The 10 aboriginal tribes in Taiwan are mostly to be found in remote mountain areas, and have traditionally earned a living from hunting and farming. Since they have clung to their own life-styles and religious beliefs, they have always been regarded as something of a mystery.

Recently, however, the aborigines have benefited from government efforts to improve transportation and living standards in mountain areas, and some have even moved down to live in the plains. Despite this modernization, most tribes have preserved their ancient sacrificial ceremonies. The annual harvest ritual of the Tsao tribe and the sacrificial ceremony of the Saisiat tribe in honor of the pygmies (short people, as the aborigines call them), are perhaps the most representative.

The Saisiat aborigines hold a sacrificial ceremony in the autumn every two years, and a grand ceremony every 10 years. In the past, outsiders were not allowed to attend these ceremonies, but recently, the ban was lifted as the aborigines became more open- minded. All the ceremonies draw crowds of ethnologists, journalists and tourists, to watch, conduct research and report on the activities.

In mid-December last year, the sacrificial ceremonies held at Nan-chuang in Miaoli County and Wufeng in Hsinchu County drew a crowd of tens of thousands of tourists and aborigines returning from the plains area. Numbering 3,000 altogether, the Saisiat aborigines are believed to have emigrated to Taiwan from the Malay peninsula in about the 4th century A.D., and settled down in northern Taiwan.

The ceremony at Nanchuang was held at Hsiantien Hu (Facing Heaven Lake) some 1,500 meters above sea level. As access roads to the place are more difficult to negotiate than those leading to Wufeng, the ceremony has been preserved in a form more close to the original.

Origins: It is believed that the sacrificial ceremony took root some 500 years ago, when the Saisiat lived side-by-side with a negrito pygmy tribe known as "spartai," who taught them the arts of farming, weaving and building.

Though grateful for these gifts, the Saisiat were enraged over the pygmies' habit of raping their women. One day when a youth discovered that his sister had been raped, he booby-trapped the bridge which connected the two tribal lands. That night, as the pygmies went to attend the harvest festival held in the Saisiat domain, the bridge collapsed, and they all fell into a deep abyss. When the only two survivors complained to the Saisiats, the youth admitted his responsibility, but explained he was driven to do it because he could no longer bear the insults of the pygmies. In an expression of regret, the pygmies taught the Saisiat all they knew, and then walked away to the east, never to be seen again.

To show their appreciation of this gesture, and to ward off retaliation, the Saisiat tribesmen held a sacrificial ceremony after the harvest, and the custom has been passed down from generation to generation, as a symbol of the ethic of honoring the dead.

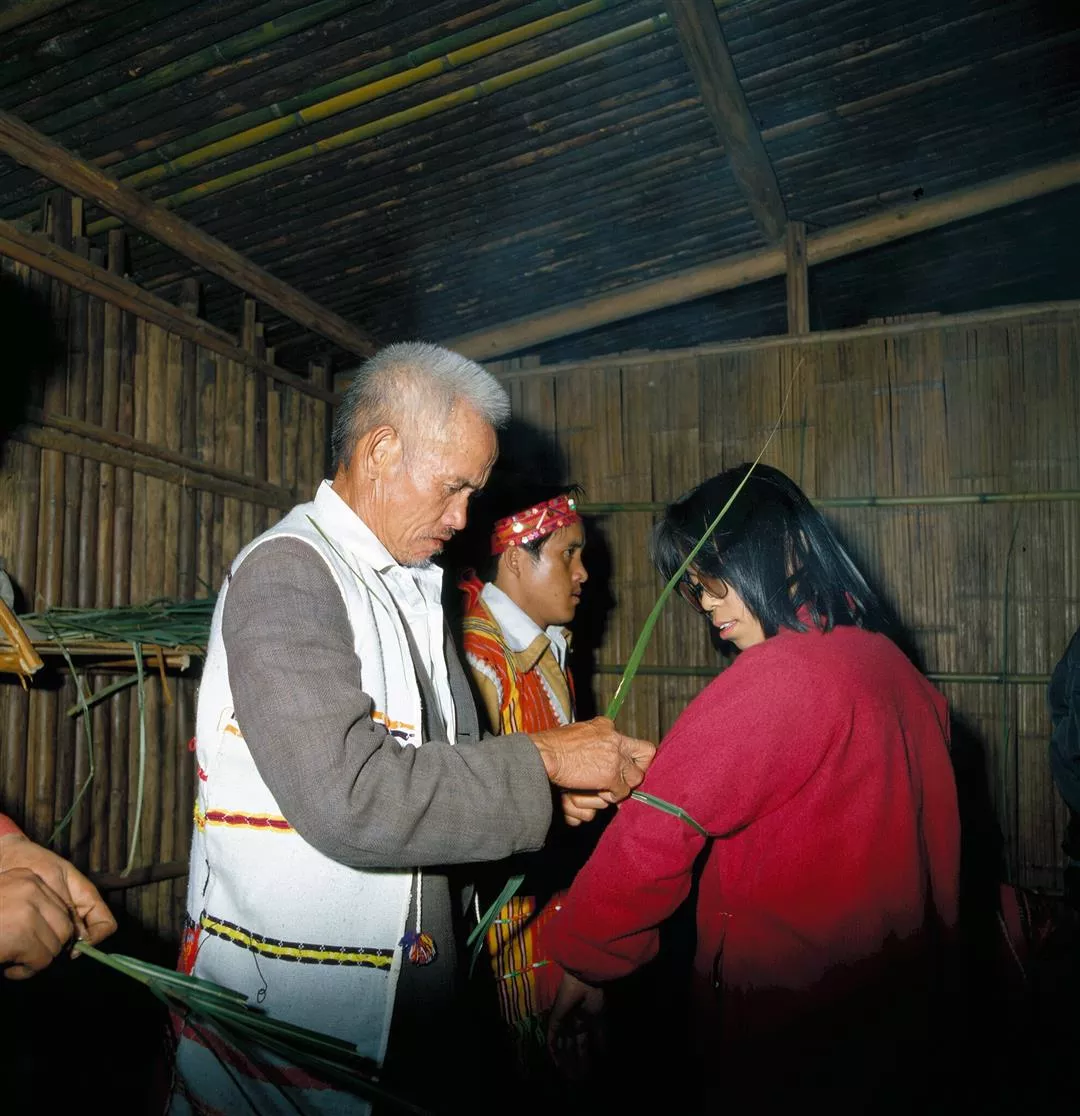

The ceremony: Before the ceremony begins, the elders of each tribe convene to decide on the most auspicious date and the organizational details. Pickets are assigned to prevent outsiders from annoying the spirits of the pygmies. The Saisiat believe that tying a blade of grass round their bodies will ensure security for the family, so they urge tourists to do the same.

The ceremony also provides a good opportunity for all the tribes men to learn of happenings over the past two years. Inter-tribal conflicts are solved by the elders of two families, the Chu and Feng.

When all preparations have been made, the representatives of the Chu family arrive first at the worshipping area. They face the east as they invite all the pygmies to attend the sacrificial ceremony, and pray for good weather and smooth proceedings. Then they start an all night-long dance to the accompaniment of songs to invoke the spirits.

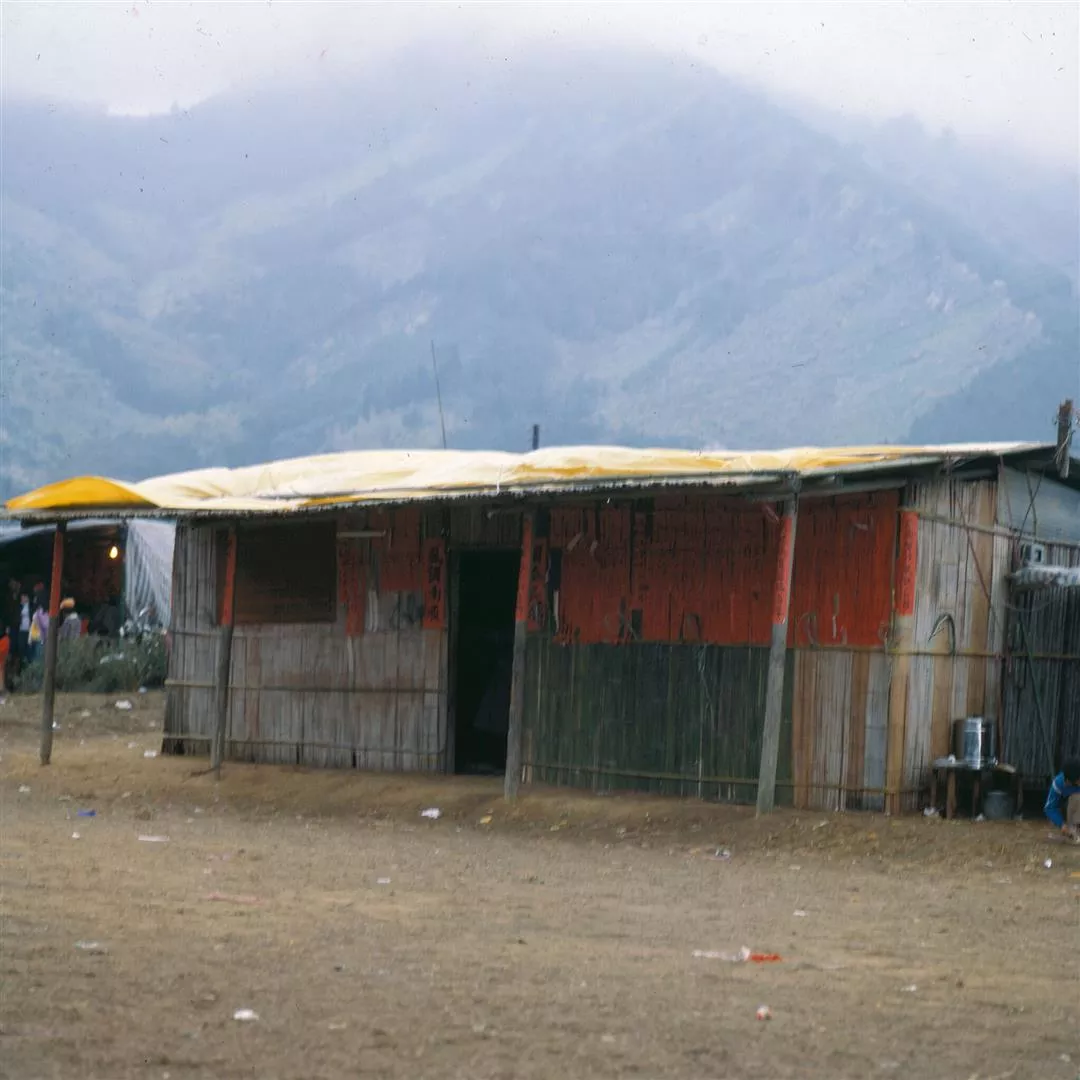

The daughters-in-law of the Chu family make rice cakes to encourage the descent of the "spartai" god. Only members of the Chu clan are allowed to attend this ceremony. Except for the spirit house, there are no altars or tablets in the worshipping area.

As night falls, all the tribesmen put on traditional garments to dance to the rhythm of sacrificial songs, and the tinkle of bells under the leadership of the dancehat bearer. Tourists are invited to join in this dance.

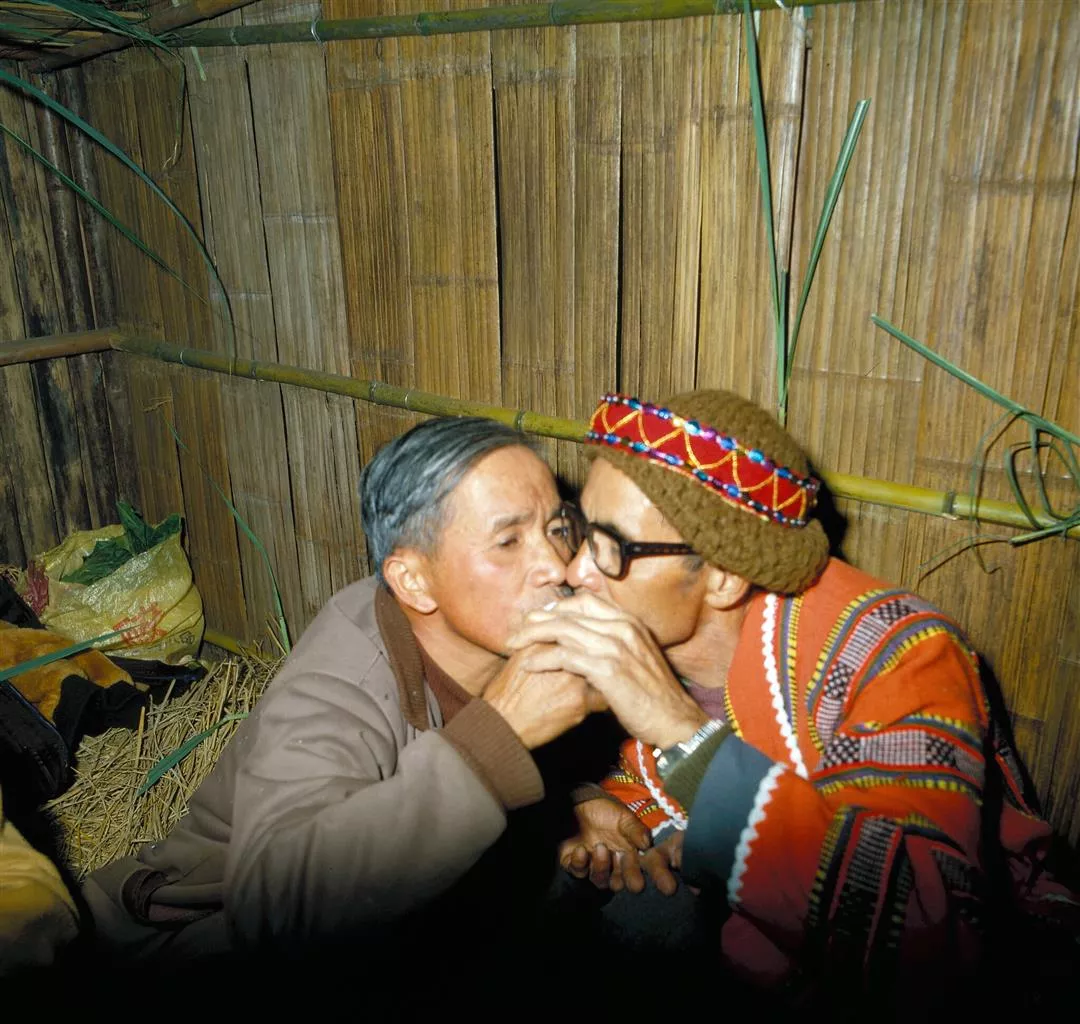

At midnight, the dance is temporarily suspended, and all the men stand facing the east. The member of the Chu family who officiates at the ceremony stands on a mortar, and those taking part in the circular dance procession leave an opening for him to usher in the pygmy spirits. Afterwards, the tribesmen share the homemade rice wine with everyone present, and the dancing continues until daybreak.

The ceremony reaches a climax on the fourth night when the tribes men begin their program of entertaining the pygmy spirit. A striking feature of the four-night dance celebration is the shuttling of several young men bearing a huge dancehat on their shoulders. Embroidered with glittering metal and colorful paper, each dance-hat is inscribed with the surname of a family and inlaid with a small mirror to represent the sun rising in the east.

Another feature is the sacrificial songs, which are changed each night. To the amazement of ethnic- musicians, the 30-odd songs have perfect rhymes, and are sung in chorus with a male voice echoed by the female singers. Before the ceremony starts, the elders teach the young people to sing these songs.

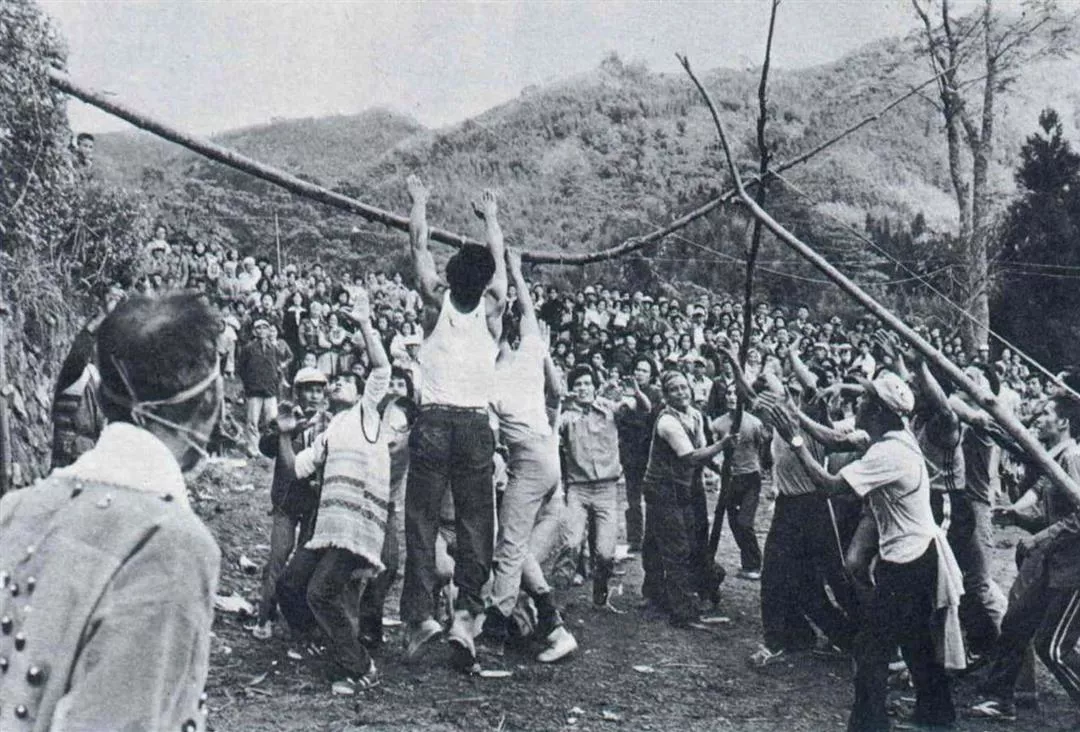

At 6 a.m. on the fifth day, the aborigines begin to exorcise the pygmies' spirits. Members of the Chu family place a hazel tree over the spirit-house, and tie straw around it. The youths jump up to grab at it, and break up the hazel tree and throw the pieces toward the east to symbolize the exorcism of the evil spirits. In the final ceremony, the young men put on an awesome aspect to impress the pygmies.

When the one-week ceremony and three weeks of preparation end, serenity returns to Hsiantien Hu as the aborigines return to their homes and jobs.

[Picture Caption]

1. During the sacrificial ceremony, aborigines of the Saisiat tribe wear traditional bells on their backs to beat out the rhythm. 2. Hikers on their way to the Hsiantien Hu. 3. A Saisiat tribesman ties a blade of grass round the arm of a tourist to ward off evil spirits. 4. Sharing a goblet of wine is the tribesmen's way of showing friendship.

All the aborigines who have settled down in the plains area must return to their homes to honor the dead. Even after dancing all night, they are not tired.

The spirit house has no tablets honoring the gods, and only serves as an activity center during the sacrificial ceremony. A group of young men shoulders the gaudily decorated dance hat. The bells on the hat also beat out the dance rhythm. In the ceremony to ward off evil spirits, young men leap up to seize grass blades tied to a hazel tree.

Hikers on their way to the Hsiantien Hu.

A Saisiat tribesman ties a blade of grass round the arm of a tourist to ward off evil spirits.

Sharing a goblet of wine is the tribesmen's way of showing friendship.

All the aborigines who have settled down in the plains area must return to their homes to honor the dead. Even after dancing all night, they are not tired.

All the aborigines who have settled down in the plains area must return to their homes to honor the dead. Even after dancing all night, they are not tired.

All the aborigines who have settled down in the plains area must return to their homes to honor the dead. Even after dancing all night, they are not tired.

The spirit house has no tablets honoring the gods, and only serves as an activity center during the sacrificial ceremony.

A group of young men shoulders the gaudily decorated dance hat.

The bells on the hat also beat out the dance rhythm. In the ceremony to ward off evil spirits, young men leap up to seize grass blades tied to a hazel tree.