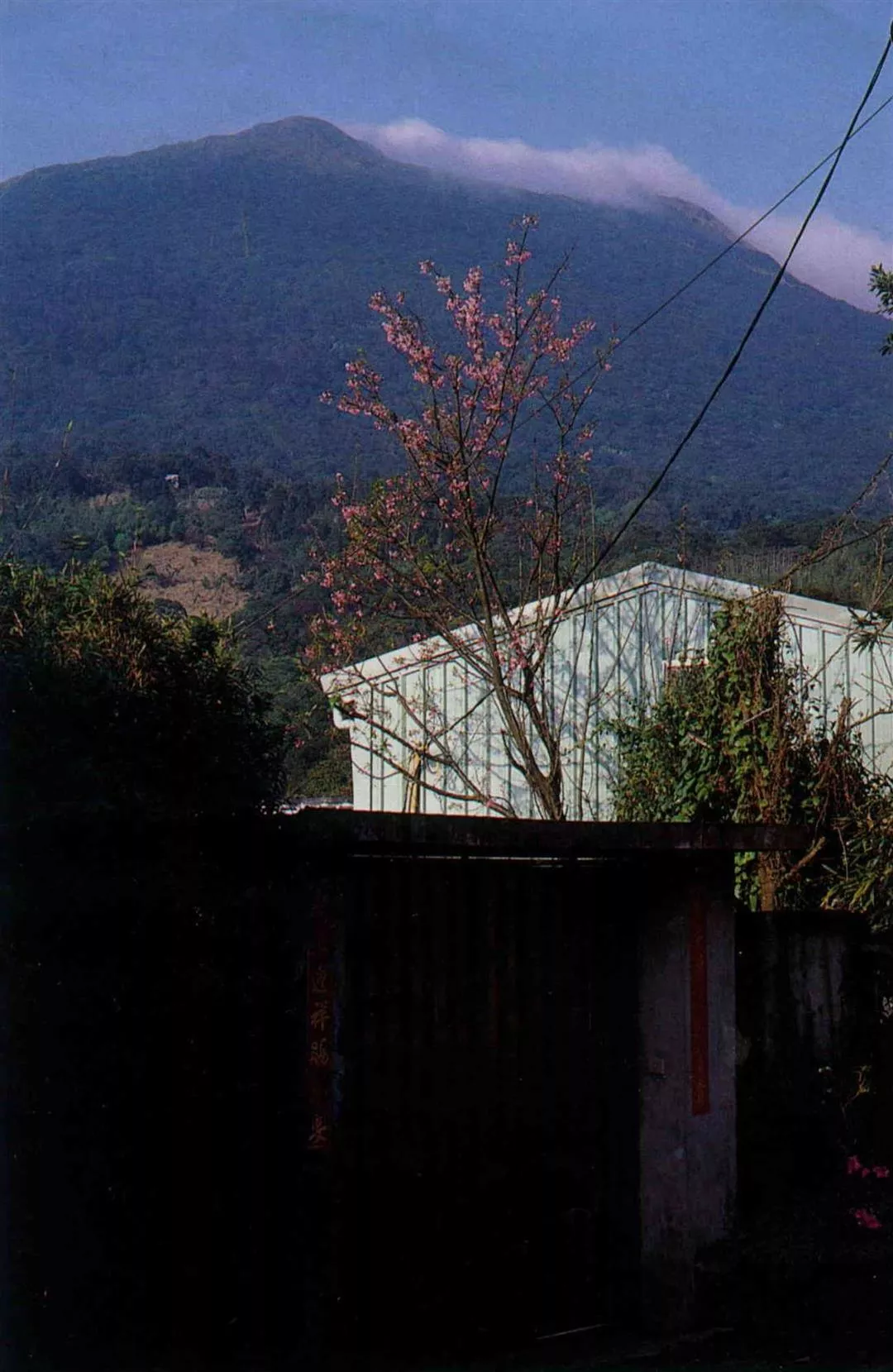

Evening Banquet with Blossoms by the Qing-dynasty artist Leng Mei (right, courtesy of National Palace Museum). A homely scene in Taiwan (left). Life floats along like a dream. How many happy times can you have? Spring days are short, so treasure the blossoms while they last.

Evening Banquet with Blossoms by the Qing-dynasty artist Leng Mei (right, courtesy of National Palace Museum). A homely scene in Taiwan (left). Life floats along like a dream. How many happy times can you have? Spring days are short, so treasure the blossoms while they last.

A leisure seeker in this Song-dynasty painting enjoys the moon and the blossoms while a fisherman taps to attract fish in the near distance (courtesy of National Palace Museum).

When you are working you are a peasant, and when you sit back and look at the mountains you are a hermit. A farmer brings his calf back under the shade of a willow (left, courtesy of National Palace Museum). The body of the farmer with a mobile phone is busy, but his mind may be at rest (right).

When you are working you are a peasant, and when you sit back and look at the mountains you are a hermit. A farmer brings his calf back under the shade of a willow (left, courtesy of National Palace Museum). The body of the farmer with a mobile phone is busy, but his mind may be at rest (right).

Pine Garden owner Ho Sheng-chin uses sweeping up as a way to clear away his own problems. Unfortunately it is hard to find a pure leisure seeker in this material world. (background painting courtesy of National Palace Museum)