The large increase in expenditures for social welfare shows that the government is attaching ever greater importance to this area. Compared with Western countries, however, our social welfare expenditures are still rather limited. For example, the latest issue of The Economist indicates that social welfare expenditures in Britain make up 44 percent of the government's budget last year--and that's just for social insurance and the National Health Service, not including other items. So in terms of social welfare we're still a developing nation, even though economically we've advanced to the threshold of the developed countries.

Western countries that are developed in terms of social welfare have been facing difficulties, however. Britain is a prime example. After it became a welfare state in 1945, the government took on the responsibility of caring for the poor, the handicapped, the sick, and the unemployed from cradle to grave, but a deepening fiscal crisis forced the government to raise taxes during the 1960's.

As a result, the concept of social welfare is changing. The government can't take care of everything and everybody, so it demands that the individual look after himself first. This is called the "principle of individual responsibility."

Let's say the government came up with a new system in which, for instance, you could deduct your parents' medical expenses from your income tax if they lived with you, or you could deduct a certain percentage if there were a disabled person in the family. Would you want it? This is a new type of welfare service in which more money is left in the public's pockets, and individuals are encouraged to take on the responsibility of looking after themselves. Britain is now headed down this road.

When individuals have no way to look after themselves, the government steps in, spending the public's tax money. This is the second principle of social welfare, the principle of care and protection. In accordance with market principles, however, beneficiaries are still required to bear a portion of the cost, which is called "costsharing."

Whichever method is chosen, one principle is certain: no matter whether the government steps in directly and allocates social welfare resources, or whether it reaches the same result more indirectly, the main focus of social welfare service is disadvantaged groups, be they the elderly, the disabled, children, or the ailing. The people who need the most help are also the weakest members of society, unable to influence policy or fight for their rights. They carry no clout in the allocation of resources. So the government has to step in to help them.

Just how much of government expenses should be devoted to social welfare is a question of economics. Overtaxation has adversely affected the motivation for work and investment in many countries in Europe, where half of each day's earnings are paid in taxes. We probably don't want this kind of situation either. Raising taxes, in fact, is like plucking feathers from a goose: it hurts and squawks.

The government may find itself in something of a bind in the future. If it doesn't increase social welfare, it will be attacked. But if it tries to satisfy every need, a massive fiscal burden will result, and an increase in taxes would produce resentment. So social welfare is not simply a social question but also a political one.

There are only so many resources to go around, and more and more people asking for them. If contributions are not raised accordingly, the government will have to sacrifice quality. That is not a social welfare goal that we wish to pursue, I think.

[Picture Caption]

As the median age of the population rises, social welfare workers must plan for the advent of a "society of the aged." Shown here is a storytelling activity for the elderly held by the Taipei Department of Social Affairs. (photo by Vincent Chang)

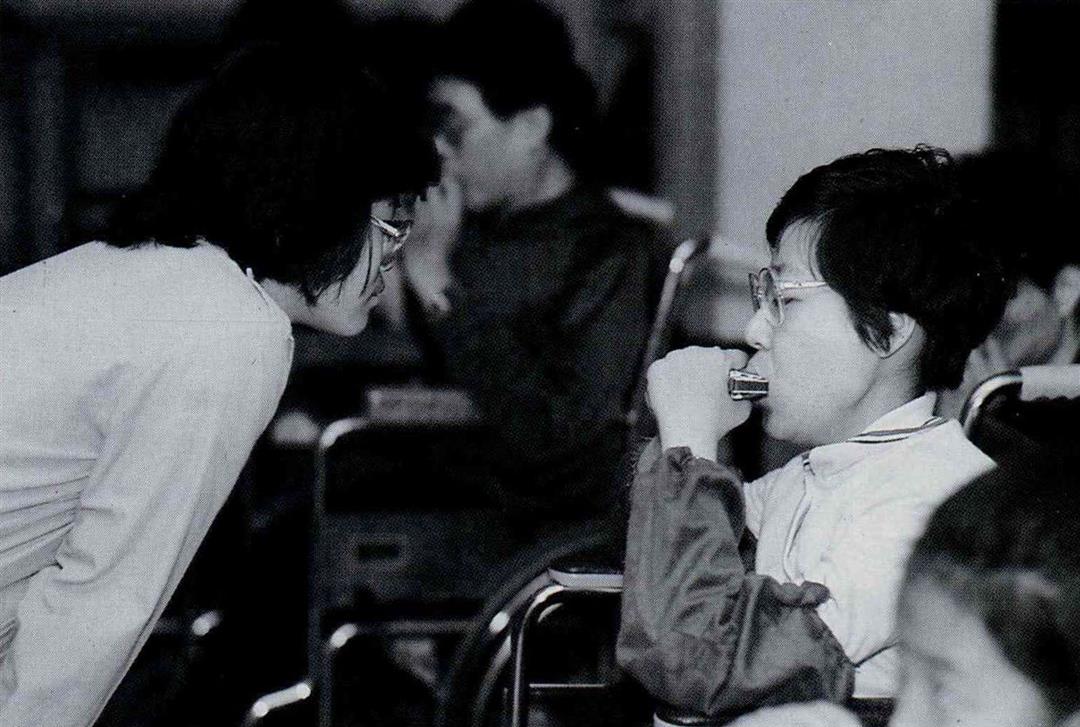

The government must step in to ensure the social welfare of the physically disabled, the mentally handicapped, and other disadvantaged persons. (photo from Sinorama files)

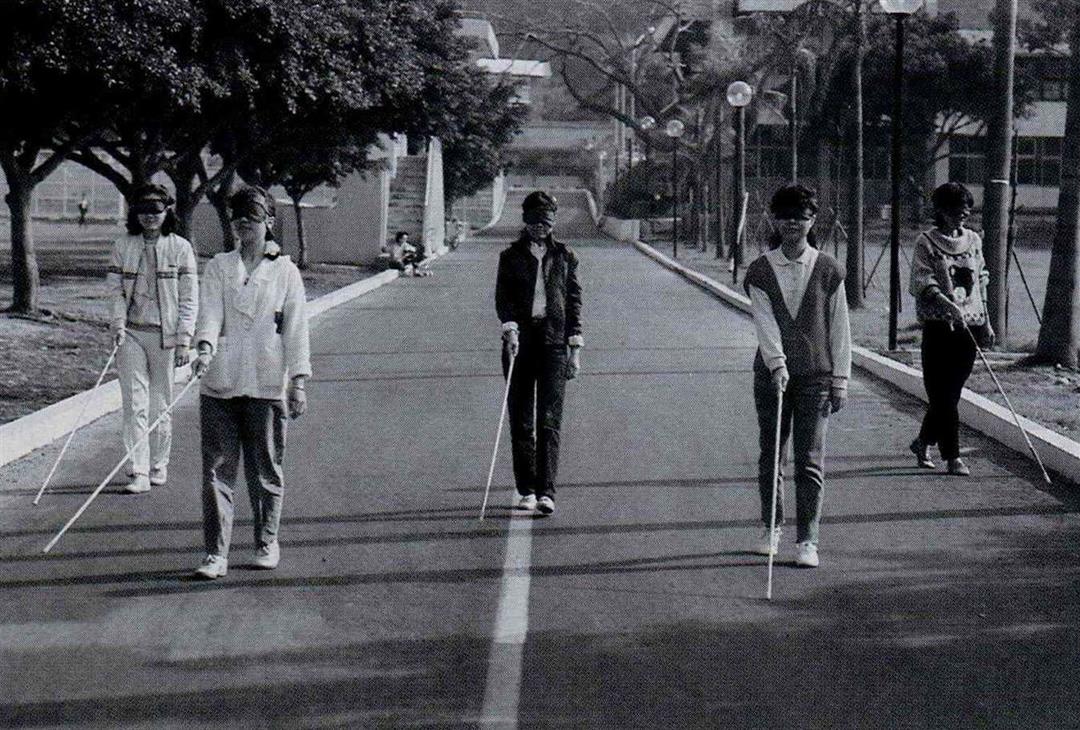

Students at National Taiwan College of Education imitate the blind in order to better under stand their needs and offer a more practical help. (photo from Sinorama files)

The government must step in to ensure the social welfare of the physically disabled, the mentally handicapped, and other disadvantaged persons. (photo from Sinorama files)

Students at National Taiwan College of Education imitate the blind in order to better under stand their needs and offer a more practical help. (photo from Sinorama files)