A Tokyo love story

Tien Chun-chou was born in 1943 in Hsiulin, Hualien. Her father was the first Truku Christian convert and her mother was a midwife. Tien's childhood years were spent with her grandmother going into the mountains to plant sweet potatoes and corn and with her uncle hunting in the mountain forests. Once when she was in sixth grade her mother went away for training and Chun-chou took her place helping women in the tribe give birth. She had absolutely no fear of the bloody scene that came with the territory.

After graduating from middle school Tien Chou-chu entered National Taichung Nursing College and became a full-fledged midwife. In 1977 she brought an end to her first marriage and with a friend went to Tokyo to pursue beautician studies. Once in the process of asking for directions, she got to know her current husband, Tadao Maruyama and a romantic "Tokyo love story" unfolded.

The beautician course wound up in a short three months and after Tien had returned to Taiwan, like the affectionate "Momotaro" of Japanese folklore Maruyama braved all hardships and visited her four times, finally taking her back to Japan to marry after winning her hand. To while away the lonely hours in a foreign land, Tien Chun-chu studied handicrafts in Japan and earned many teaching certificates as a puppet maker. She was planning to return to Taiwan and teach the craft but now her four large iron chests filled with specialized books sit quietly on the back balcony of her Hualien home.

Leafing through a neatly bound volume of photocopies of "land waivers" at Tien Chun-chou's home, one can begin a discussion of the Hsiulin movement to regain their land with the regulations governing "mountain reservations" (later termed "Aboriginal reservations") issued by the government in 1968. At that time the National Government carved out 260,000 hectares of mountainous land as a reservation area. The Aborigines had land use and cultivation rights to this area but they had to cultivate the land for ten years (now changed to five years) before they could get ownership of the land.

Yet the regulations clearly stipulated that these reservation areas could not be transferred or leased to Han Chinese but only to Aboriginals. But during that era when economic development was worshiped above all else, a convenient "exception" was included in the regulations. Han Chinese could, in fact, lease and develop the land if it were for the purpose of mining, quarrying, or sightseeing or for industrial resources and did not hinder national security.

In 1973 the Asia Cement Corporation was attracted by Hsiulin's rich mineral resources and decided to set up a factory there. They also held a public meeting in Fushih Village in Hsiulin to explain the leasing arrangements. They made a commitment to the townspeople of a nine-year lease and issued compensation payments of NT$3,000 per landowner for crops and buildings on the land. But the landowners didn't know that according to the Mining Act Asia Cement could, if it wanted to, lease the land in perpetuity regardless of whether the landowners agreed or not. Neither did they know why Asia Cement the next year obtained the letters from all of them waiving their land rights.

Chang Jung-wen, now deceased but then mayor of Hsiulin and a key player in these events, once said, "All this is something the Aboriginals agreed to." The problem is, can it really be that "over 100 landowners gave up the rights to a total of 270 parcels of land all given up on one and the same day?" Chung Pao-chu, who has done a great deal of research on the cement industry's major thrust into Hualien and Taitung cannot but help shake her head. There are obviously too many question marks in this whole story. And what you can see in the whole process is that to facilitate Asia Cement obtaining the lease and getting the landowners to give up their land rights, the township office actually played a behind-the-scenes role to push things along.

As for Asia Cement, they stress that everything was entirely legal. The company had the lease and the land waivers. Not only did the company in the very beginning give compensation to the landowners, for many years it has been giving the township office a yearly rent of over NT$15 million, and it has received an "Award for Excellence in Providing Aboriginal Employment" for the benefits it has brought to the local community. As it now faces Aboriginal requests to return the land, Asia Cement is hoping the government will solve this problem as quickly as possible.

Of all the Aboriginal townships in Taiwan, Hsiulin's loss of land is one of the worst of all. Researchers have pointed out that alcoholism and child prostitution among Aboriginals in Hsiulin are especially serious problems. This is related to the Truku's loss of land and the breakdown of their social structure.

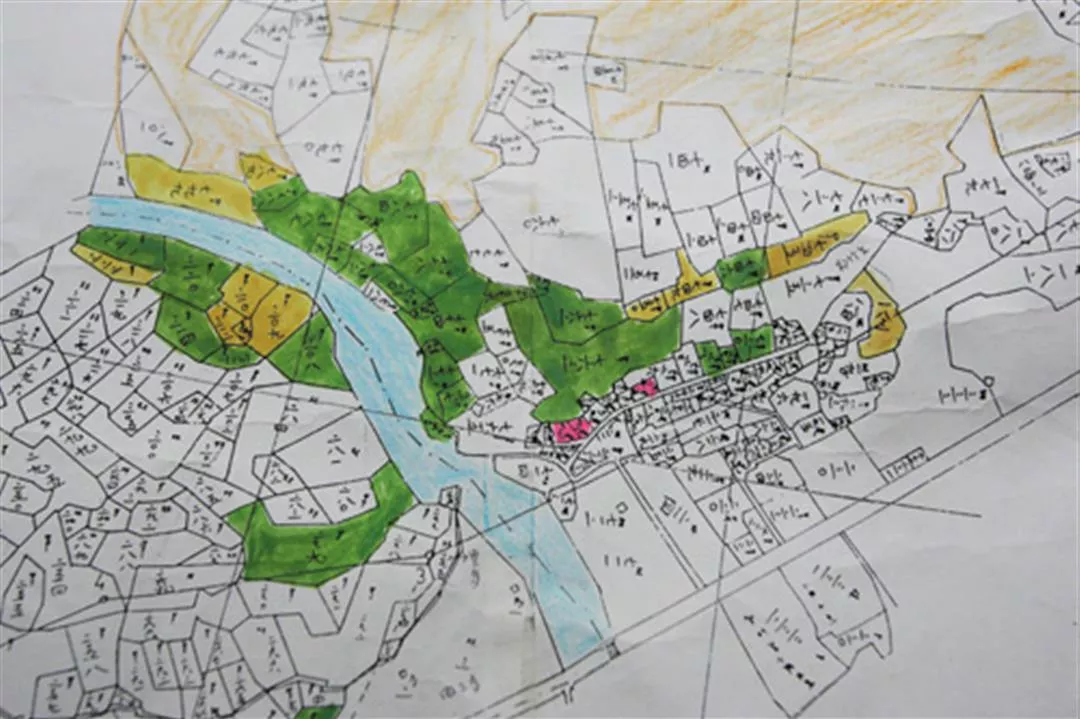

The green patch in the picture is the land under dispute between the Truku of Hsiulin and the Asia Cement Corporation.